Haunted London, Index

CHAPTER XI.

LONG ACRE AND ITS TRIBUTARIES.

At the latter end of 1664, says Defoe, two men, said to be Frenchmen, died of the plague at the Drury Lane end of Long Acre. Dr. Hodges, however, a greater authority than Defoe, who wrote fifty-seven years after the event, says merely that the pestilence broke out in Westminster, and that two or three persons dying, the frightened neighbours removed into the City, and there carried the contagion. He, however, distinctly states that the pest came to us from[Pg 263] Holland, and most probably in a parcel of infected goods from Smyrna.[474]

According to Defoe, the family with which the Frenchmen had lodged endeavoured to conceal the deaths; but the rumour growing, the Secretary of State heard of it, and sent two physicians and a surgeon to inspect the bodies. They certifying that the men had really died of the plague, the parish clerk returned the deaths to “the Hall,” and they were printed in the weekly bill of mortality. “The people showed a great concern at this, and began to be alarmed all over the town.”[475] At Christmas Dr. Hodges attended a case of plague, and shortly afterwards a proclamation was issued for placing watchmen day and night at the doors of infected houses, which were to be marked with a red St. Andrew cross and the subscription “Lord have mercy upon us!”[476] By the next September the terrible disease had risen to its height, and the deaths ranged as high as 12,000 a week, and in the worst night after the bonfires had been burned in the street, to 4000 in the twelve hours.[477]

Great Queen Street, so called after Henrietta Maria, the imprudent but brave wife of Charles I., was built about 1629, before the troubles. Howes (editor of Stow) speaks in 1631, of “the new fair buildings leading into Drury Lane.”[478] Many of the houses were built by Webb, one of Inigo Jones’s scholars. The south was the fashionable side, looking towards the Pancras fields; most of the north side houses must, therefore, be of a later date. According to one authority Inigo Jones himself built Queen Street, at the cost of the Jesuits, designing it for a square, and leaving in the middle a niche for the statue of Queen Henrietta. “The stately and magnificent houses,” begun on the other side near Little Queen Street, were not continued. There were fleurs-de-luce placed on the walls in honour of the queen.[479]

[Pg 264]George Digby, the second Earl of Bristol, lived in Great Queen Street, in a large house with seven rooms on a floor, a long gallery, and gardens. Evelyn describes going to see him (probably there), to consult about the site of Greenwich Hospital, with Denham the poet and surveyor, and one of Inigo Jones’s clerks. Digby was a Knight of the Garter, who first wrote against Popery and then converted himself. He persecuted Lord Strafford, yet then turning courtier, lived long enough to persecute Lord Clarendon. Grammont, Bussy, and Clarendon all decry the earl; and Horace Walpole writes wittily of him—“With great parts, he always hurt himself and his friends; with romantic bravery, he was always an unsuccessful commander. He spoke for the Test Act, though a Roman Catholic, and addicted himself to astrology on the birthday of true philosophy.”[480]

In 1671 Evelyn describes the earl’s house as taken by the Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, of which he was one, and furnished with tapestry “of the king’s.” The Duke of Buckingham, the earl of Sandwich (Pepys’s patron), the Earl of Lauderdale, Sir John Finch, Waller the poet, and saturnine Colonel Titus (the author of the terrible pamphlet against Cromwell, Killing no Murder) were the new occupants.

They sat, says Evelyn, at the board in the council chamber, a very large room furnished with atlases, maps, charts, and globes. The first day’s debate was an ominous one: it related to the condition of New England, which had grown rich, strong, and “very independent as to their regard to Old England or his majesty. The colony was able to contest with all the other plantations,[481] and there was fear of her breaking from her dependence. Some of the council were for sending a menacing letter, but others who better understood the peevish and touchy humour of that colony were utterly against it.” A few weeks afterwards Evelyn was at the council, when a letter was read from Jamaica, describing how Morgan, the Welsh buccaneer,[Pg 265] had sacked and burned Panama; the bravest thing of the kind done since Drake. Morgan, who cheated his companions and stole their spoil, afterwards came to England, and was, like detestable Blood, received at court.

Lord Chancellor Finch, Earl of Nottingham, who lived in Great Queen Street, presided as Lord High Steward at Lord Strafford’s trial, at which Evelyn was present, noticing the ill-bred impudence of Titus Oates.[482] Finch was the son of a recorder of London, and died in 1681. He was living here when that impudent thief, Sadler, stole the mace and purse, and carried them off in procession.

The choleric and Quixotic Lord Herbert of Cherbury lived in Great Queen Street, in a house on the south side, a few doors east of Great Wyld Street. Here he began his wild Deistic work, De Veritate, published in Paris in 1624, and in London three years before his death. He says that he finished this rhapsody in France, where it was praised by Tilenus, an Arminian professor at Sedan, and an opponent of the Calvinists, which procured him a pension from James I., and also from the learned Grotius when he came to Paris, after his escape in a linen-chest from the Calvinist fortress of Louvestein. Urged to publish by friends, Lord Herbert, afraid of the censure his book might receive, was relieved from his doubts by what his vanity and heated imagination pleased to consider a vision from heaven.

This Welsh Quixote says, “Being thus doubtful in my chamber one fair day in the summer, my casement being open towards the south, the sun shining clear and no wind stirring, I took my book, De Veritate, in my hand, and kneeling on my knees, devoutly said these words: ‘Oh, thou eternal God, author of the light which now shines upon me, and giver of all inward illuminations, I do beseech thee of thy infinite goodness to pardon a greater request than a sinner ought to make. I am not satisfied enough whether I shall publish this book, De Veritate. If it be for thy glory, I beseech thee to give me some sign from heaven; if not, I[Pg 266] shall suppress it!’ I had no sooner spoken these words, but a loud though gentle noise[483] came from the heavens (for it was like nothing on earth), which did so comfort and cheer me that I took my petition as granted. And this (however strange it may seem) I protest before the eternal God is true. Neither am I in any way superstitiously deceived herein, since I did not only hear the noise, but in the serenest sky that ever I saw—being without all cloud—did, to my thinking, see the place from whence it came.”

The noise was probably some child falling from a chair overhead, or a chest of drawers being moved in an upper room; and if it had been thunder in a clear sky, it was no more than Horace once heard. Heaven does not often express its approval of Deistical books. Lord Herbert, doubted of general, and yet believed in individual revelation. What crazy vanity, to think the work of an amateur philosopher of sufficient importance for a special revelation,[484] that (in his own opinion) had been denied to a neglected world! Lord Herbert, though refused the sacrament by Usher, bore it very serenely, asked what o’clock it was, then said, “An hour hence I shall depart,” turned his head to the other side, and expired.[485] He had moved to this quarter from King Street. Lord Herbert, though he wrote a Life to vindicate that brutal tyrant Henry VIII., was inconsistent enough to join the Parliament against a less wise but more illegal king, Charles I. When I pass down Queen Street, wondering whether that southern window of the Welsh knight’s vision was on the front of the south side, or on the back of the southern side of the street, I sometimes think of those soft lines of his upon the question “whether love should continue for ever?”

“Having interr’d her infant birth,

The watery ground that late did mourn

Was strew’d with flowers for the return

Of the wish’d bridegroom of the earth.

[Pg 267]

“The well-accorded birds did sing

Their hymns unto the pleasant time,

And in a sweet consorted chime,

Did welcome in the cheerful spring.”

And then on my return home, I get out brave old Ben Jonson, and read his lines addressed to this last of the knights:—

“... and on whose every part

Truth might spend all her voice, Fame all her art.

Whether thy learning they would take, or wit,

Or valour, or thy judgment seasoning it,

Thy standing upright to thyself, thy ends

Like straight, thy piety to God and friends.”

Sir Thomas Fairfax, general of the Parliament, probably lived here, as he dated from this street a printed proclamation of the 12th of February 1648.

Sir Godfrey Kneller, the great portrait painter of William and Mary’s reign, but more especially of Queen Anne’s time, once lived in a house in this street. Sir Godfrey, though a humorist, was the vainest of men, and was made rather a butt by his friends Pope and Gay. Kneller was the son of a surveyor at Lübeck, and intended for the army. King George I., who created him a baronet, was the last of the sovereigns who sat to him. Sir Godfrey was the successor of Sir Peter Lely in England, but was still more slight and careless in manner. His portraits may be often known by the curls being thrown behind the back, while in Lely’s portraits they fall over the shoulders and chest. Kneller was a humorist, but very vain, as a man might well be whom Dryden, Pope, Addison, Prior, Tickell, and Steele had eulogised in verse. On one occasion, when Pope was sitting watching Kneller paint, he determined to fool him “to the top of his bent.” “Do you not think, Sir Godfrey,” said the little poet, slily, “that, if God had had your advice at the creation, he would have made a much better world?” The painter turned round sharply from his easel, fixed his eyes on Pope, and laying one hand on his deformed shoulder, replied, “Fore Gott, Mister Pope, I theenk I shoode.”

[Pg 268]There was wit in all Kneller’s banter, and even when his quaint sayings told against himself, they seemed to reflect the humour of a man conscious of the ludicrous side of his own vanity. To his tailor who brought him his son to offer him as an apprentice emulative of Annibale Caracci, whose father had also sat cross-legged, Sir Godfrey said, grandly, “Dost thou think, man, I can make thy son a painter? No; God Almighty only makes painters.” To a low fellow whom he overheard cursing himself he said, “God damn you? No, God may damn the Duke of Marlborough, and perhaps Sir Godfrey Kneller; but do you think he will take the trouble of damning such a scoundrel as you?”[486]

Gay on one occasion read some verses to Sir Godfrey (probably those describing Pope’s imaginary welcome from Greece) in which these outrageous lines occur—

“What can the extent of his vast soul confine—

A painter, critic, engineer, divine?”

Upon which Kneller, remembering that he had been intended for a soldier, and perhaps scenting out the joke, said, “Ay, Mr. Gay, all vot you ’ave said is very faine and very true, but you ’ave forgot von theeng, my good friend. Egad, I should have been a general of an army, for ven I vos in Venice there vos a girandole, and all the Place of St. Mark vos in a smoke of gunpowder, and I did like the smell, Mr. Gay—should have been a great general, Mr. Gay.”[487]

His dream, too, was related by Pope to Spence as a good story of the German’s droll vanity. Kneller thought he had ascended by a very high hill to heaven, and there found St. Peter at the gate, dealing with a vast crowd of applicants. To one he said, “Of what sect was you?” “I was a Papist.” “Go you there.” “What was you?” “A Protestant.” “Go you there.” “And you?” “A Turk.” “Go you there.” In the meantime St. Luke had descried the painter, and asking if he was not the famous Sir Godfrey Kneller, entered into conversation with[Pg 269] him about his beloved art, so that Sir Godfrey quite forgot about St. Peter till he heard a voice behind him—St. Peter’s—call out, “Come in, Sir Godfrey, and take whatever place you like.”[488]

Pope is said to have ridiculed his friend under the name of Helluo.[489] He certainly laughed at his justice in dismissing a soldier who had stolen a joint of meat, and blaming the butcher who had put it in the rogue’s way. Whenever he saw a constable, followed by a mob, coming up to his house at Whitton, he would call out to him, “Mr. Constable, you see that turning; go that way; you will find an ale-house, the sign of the King’s Head: go and make it up.”[490]

Jacob Tonson got pictures out of Kneller, covetous as he was, by praising him extravagantly, and sending him haunches of fat venison and dozens of cool claret. Sir Godfrey used to say to Vandergucht, “Oh, my goot man, this old Jacob loves me. He is a very goot man, for you see he loves me, he sends me goot things. The venison vos fat.” Old Geckie, the surgeon, however, got a picture or two even cheaper, for he sent no present, but then his praises were as fat as Jacob’s venison.[491]

Sir Godfrey used to get very angry if any doubt was expressed as to the legitimacy of the Pretender. “His father and mother have sat to me about thirty-six times a-piece, and I know every line and bit of their faces. Mine Gott, I could paint King James now by memory. I say the child is so like both, that there is not a feature in his face but what belongs to either father or mother—nay, the nails of his fingers are his mother’s—the queen that was. Doctor, you may be out in your letters, but I cannot be out in my lines.”[492]

Kneller had intended Hogarth’s father-in-law, Sir James Thornhill, to paint his staircase at Whitton, but hearing that Newton was sitting to him, he was in dudgeon, declared[Pg 270] that no portrait-painter should paint his house, and employed “sprawling” Laguerre instead.

Kneller’s prices were fifteen guineas for a head, twenty if with only one hand, thirty for a half, and sixty for a whole length. He painted much too fast and flimsily, and far too much by the help of foreign assistants—in fact, avowedly to fill his kitchen. In thirty years he made a large fortune, in spite of losing £20,000 in the South Sea Bubble. His wigs, drapery, and backgrounds were all painted for him. He is said to have left at his death 500 unfinished portraits.[493] His favourite work, the portrait of a Chinese converted and brought over by Couplet, a Jesuit, is at Windsor. But Walpole preferred his Grinling Gibbons at Houghton.

Kneller left his house in Great Queen Street to his wife, and after her decease to his godson Godfrey Huckle, who took the name of Kneller. Amongst the celebrated persons painted by Kneller in his best manner were Bolingbroke, Wren, Lady Wortley Montague, Pope, Locke, Burnet, Addison, Evelyn, and the Earl of Peterborough. The brittleness of this man’s fame is another proof that he who paints merely for his time must perish with his time.

Conway House was in Great Queen Street. Lord Conway, an able soldier, brought up by Lord Vere, his uncle, was an epicure, who by his agreeable conversation was very acceptable at the court of Charles I.[494] He had the misfortune to be utterly routed by the Scotch at Newburn—a defeat which gave them Newcastle. The previous Lord Conway was that Secretary of State of whom James I. said, “Steenie has given me two proper servants—a secretary (Conway) who can neither write nor read, and a groom of the bedchamber (Mr. Clarke, a one-handed man) who cannot truss my points.”[495] It had been well for England if this sottish pedant had had no worse servants than Conway and Clarke. Raleigh might then have been spared, and Overbuy would not have been poisoned.

Lord Conway, whose son, General Conway, was such an[Pg 271] idol of Horace Walpole, lived in the family house in Great Queen Street.

Winchester House was not far off. Lord Pawlet figures in all the early scenes of the Civil War. He was one of the first nobles to raise forces in the West for the wrong-headed king. On one occasion Basing House was all but lost by a plot hatched between Waller and the Marquis of Winchester’s brother, but it was detected in time to save that important place. Basing, after three months’ siege by a conjunction of Parliament troops from Hampshire and Essex, was gallantly succoured by Colonel Gage. The Marchioness, a lady of great honour and alliance, being sister to the Earl of Essex and to the lady Marchioness of Hertford, enlisted all the Roman Catholics in Oxford in this dashing adventure.[496] Basing was, however, eventually stormed and taken by Cromwell, who put most of the garrison to the sword. William, the fourth marquis, died 1628, and was succeeded by his son, who was the father of Charles, created in 1689 Duke of Bolton, a title that became extinct in 1794.

John Greenhill, a Long Acre celebrity, was one of the most promising of Lely’s scholars. He painted portraits, among others, of Locke, Shaftesbury, and Davenant. He also drew in crayons, and engraved. It is said that Lely was jealous of him, and would not let his pupil see him paint, till Greenhill’s handsome wife was sent to Sir Peter to sit for her portrait, which cost twelve broad pieces or £15. Greenhill, at first industrious, became acquainted with the players, and fell into debauched courses. Coming home drunk late one night from the Vine Tavern, he fell into the kennel in Long Acre, and was carried to Perrey Walton’s, the royal picture-cleaner, in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where he had been lodging, and died in his bed that night (1676), in the flower of his age. He was buried at St. Giles’s, and shameless Mrs. Aphra Behn, who admired his person and his paintings, wrote a long elegy on his death. Sir Peter is said to have settled £40 a year on Greenhill’s widow and children, but she died mad soon after her husband.[497]

[Pg 272]In June 1718 Ryan, an actor of Lincoln’s Inn Theatre, was supping at the Sun in Long Acre, and had placed his sword quietly in the window, when a bully named Kelly came up and made passes at him, provoking him to a duel. The young actor took his sword, drew it, and passed it through the rascal’s body. The act being one of obvious self-defence, he was not called to serious account for it. This Ryan had acted with Betterton. Addison especially selected him as Marcus in his “Cato,” and Garrick confessed he took Ryan’s Richard as his model.[498]

Some years after, Ryan, by this time the Orestes, Macduff, Iago, Cassio, and Captain Plume of the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre, in passing down Great Queen Street, after playing Scipio in “Sophonisba,” was fired at by a footpad, and had his jaw shattered. “Friend,” moaned the wounded man, “you have killed me, but I forgive you.” The actor, however, recovered to resume his place upon the boards, and generous Quin gave him £1000 in advance that he had put him down for in his will. He died in 1760.

Hudson, a wretched portrait-painter, although the master of Sir Joshua Reynolds, lived in a house now divided into two, Nos. 55 and 56. Portrait-painting, being unable to sink lower than Hudson, turned and began to rise again. When Reynolds in later years took a villa on Richmond Hill, somewhat above that of Hudson, he said, “I never thought I should live to look down on my old master.” Hudson’s house was afterwards occupied by that insipid poet, Hoole, the translator of Tasso and of Ariosto.

The old West End entrance of this street, a narrow passage known as the “Devil’s Gap,” was taken down in 1765.

Martin Folkes, an eminent scholar and antiquarian, was born in Great Queen Street in 1690. He was made vice-president of the Royal Society by Newton in 1723, and in 1727, on Sir Isaac’s death, disputed the presidentship with Sir Hans Sloane,—a post which he eventually obtained in 1741, on the resignation of Sir Hans. Folkes was a great[Pg 273] numismatist, and seems to have been a generous, pleasant man. He died in 1784. The sale of his library, prints, and coins lasted fifty-six days. He was, as Leigh Hunt remarks, one of “the earliest persons among the gentry to marry an actress,”[499] setting by that means an excellent example. His wife’s name was Lucretia Bradshaw.

Miss Pope, of Queen Street, had a face grave and unpromising, but her humour was dry and racy as old sherry. Churchill, in the “Rosciad,” mentions her as vivaciously advancing in a jig to perform as Cherry and Polly Honeycomb. Later she grew into an excellent Mrs. Malaprop.[500]

This good woman, well-bred lady, and finished actress, lived for forty years in Queen Street, two doors east of Freemasons’ Tavern; there, the Miss Prue, and Cherry, and Jacinta, and Miss Biddy of years before, the friend of Garrick and the praised of Churchill, sat, surrounded by portraits of Lord Nuneham, General Churchill, Garrick, and Holland, and told the story of her first love to Horace Smith.

An attachment had sprung up between her and Holland, but Garrick had warned her of the man’s waywardness and instability. Miss Pope would not believe the accusations till one day, on her way to see Mrs. Clive at Twickenham, she beheld the unfaithful Holland in a boat with Mrs. Baddeley, near the Eel-pie Island. She accused him at the next rehearsal, he would confess no wrong, and she never spoke to him again but on the stage. “But I have reason to know,” said the old lady, shedding tears as she looked up at her cruel lover’s portrait, “that he never was really happy.”

Miss Pope left Queen Street at last, finding the Freemasons too noisy neighbours, especially after dinner. “Miss Pope,” says Hazlitt, “was the very picture of a duenna or an antiquated dowager in the latter spring of beauty—the second childhood of vanity; more quaint, fantastic, and old-fashioned, more pert, frothy, and light-headed than can be imagined.”[501]

[Pg 274]It was not very easy to please poor soured Hazlitt, whose opinion of women had not been improved by his having been jilted by a servant girl. This good woman, Miss Pope, died at Hadley in 1801, her latter life having been embittered by the loss of her brother and favourite niece.

The Freemasons’ Hall, built by T. Sandby, architect, was opened in 1776, by Lord Petre, a Roman Catholic nobleman, with the usual mysterious ceremonials of the order. The annual assemblies of the lodges had previously been held in the halls of the City’s companies. The tavern was built in 1786, by William Tyler, and has since been enlarged. In the tavern public meetings and dinners take place, chiefly in May and June. Here a farewell banquet was given to John Philip Kemble, and a public dinner on his birthday, to James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd. All the waiters in this tavern are Masons. The house has been lately enlarged. Its new great Hall was inaugurated by the dinner given to Charles Dickens by his friends on his departure for America in November 1857.

Isaac Sparkes, a famous Irish comedian about 1774, was an old, fat, unwieldy man, with a vast double chin, and large, bushy, prominent eyebrows. When in London, he established in Long Acre a Club, which was frequented by Lord Townshend, Lord Effingham, Lord Lindore, Captain Mulcaster, Mr. Crewe of Cheshire, and “other nobles and fashionables.” Sparkes, who dressed well and had a commanding presence, probably presided over it, as he did at Dublin clubs, dressed in robes as Lord Chief Justice Joker.[502]

In one of the grand old houses in Great Queen Street, on the right hand as one goes towards Lincoln’s Inn Fields, occupied before 1830 by Messrs. Allman the booksellers, died Lewis the comedian, famous to the last, as Leigh Hunt tells us, for his invincible airiness and juvenility. “Mr. Lewis,” says the same veteran play-goer, “displayed a combination rarely to be found in acting—that of the fop and the real gentleman. With a voice, a manner, and a person all[Pg 275] equally graceful and light, with features at once whimsical and genteel, he played on the top of his profession like a plume. He was the Mercutio of the age, in every sense of the word mercurial. His airy, breathless voice, thrown to the audience before he appeared, was the signal of his winged animal spirits; and when he gave a glance of his eye or touched with his finger another man’s ribs, it was the very punctum saliens of playfulness and innuendo. We saw him take leave of the public, a man of sixty-five, looking not more than half the age, in the character of the Copper Captain; and heard him say, in a voice broken with emotion, that for the space of thirty years he had not once incurred their displeasure.”[503]

Benjamin Franklin, when first in England, worked at the printing-office of Mr. Watts, in Little Wild Street, after being employed for twelve months at one Palmer’s, in Bartholomew Close. He lodged close by in Duke Street, opposite the Roman Catholic Chapel, with a widow, to whom he paid three-and-sixpence weekly. His landlady was a clergyman’s daughter, who had married a Catholic, and abjured Protestantism. She and Franklin were much together, as he kept good hours and she was lame and almost confined to her room. Their frugal supper often consisted of nothing but half an anchovy, a small slice of bread and butter each, and half a pint of ale between them. On Franklin proposing to leave for cheaper lodgings, she consented to let him retain his room at two shillings a week. In the attic of the house lived a voluntary nun. She was a lady who early in life had been sent to the Continent for her health, but unable to bear the climate, had returned home to live in seclusion on £12 a year, devoting the rest of her income to charity, and subsisting, healthy and cheerful, on nothing but water-gruel. Her presence was thought a blessing to the house, and several tenants in succession had charged her no rent. She permitted the occasional visits of Franklin and his landlady; and the brave American lad, while he pitied her superstition, felt confirmed in his frugality by her example.

[Pg 276]During his first weeks with Mr. Watts, Franklin worked as a pressman, drinking only water while his companions had their five pints of porter daily. The “Water American,” as he was called, was, however, stronger than his colleagues, and tried to persuade some of them that strong beer was not necessary for strong work. His argument was that bread contained more materials of strength than beer, and that it was only corn in the beer that produced the strength in the liquid.

Born to be a reformer, Franklin persuaded the chapel to alter some of their laws; he resisted impositions, and conciliated the respect of his fellows. He worked as a pressman, as he had done in America, for the sake of the exercise. He used, he tells us, to carry up and down stairs with one hand a large form of type, while the other fifty men required both hands to do the same work.

Franklin’s fellow pressman drank every day a pint of beer before breakfast, a pint with bread and cheese for breakfast, a pint between breakfast and dinner, one at dinner, one again at six in the afternoon, and another after his day’s work; and all this he declared to be necessary to give him strength for the press. “This custom,” said the King of Common Sense, “seemed to me abominable.” Franklin, however, failed to make a convert of this man, and he went on paying his four or five shillings a week for the “cursed beverage,” destined probably, poor devil, to remain all his life in a state of voluntary wretchedness, serfdom, and poverty.

A few of the men consented to follow Franklin’s example, and renouncing beer and cheese, to take for breakfast a basin of warm gruel, with butter, toast, and nutmeg. This did not cost more than a pint of beer—“namely, three halfpence”—and at the same time was more nourishing and kept the head clearer. Those who gorged themselves with beer would sometimes run up a score and come to the Water American for credit, “their light being out.” Franklin attended at the great stone table every Saturday evening to take up the little debts, which sometimes amounted to thirty[Pg 277] shillings a week. “This circumstance,” says Franklin in his autobiography, “added to the reputation of my being a tolerable gabber—or, in other words, skilful in the art of burlesque—kept up my importance in the ‘chapel.’ I had, besides, recommended myself to the esteem of my master by my assiduous application to business, never observing ‘Saint’ Monday. My extraordinary quickness in composing always procured me such work as was most urgent, and which is commonly best paid; and thus my time passed away in a very pleasant manner.”[504]

Franklin, like a truly great man, was quietly proud of the humble origin from which he had risen; and when he came to England as the agent and ambassador of Massachusetts, he paid a visit to his work-room in Wild Street, and going to his old friend the press, said to the two workmen busy at it, “Come, my friends, we will drink together; it is now forty years since I worked like you at this very press as a journeyman printer.”

Wild House stood on the site of Little Wild Street. The Duchess of Ormond was living there in 1655.[505]

On the day when King James II. escaped from London the mob grew unruly, and assembled in great force to pull down houses where either mass was said or priests lodged. Don Pietro Ronguillo, the Spanish ambassador, who lived at Wild House, and whom Evelyn mentions as having received him with “extraordinary civility” (March 26, 1681), had not thought it necessary to ask for soldiers, though the rich Roman Catholics had sent him their money and plate as to a sanctuary, and the plate of the Chapel Royal was also in his care. But the house was sacked without mercy; his noble library perished in the flames; the chapel was demolished; the pictures, rich beds, and furniture were destroyed,—the poor Spaniard making his escape by a back door.[506] His only comfort was that the sacred Host in his chapel was rescued.[507]

[Pg 278]In 1780 another savage and thievish Protestant mob, under Lord George Gordon, assembled in St. George’s Fields to petition Parliament against the Test Act, which relieved Roman Catholics from many vexatious penalties and unjust disabilities on condition of their taking their oaths of allegiance and disbelief in the infamous doctrines of the Jesuits. The mob assembled on the 2d of June, and jostled and insulted the Peers going to the House of Lords. The same evening the people demolished the greater part of the Roman Catholic Chapel in Duke Street. On Monday they stripped the house and shop of Mr. Maberly, of Little Queen Street, who had been a witness at the trial of some rioters. On Tuesday they passed through Long Acre and burnt Newgate, releasing three hundred prisoners, and the same day destroyed the house of Justice Cox in Great Queen Street.[508] In these street riots seventy-two private houses and four public gaols were burnt, and more than four hundred rioters perished.

At the above-named chapel Nollekens, the eminent sculptor, was baptized in 1737. The present chapel is much resorted to on Sundays by the Irish poor and foreigners, who live about Drury Lane.

Nicholas Stone, the great monumental sculptor, lived in Long Acre. In 1619 Inigo Jones began the new Banqueting House at Whitehall, and replaced the one destroyed by fire six months before. This master mason was Nicholas Stone,[509] the sculptor of the fine monument to Sir Francis Vere in Westminster Abbey. His pay was 4s. 10d. a day. Stone also designed Dr. Donne’s splendid monument in St. Paul’s. Roubilliac was a great admirer of the kneeling knight at the north-west corner of Vere’s tomb. He used to stand and watch it, and say, “Hush! hush! he vill speak presently.” Mr. J. T. Smith seems to think that the Shakspere monument at Stratford is in this sculptor’s manner.[510] Inigo Jones, who had been fined for having borne arms at[Pg 279] the siege of Basing House, joined with Nicholas Stone in burying their money near Inigo’s house in Scotland Yard; but as the Parliament encouraged servants to betray such hidden treasures, the partners removed their money and hid it again with their own hands in Lambeth Marsh.

Oliver Cromwell, when member for Cambridge, lived from 1637 to 1643, on the south side of Long Acre, two doors from Nicholas Stone the sculptor.

John Taylor, the “Water-Poet” an eccentric poetaster, kept a public-house in Phœnix Alley, now Hanover Court, near Long Acre. He was a Thames waterman, who had fought at the taking of Cadiz, and afterwards travelled to Germany and Scotland as a servant to Sir William Waade. He was then made collector of the wine-dues for the lieutenant of the Tower, and wrote a life of Old Parr, and sixty-three volumes of satire and jingling doggerel, not altogether without vivacity and vigour. He called himself “the King’s Water Poet” and “the Queen’s Waterman;” and in 1623 wrote a tract called “The World runs on Wheels”—a violent attack on the use of coaches. “I dare truly affirm,” says the writer, “that every day in any term (especially if the court be at Whitehall) they do rob us of our livings and carry five hundred and sixty fares daily from us.” In this quaint pamphlet Taylor gives a humorous account of his once riding in his master’s coach from Whitehall to the Tower. “Before I had been drawn twenty yards,” he says, “such a timpany of pride puft me up that I was ready to burst with the wind-cholic of vaine glory.” He complains particularly of the streets and lanes being blocked with carriages, especially Blackfriars and Fleet Street or the Strand after a masque or play at court; the noise deafening every one and souring the beer, to the injury of the public health. It is Taylor who mentions that William Boonen, a Dutchman, first introduced coaches into England in 1564, and became Queen Elizabeth’s coachman. “It is,” he says, “a doubtful question whether the devil brought tobacco into England in a coach, or brought a coach in a fog or mist of tobacco.” Nor did Taylor rest there, for he presented a[Pg 280] petition to James I., which was submitted to Sir Francis Bacon and other commissioners, to compel all play-houses to stand on the Bankside, so as to give more work to watermen. In the Civil War, Taylor went to Oxford and wrote ballads for the king. On his return to London, he settled in Long Acre with a mourning crown for a sign;[511] but the Puritans resenting this emblem, he had his own portrait painted instead with this motto—

“There’s many a head stands for a sign:

Then, gentle reader, why not mine?”

Taylor was born in 1580, and died in 1654; and the following epitaph was written on the vain, honest fellow, who was buried at St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields:—

“Here lies the Water-poet, honest John,

Who rowed on the streams of Helicon;

Where having many rocks and dangers past,

He at the haven of Heaven arrived at last.”[512]

From 1682 to 1686 John Dryden lived in Long Acre, on the north side, in a house facing what formerly was Rose Street. His name appears in the rate-books as “John Dryden, Esq.”—an unusual distinction—and the sum he paid to the poor varied from 18s. to £1.[513] It was here he resided when he was beaten, one December evening in 1679, by three ruffians hired by the Earl of Rochester and the Duchess of Portsmouth. Sir Walter Scott makes the poet live at the time in Gerard Street; but no part of Gerard Street was built in 1679. Rochester had the year before ridiculed Dryden as “Poet Squab,” and believed that Dryden had helped Mulgrave in ridiculing him in his clumsy “Essay on Satire.” The best lines of this dull poem are these:—

“Of fighting sparks Fame may her pleasure say,

But ’tis a bolder thing to run away.

The world may well forgive him all his ill,

For every fault does prove his penance still;

Falsely he falls into some dangerous noose,

And then as meanly labours to get loose.”

[Pg 281]A letter from Rochester to a friend, dated November 21, in the above year, is still extant, in which he names Dryden as the author of the satire, and concludes with the following threat:—“If he (Dryden) falls on me at the blunt, which is his very good weapon in wit, I will forgive him, if you please, and leave the repartee to Black Will with a cudgel.”[514]

Dryden offered a reward of fifty pounds for the discovery of the men who cudgelled him, depositing the money in the hands of “Mr. Blanchard, goldsmith, next door to Temple Bar,” but all in vain. The Rose Alley satire, the Rose Alley ambuscade, and the Dryden salutation, became established jokes with Dryden’s countless enemies. Even Mulgrave himself, in his Art of Poetry said of Dryden coldly—

“Though praised and punished for another’s rhymes,

His own deserve as great applause sometimes.”

And, in a conceited note, the amateur poet described the libel as one for which Dryden had been unjustly “applauded and wounded.” But these lines and this note Mulgrave afterwards suppressed.

Poor Otway, whom Rochester had satirised, and who had accused Dryden of saying of his Don Carlos that, “Egad, there was not a line in it he would be author of,” stood up bravely for Dryden as an honest satirist in these vigorous verses:—

“Poets in honour of the truth should write,

With the same spirit brave men for it fight.

*****

From any private cause where malice reigns,

Or general pique all blockheads have to brains.”

Dryden never took any poetical revenge on Rochester, and in the prefatory essay to his Juvenal he takes credit for that forbearance.[515]

Edward (more generally known as Ned) Ward was the landlord of public-houses alternately in Moorfields, Clerkenwell, Fulwood’s Rents, and Long Acre. He was born in 1667, and died 1731. He was a High Tory, and fond[Pg 282] of the society of poets and authors.[516] Attacked in the Dunciad, he turned Don Quixote into Hudibrastic verse, and wrote endless songs, lampoons, coarse clever satires, and Dialogues on Matrimony (1710).

The father of Pepys’s long-suffering wife lived in Long Acre; and the bustling official describes, with a stultifying exactitude, his horror at a visit which he found himself forced to pay to a house surrounded by taverns.

Dr. Arbuthnot, in a letter to Mr. Watkins, gives Bessy Cox—a woman in Long Acre whom Prior would have married when her husband died—a detestable character. The infatuated poet left his estate between his old servant Jonathan Drift, and this woman, who boasted that she was the poet’s Emma,—another virago, Flanders Jane, being his Chloe.[517]

It is said of this careless, pleasant poet, that after spending an intellectual evening with Oxford, Bolingbroke, Pope, and Swift, in order to unbend, he would smoke a pipe and drink a bottle of ale with a common soldier and his wife in Long Acre. Cibber calls the man a butcher;[518] other writers make him a cobbler or a tavern-keeper, which is more likely. The shameless husband is said to have been proud of the poet’s preference for his wife. Pope, who was remorseless at the failings of friends, calls the woman a wretch, and said to Spence, “Prior was not a right good man; he used to bury himself for whole days and nights together with this poor mean creature, and often drank hard.” This person, who perhaps is misrepresented—and where there is a doubt the prisoner at the bar should always have the benefit of it—was the Venus of the poet’s verse. To her Prior wrote, after Walpole tried to impeach him:—

“From public noise and faction’s strife,

From all the busy ills of life,

Take me, my Chloe, to thy breast,

And lull my wearied soul to rest.

[Pg 283]

“For ever in this humble cell [ale-house]

Let thee and I [me], my fair one, dwell;

None enter else but Love, and he

Shall bar the door and keep the key.”

Prior was the son of a joiner,[519] and was brought up, as before mentioned, by his uncle, a tavern-keeper at Charing Cross, where the clever waiter’s knowledge of Horace led to his being sent to college by the Earl of Dorset. Abandoning literature, he finally became our ambassador to France. He died in retirement in 1721.

It was in a poor shoemaker’s small window in Long Acre,—half of it devoted to boots, half to pictures—that poor starving Wilson’s fine classical landscapes were exposed, often vainly, for sale. Here, from his miserable garret in Tottenham Court Road, the great painter, peevish and soured by neglect, would come swearing at his rivals Barret and Smith of Chichester. I can imagine him, with his tall, burly figure, his red face, and his enormous nose, striding out of the shop, thirsting for porter, and muttering that, if the pictures of Wright of Derby had fire, his had air. Yet this great painter, whose works are so majestic and glowing, so fresh, airy, broad, and harmonious, was all but starved. The king refused to purchase his “Kew Gardens,” and the very pawnbrokers grew weary of taking his Tivolis and Niobes as pledges, far preferring violins, flat-irons, or telescopes.

It was in Long Acre that that delightful idyllic painter, Stothard, was born in 1755. His father, a Yorkshireman, kept an inn in the street.[520] Sent for his health into Yorkshire, and placed with an old lady who had some choice engravings, he began to draw. The first subject that he ever painted was executed with an oyster-shell full of black paint, borrowed from the village plumber and glazier. This little man was the father of many a Watteau lover and tripping Boccaccio nymph. That genial and graceful artist, who illustrated Chaucer, Robinson Crusoe, and The Pilgrim’s [Pg 284]Progress, had the road to fame pointed out to him first by that little black man.

On the accession of King George I. the Tories had such sway over the London mobs, that the friends of the Protestant succession resolved to found cheap tavern clubs in various parts of the City in order that well-affected tradesmen might meet to keep up their spirit of loyalty, and serve as focus-points of resistance in case of Tory tumults.

Defoe, a staunch Whig, describes one of these assemblies in Long Acre, which probably suggested the rest. At the Mughouse Club in Long Acre, about a hundred gentlemen, lawyers, and tradesmen met in a large room, at seven o’clock on Wednesday and Saturday evenings in the winter, and broke up soon after ten. A grave old gentleman, “in his own grey hairs,”[521] and within a few months of ninety, was the president, and sat in an “armed” chair, raised some steps above the rest of the company, to keep the room in order. A harp was played all the time at the lower end of the room, and every now and then one of the company rose and entertained the rest with a song. Nothing was drunk but ale, and every one chalked his score on the table beside him. What with the songs and drinking healths from one table to another, there was no room for politics or anything that could sour conversation. The members of these clubs retired when they pleased, as from a coffee-house.

Old Sir Hans Sloane’s coach, made by John Aubrey, Queen Anne’s coachmaker, in Long Acre, and given to him by her for curing her of a fit of the gout, was given by Sir Hans to his old butler, who set up the White Horse Inn behind Chelsea Church, where it remained for half a century.[522]

Charles Catton, one of the early Academicians, was originally a coach and sign painter. He painted a lion as a sign for his friend, a celebrated coachmaker, at that time living in Long Acre.[523] A sign painted by Clarkson, that hung at the north-east corner of Little Russell Street about 1780, was[Pg 285] said to have cost £500, and crowds used to collect to look at it.

Lord William Russell was led from Holborn into Little Queen Street on his way to the scaffold in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. As the coach turned into this street, Lord Russell said to Tillotson, “I have often turned to the other hand with great comfort, but I now turn to this with greater.” He referred to Southampton House, on the opposite side of Holborn, which he inherited through his brave and good wife, the grand-daughter of Shakspere’s early patron.

In the year 1796 Charles Lamb resided with his father, mother, aunt, and sister in lodgings at No. 7 Little Queen Street, a house, I believe, removed to make way for the church. Southey describes a call which he made on them there in 1794-5. The father had once published a small quarto volume of poetry, of which “The Sparrow’s Wedding” was his favourite, and Charles used to delight him by reading this to him when he was in his dotage. In 1797 Lamb published his first verses. His father, the ex-servant and companion of an old Bencher in the Temple, was sinking into the grave; his mother had lost the use of her limbs, and his sister was employed by day in needlework, and by night in watching her mother. Lamb, just twenty-one years old, was a clerk in the India House. On the 22d of September[524] Miss Lamb, who had been deranged some years before by nervous fatigue, seized a case-knife while dinner was preparing, chased a little girl, her apprentice, round the room, and on her mother calling to her to forbear, stabbed her to the heart. Lamb arrived only in time to snatch the knife from his sister’s hand. He had that morning been to consult a doctor, but had not found him at home. The verdict at the inquest was “Insanity,” and Mary Lamb was sent to a mad-house, where she soon recovered her reason. Poor Lamb’s father and aunt did not long survive. Not long after, Lamb himself was for six weeks confined in an asylum. There is extant a terrible letter in which he describes rushing from a party of friends who were supping[Pg 286] with him soon after the horrible catastrophe, and in an agony of regret falling on his knees by his mother’s coffin, asking forgiveness of Heaven for forgetting her so soon.[525]

There is no doubt that poor Lamb played the sot over his nightly grog; but he had a noble soul, and let us be lenient with such a man—

“Be to his faults a little blind,

And to his virtues very kind.”

He abandoned her whom he loved, together with all meaner ambitions, and drudged his years away as a poor, ignoble clerk, in order to maintain his half-crazed sister; for this purpose—true knight that he was, though he never drew sword—he gave all that he had—HIS LIFE! Peace, then! peace be to his ashes!

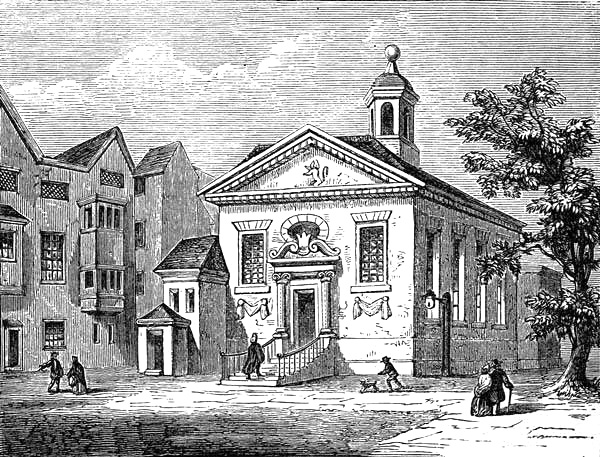

LYON’S INN, 1804.

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:12:52 GMT