Haunted London, Index

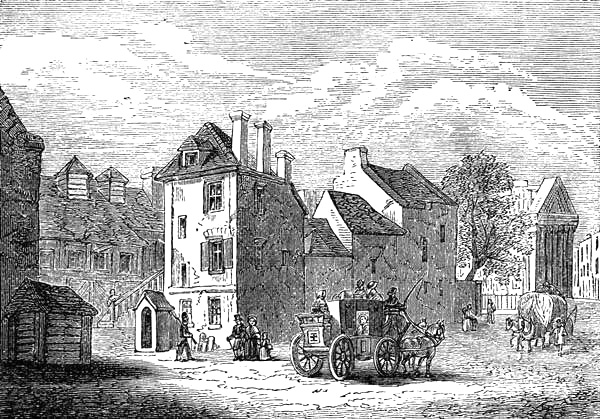

BARRACK AND OLD HOUSES ON SITE OF TRAFALGAR SQUARE, 1826.

CHAPTER X.

ST. MARTIN’S LANE.

Saint Martin’s Lane, extending from Long Acre to Charing Cross, was built before 1613, and then called the West Church Lane. The first church was built here by Henry VIII. The district was first called St. Martin’s Lane about 1617-18.[439]

Sir Theodore Mayerne, physician to James I., lived on the west side of this lane. Mayerne was the godson of Beza, the great Calvinist reformer, and one of Henry IV.’s physicians. He came to England after that king’s death. He then became James I.’s doctor, and was blamed for his[Pg 240] treatment of Prince Henry, whom many thought to have been poisoned. He was afterwards physician to Charles I., and nominally to Charles II.; but he died in 1655, five years before the Restoration. He gave his library to the College of Physicians, and is said to have disclosed some of his chemical secrets to the great enameller, Petitot.[440] Mayerne died of drinking bad wine at a Strand tavern, and foretold the time of his death.

A good story is told of Sir Theodore, which is the more curious because it records the fashionable fee of those days. A friend consulting Mayerne, and expecting to have the fee refused, ostentatiously placed on the table two gold broad pieces (value six-and-thirty shillings each). Looking rather mortified when Mayerne swept them into his pouch, “Sir.” said Sir Theodore, gravely, “I made my will this morning, and if it should become known that I refused a fee the same afternoon I might be deemed non compos.”[441]

Near this fortunate doctor, honoured by kings, lived Sir John Finett, a wit and a song-writer, of Italian extraction. He became Master of the Ceremonies to Charles I., and wrote a pedantic book on the treatment of ambassadors, and other questions of precedency, of the gravest importance to courtiers, but to no one else. He died in 1641.

Two doors from Mayerne and five from Finett, from 1622 to 1634, lived Daniel Mytens, the Dutch painter. On Vandyke’s arrival Mytens grew jealous and asked leave to return to the Hague. But the king persuaded him to stay, and he became friendly with his rival, who painted his portrait. There are pictures by this artist at Hampton Court. Prince Charles gave him his house in the lane for twelve years at the peppercorn rent of 6d. a year.

Next to Sir John Finett lived Sir Benjamin Rudyer, and on the same side Abraham Vanderoort, keeper of the pictures to Charles I., and necessarily an acquaintance of Mytens and Vandyke.

Carew Raleigh, son of the great enemy of Spain, and[Pg 241] born in the Tower, lived in this lane, on the west side, from 1636 to 1638, and again in 1664. This unfortunate man spent all his life in writing to vindicate his father’s memory, and in efforts to recover his Sherborne estate. In 1659, by the influence of General Monk, he was made Governor of Jersey.

The chivalrous wit, Sir John Suckling, dwelt in St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields in 1641, the year in which he joined in a rash plot to rescue Strafford from the Tower. He fled to France, and died there in poverty the same year, in the thirty-second year of his age. Suckling had served in the army of Gustavus Adolphus, and was famous for his sparkling repartee. There is an exquisite quaint grace about his poem of “The Wedding,” which has its scene at Charing Cross.

Dr. Thomas Willis, a great physician of his day, who died here in 1678, was grandfather of Browne Willis, the antiquary. Dr. Willis was a friend of Wren, and a great anatomist and chemist. He mapped out the nerves very industriously, and in his Cerebri Anatome forestalled many future phrenological discoveries.[442]

In the same year that eccentric charlatan, Sir Kenelm Digby, was living in the lane. The son of one of the gunpowder conspirators, and the “Mirandola” of his age, he was one of Ben Jonson’s adopted sons.[443] He was generous to the poets; he understood ten or twelve languages; he shattered the Venetian galleys at Scanderoon; he studied chemistry, and professed to cure wounds with sympathetic powder. He held offices of honour under Charles I., in France became a friend of Descartes, and after the Restoration was an active member of the Royal Society. He was born, won his naval victory, and died on the same day of the month. Ben Jonson, in a poem on him, calls him “prudent, valiant, just, and temperate,” and adds quaintly—

“His breast is a brave palace, a broad street,

Where all heroic ample thoughts do meet,

Where Nature such a large survey hath ta’en,

As others’ souls to his dwelt in a lane.”

[Pg 242]I cannot here help observing that the ridiculous story about Ben Jonson in his old age refusing money from Charles I., and rudely sending back word “that the king’s soul dwelt in a lane,” must have originated in some careless or malicious perversion of this line of the rough old poet’s.

“Immortal Ben” wrote ten poems on the death of Sir Kenelm’s wife, who was the daughter of Sir Edward Stanley, and, it is supposed, the mistress of the Earl of Dorset. Randolph, Habington, and Feltham also wrote elegies on this beautiful woman, who was found dead in her bed, accidentally poisoned, it is supposed, by viper wine, or some philtre or cosmetic given her by her experimentalising husband in order to heighten her beauty.[444] In one of Ben Jonson’s poems there are the following incomparable verses about Lady Venetia:—

“Draw first a cloud, all save her neck,

And out of that make day to break,

Till like her face it do appear,

And men may think all light rose there.”

And again—

“Not swelling like the ocean proud,

But stooping gently as a cloud,

As smooth as oil pour’d forth, and calm

As showers, and sweet as drops of balm.”

Sir Kenelm, when imprisoned in Winchester House, in Southwark, wrote an attack on Sir Thomas Browne’s sceptical work Religio Medici. He also produced a book on cookery, and a commentary on the Faerie Queen. This strange being was buried in Christ Church, Newgate Street.

St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields is an ancient parish, but it was first made independent of St. Margaret’s, Westminster, in 1535, by that tyrant Henry VIII., who, justly afraid of death, disliked the ceaseless black funeral processions of the outlying people of St. Martin’s passing the courtly gate of Whitehall, and who therefore erected a church near Charing[Pg 243] Cross, and constituted its neighbourhood into a parish.[445] In 1607, that unfortunate youth of promise, Henry Prince of Wales, added a chancel to the very small church, which soon proved insufficient for the growing and populous suburb. But though so modern, this parish formerly included in its vast circle St. Paul’s Covent Garden, St. James’s Piccadilly, St. Anne’s Soho, and St. George’s Hanover Square. It extended its princely circle as far north as Marylebone, as far south as Whitehall, as far east as the Savoy, and as far west as Chelsea and Kensington. When first rated to the poor in Queen Elizabeth’s time it contained less than a hundred rateable persons. The chief inhabitants lived by the river side or close to the church. Pall Mall and Piccadilly were then unnamed, and beyond the church westward were St. James’s Fields, Hay-hill Farm, Ebury Farm, and the Neat houses about Chelsea.[446]

In 1638 this overgrown parish, had carved out of it the district of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden; in 1684, St. James’s, Westminster; and in 1686, St. Anne’s, Soho. But even in 1680, Richard Baxter, with brave fervour, denounced what he called “the greatest cure in England,”[447] with its population of forty thousand more persons than the church could hold—people who “lived like Americans, without hearing a sermon for many years.” From such parishes of course crept forth Dissenters of all creeds and colours. In 1826 the churchyard was removed to Camden Town, and the street widened, pursuant to 7 George IV. c. 77.

That shrewd native of Aberdeen, Gibbs—a not unworthy successor of Wren—came to London at a fortunate time. Wren was fast dying; Vanbrugh was neglected; there was room for a new architect, and no fear of competition. His first church, St. Martin’s, was a great success. Though its steeple was heavy and misplaced, and the exterior flat and without light or shade,[448] the portico was foolishly compared[Pg 244] to that of the Parthenon, and was considered unique for dignity and unity of combination. The interior was so constructed as to render the introduction of further ornaments or of monuments impossible. Savage did but express the general opinion when he wrote with fine pathos—

“O Gibbs! whose art the solemn fanes can raise,

Where God delights to dwell and man to praise.”

The church was commenced in 1721 and finished in 1726, at a cost of £36,891: 10: 4, including £1500 for an organ.

With all its faults, it is certainly one of the finest buildings in London, next to St. Paul’s and the British Museum; but its cardinal fault is the unnatural union of the Gothic steeple and the Grecian portico. The one style is Pagan, the other Christian; the one expresses a sensuous contentment with this earth, the other mounts towards heaven with an eternal aspiration. The steeple leaps like a fountain from among lesser pinnacles that all point upwards. The Grecian portico is a cave of level shadow and of philosophic content.

St. Martin’s Church enshrines the dust of some illustrious persons. Here lies Nicholas Hilliard, the miniature-painter to Queen Elizabeth, and who died in 1619. He was a very careful painter, in the manner of Holbein. The great Isaac Oliver was his pupil. He must have had some trouble with the manly queen when she began to turn into a hag and to object to any shadow in her portraits. Near him, in 1621, was buried Paul Vansomer, a Flemish painter, celebrated for his portraits of James I. and his Danish queen. And here rests, too, a third and greater painter, William Dobson, Vandyke’s protégé, who, born in an unlucky age, and forgotten amid the tumult of the Civil War, died in 1646, in poverty, in his house in St. Martin’s Lane. Dobson had been apprenticed to a picture-dealer, and was discovered in his obscurity by Vandyke, whose style he imitated, giving it, however, a richer colour and more solidity. Charles I. and Prince Rupert both sat to him for their portraits. In this church reposes Sir Theodore Mayerne, an old court[Pg 245] physician. His conserve of bats and scrapings of human skulls could not keep him from the earthy bed it seems. Nicholas Stone, the sculptor, who died 1647, sleeps here (Stone’s son was Cibber’s master), all unknown to the learned Thomas Stanley, who died in 1678, and was known for his History of Philosophy and translation of Æschylus. Here, also, is John Lacey—first a dancing-master, afterwards a trooper, lastly a comedian. He died in 1681. Charles II. was a great admirer of Lacey, but unfortunately more so of Nell Gwynn, who also came to sleep here in 1687. Poor Nell! with her good-nature and simple frankness, she stands out, wanton and extravagant as she was, in pleasant contrast with the proud painted wantons of that infamous court.

If the dead could shudder, Secretary Coventry, who was buried here the year before Nell, must have shuddered at the neighbourhood in which he found himself; for he was the son of Lord Keeper Coventry, who died at Durham House in 1639-40. He had been Commissioner to the Treasury, and had given his name to Coventry Street. This great person became a precedent of burial to the Hon. Robert Boyle. This wise and good man, whom Swift ridiculed, was the inventor of the air-pump, and one of the great promoters of the Royal Society and of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. He died in 1691, and his funeral sermon was preached by Swift’s bête noir, that fussy time-server, Bishop Burnet.

In the churchyard lies a far inferior man, Sir John Birkenhead, who died in 1679. He was a great pamphlet-writer for the Royalists, and Lawes set some of his verses to music.[449] He left directions that he should not be buried within the church, as coffins were often removed. In or out of the church was buried Rose, Charles II.’s gardener, the first man to grow a pine-apple in England—a slice of which the king graciously handed to Mr. Evelyn.

Worst of all—a scoundrel, and fool among sensible men—here lies the bully and murderer, Lord Mohun, who fell in a duel in Hyde Park with the Duke of Hamilton, [Pg 246]immortalised in Mr. Thackeray’s Esmond. Mohun died in 1712. Here also, in 1721, came that vile and pretentious French painter, Louis Laguerre, whom Pope justly satirised. He was brought over by Verrio, and painted the “sprawling” “Labours of Hercules” at Hampton Court. He died of apoplexy at Drury Lane Theatre. That clever and determined burglar, Jack Sheppard, is said to have been buried in St. Martin’s in 1724. Farquhar, the Irish dramatist, author of “The Beaux’ Stratagem,” was interred here in 1707. Roubilliac, the French sculptor, who lived close by, was also buried in this spot, and Hogarth attended his funeral.

Mr. J. T. Smith, author of the Life of Nollekens, speaking of his own visits to the vaults of St. Martin’s Church, says, “It is a curious fact that Mrs. Rudd requested to be placed near the coffins of the Perreaus. Melancholy as my visits to this vault have been, I frankly own that pleasant recollections have almost invited me to sing, ‘Did you ne’er hear of a jolly young waterman?’ when passing by the coffin of my father’s old friend, Charles Bannister.”[450]

Mr. F. Buckland that delightful writer on natural history, who visited the same charnel-house in his search for the body of the great John Hunter, describes the vaults as piled with heaps of leaden coffins, horrible to every sense; but as I write from memory, I will not give the ghastly details.

That indefatigable and too restless exposer of abuses, Daniel Defoe, wrote a pamphlet in 1720 entitled “Parochial Tyranny; or, the Housekeeper’s Complaint against the Exactions of Select Vestries.” In this pamphlet he published one of the bills of the vestry of St. Martin’s in 1713, which contains the following impudent items:—

| “Spent at May meetings or visitation | £65 | 0 | 4 | |

| Ditto at taverns, with ministers, justices, overseers, &c. | 72 | 19 | 7 | |

| Sacrament bread and wine | 88 | 10 | 0 | |

| Paid towards a robbery | 21 | 14 | 0 | |

| Spent for dinner at the Mulberry Gardens | 49 | 13 | 4” |

[Pg 247]In 1818 the churchwardens’ dinner cost £56: 18s. Archdeacon Potts’ sermon on the death of Queen Charlotte not selling, the parish paid the loss, £48: 12: 9. In 1813 the vestry charged the parish £5 for petitioning against the Roman Catholics.

The Thames watermen have a plot set apart for themselves in St. Martin’s Churchyard. These amphibious and pugnacious beings were formerly notorious for their powers of sarcasm, though Dr. Johnson on a celebrated occasion put one of them out of countenance. In spite of coaches and sedan chairs—their horror in the times of the “Water Poet,” who must often have ferried Shakspere over to the Globe Theatre at the Bankside—they continued till the days of omnibuses and cheap cabs, rowing and singing, rejoicing in their scarlet tunics, and skimming to and fro over the Thames like swallows.

There is a Westminster tradition of a waterman who pretended to be deaf, and who was much employed by lovers, barristers who wished to air their eloquence, and young M.P.s who wanted to recite their speeches undisturbed.

In 1821 died Copper Holms, a well-known character on the river. He lived, with his wife and children, somewhere along the shore in an ark, which he had artfully framed from a West-country vessel, and which, coppers and all, cost him £150. The City brought an action to compel him to remove the obstruction. The honest fellow was buried in “The Waterman’s Churchyard,” on the south side of St. Martin’s Church.[451]

In 1683 Dr. Thomas Tenison, vicar of the parish, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury, lived in this street; he died at Lambeth in 1715. He founded in this parish a school and library. Though Swift did say he was “hot and heavy as a tailor’s iron,” he seems to have been one of the best and most tolerant of men, notwithstanding he attacked Hobbes and Bellarmine with his pen. He worked bravely during the plague, and was princely in his charities during the dreadful winter of 1683. It was he who prepared[Pg 248] Monmouth for death, and smoothed Queen Mary’s dying pillow. He was a steady friend of William of Orange.

Two doors from Slaughter’s, on the west side, but lower down, lived Ambrose Philips, from 1720 to 1724. Pope laughed at his “Pastorals,” which had been overpraised by Tickell. Though a friend of Addison and Steele, his sprightly but effeminate copies of verses procured him from Henry Carey the name of “Namby Pamby.” His “Winter Scene,” a sketch of a Danish winter, is, however, admirable.

Ambrose Philips was laughed at for advertising in the London Gazette, of January 1714, for contributions to a Poetical Miscellany. He was a Leicestershire man, and chiefly remarkable for translating Racine’s “Distressed Mother.” When the Whigs came into power under George I. he was put into the commission of the peace, and made a Commissioner of the Lottery. He afterwards became Registrar of the Prerogative Court at Dublin, wrote in the Free Thinker, and died in 1749. Pope laughed at the small poet as—

“The bard whom pilfered Pastorals renown,

Who turns a Persian tale for half-a-crown,

Just writes to make his barrenness appear,

And strains from hide-bound brains eight lines a year.”[452]

It was always one of Pope’s keenest strokes to call a man poor. Philips, in 1714, had industriously translated the Thousand and One Days, a series of Persian tales, and gained very honourably earned money. The wasp of Twickenham, whose malice never grew old, sketched Philips again as “Macer,” a simple, harmless fellow, who borrowed ends of verse, and whose highest ambition was “to wear red stockings and to dine with Steele.” Ambrose, naturally indignant to hear himself accused of stealing the little fame he had, very spiritedly hung up a birch at the bar of Button’s Coffee-house, with which he threatened to chastise the Æsop of the age if he dared show himself, but Pope wisely stayed at home.[453]

[Pg 249]The first house from the corner of Newport Street, on the right hand going to Charing Cross, was occupied by Beard, the celebrated public singer, who in 1738-9 married Lady Henrietta Herbert, the only daughter of the Earl Waldegrave. After her death the widower married the daughter of Mr. John Rich, the inventor of English pantomime, the best harlequin that probably ever lived, and the patentee of Covent Garden Theatre from 1732 to 1762. The parlour of the house had two windows facing the south towards Charing Cross. Here Mr. J. T. Smith describes his father smoking a pipe with Beard and George Lambert, the latter the founder of the Beef-steak Club and the clever scene-painter of Covent Garden Theatre. The fire of 1808 destroyed most of Lambert’s work with the theatre.[454]

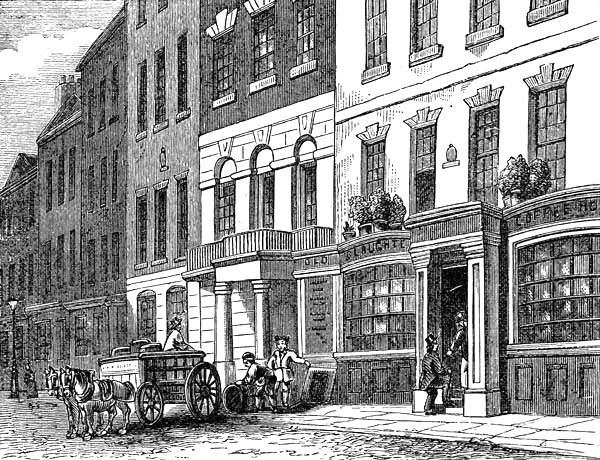

Next to this house stood “Old Slaughter’s” Coffee-house, the great haunt of artists from Hogarth to Wilkie. Towards the end of its existence it was the head-quarters of naval and military officers before the establishment of West End Clubs. It was pulled down in 1844 to make way for the new street between Long Acre and Leicester Square. The original landlord, John Slaughter, started it in 1692, and died about 1740.[455] It first became known as “Old Slaughter’s” in 1760, when an opposition set up in the street under the name of “Young” or “New Slaughter’s.”

There is a foolish tradition that the coffee-house derived its name from being frequented by the butchers of Newport Market. Mr. Smith gives a charming chapter on the frequenters of this old haunt of Dryden and afterwards of Pope. The first he mentions was Mr. Ware, the architect, who published a folio edition of Palladio, the great Italian architect of Elizabeth’s time. Ware was originally a chimney-sweeper’s boy in Charles Court, Strand; but being one day seen chalking houses on the front of Whitehall, a gentleman passing became his patron, educated him, and sent him to Italy. His bust was one of Roubilliac’s best works. His[Pg 250] skin is said to have retained the stain of soot to the day of his death.[456]

Gravelot, who kept a drawing-school in the Strand, nearly opposite Southampton Street, was another frequenter of Old Slaughter’s. Henri François Bourignon Gravelot was born in Paris in 1699, and died in that city in 1773. His drawings were always minutely finished, and his designs tasteful, particularly those which he etched himself for Sir John Hanmer’s small edition of Shakspere. He found an excellent engraver in poor Charles Grignon, Le Bas’ pupil, who in his old age was driven off the field, fell into poverty, and so remained till he died in 1810, aged 94.

John Gwynn, the architect, who lived in Little Court, Castle Street, Leicester Fields, also frequented this house. He built the bridge at Shrewsbury, and wrote a work on London improvements, which his friend Dr. Johnson revised and prefaced. The doctor also wrote strongly in favour of Gwynn’s talent and integrity when he was unsuccessfully competing with Mylne for the erection of old Blackfriars Bridge.

Hogarth, too, “used” Slaughter’s, and came there to rail at the “black old masters,” the follies of patrons, and the knavery of dealers. Here he would banter and brag, and sketch odd faces on his thumb-nail. Perhaps the “Midnight Conversation” was partly derived from convivial scenes in St. Martin’s Lane.

Roubilliac, the eccentric French sculptor, was another habitué of the place. His house and studio were opposite on the east side of the lane, and were approached by a long passage and gateway. Here his friends must have listened to his rhapsodies in broken English about his great statues of Handel, Sir Isaac Newton, and that of Shakspere now at the British Museum, which cost Garrick, who left it to the nation, three hundred guineas.[457]

That pompous and wretched portrait-painter, Hudson, Reynolds’s master and Richardson’s pupil, used also to frequent Slaughter’s. Hudson was the most ignorant of[Pg 251] painters, yet he was for a time the fashion. He painted the portraits of the members of the Dilettanti Society, and was a great and ignorant collector of Rembrandt etchings. Hogarth used to call him, in his brusque way, “a fat-headed fellow.”

Here Hogarth would meet his own engraver, M’Ardell, who lived in Henrietta Street. One of the finest English mezzotints in respect of brilliancy is Hogarth’s portrait of Captain Coram, the brave old originator of the Foundling Hospital, by M’Ardell. His engravings after Reynolds are superb. That painter himself said that they would immortalise him.[458]

Here, also, came Luke Sullivan, another of Hogarth’s engravers, from the White Bear, Piccadilly. His etching of “The March to Finchley” is considered exquisite.[459] Sullivan was also an exquisite miniature-painter, particularly of female heads. He was a handsome, lively, reckless fellow, and died in miserable poverty.

At Slaughter’s, too, Hogarth must have met the unhappy Theodore Gardelle, the miniature-painter, who afterwards murdered his landlady in the Haymarket and burnt her body. Hogarth is said to have sketched him in his ghostly white cap on the day of his execution. Gardelle, like Greenacre, pleaded that he killed the woman by an accidental blow, and then destroyed the body in fear. Foote notices his gibbet in The Mayor of Garratt.

Old Moser, keeper of the drawing academy in Peter’s Court—Roubilliac’s old rooms—was often to be seen at the same haunt. Moser was a German Swiss, a gold-chaser and enameller; he became keeper of the Royal Academy in 1768. His daughter painted flowers.

That great painter, poor old Richard Wilson, neglected and almost starved by the senseless art-patrons of his day, occasionally came to Slaughter’s, probably to meet his countryman, blind Parry, the Welsh harper and great draught-player.

And, last of all, we must mention Nathanael Smith, the[Pg 252] engraver, and Mr. Rawle, the accoutrement maker in the Strand, and the inseparable companion of Captain Grose, the great antiquary, on whom Burns wrote poems—a learned, fat, jovial Falstaff of a man, who compiled an indecorous but clever slang dictionary. It was at Rawle’s sale that Dickey Suett bought Charles II.’s black wig, which he wore for years in “Tom Thumb.”

Nos. 76 and 77 St. Martin’s Lane were originally one house, built by Payne, the architect of Salisbury Street and the original Lyceum. He built two small houses in his garden for his friends Gwynn, the competitor for Blackfriars Bridge, and Wale, the Royal Academy lecturer on perspective, and well-known book-illustrator. The entrances were in Little Court, Castle Street. In old times the street on this side, from Beard’s Court, to St. Martin’s Court, was called the Pavement; but the road has since been heightened three feet.

Below Payne’s, in Hogarth’s time, lived a bookseller named Harding, a seller of old prints, and author of a little book on the Monograms of Old Engravers. It was to this shop that Wilson, the sergeant painter, took an etching of his own, which was sold to Hudson as a genuine Rembrandt. That same night, by agreement, Wilson invited Hogarth and Hudson to supper. When the cold sirloin came in, Scott, the marine-painter, called out, “A sail, a sail!” for the beef was stuck with skewers bearing impressions of the new Rembrandt, of which Hudson was so proud.[460]

Nos. 88 and 89 were built on the site of a large mansion, the staircase of which was adorned with allegorical figures. It was here that Hogarth’s particular friend, John Pine, lived. Pine was the engraver and publisher of the scenes from the Armada tapestry in the House of Lords, now destroyed. He was a round, fat, oily man; and Hogarth drew him, much to his annoyance, as the fat friar eyeing the beef at the “Gate of Calais.” His son Robert, who painted one of the best portraits of Garrick, and carried off the hundred guinea prize of the Society of Arts for his picture of the[Pg 253] “Siege of Calais,” also lived here, and, after him, Dr. Gartshore.

The house No. 96, on the west side, was Powell the colourman’s in 1828; it had then a Queen Anne door-frame, with spread-eagle and carved foliage and flowers, like the houses in Carey Street and Great Ormond Street, and a shutter sliding in grooves in the old-fashioned way. Mr. Powell’s mother made for many years annually a pipe of wine from the produce of a vine nearly a hundred feet long.[461] This house had a large staircase, painted with figures in procession, by a French artist named Clermont, who claimed one thousand guineas for his work, and received five hundred. Behind the house was the room which Hogarth has painted in “Marriage à la Mode.” The quack is Dr. Misaubin, whose vile portrait the satirist has given. The savage fat woman is his Irish wife. Dr. Misaubin, who lived in this house, was the son of a pastor of the Spitalfields French Church. The quack realised a great fortune by a famous pill. His son was murdered; his grandson squandered his money, and died in St. Martin’s Workhouse.

No. 104 was at one time the residence of Sir James Thornhill, Hogarth’s august father-in-law, a poor yet pretentious painter, who decorated St. Paul’s. He painted the staircase wall with allegories that were existing some years since in good condition. The junior Van Nost, the sculptor, afterwards lived here—the same artist who took that mask of Garrick’s face which afterwards belonged to the elder Mathews. After him, before 1768, came Hogarth’s convivial artist-friend, Francis Hayman, who decorated Vauxhall and illustrated countless books. Perhaps it was here that the Marquis of Granby, before sitting to the painter, had a round or two of sparring. Sir Joshua Reynolds, too, a graver and colder man, came to live here before he went to Great Newport Street.

New Slaughter’s, at No. 82 in 1828, was established about 1760, and was demolished in 1843-44, when the new avenue of Garrick Street was made between Long Acre and[Pg 254] Leicester Square. It was much frequented by artists who wished cheap fare and good society. Roubilliac was often to be found here. Wilkie long after enjoyed his frugal dinners here at a small cost. He was always the last dropper-in, and was never seen to dine in the house before dark. The fact is, the patient young Scotchman always slaved at his art till the last glimpse of daylight had disappeared below the red roofs.

Upon the site of the present Quakers’ Meeting-house in St. Peter’s Court, St. Martin’s Lane, stood Roubilliac’s first studio after he left Cheere. Here he executed, with ecstatic raptures at his own genius, his great statue of Handel for Vauxhall. Here afterwards a drawing academy was started, Mr. Michael Moser being chosen the keeper. Reynolds, Mortimer, Nollekens, and M’Ardell were among the earliest members. Hogarth presented to it some of his father-in-law’s casts, but opposed the principle of cheap education to young artists, declaring that every foolish father would send his boy there to keep him out of the streets, and so the profession would be overstocked. In this academy the students sat to each other for drapery, and had also male and female models—sometimes in groups.

Amongst the early members of the St. Martin’s Lane Academy were the following:—Moser, afterwards keeper of the Academy; Hayman, Hogarth’s friend; Wale, the book-illustrator; Cipriani, famous for his book-prints; Allan Ramsay, Reynolds’s rival; F. M. Newton; Charles Catton, the prince of coach-painters; Zoffany, the dramatic portrait-painter; Collins, the sculptor, who modelled Hayman’s “Don Quixote;” Jeremy Meyer; William Woollett, the great engraver; Anthony Walker, also an engraver; Linnel, a carver in wood; John Mortimer, the Salvator Rosa of that day; Rubinstein, a drapery-painter and drudge to the portrait-painters; James Paine, son of the architect of the Lyceum; Tilly Kettle, who went to the East, painted several rajahs, and then died near Aleppo; William Pars, who was sent to Greece by the Dilettanti Society; Vandergutch, a painter who turned picture-dealer; Charles Grignon, the[Pg 255] engraver; C. Norton, Charles Sherlock, and Charles Bibb, also engravers; Richmond, Keeble, Evans, Roper, Parsons, and Black, now forgotten; Russell, the crayon-painter; Richmond Cosway, the miniature-painter, a fop and a mystic; W. Marlowe, a landscape-painter; Messrs. Griggs, Rowe, Dubourg, Taylor, Dance, and Ratcliffe, pupils of gay Frank Hayman; Richard Earlom, engraver of the “Liber Veritatis” of Claude for the Duke of Richmond; J. A. Gresse, a fat artist who taught the queen and princesses drawing; Giuseppe Marchi, an assistant of Reynolds; Thomas Beech; Lambert, a sculptor, and pupil of Roubilliac; Reed, another pupil of the same great artist, who aided in executing the skeleton on Mrs. Nightingale’s monument, and was famous for his pancake clouds; Biaggio Rebecca, the decorator; Richard Wilson, the great landscape-painter; Terry, Lewis Lattifere, John Seton, David Martin, Burgess; Burch, the medallist; John Collett, an imitator of Hogarth; Nollekens, the sculptor; Reynolds, and, of course, Hogarth himself, the primum mobile.[462]

No. 112 was in old times one of those apothecaries’ shops with bottled snakes in the windows. It was kept by Leake, the inventor of a “diet-drink” once as famous as Lockyer’s pill.

Frank Hayman, one of these St. Martin’s Lane worthies, was originally a scene-painter at Drury Lane. He was with Hogarth at Moll King’s when Hogarth drew the girl squirting brandy at the other for his picture in the Rake’s Progress. Hayman was a Devonshire man, and a pupil of Brown. When he buried his wife, a friend asked him why he spent so much money on the funeral. “Oh, sir,” replied the droll, revelling fellow, “she would have done as much or more for me with pleasure.”

Quin and Hayman were inseparable boon companions. One night, after “beating the rounds,” they both fell into the kennel. Presently Hayman, sprawling out his shambling[Pg 256] legs, kicked his bedfellow Quin. “Hallo! what are you at now?” growled the Welsh actor. “At? why, endeavouring to get up, to be sure, for this don’t suit my palate.” “Pooh!” replied Quin, “remain where you are; the watchman will come by shortly, and he will take us both up!”[463]

No. 113 was occupied by Thomas Major, a die-engraver to the Stamp Office, a pupil of Le Bas, and an excellent reproducer of subjects from Teniers. He was also an engraver of landscapes after pictures by Ferg, one of the artists employed with Sir James Thornhill at the Chelsea china manufactory.

The old watch-house or round-house used to stand exactly opposite the centre of the portico of Gibbs’s church.[464] There is a rare etching which represents its front during a riot. Stocks, elaborately carved with vigorous figures of a man being whipped by the hangman, stood near the wall of the watch-house. The carving, much mutilated, was preserved in the vaults under the church.

Near the stocks, with an entrance from the King’s Mews, stood “the Barn,” afterwards called “the Canteen,” which was a great resort of the chess, draught, and whist players of the City.

At the south-west corner of St. Martin’s Lane was the shop of Jefferys, the geographer to King George III.

No. 20 was a public-house, latterly the Portobello, with Admiral Vernon’s ship, well painted by Monamy, for its sign. The date, 1638, was on the front of this house, now removed.

No. 114 stands on the site of the old house of the Earls of Salisbury. Before the alterations of 1827 there were vestiges of the old building remaining. It has been a constant tradition in the lane, that in this house, in James II.’s reign, the seven bishops were lodged before they were conveyed to the Tower.

Opposite old Salisbury House stood a turnpike, and the tradition in the lane is that the Earl of Salisbury obtained its removal as a nuisance. At that time the church was[Pg 257] literally in the fields. The turnpike-house stood (circa 1760) on the site of No. 28, afterwards (in 1828) Pullen’s wine-vaults. The Westminster Fire Office was first established in St. Martin’s Lane, between Chandos Street and May’s Buildings.

The White Horse livery-stables were originally tea-gardens,[465] and south of these was a hop-garden. The oldest house in the lane overhung the White Horse stables, and was standing in 1828.

No. 60 was formerly Chippendale’s, the great upholsterer and cabinet-maker, whose folio work was the great authority in the trade before Mr. Hope’s classic style overthrew for a time that of Louis Quatorze.

No. 63 formerly led to Roubilliac’s studio. Here, in 1828, the Sunday paper The Watchman, was printed.

It must have been here, in the sculptor’s time, that Garrick, coming to see how his Shakspere statue progressed, drew out a two-foot rule, and put on a tragic and threatening face to frighten a great red-headed Yorkshireman, who was sawing marble for Roubilliac; but who, to his surprise, merely rolled his quid, and coolly said, “What trick are you after next, my little master?” Upon the honest sculptor’s death, Read, one of his pupils, a conceited pretender, took the premises in 1762, and advertised himself as “Mr. Roubilliac’s successor.”

Read executed the poor monuments of the Duchess of Northumberland and of Admiral Tyrrell, now in Westminster Abbey. His master used to say to Read when he was bragging, “Ven you do de monument, den de varld vill see vot von d— ting you vill make.” Nollekens used to say of the admiral’s monument, “That figure going to heaven out of the sea looks for all the world as if it were hanging from a gallows with a rope round its neck.”[466]

No. 70 was formerly the house where Mr. Hone held his exhibition when his picture of “The Conjuror,” intended to ridicule Sir Joshua Reynolds as a plagiarist, and to insult Miss Angelica Kaufmann, was refused admittance at Somerset[Pg 258] House. Mr. Nathanael Hone was a miniature-painter on enamel, who attempted oil pictures and grew envious of Reynolds. Hone was a tall, pompous, big, erect man, who wore a broad brimmed hat and a lapelled coat, punctiliously buttoned up to his chin. He walked with a measured, stately step, and spoke with an air of great self-importance—in this sort of way: “Joseph Nollekens, Esq., R.A., how—do—you—do?”[467]

The corner house of Long Acre, now 72, formed part of the extensive premises of Mr. Cobb, George III.’s upholsterer—a proud, pompous man, who always strutted about his workshops in full dress. It was Dance’s portrait of Mr. Cobb, given in exchange for a table, that led to Dance’s acquaintance with Garrick. One day in the library at Buckingham House, old King George asked Cobb to hand him a certain book. Instead of doing so, mistaken Cobb called to a man who was at work on a ladder, and said, “Fellow, give me that book.” The king instantly rose and asked the man’s name. “Jenkins,” replied the astonished upholsterer. “Then,” observed the good old king, “Jenkins shall hand me the book.”[468]

Alderman Boydell, the great encourager of art, when he first began with half a shop, used to etch small plates of landscapes in sets of six for sixpence. As there were few print-shops then in London, he prevailed upon the proprietors of toy-shops to put them in their windows for sale. Every Saturday he went the round of the shops to see what had been done, or to take more. His most successful shop was “The Cricket-Bat,” in Duke’s Court, St. Martin’s Lane.[469]

Abraham Raimbach, the engraver, was born in Cecil Court, St. Martin’s Lane, in 1776. Sir Joshua Reynolds, in his early period, lived nearly opposite May’s Buildings. He afterwards went to Great Newport Street, where he first met Dr. Johnson.

O’Keefe describes being in a coffee-house in St. Martin’s Lane on the very morning when the famous No. 45 came[Pg 259] out. The unconscious newsman came in, and, as a matter of course, laid the paper on the table before him. About the year 1777 O’Keefe was standing talking with his brother at Charing Cross, when a slender figure in a scarlet coat with a large bag, and fierce three-cocked hat, crossed the way, carefully choosing his steps, the weather being wet—it was John Wilkes.[470]

When Fuseli returned to London in 1779, after his foreign tour, he resided with a portrait painter named Cartwright, at No. 100 St. Martin’s Lane,[471] and he remained there till his marriage with Miss Rawlins in 1788, when he removed to Foley Street. Here he commenced his acquaintance with Professor Bonnycastle, and produced his popular picture of “The Nightmare” (1781), by which the publisher of the print realised £500. Here also he revised Cowper’s version of the Iliad, and became acquainted with Sir Joshua Reynolds and Dr. Moore, the author of Zeluco.

May’s Buildings bear the date of 1739. Mr. May, who built them, lived at No. 43, which he ornamented with pilasters and a cornice. This house used to be thought a good specimen of architectural brickwork.

The club of “The Eccentrics,” in May’s Buildings, was, in 1812, much frequented by the eloquent Richard Lalor Sheil, by William Mudford, the editor of the Courier, a man of logical and sarcastic power,—and by “Pope Davis,” an artist, in later years a great friend of the unfortunate Haydon. “Pope Davis” was so called from having painted, when in Rome, a large picture of the “Presentation of the Shrewsbury Family to the Pope.”[472]

The Royal Society of Literature, at 4 St. Martin’s Place, Charing Cross, was founded in 1823, “for the advancement of literature,” on which at present it has certainly had no very perceptible influence. It was incorporated by royal charter Sept. 13, 1826. George IV. gave 1000 guineas a[Pg 260] year to this body, which rescued the last years of Coleridge’s wasted life from utter dependence, and placed Dr. Jamieson above want. William IV. discontinued the lavish grant of a king who was generous only with other people’s money, and was always in debt; and since that the somewhat effete society has sunk into a Transaction Publishing Society, or rather a club with an improving library. Sir Walter Scott’s opposition to the society was as determined as Hogarth’s against the Royal Academy. “The immediate and direct favour of the sovereign,” said Scott, who had a superstitious respect for any monarch, “is worth the patronage of ten thousand societies.” Literature wants no patronage now, thank God, but only intelligent purchasers; and whether a king does or does not read an author’s work, is of small consequence to any writer.

OLD SLAUGHTER’S COFFEE-HOUSE.

[Pg 261]Admission to the Royal Society of Literature is obtained by a certificate, signed by three members, and an election by ballot. Ordinary members pay three guineas on admission, and two guineas annually, or compound by a payment of twenty guineas. The society devotes itself for the most part to the study of Greek and Latin inscriptions and Egyptian literature.[473] This learned body also professes to fix the standard of the English language; to read papers on history, poetry, philosophy, and philology; to correspond with learned men in foreign countries; to reward literary merit; and to publish unedited remains of ancient literature.

St. Martin’s Lane has seen many changes. Cranbourne Alley is gone with all its bonnet-shops, and the Mews and C’ribbee Islands are no more, but there still remain a few old houses, with brick pilasters and semi-Grecian pediments, to remind us of the days of Fuseli and Reynolds, Hayman and Old Slaughter’s, Hogarth and Roubilliac. I can assure my readers that a most respectable class of ghosts haunts the artist quarter in St. Martin’s Lane.

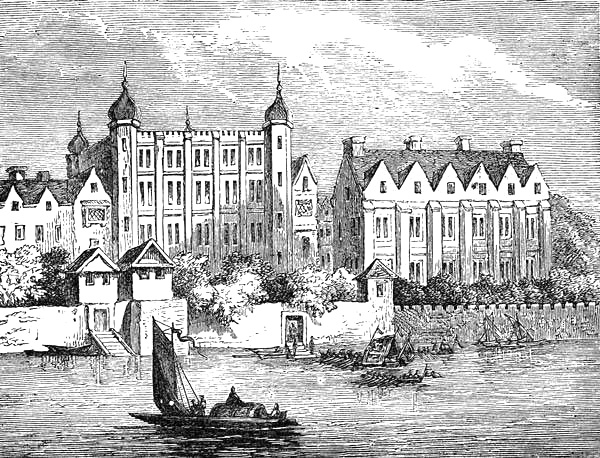

SALISBURY AND WORCESTER HOUSES, 1630.

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:12:52 GMT