Haunted London, Index

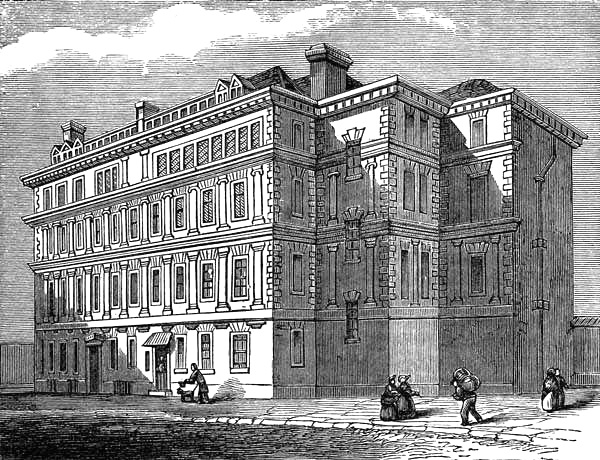

CRAVEN HOUSE, 1790.

CHAPTER XII.

DRURY LANE.

The Roll of Battle Abbey tells us that the founder of the Drury family came into England with that brave Norman robber, the Conqueror, and settled in Suffolk.[526]

From this house branched off the Druries of Hawstead, in the same county, who built Drury House in the time of Elizabeth. It stood a little behind the site of the present Olympic Theatre. Of another branch of the same family was that Sir Drue Drury, who, together with Sir Amias[Pg 288] Powlett, had at one time the custody of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Drury Lane takes its name from a house probably built by Sir William Drury, a Knight of the Garter, and a most able commander in the desultory Irish wars during the reign of Elizabeth, who fell in a duel with John Burroughs, fought to settle a foolish quarrel about some punctilio of precedency.[527] In this house, in 1600, the imprudent friends of rash Essex resolved on the fatal outbreak that ended so lamentably at Ludgate. The Earl of Southampton then resided there.[528] The plots of Blount, Davis, Davers, etc., were communicated to Essex by letter. It was noticed that at his trial the earl betrayed agitation at the mention of Drury House, though he had carefully destroyed all suspicious papers.

Sir William’s son Robert was a patron of Dr. Donne, the religious poet and satirist, who in 1611 had apartments assigned to him and his wife in Drury House. Donne, though the son of a man of some fortune, was foolish enough to squander his money when young, and in advanced life was so wanting in self-respect as to live about in other men’s houses, paying for his food and lodging by his wit and conversation. He lived first with Lord Chancellor Egerton, Bacon’s predecessor, afterwards at Drury House and with Sir Francis Wooley at Pitford, in Surrey. After his clandestine marriage with Lady Ellesmere’s niece, Donne’s life was for some time a hard and troublesome one.

“Sir Robert Drury,” says Isaac Walton, “a gentleman of a very noble estate and a more liberal mind, assigned Donne and his wife a useful apartment in his own large house in Drury Lane, and rent free; he was also a cherisher of his studies, and such a friend as sympathised with him and his in all their joys and sorrows.”[529]

Sir Robert, wishing to attend Lord Hay as King James’s ambassador at his audiences in Paris with Henry IV., begged Donne to accompany him. But the poet refused, his wife[Pg 289] being at the time near her confinement and in poor health, and saying that “her divining soul boded some ill in his absence.” But Sir Robert growing more urgent, and Donne unwilling to refuse his generous friend a request, at last obtained from his wife a faint consent for a two months’ absence. On the twelfth day the party reached Paris. Two days afterwards Donne was left alone in the room where Sir Robert and other friends had dined. Half an hour afterwards Sir Robert returned, and found Mr. Donne still alone, “but in such an ecstasy, and so altered in his looks,” as amazed him. After a long and perplexed pause, Donne said, “I have had a dreadful vision since I saw you; I have seen my dear wife pass by me twice in this room with her hair hanging about her shoulders and a dead child in her arms;” to which Sir Robert replied, “Sure, sir, you have slept since I saw you, and this is the result of some melancholy dream, which I desire you to forget, for you are now awake.” Donne assured his friend that he had not been asleep, and that on the second appearance his wife stopped, looked him in the face, and then vanished.

The next day, however, neither rest nor sleep had altered Mr. Donne’s opinion, and he repeated the story with only a more deliberate and confirmed confidence. All this inclining Sir Robert to some faint belief, he instantly sent off a servant to Drury House to bring him word in what condition Mrs. Donne was. The messenger returned in due time, saying that he had found Mrs. Donne very sad and sick in bed, and that after a long and dangerous labour she had been delivered of a dead child; and upon examination, the delivery proved to have been at the very day and hour in which Donne had seen the vision. Walton is proud of this late miracle, so easily explainable by natural causes; and illustrates the sympathy of souls by the story of two lutes, one of which, if both are tuned to the same pitch, will, though untouched, echo the other when it is played.

Far be it from me to wish to ridicule any man’s belief in the supernatural; but still, as a lover of truth, wishing to believe what is, whether natural or supernatural, without[Pg 290] confusing the former with the latter, let me analyse this pictured presentiment. An imaginative man, against his sick wife’s wish, undertakes a perilous journey. Absent from her—alone—after wine and friendly revel feeling still more lonely—in the twilight he thinks of home and the wife he loves so much. Dreaming, though awake, his fears resolve themselves into a vision, seen by the mind, and to the eye apparently vivid as reality. The day and hour happen to correspond, or he persuades himself afterwards that they do correspond with the result, and the day-dream is henceforward ranked among supernatural visions. Who is there candid enough to write down the presentiments that do not come true? And after all, the vision, to be consistent, should have been followed by the death of Mrs. Donne as well as the child.

Some verses are pointed out by Isaac Walton as those written by Donne on parting from her for this journey. But there is internal evidence in them to the contrary; for they refer to Italy, not to Paris, and to a lady who would accompany him as a page, which a lady in Mrs. Donne’s condition could scarcely have done. I have myself no doubt that the verses cited were written to his wife long before, when their marriage was as yet concealed. With what a fine vigour the poem commences!—

“By our first strange and fatal interview,

By all desires which thereof did ensue,

By our long-striving hopes, by that remorse

Which my words’ masculine persuasive force

Begot in thee, and by the memory

Of hurts which spies and rivals threaten me!”

*****

And how full of true feeling and passionate tenderness is the dramatic close!—

“When I am gone dream me some happiness,

Nor let thy looks our long-hid love confess;

Nor praise nor dispraise me; nor bless nor curse

Openly love’s force; nor in bed fright thy nurse

With midnight startings, crying out, ‘Oh! oh!

[Pg 291]Nurse! oh, my love is slain! I saw him go

O’er the white Alps alone; I saw him, I,

Assailed, taken, fight, stabbed, bleed, and die.’”

The verses really written on Donne’s leaving for Paris begin with four exquisite lines—

“As virtuous men pass mild away,

And whisper to their souls to go,

Whilst some of their sad friends do say,

‘The breath goes now,’ and some say ‘No!’”

A later verse contains a strange conceit, beaten out into pin-wire a page long by a modern poet—[530]

“If we be two, we are two so

As stiff twin compasses are two;

Thy soul, the fix’d foot, makes no show

To move, but does if t’other do.”

Donne was the chief of what Dr. Johnson unwisely called “the metaphysical school of poetry.” Dryden accuses Donne of perplexing the fair sex with nice speculations.[531] His poems, often pious and beautiful, are sometimes distorted with strange conceits. He has a poem on a flea; and in his lines on Good Friday he thus whimsically expresses himself:—

“Who sees God’s face—that is, self-life—must die:

What a death were it then to see God die!

It made his own lieutenant, Nature, shrink;

It made his footstool crack and the sun wink.

Could I behold those hands, which span the Poles,

And tune all sphears at once, pierced with those holes!”[532]

This imitator of the worst faults of Marini was made Dean of St. Paul’s by King James I., who delighted to converse with him. The king used to say, “I always rejoice when I think that by my means Donne became a divine.” He gave the poet the deanery one day as he sat at dinner, saying “that he would carve to him of a dish he loved well, and that he might take the dish (the deanery) home to his study and say grace there to himself, and much good might it do him.”

[Pg 292]Shortly before his death Donne dressed himself in his shroud, and standing there, with his eyes shut and the sheet opened, “To discover his thin, pale, and death-like face,” he caused a curious painter to take his picture. This picture he kept near his bed as a ghostly remembrance, and from this Nicholas Stone, the sculptor, carved his effigy, which still exists in St. Paul’s, having survived the Great Fire, though the rest of his tomb and monument has perished.

Drury House took the name of Craven House when rebuilt by Lord Craven. There is a tradition in Yorkshire, where the deanery of Craven is situated, that this chivalrous nobleman’s father was sent up to London by the carrier, and there became a mercer or draper. His son was not unworthy of the staunch old Yorkshire stock. He fought under Gustavus Adolphus against Wallenstein and Tilly, and afterwards attached himself to the service of the unfortunate King and Queen of Bohemia, and won wealth and a title for his family, which the Wars of the Roses had first reduced to indigence.

The Queen of Bohemia had been married in 1613 to Frederic, Count Palatine of the Rhine, only a few months after the death of Prince Henry her brother. The young King of Spain had been her suitor, and the Pope had opposed her match with a Protestant. She was married on St. Valentine’s Day; and Donne, from his study in Drury Lane, celebrated the occasion by a most extravagant epithalamion in which is to be found this outrageous line—

“Here lies a She sun, and a He moon there.”

The poem opens prettily enough with these lines—

“Hail, Bishop Valentine, whose day this is!

All the air is thy diocese;

And all the chirping choristers

And other birds are thy parishioners.

Thou marry’st every year

The lyrique lark and the grave whispering dove.”

At seventeen Sir William Craven had entered the service[Pg 293] of the Prince of Orange. On the accession of Charles I. he was ennobled. At the storming of Creuzenach he was the first of the English Cavaliers to mount the breach and plant the flag. It was then that Gustavus said smilingly to him, “I perceive, sir, you are willing to give a younger brother a chance of coming to your title and estate.” At Donauwert the young Englishman again distinguished himself. In the same month that Gustavus fell at Lutzen, the Elector Palatine died at Mentz. While Grotius interceded for the Queen of Bohemia, Lord Craven fought for her in the vineyards of the Palatinate.[533] In consequence, perhaps, of Richelieu’s intrigues, four years elapsed before Charles I. took compassion on the children of his widowed sister, whose cause the Puritans had loudly advocated. When Charles and Rupert did go to England, they went under the care of the trusty Lord Craven, who was to try to recover the arrears of the widow’s pension. On their return to Germany, to campaign in Westphalia, Rupert and Lord Craven were taken prisoners and thrown into the castle at Vienna—a confinement that lasted three years, a long time for brave young soldiers who, like the Douglas, “preferred the lark’s song to the mouse’s squeak.”

Later in the Civil War we find this same generous nobleman giving £50,000 to King Charles, at a time when he was a beggar and a fugitive. Cromwell, enraged at the aid thus ministered to an enemy, accused the Cavalier of enlisting volunteers for the Stuart, and instantly, with stern promptitude, sequestered all his English estates except Combe Abbey. In the meantime Lord Craven served the State and his queen bravely, and waited for better times. It was this faithful servant who consoled the royal widow for her son’s ill-treatment, the slander heaped upon her daughter, and the incessant vexations of importunate creditors.

The Restoration brought no good news for the unfortunate queen. Charles, afraid of her claims for a pension, delayed her return to England, till the Earl of Craven[Pg 294] generously offered her a house next his own in Drury Lane. She found there a pleasant and commodious mansion, surrounded by a delightful garden.[534] It does not appear that she went publicly to court, or joined in the royal revelries; but she visited the theatres with her nephew Charles and her good old friend and host, and she was reunited to her son Rupert.

In the autumn of 1661, the year after the Restoration, she removed to Leicester House, then the property of Sir Robert Sydney, Earl of Leicester, and in the next February she died.[535] Evelyn mentions a violent tempestuous wind that followed her death, as a sign from Heaven to show that the troubles and calamities of this princess and of the royal family in general had now all blown over, and were, like the ex-queen, to rest in repose.

She left all her books, pictures, and papers to her incomparable old friend and benefactor. The Earl of Leicester wrote to the Earl of Northumberland a cold and flippant letter to announce the departure of “his royal tenant;” and adds, “It seems the Fates did not think it fit I should have the honour, which indeed I never much desired, to be the landlord of a queen.” Charles, who had grudged the dethroned queen even her subsistence, gave her a royal funeral in Westminster Abbey.

At the very time when she died Lord Craven was building a miniature Heidelberg for her at Hampstead Marshall, in Berkshire, under the advice of that eminent architect and charlatan, Sir Balthasar Gerbier. But the palace was ill-fated, like the poor queen, for it was consumed by an accidental fire before it could be tenanted. The arrival of the Portuguese Infanta, a princess scarcely less unfortunate than the queen just dead, soon erased all recollections of King James’s ill-starred daughter.

The biographers of the Queen of Bohemia do not claim for her beauty, wit, learning, or accomplishments; but she seems to have been an affectionate, romantic girl, full of[Pg 295] vivacity and ambition, who was ripened by sorrow and disappointment into an amiable and high-souled woman.

It was always supposed that the Queen of Bohemia was secretly married to Lord Craven, as Bassompierre was to a princess of Lorraine. A base and abandoned court could not otherwise account for a friendship so unchangeable and so unselfish. There is also a story that when Craven House was pulled down, a subterranean passage was discovered joining the eastern and western sides. Similar passages have been found joining convents to monasteries; but, unfortunately for the scandalmongers, they are generally proved to have been either sewers or conduits. The “Queen of Hearts,” as she was called—the princess to whose cause the chivalrous Christian of Brunswick, the knight with the silver arm, had solemnly devoted his life and fortunes—the “royal mistress” to whom shifty Sir Henry Wotton had written those beautiful lines—

“You meaner beauties of the night,

That poorly entertain our eyes

More by your number than your light,

What are ye when the moon doth rise?”

was at “last gone to dust.” Her faithful servant, the old soldier of Gustavus, survived her thirty-five years, and lived to follow to the grave his foster-child in arms, Prince Rupert, whose daughter Ruperta was left to his trusty guardianship.

In 1670, on the death of the stolid and drunken Duke of Albemarle, Charles II. constituted Lord Craven colonel of the Coldstreams. Energetic, simple-hearted, benevolent, this good servant of a bad race became a member of the Royal Society, lived in familiar intimacy with Evelyn and Ray, improved his property, and employed himself in gardening.

Although he had many estates, Lord Craven always showed the most predilection for Combe Abbey, the residence of the Queen of Bohemia in her youth. To judge by the numerous dedications to which his name is prefixed, he would appear to have been a munificent patron of letters,[Pg 296] especially of those authors who had been favourites of Elizabeth of Bohemia.[536]

On the accession of James, Lord Craven, true as ever, was sworn of the Privy Council; but soon after, on some mean suspicion of the king, was threatened with the loss of his regiment. “If they take away my regiment,” said the staunch old soldier, “they had as good take away my life, since I have nothing else to divert myself with.” In the hurry of the Popish catastrophe it was not taken away. But King William proved Craven’s loyalty to the Stuarts by giving his regiment to General Talmash.

The unemployed officer now expended his activity in attending riots and fires. Long before, when the Puritan prentices had pulled down the houses of ill-fame in Whettone Park and in Moorfields, Pepys had described the colonel as riding up and down like a madman, giving orders to his men. Later Lord Dorset had spoken of the old soldier’s energy in a gay ballad on his mistress—

“The people’s hearts leap wherever she comes,

And beat day and night like my Lord Craven’s drums.”

In King William’s reign the veteran was so prompt in attending fires that it used to be said his horse smelt a fire as soon as it broke out.

Lord Craven died unmarried in 1697, aged 88, and was buried at Binley, near Coventry. The grandson of a Wharfdale peasant had ended a well-spent life. His biographer, Miss Benger, well remarks:—“If his claims to disinterestedness be contemned of men, let his cause be (left) to female judges,—to whose honour be it averred, examples of nobleness, generosity and magnanimity are ever delightful, because to their purer and more susceptible souls they are (never) incredible.”[537]

Drury House was rebuilt by Lord Craven after the Queen’s death. It occupied the site of Craven Buildings and the Olympic Theatre. Pennant, ever curious and energetic, went to find it, and describes it in his pleasant[Pg 297] way as a “large brick pile,” then turned into a public-house bearing the sign of the Queen of Bohemia, faithful still to the worship of its old master.

The house was taken down in 1809, when the Olympic Pavilion was built on part of its gardens. The cellars, once stored with good Rhenish from the Palatinate, and sack from Cadiz, still exist, but have been blocked up. Palsgrave Place, near Temple Bar, perpetuates the memory of the unlucky husband of the brave princess.

It was Lord Craven who generously founded pest-houses in Carnaby Street, soon after the Great Plague. There were thirty-six small houses and a cemetery. They were sold in 1772 to William, third Earl of Craven, for £1200. It may be remembered that in the Memoirs of Scriblerus a room is hired for the dissection of the purchased body of a malefactor, near the St. Giles’s pest-fields, and not far from Tyburn Road, Oxford Street. The Earl was their founder.

On the end wall at the bottom of Craven Buildings there was formerly a large fresco-painting of the Earl of Craven, who was represented in armour, mounted on a charger, and with a truncheon in his hand. This portrait had been twice or thrice repainted in oil, but in Brayley’s time was entirely obliterated.[538] This fresco is said to have been the work of Paul Vansomer, a painter who came to England from Antwerp about 1606, and died in 1621. He painted the Earl and Countess of Arundel, and there are pictures by him at Hampton Court. He also executed the pleasant and quaint hunting scene, with portraits of Prince Henry and the young Earl of Essex, now at St. James’s Palace.[539]

Mr. Moser, keeper of the Royal Academy, a chaser of plate, cane-heads, and watch-cases, afterwards an enameller of watch-trinkets, necklaces, and bracelets, lived in Craven Buildings, which were built in 1723 on part of the site of Craven House. He died in his apartments in Somerset House in 1783.

It was in Short’s Gardens, Drury Lane, “in a hole,” that[Pg 298] Charles Mathews the elder made one of his first attempts as an actor.

Clare House Court, on the left hand going up Drury Lane, derived its name from John Holles, second Earl of Clare, whose town house stood at the end of this court. His son Gilbert, the third Earl, died in 1689, and was succeeded by his son, John Holles, created Marquis of Clare and Duke of Newcastle in 1694. He died in 1711, when all his honours became extinct. The corner house has upon it the date 1693.[540]

In the reign of James I., when Gondomar, the Spanish ambassador, lived at Ely House, in Holborn, he used to pass through Drury Lane in his litter on his way to Whitehall, Covent Garden being then an enclosed field, and this district and the Strand the chief resorts of the gentry. The ladies, knowing his hours, would appear in their balconies or windows to present their civilities to the old man, who would bend himself as well as he could to the humblest posture of respect. One day, as he passed by the house of Lady Jacob in Drury Lane, she presented herself: he bowed to her, but she only gaped at him. Curious to see if this yawning was intentional or accidental, he passed the next day at the same hour, and with the same result. Upon which he sent a gentleman to her to let her know that the ladies of England were usually more gracious to him than to encounter his respects with such affronts. She answered that she had a mouth to be stopped as well as others. Gondomar, finding the cause of her distemper, sent her a present, an antidote which soon cured her of her strange complaint.[541] This Lady Jacob became the wife of the poet Brooke.

That credulous gossip, the Wiltshire gentleman, Aubrey, tells a quaint story of a duel in Drury Lane, in probably Charles II.’s time, which is a good picture of such rencontres amongst the hot-blooded bravos of that wild period.

“Captain Carlo Fantom, a Croatian,” he says, “who spoke thirteen languages, was a captain under the Earl of[Pg 299] Essex. He had a world of cuts about his body with swords, and was very quarrelsome. He met, coming late at night out of the Horseshoe Tavern in Drury Lane, with a lieutenant of Colonel Rossiter, who had great jingling spurs on. Said he, ‘The noise of your spurs doe offend me; you must come over the kennel and give me satisfaction.’ They drew and passed at each other, and the lieutenant was runne through, and died in an hour or two, and ’twas not known who killed him.”[542]

About this time John Lacy, Charles II.’s favourite comedian, the Falstaff of Dryden’s time, lived in Drury Lane from 1665 till his death in 1681. The ex-dancing-master and lieutenant dwelt near Cradle Alley and only two doors from Lord Anglesey.

Drury Lane, though it soon began to deteriorate, had fashionable inhabitants in Charles II.’s time. Evelyn, that delightful type of the English gentleman, mentions in his Diary the marriage of his niece to the eldest son of Mr. Attorney Montague at Southampton Chapel, and talks of a magnificent entertainment at his sister’s “lodgings” in Drury Lane. Steele, however, branded its disreputable districts; Gay[543] warned us against “Drury’s mazy courts and dark abodes;” and Pope laughed at building a church for “the saints of Drury Lane,” and derided its proud and paltry “drabs.” The little sour poet, snugly off and well housed, delighted to sneer, with a cruel and ungenerous contempt, at the poverty of the poor Drury Lane poet who wrote for instant bread:—

“‘Nine years!’ cries he, who, high in Drury Lane,

Lull’d by soft zephyrs through the broken pane,

Rhymes ere he wakes, and prints before Term ends,

Obliged by hunger and request of friends.”

To ridicule poverty, and to treat misfortune as a punishable crime, is the special opprobrium of too many of the heroes of English literature.

Hogarth has shown us the poor poet of Drury Lane; Goldsmith has painted for us the poor author, but in a[Pg 300] kindlier way, for he must have remembered how poor he himself and Dr. Johnson, Savage, Otway, and Lee had been. Pope, in his notes to the Dunciad, expressly says that the poverty of his enemies is the cause of all their slander. Poverty with him is another name for vice and all uncleanness. Goldsmith only laughs as he describes the poor poet in Drury Lane in a garret, snug from the Bailiff, and opposite a public-house famous for Calvert’s beer and Parsons’s “black champagne.” The windows are dim and patched; the floor is sanded. The damp walls are hung with the royal game of goose, the twelve rules of King Charles, and a black profile of the Duke of Cumberland. The rusty grate has no fire. The mantelpiece is chalked with long unpaid scores of beer and milk. There are five cracked teacups on the chimney-board; and the poet meditates over his epics and his finances with a stocking round his brows “instead of bay.”

Early in the reign of William III. Drury Lane finally lost all traces of its aristocratic character.

Vinegar Yard, in Drury Lane, was originally called Vine Garden Yard. Vine Street, Piccadilly, Vine Street, Westminster, and Vine Street, Saffron Hill, all derived their names from the vineyards they displaced; but there is great reason to suppose that in the Middle Ages orchards and herb-gardens were often classified carelessly as “vineyards.” English grapes might produce a sour, thin wine, but there was never a time when home-made wine superseded the produce of Montvoisin, Bordeaux, or Gascony. Vinegar Yard was built about 1621.[544] In St Martin’s Burial Register there is an entry, “1624, Feb. 4: Buried Blind John out of Vinagre Yard.” Clayrender’s letter in Smollett’s Roderick Random is written to her “dear kreetur” from “Winegar Yard, Droory Lane.” This fair charmer must surely have lived not far from Mr. Dickens’s inimitable Mrs. Megby. The nearness of Vinegar Yard to the theatre is alluded to by James Smith in his parody on Sir Walter Scott in the Rejected Addresses.

[Pg 301]General Monk’s gross and violent wife was the daughter of his servant, John Clarges, a farrier in the Savoy. Her mother, says Aubrey, was one of the five women-barbers[545] that lived in Drury Lane. She kept a glove-shop in the New Exchange before her marriage, and as a seamstress used to carry the general’s linen to him when he was in the Tower.

Pepys hated her, because she was jealous of his patron, Lord Sandwich, and called him a coward. He calls her “ill-looking” and “a plain, homely dowdy,” and says that one day, when Monk was drunk, and sitting with Troutbeck, a disreputable fellow, the duke was wondering that Nan Hyde, a brewer’s daughter, should ever have come to be Duchess of York. “Nay,” said Troutbeck, “ne’er wonder at that, for if you will give me another bottle of wine I will tell you as great if not a greater miracle, and that was that our Dirty Bess should come to be Duchess of Albemarle.”[546]

Nell Gwynn was born in Coal Yard, on the east side of Drury Lane,[547] the next turning to the infamous Lewknor Lane, which used to be inhabited by the orange-girls who attended the theatres in Charles II.’s reign. It was in this same lane that Jonathan Wild, the thief-taker, whom Fielding immortalises, afterwards lived. In a coarse and ruthless satire written by Sir George Etherege after Nell’s death, the poet calls her a “scoundrel lass,” raised from a dunghill, born in a cellar, and brought up as a cinder-wench in a coalyard.[548]

Nelly was the vagabond daughter of a poor Cavalier captain and fruiterer, who is said to have died in prison at Oxford. She began life by selling fish in the street, then turned orange-girl at the theatres, was promoted to be an actress, and finally became a mistress of Charles II. Though not as savage-tempered as the infamous Lady Castlemaine, Nelly was almost as mischievous, and quite as shameless.[Pg 302] She obtained from the king £60,000 in four years.[549] She bought a pearl necklace at Prince Rupert’s sale for £4000. She drank, swore, gambled, and squandered money as wildly as her rivals. Nelly was small, with a good-humoured face, and “eyes that winked when she laughed.”[550] She was witty, reckless, and good-natured. The portrait of her by Lely, with the lamb under her arm, shows us a very arch, pretty, dimply little actress. The present Duke of St. Alban’s is descended from her.[551]

In 1667 Nell Gwynn was living in Drury Lane, for on May day of that year Pepys says—“To Westminster, in the way meeting many milkmaids with garlands upon their pails, dancing with a fiddler between them; and saw pretty Nelly standing at her lodging’s door in Drury Lane, in her smock-sleeves and boddice, looking upon one. She seemed a mighty pretty creature.” Nelly had not then been long on the stage, and Pepys had hissed her a few months before being introduced to her by dangerous Mrs. Knipp. In 1671 Evelyn saw Nelly, then living in Pall Mall, “looking out of her garden on a terrace at the top of the wall,” and talking too familiarly to the king, who stood on the green walk in the park below.[552]

Poor Nell was not “allowed to starve,” but ended an ill life by dying of apoplexy. There is no authority for the name of “Nell Gwynn’s Dairy” given to a house near the Adelphi.

That infamous and perjured scoundrel, and the murderer of so many innocent men, Titus Oates, was the son of a popular Baptist preacher in Ratcliffe Highway, and was educated at Merchant Taylor’s. Dismissed from the Fleet, of which he was chaplain, for infamous practices, he became a Jesuit at St. Omer’s, and came back to disclose the sham Popish plot, for which atrocious lie he received of the Roman Catholic king, Charles II., £1200 a year, an[Pg 303] escort of guards, and a lodging in Whitehall. Oates died in 1705. He lodged for some time in Cockpit Alley, now called Pitt Place.

It was in the Crown Tavern, next the Whistling Oyster, and close to the south side of Drury Lane Theatre, that Punch was first projected by Mr. Mark Lemon and Mr. Henry Mayhew in 1841; and its first number was “prepared for press” in a back room in Newcastle Street, Strand. Great rivers often have their sources in swampy and obscure places, and our good-natured satirist has not much to boast of in its birthplace. To Punch Tom Hood contributed his immortal “Song of the Shirt,” and Tennyson his scorching satire against Bulwer and his “New Timon;” almost from the first, Leech devoted to it his humorous pencil, and Albert Smith his perennial store of good humour and drollery. Amongst its other early contributors should be mentioned Mr. Gilbert A. à Beckett, Mr. W. H. Wills, and Douglas Jerrold.

Zoffany, the artist, lived for some time in poverty in Drury Lane. Mr. Audinet, father of Philip Audinet the engraver, served his time with the celebrated clockmaker, Rimbault, who lived in Great St. Andrew’s Street, Seven Dials. This worthy excelled in the construction of the clocks called at that time “Twelve-tuned Dutchmen,” which were contrived with moving figures, engaged in a variety of employments. The pricking of the barrels of those clocks was performed by Bellodi, an Italian, who lived hard by, in Short’s Gardens, Drury Lane. This person solicited Rimbault in favour of a starving artist who dwelt in a garret in his house. “Let him come to me,” said Rimbault. Accordingly Zoffany waited upon the clockmaker, and produced some specimens of his art, which were so satisfactory that he was immediately set to work to embellish clock-faces, and paint appropriate backgrounds to the puppets upon them. From clock-faces the young painter proceeded to the human face divine, and at last resolved to try his hand upon the visage of the worthy clockmaker himself. He hit off the likeness of the patron so successfully,[Pg 304] that Rimbault exerted himself to serve and promote him. Benjamin Wilson, the portrait-painter, who at that time lived at 56 Great Russell Street, a house afterwards inhabited by Philip Audinet, being desirous of procuring an assistant who could draw the figure well, and being, like Lawrence, deficient in all but the head, found out the ingenious painter of clock-faces, and engaged him at the moderate salary of forty pounds a year, with an especial injunction to secrecy. In this capacity he worked upon a picture of Garrick and Miss Bellamy in “Romeo and Juliet,” which was exhibited under the name of Wilson. Garrick’s keen eye satisfied him that another hand was in the work; so he resolved to discover the unknown painter. This discovery he effected by perseverance: he made the acquaintance of Zoffany and became his patron, employing him himself and introducing him to his friends; and in this way his bias to theatrical portraiture became established. Garrick’s favour met with an ample return in the admirable portraits of himself and contemporaries, which have rendered their personal appearance so speakingly familiar to posterity both in his pictures and the admirable mezzotinto scrapings of Earlom. Zoffany was elected among the first members of the Royal Academy in 1768.

The old Cockpit, or Phœnix Theatre, stood on the site of what is now called Pitt Place. Early in James I.’s reign it had been turned into a playhouse, and probably rebuilt.[553]

On Shrove Tuesday 1616-17 the London prentices, roused to their annual zeal by a love of mischief and probably a Puritan fervour, sacked the building, to the discomfiture of the harmless players. Bitter, narrow-headed Prynne, who notes with horror and anger the forty thousand plays printed in two years for the five Devil’s chapels in London,[554] describes the Cockpit as demoralising Drury Lane, then no doubt wealthy, and therefore supposed to be respectable. In 1647 the Cockpit Theatre was turned into a schoolroom; in 1649 Puritan soldiers broke into the[Pg 305] house, which had again become a theatre, captured the actors, dispersed the audience, broke up the seats and stage, and carried off the dramatic criminals in open day, in all their stage finery, to the Gate House at Westminster.

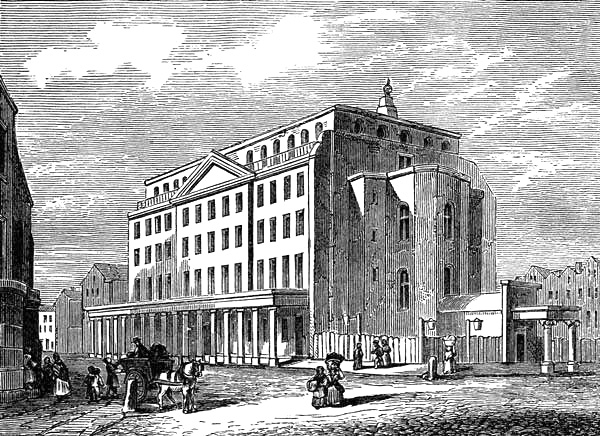

Rhodes, the old prompter at Blackfriars, who had turned bookseller, reopened the Cockpit on the Restoration. The new Theatre in Drury Lane opened in 1663 with the “Humorous Lieutenant” of Beaumont and Fletcher. This was the King’s Company under Killigrew. Davenant and the Duke of York’s company found a home first in the Cockpit, and afterwards in Salisbury Court, Fleet Street.

The first Drury Lane Theatre was burnt down in 1672. Wren built the new house, which opened in 1674 with a prologue by Dryden. Cibber gives a careful account of Wren’s Drury Lane, the chief entrance to which was down Playhouse Passage. Pepys blamed it for the distance of the stage from the boxes, and for the narrowness of the pit entrances.[555] The platform of the stage projected very forward, and the lower doors of entrance for the actors were in the place of the stage-boxes.[556]

In 1681 the two companies united, leaving Portugal Street to the lithe tennis-players and Dorset Gardens to the brawny wrestlers. Wren’s theatre was taken down in 1791; its successor, built by Holland, was opened in 1794, and destroyed in 1809. The present edifice, the fourth in succession, is the work of Wyatt, and was opened in 1812.[557]

Hart, Mohun, Burt, and Clun were all actors in Killigrew’s company. Hart, who had been a captain in the army, was dignified as Alexander, incomparable as Catiline, and excellent as Othello. He died in 1683. Mohun, whom Nat Lee wrote parts for, and who had been a major in the Civil War, was much applauded in heroic parts, and was a favourite of Rochester’s. Burt played Cicero in Ben Jonson’s “Catiline;” and poor Clun, who was murdered by footpads in Kentish Town, was great as Iago, and as Subtle in “The Alchymist.”

[Pg 306]From Pepys’s memoranda of visits to Drury Lane we gather a few facts about the licentious theatre-goers of his day. After the Plague, when Drury Lane had been deserted, the old gossip went there, half-ashamed to be seen, and with his cloak thrown up round his face.[558] The king flaunts about with his mistresses, and Pepys goes into an upper box to chat with the actresses and see a rehearsal, which seems then to have followed and not preceded the daily performance.[559] He describes Sir Charles Sedley, in the pit, exchanging banter with a lady in a mask. Three o’clock seems to have been about the time for theatres opening.[560] The king was angry, he says, with Ned Howard for writing a play called “The Change of Crowns,” in which Lacy acted a country gentleman who is astonished at the corruption of the court. For this Lacy was committed to the porter’s lodge; on being released, he called the author a fool, and having a glove thrown in his face, returned the compliment with a blow on Howard’s pate with a cane; upon which the pit wondered that Howard did not run the mean fellow through; and the king closed the house, which the gentry thought had grown too insolent.

August 15, 1667, Pepys goes to see the “Merry Wives of Windsor,” which pleased our great Admiralty official “in no part of it.” Two days after he weeps at the troubles of Queen Elizabeth, but revives when that dangerous Mrs. Knipp dances among the milkmaids, and comes out in her nightgown to sing a song. Another day he goes at three o’clock to see Beaumont and Fletcher’s “Scornful Lady,” but does not remain, as there is no one in the pit. In September of the same year he finds his wife and servant in an eighteenpenny seat. In October 1667 he ventures into the tiring-room where Nell was dressing, and then had fruit in the scene-room, and heard Mrs. Knipp read her part in “Flora’s Vagaries,” Nell cursing because there were so few people in the pit. A fortnight after he contrives to see a new play, “The Black Prince,” by Lord Orrery; and though he goes at two, finds no room in the pit, and has[Pg 307] for the first time in his life to take an upper four-shilling-box. November 1, he proclaims the “Taming of the Shrew” “a silly old play.” November 2, the house was full of Parliament men, the House being up. One of them choking himself while eating some fruit, Orange Moll thrust her finger down his throat and brought him to life again.

Pepys condemns Nell Gwynn as unbearable in serious parts, but considers her beyond imitation as a madwoman. In December 1667 he describes a poor woman who had lent her child to the actors, but hearing him cry, forced her way on to the stage and bore it off from Hart.

It would seem from subsequent notes in the Diary, that to a man who stopped only for one act at a theatre, and took no seat, no charge was made.

In February 1668 Pepys sees at Drury Lane “The Virgin Martyr,” by Massinger, which he pronounces not to be worth much but for Becky Marshall’s acting; yet the wind music when the angel descended “wrapped up” his soul so, that, remarkably enough, it made him as sick as when he was first in love, and he determined to go home and make his wife learn wind music. May 1, 1668, he mentions that the pit was thrown into disorder by the rain coming in at the cupola. May 7 of the same year, he calls for Knipp when the play is over, and sees “Nell in her boy’s clothes, mighty pretty.” “But, Lord!” he says, “their confidence! and how many men do hover about them as soon as they come off the stage! and how confident they are in their talk!”

On May 18, 1668, Pepys goes as early as twelve o’clock to see the first performance of that poor play, Sir Charles Sedley’s “Mulberry Garden,” at which the king, queen, and court did not laugh. While waiting for the curtain to pull up, Pepys hires a boy to keep his place, slips out to the Rose Tavern in Russell Street, and dines off a breast of mutton from the spit.

On September 15, 1668, there is a play—“The Ladies à la Mode”—so bad that the actor who announced the piece to be repeated fell a-laughing, as did the pit. Four[Pg 308] days after Pepys sits next Shadwell, the poet, admiring Ben Jonson’s extravagant comedy, “The Silent Woman.”

In January 1669 he sat in a box near “that merry jade Nell,” who, with a comrade from the Duke’s House, “lay there laughing upon people.”

“Les Horaces” of Corneille he found “a silly tragedy.” February 1669 Beetson, one of the actors, read his part, Kynaston having been beaten and disabled by order of Sir Charles Sedley, whom he had ridiculed. The same month Pepys went to the King’s House to see “The Faithful Shepherdess,” and found not more than £10 in the house.

A great leader in the Drury Lane troop was Lacy, the Falstaff of his day. He was a handsome, audacious fellow, who delighted the town as “Frenchman, Scot, or Irishman, fine gentleman or fool, honest simpleton or rogue, Tartuffe or Drench, old man or loquacious woman.” He was King Charles’s favourite actor as Teague in “The Committee,” or mimicking Dryden as Bayes in “The Rehearsal.”

The greatest rascal in the company was Goodman—“Scum Goodman,” as he was called—admirable as Alexander and Julius Cæsar. He was a dashing, shameless, impudent rogue, who used to boast that he had once taken “an airing” on the road to recruit his purse. He was expelled Cambridge for slashing a picture of the Duke of Monmouth. He hired an Italian quack to poison two children of his mistress, the infamous Duchess of Cleveland, joined in the Fenwick plot to kill King William, and would have turned traitor against his fellow conspirators had he not been bought off for £500 a year, and sent to Paris, where he disappeared.

Haines, one of Killigrew’s band, was an impudent but clever low comedian. In Sparkish, in “The Country Wife,” he was the very model of airy gentlemen. His great successes were as Captain Bluff in Congreve’s “Old Bachelor,” Roger in “Æsop,” and “the lively, impudent, and irresistible Tom Errand” in Farquhar’s “Constant Couple,” “that most triumphant comedy of a whole century.”[561]

[Pg 309]The stories told of Joe Haines are good. He once engaged a simple-minded clergyman as “chaplain to the Theatre Royal,” and sent him behind the scenes ringing a big bell to call the actors to prayers. “Count” Haines was once arrested by two bailiffs on Holborn Hill at the very moment that the Bishop of Ely passed in his carriage. “Here comes my cousin, he will satisfy you,” said the ready-witted actor, who instantly stepped to the carriage window and whispered Bishop Patrick—“Here are two Romanists, my lord, inclined to become Protestants, but yet with some scruples of conscience.” The anxious bishop instantly beckoned to the bailiffs to follow him to Ely Place, and Joe escaped; the mortified bishop paying the money out of sheer shame. Haines died in 1701.

Amongst the actresses at this house were pretty but frail Mrs. Hughes, the mistress of Prince Rupert, and Mrs. Knipp, Pepys’s dangerous friend, who acted rakish fine ladies and rattling ladies’-maids, and came on to sing as priestess, nun, or milkmaid. Anne Marshall, the daughter of a Presbyterian divine, acquired a reputation as Dorothea in “The Virgin Martyr,” and as the Queen of Sicily in Dryden’s “Secret Love.”

But Nell Gwynn was the chief “toast” of the town. Little, pretty, impudent, and witty, she danced well, and was a good actress in comedy and in characters where “natural emotion bordering on insanity” was to be represented.[562] Her last original part was that of Almahide in Dryden’s “Conquest of Granada,” where she spoke the prologue in a straw hat as large as a waggon-wheel.

Leigh Hunt says that “Nineteen out of twenty of Dryden’s plays were produced at Drury Lane, and seven out of Lee’s eleven; all the good plays of Wycherly, except ‘The Gentleman Dancing Master;’ two of Congreve’s—‘The Old Bachelor’ and ‘The Double Dealer;’ and all Farquhar’s, except ‘The Beau’s Stratagem.’”[563] Dryden’s impurity and daring bombast were the attractions to Drury Lane, as Otway’s sentimentalism and real pathos were to the[Pg 310] rival house. Lee’s splendid bombast was succeeded by Farquhar’s gay rakes and not too virtuous women.

Doggett, who was before the public from 1691 to 1713, was a little lively Irishman, for whom Congreve wrote the characters of Fondlewife, Sir Paul Pliant, and Ben. He was partner in the theatre with Cibber and Wilkes from 1709 to 1712, but left when Booth was taken into the firm. He was a staunch Whig, and left an orange livery and a badge to be rowed for yearly by six London watermen.

The queen of comedy, Mrs. Oldfield, flashed upon the town first as Lady Betty Modish in Cibber’s “Careless Husband,” in 1704-5. When quite a girl she was overheard by Farquhar reading “The Scornful Lady” of Beaumont and Fletcher to her aunt, who kept the Mitre Tavern in St. James’s Market. Farquhar introduced her to Vanbrugh, and Vanbrugh to Rich. “She excelled all actresses,” says Davies, “in sprightliness of wit and elegance of manner, and was greatly superior in the clear, sonorous, and harmonious tones of her voice.” Her eyes were large and speaking, and when intended to give special archness to some brilliant or gay thought, she kept them mischievously half shut. Cibber praises Mrs. Oldfield for her unpresuming modesty, and her good sense in not rejecting advice—“A mark of good sense,” says the shrewd old manager, “rarely known in any actor of either sex but herself. Yet it was a hard matter to give her any hint that she was not able to take or improve.”[564] With all this merit, she was tractable and less presuming in her station than several that had not half her pretensions to be troublesome. This excellent actress was not fond of tragedy, but she still played Marcia in “Cato;” Swift, who attended the rehearsals with Addison, railed at her for her good-humoured carelessness and indifference; and Pope sneered at her vanity in her last moments. It is true that she was buried in kid gloves, tucker, and ruffles of best lace. Mrs. Oldfield lived first with a Mr. Maynwaring, a rough, hard-drinking Whig writer, to whom Addison dedicated one of the volumes of the Spectator; and after[Pg 311] his death with General Churchill, one of the Marlborough family. Nevertheless, she went to court and habitually associated with ladies of the highest rank. Society is cruel and inconsistent in these matters. Open scandal it detests, but to secret vice it is indifferent.

Mrs. Oldfield died in 1730, lay in state in the Jerusalem Chamber, and when she was borne to her grave in the Abbey, Lord Hervey (Pope’s “Sporus”), Lord Delawarr, and that toady Bubb Doddington, supported her pall. The late Earl of Cadogan was the great-grandson of Anne Oldfield.[565] This actress, so majestic in tragedy, so irresistible in comedy, was generous enough to give an annuity to poor, hopeless, scampish Savage.

Robert Wilkes, a young Irish Government clerk, obtained great successes as Farquhar’s heroes, Sir Harry Wildair, Mirabel, Captain Plume, and Archer. He played equally well the light gentlemen of Cibber’s comedies. Genest describes him as buoyant and graceful on the stage, irreproachable in dress, his every movement marked by “an ease of breeding and manner.” This actor also excelled in plaintive and tender parts. Cibber hints, however, at his professional conceit and overbearing temper. Wilkes on one occasion read “George Barnwell” to Queen Anne at the Court at St. James’s. He died in 1732.

Barton Booth, who was at Westminster School with Rowe the poet, identified himself with Addison’s Cato. His dignity, pathos, and energy as that lover of liberty led Bolingbroke to present him on the first night with a purse of fifty guineas. The play was translated into four languages; Pope gave it a prologue; Garth decked it with an epilogue; while Denis proved it, to his own satisfaction, to be worthless. Aaron Hill tells us that statistics proved that Booth could always obtain from eighteen to twenty rounds of applause during the evening. When playing the Ghost to Betterton’s Hamlet, Booth is said to have been once so horror-stricken as to be unable to proceed with his part. He often took inferior Shaksperean parts, and was[Pg 312] frequently indolent; but if he saw a man whose opinion he valued among the audience he fired up and played to him. This petted actor and manager died in 1733.

Colley Cibber, to judge from Steele’s criticisms, must have been admirable as a beau, whether rallying pleasantly, scorning artfully, ridiculing, or neglecting.[566] Wilkes surpassed him in beseeching gracefully, approaching respectfully, pitying, mourning, and loving. In the part of Sir Fopling Flutter in “The Fool of Fashion,” played in 1695, Cibber wore a fair, full-bottomed periwig which was so much admired that it used to be brought on the stage in a sedan and put on publicly. To this wonder of the town Colonel Brett, who married Savage’s mother, took a special fancy. “The beaux of those days,” says Cibber, “had more of the stateliness of the peacock than the pert of the lapwing.” The colonel came behind the scenes, first praised the wig, and then offered to purchase it. On Cibber’s bantering him about his anxiety for such a trifle, the gay colonel began to rally himself with such humour that he fairly won Cibber, and they sat down at once, laughing, to finish their bargain over a bottle.

Quin’s career began at Dublin in 1714, and ended at Bath in 1753. From 1736 to 1741 he was at Drury Lane. From Booth’s retirement till the coming of Garrick, Quin had no rival as Cato, Brutus, Volpone, Falstaff, Zanga, etc. His Macbeth, Othello, and Lear were inferior. Davies says, the tender and the violent were beyond his reach, but he gave words weight and dignity by his sensible elocution and well-regulated voice. His movements were ponderous and his action languid. Quin was generous, witty, a great epicure, and a careless dresser. It was his hard fate, though a warm-hearted man, to be equally warm in temper, and to kill two adversaries in duels that were forced upon him. Quin was a friend of Garrick and of Thomson the poet, and a frequent visitor at Allen’s house at Prior Park, near Bath, where Pope, Warburton, and Fielding visited.

Some of Quin’s jests were perfect. When Warburton[Pg 313] said, “By what law can the execution of Charles I. be justified?” Quin replied, “By all the laws he had left them.” No wonder Walpole applauded him. The bishop bade the player remember that the regicides came to violent ends, but Quin gave him a worse blow. “That, your lordship,” he said, “if I am not mistaken, was also the case with the twelve apostles.” Quin could overthrow even Foote. They had at one time had a quarrel, and were reconciled, but Foote was still a little sore. “Jemmy,” said he, “you should not have said that I had but one shirt, and that I lay in bed while it was washed.” “Sammy,” replied the actor, “I never could have said so, for I never knew that you had a shirt to wash.” Quin died in 1766, and Garrick wrote an epitaph on his tomb in Bath Abbey, ending with the line—

“To this complexion we must come at last.”

Garrick appeared first at Goodman’s Fields Theatre, in 1741, as King Richard. In eight days the west flocked eastward, and, as Davies tells us, “the coaches of the nobility filled up the space from Temple Bar to Whitechapel.” Pope came up from Twickenham to see if the young man was equal to Betterton. Garrick revolutionised the stage. Tragedians had fallen into a pompous “rhythmical, mechanical sing-song,”[567] fit only for dull orators. Their style was overlaboured with art—it was mere declamation. The actor had long ceased to imitate nature. Garrick’s first appearance at Drury Lane was in 1742. Cumberland, then at Westminster School, describes his sight of Quin and Garrick, and the first impressions they produced on him. Garrick was Lothario, Mrs. Cibber Calista, Quin Horatio, and Mrs. Pritchard Lavinia. Quin, when the curtain drew up, presented himself in a green velvet coat, embroidered down the seams, an enormous full-bottomed periwig, rolled stockings, and high-heeled square shoes.[568] “With very little variation of cadence, and in a deep full tone, accompanied by a sawing kind of action which had[Pg 314] more of the senate than the stage in it, he rolled out his heroics with an air of dignified indifference that seemed to disdain the plaudits that were bestowed upon him. Mrs. Cibber, in a key high-pitched but sweet withal, sang or rather recitatived Rowe’s harmonious strains. But when, after long and anxious expectation, I first beheld little Garrick, then young and light and alive in every muscle and every feature, come bounding on the stage and pointing at the wittol Altamont and heavy-paced Horatio, heavens! what a transition!—it seemed as if a whole century had been swept over in the passage of a single scene.” And yet, according to fretful Cumberland, “the show of hands” was for Quin, though, according to Davies, the best judges were for Garrick. And when Quin was slow in answering the challenge, somebody in the gallery called out, “Why don’t you tell the gentleman whether you will meet him or not?” Garrick’s repertory extended to one hundred characters, of which he was the original representative of thirty-six. Of his comic characters, Ranger and Abel Drugger were the best—one was irresistibly vivacious, the other comically stupid.

Garrick, who mutilated Shakespere and wrote clever verses and useful theatrical adaptations, was a vain, sprightly man, who got the reputation of reforming stage costume, although it was Macklin, pugnacious and courageous, who first dared to act Macbeth dressed as a Highland chief, and felt proud of his own anachronism. Garrick had, in fact, a dislike to really truthful costume. He dared to play Hotspur in laced frock and Ramillies wig.[569] In truth, it was neither Garrick nor Macklin who originated this reform, but the change of public opinion and the widening of education. West, in spite of ridicule and condemnation, dared to dress the soldiers in his “Death of Wolfe” in English uniform, instead of in the armour of stage Romans. Burke said of Garrick that he was the most acute observer of nature he had ever known. Garrick could assume any passion at the moment, and could act off-hand Scrub or Richard, Brute[Pg 315] or Macbeth. He oscillated between tragedy and comedy; he danced to perfection; he was laborious at rehearsals, and yet all that he did seemed spontaneous. In Fribble he imitated no fewer than eleven men of fashion so that every one recognised them. Garrick died in 1779, and was buried in the Abbey. “Chatham,” says Dr. Doran, the actor’s admirable biographer, “had addressed him living in verse, and peers sought for the honour of supporting the pall at his funeral.”[570] That he was vain and over-sensitive there can be no doubt; but there can be also no doubt that he was generous, often charitable, delightful in society, and never, like Foote, eager to give pain by the exercise of his talent. As an actor, Garrick has not since been equalled in versatility and equal balance of power; nor has any subsequent actor attained so high a rank among the intellect of his age.

Kitty Clive, born in 1711, took leave of the stage in 1769. She was one of the best-natured, wittiest, happiest, and most versatile of actresses, whether as “roguish chambermaid, fierce virago, chuckling hoyden, brazen romp, stolid country girl, affected fine lady, or thoroughly natural old woman.”[571] Fielding, Garrick, and Walpole delighted in Kitty Clive. After years of quadrille at Purcell’s, and cards and music at the villa at Teddington which Horace Walpole lent her, Kitty Clive died suddenly, without a groan, in 1785.

Woodward was excellent in fops, rascals, simpletons, and Shakesperean light characters. His Bobadil, Marplot, and Touchstone were beyond approach. Shuter, originally a billiard-marker, came on the stage in 1744, and quitted it in 1776. His grimace and impromptu were much praised.

Samuel Foote, born at Truro in 1720, having failed in tragedy, and not been very successful in comedy, started his entertainments at the Haymarket in 1747. He died in 1777. His history belongs to the records of another theatre.

Spanger Barry in 1748-9 acted Hamlet and Macbeth alternately with Garrick. Davies says that Barry could not[Pg 316] perform such characters as Richard and Macbeth, but he made a capital Alexander. “He charmed the ladies by the soft melody of his love complaints and the noble ardour of his courtship.” Only Mrs. Cibber excelled him in the expression of love, grief, tenderness, and jealous rage. Tall, handsome, and dignified, Barry undoubtedly ran Garrick close in the part of Romeo, artificial as Churchill in the Rosciad declares him to have been. A lady once said, “that had she been Juliet she should have expected Garrick to have stormed the balcony, he was so impassioned; but that Barry was so eloquent, tender, and seductive, that she should have come down to him.”[572] In Lear, the town said that Barry “was every inch a king” but Garrick “every inch King Lear.” Barry was amorous and extravagant. He delighted in giving magnificent entertainments, and treated Mr. Pelham in so princely a style that that minister (with not the finest taste) rebuked him for his lavish hospitality.

The brilliant and witching Peg Woffington was the daughter of a small huckster in Dublin, and became a pupil of Madame Violante, a rope-dancer. In 1740 she came out at Covent Garden, and soon won the town as Sir Harry Wildair. She played Lady Townley and Lady Betty Modish with “happy ease and gaiety.”[573] She rendered the most audacious absurdities pleasing by her beautiful bright face and her vivacity of expression. Peg quarrelled with Kitty Clive and Mrs. Cibber, and detested that reckless woman George Anne Bellamy. This witty and enchanting actress, as generous and charitable as Nell Gwynn with all her faults, was struck by paralysis while acting Rosalind at Covent Garden, and died in 1760.

During his career from 1691 to his retirement in 1733, clever, careless Colley Cibber originated nearly eighty characters, chiefly grand old fops, inane old men, dashing soldiers, and impudent lacqueys. His Fondlewife, Sir Courtly Nice, and Shallow were his best parts. “Of all English managers,” says Dr. Doran, “Cibber was the most successful. Of the English actors, he is the only one who[Pg 317] was ever promoted to the laureateship or elected a member of White’s Club.” Even Pope, who hated him and got some hard blows from him, praised “The Careless Husband;” Walpole, who despised players, praised Colley; and Dr. Johnson approved of his admirably written Apology.

Cibber’s daughter, Mrs. Clarke, led a wild and disreputable life, became a waitress at Marylebone, and died in poverty in 1760. Colley’s son Theophilus, the best Pistol ever seen on the stage, and the original George Barnwell, was drowned in crossing the Irish Sea.

His wife was a sister of Dr. Arne, the composer. In tragedy she was remarkable for her artless sensibility and exquisite variety of expression. As Ophelia she moved even Tate Wilkinson. She was one of the first actresses to make the woes of the grand tragedy queen natural. She died in 1766, and was buried in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey.

Mrs. Pritchard, that “inspired idiot,” as Dr. Johnson called her in his contempt for her ignorance, seems to have been a virtuous woman. She left the stage in 1768. Though plain, and in later years very stout, Mrs. Pritchard was admired in tragedy for her perfect pronunciation and her force and dignity as the Queen in “Hamlet,” and as Lady Macbeth. She was also a good comedian in playful and witty parts. She was, however, not very graceful, and inclined to rant.

When Mrs. Cibber died in 1765, Mrs. Yates succeeded to her fame, with Mrs. Barry for a rival, till Mrs. Siddons came from Bath and unseated both. Mrs. Yates was wanting in pathos, but in pride and scorn as Medea, or in hopeless grief as Constance, she was unapproachable. She died in 1787.

George Anne Bellamy, the reckless and the unfortunate, was the daughter of a Quakeress, with whom Lord Tyrawley ran away from school. Dr. Doran says, “What with the loves, caprices, charms, extravagances, and sufferings of Mrs. Bellamy, she excited the wonder, admiration, pity, and contempt of the town for thirty years.”[574] Now she was[Pg 318] squandering money like a Cleopatra; now she was crouching on the wet steps of Westminster Bridge, brooding over suicide. “The Bellamy,” says the critic, was only equal to “the Cibber” in expressing the ecstasy of love. This follower of the old school of intoners was the original Volumnia of Thomson, the Erixene of Dr. Young, and the Cleone of the honest footman poet and publisher Dodsley. She took her farewell benefit in 1784.

In 1778 Miss Farren appeared at Drury Lane. She was the daughter of a poor vagabond strolling player. Walpole says she was the most perfect actress he had ever seen; and he spoke well of her fine ladies, of whom he was a judge. Adolphus, not easily appeased, praised her irresistible graces and “all the indescribable little charms which give fascination to the women of birth and fashion.” She was gay as Lady Betty Modish, sentimental as Cecilia or Indiana, and playful as Rosara in the “Barber of Seville.” In 1797 the little girl who had been helped over the ice to the lock-up at Salisbury, to hand up a bowl of milk to her father when a prisoner there,[575] took leave of the stage in the part of Lady Teazle, and married the Earl of Derby, who had buried his wife just six weeks before.

In 1798 Mrs. Abington, “the best affected fine lady of her time,” retired from the stage of Drury Lane. She was the daughter of a common soldier, and as a girl was known as “Nosegay Fan,” and had sold flowers in St. James’s Park. She first appeared at Drury Lane in 1756-7.

Poor Mrs. Robinson, the “Perdita” so heartlessly betrayed by the Prince of Wales, was driven on to the stage in 1776 by her husband, a handsome scapegrace who had run through his fortune. She passed from the stage in 1780, and died, forgotten, poor, and paralytic, in 1800.

In 1767 Samuel Reddish, Canning’s stepfather, first appeared at Drury Lane as Lord Townley. He was a reasonably good Edgar and Posthumus, but failed in parts of passion. He went mad in 1779. In this group of minor actors we may include Gentleman Smith, a good Charles[Pg 319] Surface, who retired from the stage in 1786; Yates, whose forte was old men and Shakspere’s fools (1736-1780); Dodd, who, from 1765 to 1796, was the prince of fops and old men (Master Slender and Master Stephen were said to die with him); and lastly, that great comic actor, John Palmer, who died on the stage in 1798, as he was playing the Stranger. He was the original representative of plausible Joseph Surface. “Plausible,” he used to say, “am I? You rate me too highly. The utmost I ever did in that way was that I once persuaded a bailiff who had arrested me to bail me.” Once when making friends with Sheridan after a quarrel, Palmer said to the author, “If you could but see my heart, Mr. Sheridan!” to which Sheridan replied, “Why, Jack, you forgot I wrote it.” “Jack Palmer,” says Lamb, “was a gentleman with a slight infusion of the footman.”[576] He had two voices, both plausible, hypocritical, and insinuating.

Henderson was engaged by Sheridan for Drury Lane in 1777. As Falstaff this humorous friend of Gainsborough was seldom equalled. His defects were a woolly voice and a habit of sawing the air. Dr. Doran says, “he was the first actor who, with Sheridan, gave public readings” at Freemasons’ Hall; and his recitation of “John Gilpin” gave impetus to the sale of the narrative of that adventurous ride.[577] Henderson died in 1785, aged only thirty-eight, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Mrs. Siddons, the daughter of an itinerant actor, was born in 1755. After strolling and becoming a lady’s-maid, she married a poor second-rate actor of Birmingham. She appeared first at Drury Lane in 1775 as Portia. Her first real triumph was in 1780, as Isabella in Southerne’s tragedy. The management gave her Garrick’s dressing-room, and some legal admirers presented her with a purse of a hundred guineas. Soon afterwards, as Jane Shore, she sent many ladies in the audience into fainting fits. This great actress closed her career in 1812 with Lady Macbeth, her greatest triumph. She is said to have made King George III. shed[Pg 320] tears. He admired her especially for her repose. “Garrick,” he used to say, “could never stand still. He was a great fidget.” No actress received more homage in her time than Mrs. Siddons. Reynolds painted his name on the hem of her garment in his portrait of her as the Tragic Muse. Dr. Johnson kissed her hand and admired her genius. In comedy Mrs. Siddons failed; her rigorous Grecian face was not arch. “In comedy” says Colman, “she was only a frisking grig.” “Those who knew her best,” says Dr. Doran, “have recorded her grace, her noble carriage, divine elocution and solemn earnestness, her grandeur, her pathos, her correct judgment.” Erskine studied her cadences and tones. According to Campbell, she increased the heart’s capacity for tender, intense, and lofty feelings. This lofty-minded actress, as Young calls her, died in 1831.

Her elder brother, John Kemble, first appeared at Drury Lane, in 1783, as Hamlet. In 1788-9 he succeeded King as manager of the theatre, and continued so till 1801. In Coriolanus and Cato, Kemble was pre-eminent, but his Richard and Sir Giles were inferior to Cook’s and Kean’s. In comedy he failed, except in snatches of dignity or pathos. As an actor Kemble was sometimes heavy and monotonous. He had not the fire or versatility of Garrick, or the wild passion of Edmund Kean. As Hamlet he was romantic, dignified, and philosophic. In his Rolla he delighted Sheridan and Pitt; in Octavian he drew tears from all eyes. He excelled also in Cœur de Lion, Penruddock, and the Stranger. In private life he was always majestic and gravely convivial. When Covent Garden was burnt down in 1808, he bore the loss bravely, and on the night of the opening the generous Duke of Northumberland sent him back his bond for £10,000 to be committed to the flames. Walpole, who saw Kemble, preferred him to Garrick in Benedick, and to Quin in Maskwell. Kemble took his solemn farewell of the stage in 1817 as Coriolanus, and died at Lausanne in 1823. Leigh Hunt, an excellent dramatic critic, paints the following picture of Kemble: “A figure of melancholy dignity, dealing out a most measured speech in sepulchral[Pg 321] tones and a pedantic pronunciation, and injuring what he has made you feel by the want of feeling it himself.”[578] John Kemble’s brother Charles acted well in Mercutio, Young Mirabel, and Benedick. He remained on the stage till 1836.

George Frederick Cooke, whose life was one perpetual debauch, and whose career on the stage extended from 1801 to 1812, when he died at Boston, did not, I think, appear at Drury Lane. His laurels were won chiefly at Covent Garden.

Master Betty, born in 1791 at Shrewsbury, elegant, and quick of memory, appeared at Drury Lane in 1804, fretted his little hour upon the stage, and earned a fortune with which he prudently retired in 1808. He lived till 1876.

King, the original representative of Sir Peter Teazle, Lord Ogleby, Puff, and Dr. Cantwell, began his London career at Drury Lane in 1748. He left the stage in 1802. His best characters were Touchstone and Ranger, and in these parts he was always arch, rapid, and versatile. Hazlitt discourses on King’s old, hard, rough face, and his shrewd hints and tart replies.

Dickey Suett was a favourite low comedian from 1780 to 1805, when he died. He was a tall, thin, ungainly man, too much addicted to grimace, interpolations, and practical jokes. He drank hard, and suffered from mental depression. Hazlitt calls him “the delightful old croaker, the everlasting Dickey Gossip of the stage.”[579] Lamb describes his “Oh, la!” as irresistible; “he drolled upon the stock of those two syllables richer than the cuckoo.” Shakspere’s jesters “have all the true Suett stamp—a loose and shambling gait, and a slippery tongue.”[580]

Miss Pope, who left the stage in 1808, had played with Garrick and Mrs. Clive. She was the original Polly Honeycomb, Miss Sterling, Mrs. Candour, and Tilburina. In youth she played hoydens, chambermaids, and half-bred ladies, with a dash and good-humour free from all vulgarity,[Pg 322] and in old age she took to duennas and Mrs. Heidelburg. In 1761 Churchill mentions her as “lively Pope,” and in 1807 Horace Smith describes her as “a bulky person with a duplicity of chin.”

In 1741 the theatre, which had been rebuilt by Wren in 1674, in a cheap and plain manner, became ruinous, and was enlarged and almost rebuilt by the Adams. In 1747 Garrick became the manager, and Dr. Johnson, as a friend, wrote the celebrated address beginning with the often-quoted lines—

“When Learning’s triumph o’er her barbarous foes

First reared the stage, immortal Shakspere rose.

******

Each change of many-coloured life he drew,

Exhausted worlds, and then imagined new;

Existence saw him spurn her bounded reign,

And panting Time toiled after him in vain.”

In 1775, the year in which “The Duenna” was brought out at Covent Garden, Garrick made known his wish to sell a moiety of the patent of this theatre. In June 1776 a contract was signed, Mr. Sheridan taking two-fourteenths of the whole for £10,000, Mr. Linley the same, and Dr. Ford three-fourteenths at £15,000.[581] How Sheridan raised the money no one ever knew.

Sheridan’s first contribution to this new stage was an alteration of Vanbrugh’s licentious comedy of “The Relapse,” which he called “A Trip to Scarborough,” and brought out in 1777. The same year the brilliant manager, then only six-and-twenty, produced the finest and most popular comedy in the English language, “The School for Scandal.” On the last slip of this miracle of wit and dramatic construction Sheridan wrote—“Finished at last, thank God!—R. B. Sheridan.” Below this the prompter added his devout response—“Amen.—W. Hopkins.”[582] Garrick was proud of the new manager, and boasted of his budding genius.[583]

[Pg 323]In 1778 Sheridan bought out Mr. Lacy for more than £45,000, and Dr. Ford for £77,000. In 1779 Garrick died, and Sheridan wrote a monody to his memory, which was delivered by Mrs. Yates after the play of “The West Indian.” Slander attributed the finest passage in this monody to Tickell, just as it had before attributed Tickell’s bad farce to Sheridan.

Dowton, who appeared in 1796 as Sheva, was felicitous in good-natured testy old men, and also in crabbed and degraded old villains. His Dr. Cantwell and Sir Anthony Absolute were in the true spirit of old comedy. Leigh Hunt praises Dowton’s changes from the irritable to the yielding, and from the angry to the tender.

Willy Blanchard was natural and unaffected, but mannered.

Mathews first appeared in London in 1803. He excelled in valets and old men, and drew tears as M. Mallet, the poor emigré who is disappointed about a letter.

Liston made his début at the Haymarket in 1805 as Sheepface. Leigh Hunt praises his ignorant rustics, and condemns his old men. He sets him down as a painter of emotions, and therefore more intellectual than Fawcett and less farcical than Munden. Liston was a hypochondriac; below his fun there was always an under-current of melancholy, “as though,” says Dr. Doran, mysteriously, “he had killed a boy when, under the name of Williams, he was usher at the Rev. Dr. Burney’s at Gosport.”[584]

In 1807 Jones and Young made their first appearances, but not at Drury Lane. Young originated Rienzi, and played Hamlet, Falstaff, and Captain Macheath. Jones was a stage rake of great excellence.

Among the actresses before Kean, we may mention Miss Brunton, afterwards Countess of Craven, and Mrs. Davison, a good Lady Teazle.

Lewis, who left the stage in 1809, was a draper’s son. He died in 1813, and out of part of his fortune the new church at Ealing was erected. He played Young Rapid[Pg 324] and Jeremy Diddler, and created the Hon. Tom Shuffleton in “John Bull.” His restless style suited Morton and Reynolds’s comedies, and he succeeded in “all that was frolic, gay, humorous, whimsical, eccentric, and yet elegant.” He was manager of Covent Garden for twenty-one years, and made everyone do his duty by kindness and good treatment. Leigh Hunt sketches Lewis admirably, with his “easy flutter,”[585] short knowing respiration, and complacent liveliness. Lewis played the gentleman with more heart than Elliston. He seemed polite, not from vanity, but rather from a natural irresistible wish to please. He had all the laborious carelessness of action, important indifference of voice, and natural vacuity of look that are requisite for the lounger.[586] His defects were a habit of shaking his head and drawing in of the breath. His “flippant airiness,” “vivacious importance,” and “French flutter” must have been in their way perfect. “Gay, fluttering, hair-brained Lewis!” says Hazlitt; “nobody could break open a door, or jump over a table, or scale a ladder, or twirl a cocked hat, or dangle a cane, or play a jockey-nobleman or a nobleman’s jockey like him.”[587]

Here a moment’s pause for an anecdote. When a riot took place at Drury Lane in 1740 about the non-appearance of a French dancer, the first symptoms of the outbreak were the ushering of ladies out of the pit. A noble marquis gallantly proposed to fire the house. The proposal was considered, but not adopted. The bucks and bloods then proceeded to destroy the musical instruments and fittings, to break the panels and partitions, and pull down the royal arms. The offence was finally condoned by the ringleading marquis sending £100 to the manager.

Charles Lamb describes Drury Lane in his own delightful way. The first play he ever saw was in 1781-2, when he was six years old. “A portal, now the entrance,” he writes, “to a printing-office, at the north end of Cross Court was the pit entrance to old Drury; and I never pass it without[Pg 325] shaking some forty years from off my shoulders, recurring to the evening when I passed through it to see my first play. The afternoon was wet: with what a beating heart did I watch from the window the puddles!

“It was the custom then to cry, ‘’Chase some oranges, ’chase some nonpareils, ’chase a bill of the play?’ But when we got in, and I beheld the green curtain that veiled a heaven to my imagination, the breathless anticipations I endured! The boxes, full of well-dressed women of quality, projected over the pit. The orchestra lights arose—the bell sounded once—it rang the second time—the curtain drew up, and the play was ‘Artaxerxes;’ ‘Harlequin’s Invasion’ followed.”

The next play Lamb went to was “The Lady of the Manor,” followed by a pantomime called “Lunn’s Ghost.” Rich was not long dead. His third play was “The Way of the World” and “Robinson Crusoe.” Six or seven years after he went (with what changed feelings!) to see Mrs. Siddons in Isabella. “Comparison and retrospection,” he says, “soon yielded to the present attraction of the scene, and the theatre became to me, upon a new stock, the most delightful of all recreations.”[588]

Handsome Jack Bannister, who played in youth with Garrick, and in later years with Edmund Kean, was the model for the Uncle Toby in Leslie’s picture. Natural, honest, as Hamlet, he was also good as Walter in “The Children of the Wood.” Inimitable “in depicting heartiness,” says Dr. Doran, “ludicrous distress, grave or affected indifference, honest bravery, insurmountable cowardice, a spirited young or an enfeebled yet impatient old fellow, mischievous boyishness, good-humoured vulgarity, there was no one of his time who could equal him.”[589] Bannister left the stage with a handsome fortune. Hazlitt says finely of him that his “gaiety, good-humour, cordial feeling, and natural spirits shone through his characters and lighted them up like a transparency.”[590] His kind heart and honest[Pg 326] face were as well known as his good-humoured smile and buoyant activity. “Jack,” says Lamb, “was beloved for his sweet, good-natured moral pretensions.” He gave us “a downright concretion of a Wapping sailor, a jolly warm-hearted Jack Tar.”

Mrs. Jordan’s mother was the daughter of a Welsh clergyman who had eloped with an officer. The débutante came out at Drury Lane in 1785 as the heroine of “The Country Girl.” In 1789 she became the mistress of the Duke of Clarence. Good-natured, and endowed with a sweet clear voice, she played rakes with the airiest grace, and excelled in representing arch, buoyant girls, spirited, buxom, lovable women, and handsome hoydens. The critics complained of her as vulgar. Late in life she retired to France, and died in 1815. “Her wealth,” says Dr. Doran, “was lavished on the Duke of Clarence, who left her to die untended; but when he became king he ennobled all her children, the eldest being made Earl of Munster.” Hazlitt, speaking of Mrs. Jordan, says eloquently, her voice “was a cordial to the heart, because it came from it full, like the luscious juice of the rich grape. To hear her laugh was to drink nectar. Her smile was sunshine; her talking far above singing; her singing was like the twanging of Cupid’s bow. Her body was large, soft, and generous like the rose. Miss Kelly, if we may accept the judgment of Hazlitt, was in comparison a mere dexterous, knowing chambermaid. Jordan was all exuberance and grace. It was her capacity for enjoyment, and the contrast she presented to everything sharp, angular, and peevish, that delighted the spectator. She was Cleopatra turned into an oyster wench.”[591] Charles Lamb praises Mrs. Jordan for her tenderness in such parts as Ophelia, Helena, and Viola, and for her “steady, melting eye.”[592]