Haunted London, Index

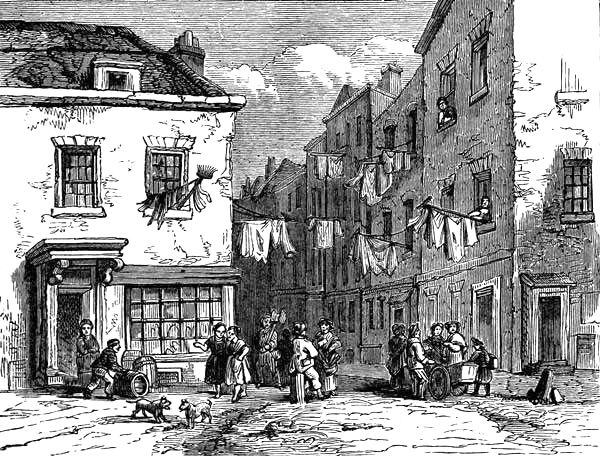

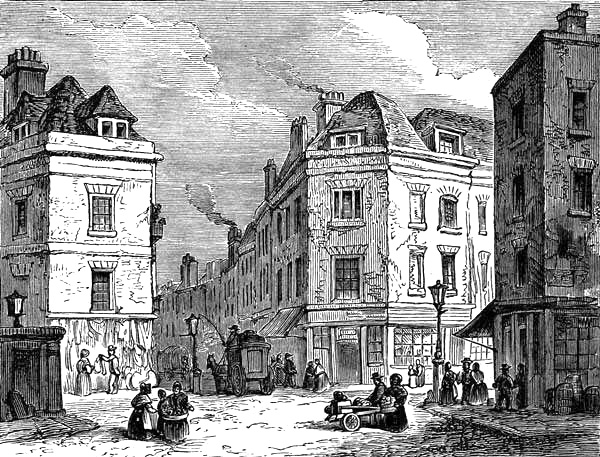

OLD ST. GILES’S—CHURCH LANE AND DYOT STREET, 1869.

CHAPTER XIII.

ST. GILES’S.

That ancient Roman military road (the Watling Street) came from Edgeware, and passing over Hyde Park and through St. James’s Park by Old Palace Yard, once the Wool Staple, it reached the Thames. Thence it was continued to Canterbury and the three great seaports.

Another Roman road, the Via Trinobantica, which began at Southampton and ended at Aldborough, ran through London, crossed the Watling Street at Tyburn, and passed along Oxford Street. In latter times, says Dr.[Pg 350] Stukeley, the road was changed to a more southerly direction, and Holborn was formed, leading to Newgate or the Chamberlain’s Gate.

One of the earliest tolls ever imposed in England is said to have had its origin in St. Giles’s.[611] In 1346 Edward III. granted to the Master of the Hospital of St. Giles and to John de Holborne, a commission empowering them to levy tolls for two years (one penny in the pound on their value) on all cattle and merchandise passing along the public highways leading from the old Temple, i.e. Holborn Bars, to the Hospital of St. Giles’s, and also along the Charing Road and another highway called Portpool, now Gray’s Inn Lane. The money was to be used in repairing the roads, which, by the frequent passing of carts, wains, horses, and cattle, had become so miry and deep as to be nearly impassable. The only persons exempted were to be lords, ladies, and persons belonging to religious establishments.[612]

Henry V. ascended the throne in 1413, and astonished his subjects by suddenly casting off his slough of vice, and becoming a self-restrained, virtuous, and high-spirited king. His first care was to forget party distinctions, and to put down the Lollards, or disciples of Wickliffe, whom the clergy denounced as dangerous to the civil power. As a good general secures the rear of his army before he advances, so the young king was probably desirous to guard himself against this growing danger before he invaded Normandy and made a clutch at the French crown.

Arundel, the primate, urged him to indict Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham, the head of the Lollard sect. The king was averse to a prosecution, and suggested milder means. At a conference, therefore, appointed before the bishops and doctors in 1414, the following articles were handed Oldcastle as tests, and the unorthodox lord was allowed two days to retract his heresies. He was required to confess that at the sacrament the material bread and[Pg 351] wine are turned into Christ’s very body and Christ’s very blood; that every Christian man ought to confess to an ordained priest; that Christ ordained St. Peter and his successors as his vicars on earth; that Christian men ought to obey the priest; and that it is profitable to go on pilgrimages and to worship the relics and images of saints. “This is determination of Holy Church. How feel ye this article?” With these stern words ended every dogma proposed by the primate.

Lord Cobham, who was much esteemed by the king, and had been a good soldier under his father, repeatedly refused to profess his belief in these tenets. The archbishop then delivered the heretic to the secular arm, to be put to death, according to the usage of the times. The night previous to his execution, however, Lord Cobham escaped from the Tower and fled to Wales, where he lay hid for four years while Agincourt was being fought, and where he must have longed to have been present with his true sword.

Soon after his escape, the frightened clergy spread a report that he was in St. Giles’s Fields, at the head of twenty thousand Lollards, who were resolved to seize the king and his two brothers, the Dukes of Bedford and Gloucester. For this imaginary plot thirty-six persons were hanged or burnt; but the names of only three are recorded, and of these Sir Roger Acton is the only person of distinction.

A reward of a thousand marks was offered for Lord Cobham, and other inducements were held out by Chicheley, the Primate Arundel’s successor. Four years, however, elapsed before the premature Protestant was discovered and taken by Lord Powis in Wales.[613] After some blows and blood a country-woman in the fray breaking Cobham’s leg with a stool, he was secured and sent up to London in a horse-litter. He was sentenced to be drawn on a hurdle to the gallows in St. Giles’s Fields, and to be hanged over a fire, in order to inflict on him the utmost pain.

He was brought from the Tower on the 25th of December 1418, and his arms bound behind him. He kept a[Pg 352] very cheerful countenance as he was drawn to the field where his assumed treason had been committed. When he reached the gallows, he fell devoutly on his knees and piously prayed God to forgive his enemies. The cruel preparations for his torment struck no terror in him, nor shook the constancy of the martyr. He bore everything bravely as a soldier, and with the resignation of a Christian. Then he was hung by the middle with chains and consumed alive in the fire, praising God’s name as long as his life lasted.

He was accused by his enemies of holding that there was no such thing as free will; that all sin was inevitable; and that God could not have prevented Adam’s sin, nor have pardoned it without the satisfaction of Christ.[614]

Fuller says of him: “Stage-poets have themselves been very bold with, and others very merry at, the memory of Sir John Oldcastle (Lord Cobham), whom they have fancied a boon companion or jovial roysterer, and yet a coward to boot, contrary to the credit of the chronicles, owning him to be a martial man of merit. Sir John Falstaff hath derided the memory of Sir John Oldcastle, and of late is substituted buffoon in his place; but it matters us little what petulant priests or what malicious poets have written against him.”

The gallows had been removed from the Elms at Smithfield in 1413, the first year of Henry V.; but Tyburn was a place of execution as early as 1388.[615] The St. Giles’s gallows was set up at the north corner of the hospital wall, between the termination of High Street and Crown Street, opposite to where the Pound stood.

The manor of St. Giles was anciently divided from Bloomsbury by a great fosse called Blemund’s Ditch. The Doomsday Book contains no mention of this district, nor indeed of London at all, except of ten acres of land nigh Bishopsgate, belonging to St. Paul’s, and a vineyard in Holborn, belonging to the Crown. This yard is supposed to have stood on the site of the Vine Tavern (now destroyed), a little to the east of Kingsgate Street.[616]

[Pg 353]Blemund’s Ditch was a line of defence running nearly parallel with the north side of Holborn, and connecting itself to the east with the Fleet brook. It was probably of British origin.[617] On the north-west of London, in the Roman times, there were marshes and forests, and even as late as Elizabeth, Marylebone and St. John’s Wood were almost all chase.

The manor was crown property in the Norman times, for Matilda, daughter of Malcolm king of Scotland and the queen of Henry I., built a leper hospital there, and dedicated it to St. Giles. The same good woman erected a hospital at Cripplegate, and another at St. Katharine’s, near the Tower, and founded a priory within Aldgate. The hospital of St. Giles sheltered forty lepers, one clerk, a messenger, the master, and several matrons; the queen gave 60s. a year to each leper. The inmates of lazar hospitals were in the habit of begging in the market-places.

The patron saint, St. Giles, was an Athenian of the seventh century, who lived as a hermit in a forest near Nismes. One day some hunters, pursuing a hind that he had tamed, struck the Greek with an arrow as he protected it, but the good man still went on praying, and refused all recompense for the injury. The French king in vain attempted to entice the saint from his cell, which in time, however, grew first into a monastery, and then into a town.[618]

This hospital was built on the site of the old parish church, and it occupied eight acres. It stood a little to the west of the present church, where Lloyd’s Court stands or stood; and its gardens reached between High Street and Hog Lane, now Crown Street, to the Pound, which used to stand nearly opposite to the west end of Meux’s Brewhouse. It was surrounded by a triangular wall, running in a line with Crown Street to somewhere near the Cock and Pye Fields (afterwards the Seven Dials), in a line with Monmouth Street, and thence east and west up High Street, joining near the Pound.

Unwholesome diet and the absence of linen seem to have[Pg 354] encouraged leprosy, which was probably a disease of Eastern origin. In 1179 the Lateran Council decreed that lepers should keep apart, and have churches and churchyards of their own. It was therefore natural to build hospitals for lepers outside large towns. King Henry II., for the health of the souls of his grandfather and grandmother, granted the poor lepers a second 60s. each to be paid yearly at the feast of St. Michael, and 30s. more out of his Surrey rents to buy them lights. He also confirmed to them the grant of a church at Feltham, near Hounslow. In Henry III.’s reign, Pope Alexander IV. issued a bull to confirm these privileges. Edward I. granted the hospital two charters in 1300 and 1303; and in Edward II.’s reign so many estates were granted to it that it became very rich. Edward III. made St. Giles a cell of Burton St. Lazar in Leicestershire. This annexation led to quarrels, and to armed resistance against the visitations of Robert Archbishop of Canterbury. In this reign the great plague broke out, and the king commanded the wards of the city to issue proclamations and remove all lepers. It is strange that St. Giles’s should have been the resort of pariahs from the very beginning.

Burton St. Lazar (a manor sold in 1828 for £30,000) is still celebrated for its cheeses. It remained a flourishing hospital from the reign of Stephen till Henry VIII. suppressed it. St. Giles’s sank in importance after this absorption, and finally fell in 1537 with its larger brother. By a deed of exchange the greedy king obtained forty-eight acres of land, some marshes, and two inns. Six years after the king gave St. Giles’s to John Dudley, Viscount Lisle, High Admiral of England, who fitted up the principal part of the hospital for his own residence. Two years after Lord Lisle sold the manor to Wymond Carew, Esq. The mansion was situated westward of the church and facing it. It was afterwards occupied by the celebrated Alice, Duchess of Dudley, who died there in the reign of Charles II., aged ninety. This house was subsequently the residence of Lord Wharton. It divided Lloyd’s Court from Denmark Street.

The master’s house, “The White House,” stood on the[Pg 355] site of Dudley Court, and was given by the duchess to the parish as a rectory-house. The wall which surrounded the hospital gardens and orchards was not entirely removed till 1639.

Early in the fourteenth century the parish of St. Giles, including the hospital inmates, numbered only one hundred inhabitants. In King John’s reign it was laid out in garden plots and cottages. In Henry III.’s reign it was a scattered country village, with a few shops and a stone cross, where the High Street now is. As far back as 1225 a blacksmith’s shop stood at the north-west end of Drury Lane, and remained there till its removal in 1575.

In Queen Elizabeth’s reign the Holborn houses did not run farther than Red Lion Street; the road was then open as far as the present Hart Street, where a garden wall commenced near Broad Street, St. Giles’s, and the end of Drury Lane, where a cluster of houses on the right formed the chief part of the village, the rest being scattered houses. The hospital precincts were at this time surrounded by trees. Beyond this, north and south, all was country; and avenues of trees marked out the Oxford and other roads. There was no house from Broad Street, St. Giles’s, to Drury House at the top of Wych Street.[619]

The lower part of Holborn was paved in the reign of Henry VI., in 1417; and in 1542 (33d Henry VIII.) it was completed as far as St. Giles’s, being very full of pits and sloughs, and perilous and noisome to all on foot or horseback. The first increase of buildings in this district was on the north side of Broad Street. Three edicts of 1582, 1593, and 1602 evince the alarm of Government at the increase of inhabitants and prohibit further building under severe penalties. The first proclamation, dated from Nonsuch Palace, in Surrey, assigns the reason of these prohibitions:—1. The difficulty of governing more people without new officers and fresh jurisdictions. 2. The difficulty of supplying them with food and fuel at reasonable rates. 3. The danger of plague and the injury to agriculture. Regulations were[Pg 356] also issued to prevent the further resort of country people to town, and the lord mayor took oaths to enforce these proclamations. But London burst through these foolish and petty restraints as Samson burst the green withs. In 1580 the resident foreigners in the capital had increased from 3762 to 6462 persons, the majority being Dutch who had fled from the Spaniards, and Huguenots who had escaped from France after the massacre of St. Bartholomew. St. Giles’s grew, especially to the east and west, round the hospital. The girdle wall was mostly demolished soon after 1595. Holborn, stretching westward, with its fair houses, lodgings for gentlemen, and inns for travellers,[620] had nearly reached it. In Aggas’s map, cattle graze amid intersecting footpaths, where Great Queen Street now is. There were then only two or three houses in Covent Garden, but in 1606 the east side of Drury Lane was built; in the assessment of 1623 upwards of twenty courtyards and alleys are mentioned; and 100 houses were added on the north side of St. Giles’s Street, 136 in Bloomsbury, 56 on the west side of Drury Lane, and 71 on the south side of Holborn.[621] The south and east sides of the hospital site had been the slowest in their growth. After the Great Fire, these still remained gardens, but the north side, nearer Oxford Road, was already occupied. The first inhabitants of importance were Mr. Abraham Speckart and Mr. Breads, in the reigns of James I. and Charles I., and afterwards Sir William Stiddolph. New Compton Street was originally called Stiddolph Street, but afterwards changed its name when Charles II. gave the adjoining marsh-land to Mr. Francis Compton, who built on the old hospital land a continuation of Old Compton Street. Monmouth Street, probably named after the foolish and unfortunate duke, was also built in this reign.

In 1694, in the reign of William III., a Mr. Neale, a lottery promoter, took on lease the Cock and Pye Fields—then the resort of gambling boys, thieves, and beggars, and a sink of filth and cesspools—and built the neighbouring[Pg 357] streets, placing in the centre a Doric pillar with seven dials on it; afterwards a clock was added.[622] This same Mr. Thomas Neale took a large piece of ground on the north side of Piccadilly from Sir Thomas Clarges, agreeing to lay out £10,000 in building; but he failed to carry out his design, and Sir Walter Clarges, after great trouble, got the lease out of his hands, and Clarges Street was then built.[623]

In 1697 many hundreds of the 14,000 French refugees who fled from Louis XIV.’s dragoons after the cruel revocation of the Edict of Nantes settled about Long Acre, the Seven Dials, and Soho. In Strype’s time (Queen Anne’s reign), Stacie Street, Kendrick Yard, Vinegar Yard, and Phoenix Street, were mostly occupied by poor French people; indigent marquises and starving countesses.

In the reign of Queen Anne, St. Giles’s increased with great rapidity—St. Giles’s Street and Broad Street from the Pound to Drury Lane, the south-east side of Tottenham Court Road, Crown Street, the Seven Dials, and Castle Street were completed; the south side of Holborn was also finished from Broad Street to a little east of Great Turnstile, and, on the north side, the street spread to two doors east of the Vine Tavern.[624] The Irish had already begun to debase St. Giles’s; the French refugees completed the degradation and hopelessness, and spread like a mud deluge towards Soho.

In 1640 there are in the parish books several entries of money paid to soldiers and distressed men who had lost everything they had in Ireland:—

| Paid to a poor Irishman, and to a prisoner come over from Dunkirk | £0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Paid for a shroud for an Irishman that died at Brickils | 0 | 2 | 6 |

In 1640, 1642, and 1647, there constantly occur donations to poor Irish ministers and plundered Irish. Clothes were sent by the parish into Ireland. There is one entry—

| Paid to a poor gentleman undone by the burning of a city in Ireland; having licence from the lords to collect |

£0 | 3 | 0 |

The following entries are also curious and characteristic:—

| 1642.— | To Mrs. Mabb, a poet’s wife, her husband being dead | £0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Paid to Goody Parish, to buy her boys two shirts; and Charles, their father, a waterman at Chiswick, to keep him at £20 a year from Christmas |

0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 1648.— | Gave to the Lady Pigot, in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, poor and deserving relief |

0 | 2 | 6 | |

| 1670.— | Given to the Lady Thornbury, being poor and indigent | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| 1641.— | To old Goodman Street and old Goody Malthus, very poor |

——— | |||

| 1645.— | To Mother Cole and Mother Johnson, xiid. a-piece | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| 1646.— | To William Burnett, in a cellar in Raggedstaff Yard, being poor and very sick |

0 | 1 | 6 | |

| To Goody Sherlock, in Maidenhead-fields Lane, one linen-wheel, and gave her money to buy flax |

0 | 1 | 0 | ||

There are also some interesting entries showing what a sink for the poverty of all the world the St. Giles’s cellars had become, even before the Restoration.

| 1640.— | Gave to Signor Lifecatha, a distressed Grecian | ——— | |||

| 1642.— | To Laylish Milchitaire, of Chimaica, in Armenia, to pass him to his own country, and to redeem his sons in slavery under the Turks |

£0 | 5 | 0 | |

| 1654.— | Paid towards the relief of the mariners, maimed soldiers, widows and orphans of such as have died in the service of Parliament |

4 | 11 | 0 | |

These were for Cromwell’s soldiers; and this year Oliver himself gave £40 to the parish to buy coals for the poor.

| 1666.— | Collected at several times towards the relief of the poor sufferers burnt out by the late dreadful fire of London |

£25 | 8 | 4 |

In 1670 nearly £185 was collected in this parish towards the redemption of slaves.

After 1648 the Irish are seldom mentioned by name. They had grown by this time part and parcel of the district, and dragged all round them down to poverty. In 1653 an assistant beadle was appointed specially to search out and report all new arrivals of chargeable persons. In 1659 a monthly vestry-meeting was instituted to receive the constable’s report as to new vagrants.

In 1675 French refugees began to increase, and in 1679-1680, 1690 and 1692 fresh efforts were made to search out and investigate the cases of all new-comers. In 1710 the churchwardens reported to the commissioners for building new churches, that “a great number of French Protestants were inhabitants of the parish.”

Well-known beggars of the day are frequently mentioned in the parish accounts, as for instance—

| 1640.— | Gave to Tottenham Court Meg, being very sick | £0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1642.— | Gave to the ballad-singing cobbler | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1646.— | Gave to old Friz-wig | 1 | 6 | 0 | |

| 1657.— | Paid the collectors for a shroud for old Guy, the poet | 0 | 2 | 6 | |

| 1658.— | Paid a year’s rent for Mad Bess | 1 | 4 | 6 | |

| 1642.— | Paid to one Thomas, a traveller | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| To a poor woman and her children, almost starved | 0 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1645.— | For a shroud for Hunter’s child, the blind beggar-man | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| 1646.— | Paid and given to a poor wretch, name forgot | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Given to old Osborn, a troublesome fellow | 0 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Paid to Rotton, the lame glazier, to carry him towards Bath | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 1647.— | To old Osborne and his blind wife | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| To the old mud-wall maker | 0 | 0 | 6 |

[Pg 360]In 1665 the plague fell heavily on St. Giles’s, already dirty and overcrowded. The pest had already broken out five times within the eighty years beginning in 1592; but no outbreak of this Oriental pest in London had carried off more than 36,000 persons. The disease in 1665, however, slew no fewer than 97,306 in ten months.[625] In St. Giles’s the plague of 1592 carried off 894 persons; in 1625 there died of the plague about 1333; but in 1665 there were swept off from this parish alone 3216. The plague of 1625 seemed to have alarmed London quite as much as its successor, for we find that in St. Giles’s no assessment could be made, as the richer people had all fled into the country. A pest-house was fitted up in Bloomsbury for the nine adjoining parishes, and this was afterwards taken by St. Giles’s for itself. The vestry appointed two examiners to inspect infected houses. Mr. Pratt, the churchwarden, who advanced money to succour the poor when the rich deserted them, was afterwards paid forty pounds for the sums he had generously disbursed at his own risk. In 1642 the entries in the parish books show that the disease had again become virulent and threatening. The bodies were collected in carts by torchlight, and thrown without burial service into large pits. Infected houses were padlocked up, and watchmen placed to admit doctors or persons bringing food to the searchers, who at night brought out the dead.

The following entries (for 1642) in the parish books seem to me even more terrible than Defoe’s romance written fifty years after the events:—

| Paid for the two padlocks and hasps for visited houses | £0 | 2 | 6 | |

| Paid Mr. Hyde for candles for the bearers | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| "to the same for the night-cart and cover | 7 | 9 | 0 | |

| "to Mr. Mann for links and candles for the night-bearers | 0 | 10 | 0 |

The next year the plague still raged, and the same precautions seem to have been taken as afterwards in 1665,[Pg 361] showing that the terrible details of that punishment of filth and neglect were not new to London citizens.

The entries go on:—

| To the bearers for carrying out of Crown Court a woman that died of the plague |

£0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Sent to a poor man shut up in Crown Yard of the plague | 0 | 1 | 6 |

Then follow sums paid for padlocks and staples, graves and links:—

| Paid and given Mr. Lyn, the beadle, for a piece of good service to the parish in conveying away of a visited household to Lord’s Pest House, forth of Mr. Higgins’s house at Bloomsbury |

£0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Received of Mr. Hearle (Dr. Temple’s gift) to be given to Mrs. Hockey, a minister’s widow, shut up in the Crache Yard of the plague |

0 | 10 | 0 |

But now came the awful pestilence of 1665; the streets were so deserted that grass grew in them, and nothing was to be seen but coffins, pest-carts, link-men, and red-crossed doors. The air resounded with the tolling of bells, the screams of distracted mourners crying from the windows, “Pray for us!” and the dismal call of the searchers, “Bring out your dead!”[626]

The plague broke out in its most malignant form among the poor of St. Giles’s;[627] and Dr. Hodges and Sir Richard Manningham, both first-rate authorities on this subject, agree in this assertion.

In August 1665 an additional rate to the amount of £600 was levied. Independent of this, very large sums were subscribed by persons resident in, or interested in, the parish. The following are a few of the items:—

| Mr. Williams, from the Earl of Clare | £10 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mr. Justice (Sir Edmondbury) Godfrey, from the Lord Treasurer |

50 | 0 | 0 | |

| [Pg 362]Earl Craven and the rest of the justices, towards the visited poor, at various times |

449 | 16 | 10 | |

| Earl Craven towards the visited poor | 40 | 3 | 0 |

There are also these ominous entries:—

| August.— | Paid the searchers for viewing the corpse of Goodwife Phillips, who died of the plague |

£0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Laid out for Goodman Phillips and his children, being shut up and visited |

0 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Laid out for Lylla Lewis, 3 Crane Court, being shut up of the plague; and laid out for the nurse, and for the nurse and burial |

0 | 18 | 6 |

In July 1666 the constables, etc. were ordered to make an account of all new inmates coming to the parish, and to take security that they would not become burdensome. They were also directed to be careful to prevent the infection spreading for the future by a timely guard of all “that are or hereafter may happen to be visited.”

“During the plague time,” says an eye-witness, “nobody put on black or formal mourning, yet London was all in tears. The shrieks of women and children at the doors and windows of their houses where their dearest relations were dying, or perhaps dead, were enough to pierce the stoutest hearts. At the west end of the town it was a surprising thing to see those streets which were usually thronged now grown desolate; so that I have sometimes gone the length of a whole street (I mean bye streets), and have seen nobody to direct me but watchmen[628] sitting at the doors of such houses as were shut up; and one day I particularly observed that even in Holborn the people walked in the middle of the street, and not at the sides—not to mingle, as I supposed, with anybody that came out of infected houses, or meet with smells and scents from them.”

Dr. Hodges, a great physician, who shunned no danger, describes even more vividly the horrors of that period. “In the streets,” he says, “might be seen persons seized with[Pg 363] the sickness, staggering like drunken men; here lay some dozing and almost dead; there others were met fatigued with excessive vomiting, as if they had drunk poison; in the midst of the market, persons in full health fell suddenly down as if the contagion was there exposed to sale. It was not uncommon to see an inheritance pass to three heirs within the space of four days. The bearers were not sufficient to inter the dead.”[629]

It is supposed that till the Leper Hospital was suppressed, the St. Giles’s people used the oratory there as their parish church. Leland does not mention any other church, although he lived and wrote about the time of the suppression, and even made an effort to save the monastic MSS. by proposing to have them placed in the king’s library. The oratory had probably a screen walling off the lepers from the rest of the congregation. It boasted several chantry chapels, and a high altar at the east end, dedicated to St. Giles, before which burnt a great taper called “St. Giles’s light,” and towards which, about A.D. 1200, one William Christemas bequeathed an annual sum of twelvepence. There was also a Chapel of St. Michael, appropriated to the infirm, and which had its own special priest.

In the reign of Charles I. the south aisle of the hospital church was full of rubbish, lumber, and coffin-boards; and Lady Dudley put up a screen to divide the nave from the chancel. In 1623 the church became so ruinous that it had to be rebuilt at an expense of £2068: 7: 2. Among the subscribers appear the names of the Duchess of Lennox, Sir Anthony Ashleye, Sir John Cotton, and the players at “the Cockpit playhouse.” The 415 householders of the parish subscribed £1065: 9s., the donations ranging from the £250 of the Duchess of Dudley to Mother Parker’s twopence.

Nearly five years elapsed before the new church was consecrated. On the 9th of June 1628 Pym brought a charge against the rector, Dr. Mainwaring, for having preached two obnoxious sermons, entitled “Religion”[Pg 364] and “Allegiance,” and accused the imprudent time-server of persuading citizens to obey illegal commands on pain of damnation, and framing, like Guy Faux, a mischievous plot to alter and subvert the Government.[630] The third sermon in which Mainwaring defended his two first, the stern Commons found upon inquiry[631] had been printed by special command of the king. It was as full of mischief as a bomb-shell. It held that on any exigency all property was transferred to the sovereign; that the consent of Parliament was not necessary for the imposition of taxes; and that the divine laws required compliance with every demand which a prince should make upon his subjects. For these doctrines the Commons impeached Mainwaring; the sentence pronounced on him was, that he should be imprisoned during the pleasure of the House, that he should be fined £1000, to the king, make submission of his offence, be suspended from lay and ecclesiastical office for three years, and that his sermons be called in and burnt.

On June 20 the courtly preacher came to the House, and on his knees submitted himself in sorrow and repentance for the errors and indiscretions he had been guilty of in preaching the sermons “rashly, scandalously, and unadvisedly.” He further acknowledged the three sermons to be full of dangerous passages and aspersions, and craved pardon for them of God and the king. No sooner was the session over than the wilful king pardoned him, promoted him to the deanery of Winchester, and some years after to the bishopric of St. David’s.[632]

The new church was consecrated on the 26th of January 1630. Bishop Laud performed the ceremony, and was entertained at the house of a Mr. Speckart, near the church. There were two tables sufficient to seat thirty-two persons. The broken churchyard wall was fenced up with boards, the altar hung with green velvet, a rail made to keep the mob from the west door, and a train of constables, armed with bills and halberts, appointed to maintain order if the Puritans became threatening. The new rector, Dr. Heywood, had[Pg 365] been chaplain to Laud, and was probably of the High Church party. Like his expelled predecessor, he had been chaplain to one of the most arbitrary of kings. In 1640 the Puritans, gaining strength, petitioned Parliament against him, stating that he had set up crucifixes and images of saints, likewise organs, “with other confused music, etc., hindering devotion and maintained at the great and needless charge of the parish.” They described the carved screen as particularly obnoxious, and they objected to the altar rail, the chancel carpet, the purple velvet in the desk, the needlework covers of the books, the tapestry, the lawn cloth, the bone lace of the altar cloths, and the taffeta curtains on the walls. These “popish and superstitious” ornaments were sold by order of Parliament, all but the plate and the great bell. The surplices were given away. The twelve apostles were washed off the organ-loft, and the painted glass was taken down from the windows. The screen was sold for forty shillings, and the money given to the poor. The Covenant was framed and hung up in the church, and five shillings given to a pewterer for a new basin cut square on one side for baptisms. The blue velvet carpet, embroidered cushions, and blue curtains were sold, and so were the communion rails. In 1647 Lady Dudley’s pew was lined with green baize and supplied with two straw mats. In 1650 the king’s arms were taken out of the windows, and a sun-dial was substituted. The organ-loft was let as a pew.

The Restoration soon followed on these paltry excesses of a low-bred fanaticism. The ringers of St. Giles’s rang a peal for three days running. The king’s arms in the vestry and the windows were restored. Galleries were erected for the nobility. In 1670 a brass chandelier of sixteen branches was bought for the church, and an hour-glass for the pulpit.

In 1718 the old hospital church had become damp and unwholesome. The grave-ground had risen eight feet, so that the church lay in a pit. Parliament was therefore petitioned that St. Giles’s should be one of the fifty new churches. It was urged that a good church facing the High Street, the chief thoroughfare for all persons who travelled the Oxford[Pg 366] or Hampstead roads, would be a great ornament. The petitioners also contended that St. Giles’s already spent £5300 a year on the poor, and that a new rate would impoverish many industrious persons. The Duke of Newcastle, the Lord Chancellor, and other eminent parishioners strenuously supported the petition, which, on the other hand, was warmly opposed by the Archbishop of York, five bishops, and eleven temporal peers. The opposition contended that the parish was well able to repair the present church; that the fund given for building new churches was never meant to be devoted to rebuilding old ones; and that so far from the parish not requiring church accommodation, St. Giles’s contained 40,000 persons, a number for which three new churches would be barely sufficient.[633] Eleven years longer the church remained a ruin, when in 1729 the commissioners granted £8000 for a new church, provided that the parish would settle £350 a year on the rector of the new parish of Bloomsbury.

The architect of the new church, opened in 1734, was Henry Flitcroft. The roof is supported by Ionic pillars of Portland stone. The steeple is 160 feet high, and consists of a rustic pedestal supporting Doric pilasters; over the clock is an octangular tower, with three-quarter Ionic columns supporting a balustrade with vases. The spire is octangular and belled. This hideous production of Greek rules was much praised by the critics of 1736. They called it “simple and elegant.” They considered the east end as “pleasing and majestic,” and found nothing in the west to object to but the smallness and poverty of the doors. The steeple they described as “light, airy, and genteel.”[634] whether taken with the body of the church or considered as a separate building.

In 1827 the clock of St. Giles’s Church was illuminated with gas, and the novelty and utility of the plan “attracted crowds to visit it from the remotest parts of the metropolis.”[635]

[Pg 367]St. Giles’s Churchyard was enlarged in 1628, and again soon after the Restoration. The garden plot from which the new part was divided was called Brown’s Gardens. In 1670 we find the sexton agreeing, on condition of certain windows he had been allowed to introduce into the side of his house, facing the churchyard, to furnish the rector and churchwardens, every Tuesday se’nnight after Easter, with two fat capons ready dressed.

In 1687 the Resurrection Gate, or Lich Gate, as it was called, and which still exists, was erected at a cost of £185: 14: 6. It stood for many years farther to the west than the old gate, and contains a heap of dully-carved figures in relievo, abridged from Michael Angelo’s “Last Judgment,” and crowded under a large “compass pediment.” It has lately, however, been replaced in its old position. This work was much admired and celebrated, but “Nollekens” Smith says that it is poor stuff.

Pennant, always shrewd and vivacious, was one of the first writers who exposed the disgraceful and dangerous condition of the London churchyards. He describes seeing at St Giles’s a great square pit with rows of coffins piled one upon the other, exposed to sight and smell, awaiting the mortality of the night. “I turned away,” he says, “disgusted at the scene, and scandalised at the want of police which so little regards the health of the living as to permit so many putrid corpses, packed between some slight boards, dispersing their dangerous effluvia over the capital.”[636]

In 1808 a new burial-ground for St. Giles’s parish was consecrated in St. Pancras’s. It stands in grim loneliness between the Hampstead Road and College Street, Camden Town.

The graves of John Flaxman, the sculptor, and his wife and sister, are marked by an altar tomb of brick, surmounted by a thick slab of Portland stone. Near it is the ruinous tomb of ingenious, faddling Sir John Soane, the architect to the Bank of England. It is a work of great pretension, “but cut up into toy-shop prettiness, with all[Pg 368] the peculiar defects of his style and manner.” Two black cypresses mark the grave.[637]

A few eminent persons are buried in the old St. Giles’s Churchyard. Amongst these, the most illustrious is George Chapman, who produced a fine though rugged translation of the Iliad which is to Pope’s what heart of oak is to veneer, and who died in 1634 aged seventy-seven, and lies buried here. Inigo Jones generously erected an altar tomb to his memory at his own expense; it is still to be seen in the external southern wall of the church. The monument is old; but the inscription is only a copy of all that remained visible of the old writing. That chivalrous visionary, Lord Herbert of Cherbury, was also buried here, and so was James Shirley, the dramatist, who died in 1666. The latter was the last of the great ante-Restoration play-writers, and of a thinner fibre than any of the rest, except melancholy Ford.

Richard Pendrell, the Staffordshire farmer, “the preserver and conductor of King Charles II. after his escape from Worcester Fight,” has an altar tomb to his memory raised in this churchyard. After the Restoration, Richard came to town, to be in the way, I suppose, of the good things then falling into Cavaliers’ mouths, and probably settled in St. Giles’s to be near the Court. The story of the Boscobel oak was one with which the swarthy king delighted to buttonhole his courtiers. Pendrell died in 1671, and had a monument erected to his memory on the south-east side of the church. The black marble slab of the old tomb forms the base of the present one. The epitaph is in a strain of fulsome bombast, considering the king who was preserved showed his gratitude to Heaven only by a long career of unblushing vice, and by impoverishing and disgracing the foolish country that called him home. It begins thus:—

“Hold, passenger! here’s shrouded in this hearse

Unparalleled Pendrell thro’ the universe.

Like when the eastern star from heaven gave light

To three lost kings, so he in such dark night

[Pg 369]To Britain’s monarch, lost by adverse war,

On earth appeared a second eastern star.”

The dismal poet ends by assuring the world that Pendrell, the king’s pilot, had gone to heaven to be rewarded for his good steering. In 1702 a Pendrell was overseer in this parish. About 1827 a granddaughter of this Richard lived near Covent Garden, and still enjoyed part of the family pension. In 1827 Mr. John Pendrell, another descendant of Richard, died at Eastbourne.[638] His son kept an inn at Lewes, and was afterwards clerk at a Brighton hotel.

The only monument at present of interest in the church is a recumbent figure of the Duchess Dudley, the great benefactor of the parish, created a duchess in her own right by Charles I. She died 1669. The monument was preserved by parochial gratitude when the church was rebuilt, in consideration of the duchess’s numerous bequests to the parish. She was buried at Stoneleigh in Warwickshire. This pious and charitable lady was the daughter of Sir Thomas Leigh of Stoneleigh, and she married Sir Robert Dudley, son of the great Earl of Leicester, who deserted her and his five daughters, and went and settled in Florence, where he became chamberlain to the Grand Duchess. Clever and unprincipled as his father, Sir Robert devised plans for draining the country round Pisa, and improving the port of Leghorn. He was outlawed, and his estates at Kenilworth, etc. were confiscated and sold for a small sum to Prince Henry; but Charles I. generously gave them back to the duchess.

In her funeral sermon, Dr. Boreman says of this good woman: “She was a magazine of experience.... I have often said she was a living chronicle bound up with the thread of a long-spun age. And in divers incidents and things relating to our parish, I have often appealed to her stupendous memory as to an ancient record.... In short, I would say to any desirous to attain some degree of perfection, ‘Vade ad Sancti Egidii oppidum, et disce Ducinam Dudleyam’—(‘Come to St. Giles, and inquire the character of Lady Dudley’).”[639]

[Pg 370]The oldest monument remaining in the churchyard in 1708 was dated 1611. It was a tombstone, “close to the wall on the south side, and near the west end,” and was to the memory of a Mrs. Thornton.[640] Her husband was the builder of Thornton Alley, which was probably his estate. The following painful lines were round the margin of the stone:—

“Full south this stone four foot doth lie

His father John and grandsire Henry

Thornton, of Thornton, in Yorkshire bred,

Where lives the fame of Thornton’s being dead.”

Against the east end of the north aisle of the church was the tombstone of Eleanor Steward, who died 1725, aged 123 years and five months.

That good and inflexible patriot, Andrew Marvell, the most poignant satirist of King Charles II., died in 1678, and is buried in St. Giles’s. Marvell was Latin secretary to Milton, and in the school of that good man’s house learnt how a true patriot should live. It is recorded that one day when he was dining in Maiden Lane, one of Charles II.’s courtiers came to offer him £1000 as a bribe for his silence. Marvell refused the gift, took off the dish-cover, and showed his visitor the humble half-picked mutton-bone on which he was about to dine. He was member for Kingston-upon-Hull for nearly twenty years, and was buried at last at the expense of his constituents. They also voted a sum of money to erect a monument to him with a harmless epitaph; to this, however, the rector of the time, to his own disgrace, refused admittance. Thompson, the editor of Marvell’s works, searched in vain in 1774 for the patriot’s coffin. He could find no plate earlier than 1722.

In the same church with this fixed star rests that comet, Sir Roger l’Estrange. His monument was said to be the grandest in the church. Sir Roger died in 1704, aged eighty-eight.

In 1721, after an ineffectual treaty for Dudley Court, where the parsonage-house had once stood, a piece of[Pg 371] ground called Vinegar Yard was purchased for the sum of £2252: 10s. as a burial-ground, hospital, and workhouse for the parish of St. Giles’s. At that time St. Giles’s relieved about 840 persons, at the cost of £4000 a year. Of this number there were 162 over seventy years of age, 126 parents overburthened with children, 183 deserted children and orphans, 70 sick at parish nurses’, and 300 men lame, blind, and mad.

The Earl of Southampton granted land for five almshouses in St. Giles’s in 1656.[641] The site was in Broad Street, nearly at the north end of Monmouth and King Streets, where they stood until 1782, at which period they were pulled down to widen the road. The new almshouses were erected in a close, low, and unhealthy spot in Lewknor’s Lane.

In the year 1661 Mr. William Shelton left lands for a school for fifty children in Parker’s Lane, between Drury Lane and Little Queen Street. The tenements, before he bought them, had been in the occupation of the Dutch ambassador. The premises were poor houses, and a coach-house and stables in the occupation of Lord Halifax. In 1687, the funds proving inadequate, the school was discontinued; but in 1815, after being in abeyance for fifty-three years, it was re-opened in Lloyd’s Court.[642]

The select vestry of St. Giles’s was much badgered in 1828 by the excluded parishioners. There were endless errors in the accounts, and items amounting to £90,000 were found entered only in pencil. The special pleas put in by the attorneys of the vestry covered 175 folios of writing.

Hog Lane, built in 1680, was rechristened in 1762 Crown Street, as an inscription on a stone let into the wall of a house at the corner of Rose Street intimates.[643] Strype calls it a “place not over well built or inhabited.” The Greeks had a church here, afterwards a French refugee place of worship, and subsequently an Independent chapel. It[Pg 372] stood on the west side of the lane, a few doors from Compton Street; and its site is now occupied by St. Mary’s Church and clergy-house. Hogarth laid the scene of his “Noon” in Hog Lane, at the door of this chapel; but the houses being reversed in the engraving, the truth of the picture is destroyed. The background contains a view of St. Giles’s Church. The painter delighted in ridiculing the fantastic airs of the poor French gentry, and showed no kindly sympathy with their honest poverty and their sufferings. It was to St. Giles’s that Hogarth came to study poverty and also vice. A scene of his “Harlot’s Progress” is in Drury Lane, close by. Tom Nero, in the “Four Stages of Cruelty,” is a St. Giles’s charity-boy, and we see him in the first stage tormenting a dog near the church. Hogarth’s “Gin Street” is situated in St. Giles’s. The scenes of all the most hideous and painful of his works are in this district.

“Nollekens” Smith, writing of St. Giles’s, says: “I recollect the building of most of the houses at the north end of New Compton Street—so named in compliment to Bishop Compton, Dean of St. Paul’s. I also remember a row of six small almshouses, surrounded by a dwarf brick wall, standing in the middle of High Street. On the left hand of High Street, passing into Tottenham Court Road, there were four handsome brick houses, probably of Queen Anne’s time, with grotesque masks as keystones to the first-floor windows. Nearly on the site of the new “Resurrection Gate,” in which the basso-relievo is, stood a very small old house towards Denmark Street, which used to totter, to the terror of passers by, whenever a heavy carriage rolled through the street.”[644]

Exactly where Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road meet in a right angle, a large circular boundary-stone was let into the pavement. Here when the charity-boys of St. Giles’s walked the boundaries, those who deserved flogging were whipped, in order to impress the parish frontier on their memories.

[Pg 373]The Pound originally stood in the middle of the High Street, whence it was removed in 1656 to make way for the almshouses. It had stood there when the village really required a place to imprison straying cattle. The latest pound stood in the broad space where the High Street, Tottenham Court Road, and Oxford Street meet; it occupied a space of about thirty-feet, and was removed in 1768. It must have faced Meux’s Brewery. An old song that celebrates this locality begins—

“At Newgate steps Jack Chance was found,

And bred up near St. Giles’s Pound.”

Criminals on their way to Tyburn used to “halt at the great gate of St. Giles’s Hospital, where a bowl of ale was provided as their last refreshment in this life.”[645] A similar custom prevailed at York, which gave rise to the proverb, “The saddler of Bawtry was hung for leaving his liquor,” meaning that if the impatient man had stopped to drink, his reprieve would have arrived in time.[646]

Bowl Yard was built about 1623, and was then surrounded by gardens. It is a narrow court on the south side of High Street, over against Dyot Street, now George Street. There was probably here a public-house, the Bowl, at which in later time ale was handed to the passing thieves.

Swift, in a spirited ballad describes “clever Tom Clinch,” who rode “stately through Holborn to die in his calling,” stopping at the George for a bottle of sack, and promising to pay for it “when he came back.” No one has sketched the highwayman more perfectly than the Irish prelate. Tom Clinch wears waistcoat, stockings, and breeches of white, and his cap is tied with cherry ribbon. He bows like a beau at the theatre to the ladies in the doors and to the maids in the balconies, who cry, “Lackaday, he’s a proper young man.” He swears at the hawkers crying his last speech, kicks the hangman when he kneels to ask his pardon, makes a short speech exhorting his comrades to ply their[Pg 374] calling, and so carelessly and defiantly takes his leave of an ungrateful world.

“Rainy Day” Smith describes,[647] when a boy of eight years old, being taken by Nollekens, the sculptor, to see that notorious highwayman John Rann, alias “Sixteen-string Jack,” on his way to execution at Tyburn, for robbing Dr. Bell, chaplain to the Princess Amelia, in Gunnersbury Lane, near Brentford, in 1774. Rann was a smart fellow, and had been a coachman to Lord Sandwich, who then lived at the south-east corner of Bedford Row, Covent Garden. The undaunted malefactor wore a bright pea-green coat, and carried an immense nosegay, which some mistress of the highwayman had handed him, according to custom, as a last token, from the steps of St. Sepulchre’s Church. The sixteen strings worn by this freebooter at his knees were reported to be in ironical allusion to the number of times he had been acquitted. On their return home, Nollekens, stooping to the boy’s ear, assured him that had his father-in-law, Mr. Justice Welch, been then High Constable, they could have walked all the way to Tyburn beside the cart.[648]

Holborn used to be called “the Heavy Hill” because it led thieves from Newgate to Tyburn. Old fat Ursula, the roast-pig seller in Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair talks of ambling afoot to hear Knockhem the footpad groan out of a cart up the Heavy Hill. This was in James I.’s time. Dryden alludes to it in the same way in 1678,[649] and in 1695 Congreve’s Sir Sampson[650] mentions the same doleful procession. In 1709 (Queen Anne) Tom Browne mentions a wily old counsellor in Holborn who used to turn out his clerks every execution day for a profitable holiday, saying, “Go, you young rogues, go to school and improve.”

St. Giles’s was always famous for its inns.[651] One of the oldest of these was the Croche House, or Croche Hose (Cross[Pg 375] Hose), so called from its sign—the Crossed Stockings. The sign, still used by hosiers, was a red and white stocking forming a St. Andrew’s Cross. This inn belonged to the hospital cook in 1300, and was given by him to the hospital. It stood at the north of the present entrance to Compton Street, and was probably destroyed before the reign of Henry VIII.

The Swan on the Hop was an inn of Edward III.’s time; it stood eastward of Drury Lane and on the south side of Holborn.[652]

The White Hart is described in Henry VIII.’s time as possessing eighteen acres of pasture. It stood near the Holborn end of Drury Lane, and existed till 1720. In Aggas’s Plan it appears surrounded on three sides by a wall. It was bounded on the east by Little Queen Street, and was divided from Holborn by an embankment. A court afterwards stood on its site.

The Rose is mentioned as early as Edward III.’s reign. It was near Lewknor’s Lane, and stood not far from the White Hart.

The Vine was an inn till 1816. It was on the north side of Holborn, a little to the east of Kingsgate Street. It is supposed to have stood on the site of a vineyard mentioned in Doomsday Book. It was originally a country roadside inn, with fields at the back. It became an infamous nuisance. The house that replaced it was first occupied by a timber-merchant, and afterwards by Probert, the accomplice of Thurtell, who, escaping death for the murder of Mr. Weare, was soon after hanged for horse-stealing in Gloucestershire. It was at this trial that the prisoner’s keeping a gig was adduced as an incontestible proof of his respectability—a fact immortalised, almost to the weariness of a degenerate age, by Mr. Thomas Carlyle. The inn was once called the Kingsgate Tavern, from its having stood near the king’s gate or turnpike in the adjoining street.

The Cock and Pye Inn stood at the west corner of what was once a mere or marshland. The fields surrounding it,[Pg 376] now Seven Dials, were called from it the Cock and Pye Fields.

The Maidenhead Inn stood in Dyot Street, and formed part of Lord Mountjoy’s estates in Elizabeth’s time. It was the house for parish meetings in Charles II.’s reign. It then became a resort for mealmen and farmers, and latterly a brandy-shop and beggars’ haunt of the vilest sort. It was finally turned into a stoneyard. Dyot Street, so called after Sir John Dyot, who left it by wish to the poor, though it was afterwards a poor and even dangerous locality, must have been respectable in 1662, when a Presbyterian chapel was built there for Joseph Read, Baxter’s friend, an ejected minister from Worcestershire. Read was taken up under the Conventicles Act in 1677, and endured much persecution, but was restored to his congregation on the accession of James II. From 1684 to 1708 the building was used as a chapel of ease to St. Giles’s Church. At the close of the last century men would hurry along Dyot Street as through a dangerous defile. There was a legend current of a banker’s clerk who, returning from his round, with his book of notes and bills fastened by the usual chain, as he passed down Dyot Street felt a cellar door sinking under him. Conscious of his danger, he made a spring forward, dashed down the street, and escaped the trap set for him by the thieves. It may be added that Dyot Street gave the name to a song sung by Liston in the admirable burlesque of “Bombastes Furioso.”

Irish mendicants—the poorest, dirtiest, and most unimprovable of all beggars—began to crowd into St. Giles’s about the time of Queen Elizabeth.[653]

The increase of London soon attracted country artisans and country beggars. The closing of the monasteries had filled England with herds of sturdy and dangerous vagrants not willing to work, and by no means inclined to starve. The new-comers resorting to the suburbs of London to escape the penalties of infringing the City jurisdiction, the stout-hearted queen ordered all persons within three miles[Pg 377] of London gates to forbear from allowing any house to be occupied by more than one family.

A proclamation of 1583 alludes to the very poor and the beggars, who lived “heaped up” in small tenements and let lodgings. A subsequent warning orders the suppression of the great multitude of Irish vagrants, many of whom haunted the courts under pretence of suits; by day they mixed with disbanded soldiers from the Low Countries and other impostors and beggars, and at night committed robberies and outrages. St. Giles’s was then one of the great harbours for these “misdemeaned persons.” On one occasion a mob of these rogues surrounded the queen as she was riding out in the evening to Islington to take the air. That same night Fleetwood, the Recorder, issued warrants, and in the morning went out himself and took seventy-four rogues, including some blind rich usurers, who were all sent to Bridewell for speedy punishment.

James I. pursued the same crusade against vagrants, forbidding new buildings in the suburbs, and ordering all newly raised structures to be pulled down. The beadles had to attend every Sunday at the vestry to report all new inmates, and who lodged them, and to take up all idlers; the constables in 1630 were also required to give notice of such persons to the churchwardens every month. In an entry in St. Giles’s parish books in 1637 “families in cellars” are first mentioned.[654] The locality afterwards became noted for these dens, and “a cellar in St. Giles’s” became a proverbial phrase to signify the lowest poverty.

In 1640 Irishmen are first mentioned by name, and money was paid to take them back again to their native land.

Sir John Fielding, brother of the great novelist, who was an active Westminster magistrate in his time and a great hunter down of highwaymen, in a pamphlet on the increase of crime in London, lays special stress on the vicious poverty of St. Giles’s. He gives a statement on the authority of Mr. Welch, the High Constable of Holborn, of the overcrowding of the miserable lodgings where idle persons and[Pg 378] vagabonds were sheltered for twopence a night. One woman alone owned seven of these houses, which were crowded with twopenny beds from cellar to garret. In these beds both sexes, strangers or not, lay promiscuously, the double bed being a halfpenny cheaper. To still more wed vice to poverty, these lodging-house keepers sold gin at a penny a quartern, so that no beggar was so poor that he could not get drunk. No fewer than seventy of these vile houses were found open at all hours, and in one alone, and not the largest, there were counted fifty-eight persons sleeping in an atmosphere loathsome if not actually poisonous.

This Judge Welch was the father of Mrs. Nollekens, and a brave and benevolent man. He was a friend of Dr. Johnson and of Fielding, whom he succeeded in his justiceship, Mr. Welch having on one occasion heard that a notorious highwayman who infested the Marylebone lanes was sleeping in the first floor of a house in Rose Street, Long Acre, he hired the tallest hackney-coach he could find, drove under the thief’s window, ascended the roof, threw up the sash, entered the room, actually dragged the fellow naked out of bed on to the roof of the coach, and in that way carried him down New Street and up St. Martin’s Lane, amidst the huzzas of an immense throng which followed him, to Litchfield Street, Soho.[655]

Archenholz, the German traveller, writing circa 1784, describes the streets of London as crowded with beggars. “These idle people,” says this curious observer, “receive in alms three, four, and even five shillings a day. They have their clubs in the parish of St. Giles’s, where they meet, drink and feed well, read the papers, and talk politics. One of my friends put on one day a ragged coat, and promised a handsome reward to a beggar to introduce him to his club. He found the beggars gay and familiar, and poor only in their rags. One threw down his crutch, another untied a wooden leg, a third took off a grey wig or removed a plaister from a sound eye; then they related their adventures, and planned fresh schemes. The female beggars hire[Pg 379] children for sixpence and sometimes even two shillings a day: a very deformed child is worth four shillings.” In the same parish the pickpockets met to dine and exchange or sell snuff-boxes, handkerchiefs, and other stolen property.

About fifty years before, says Archenholz, there had been a pickpockets’ club in St. Giles’s, where the knives and forks were chained to the table and the cloth was nailed on. Rules were, however, decorously observed, and chairmen chosen at their meetings. Not far from this house was a celebrated gin-shop, on the sign-post of which was written, “Here you may get drunk for a penny, dead drunk for twopence, and straw for nothing.” The cellars of this public-spirited man were never empty.

Archenholz also sketches the conjurors who told fortunes for a shilling. They wore black gowns and false beards, advertised in the newspapers, and painted their houses with magical figures and planetary emblems.[656]

In 1783 Mr. J. T. Smith describes how he made for Mr. Crowle, the illustrator of Pennant, a sketch of Old Simon, a well-known character, who took his station daily under one of the gate piers of the old red and brown brick gateway at the northern end of St. Giles’s Churchyard, which then faced Mr. Remnent’s timber-yard. This man wore several hats, and was remarkable for a long, dirty, yellowish white beard. His chapped fingers were adorned with brass rings. He had several coats and waistcoats—the upper wrap-rascle covering bundles of rags, parcels of books, canisters of bread and cheese, matches, a tinder-box, meat for his dog, scraps from Fox’s Book of Martyrs, and three or four dog’s-eared, thumbed, and greasy numbers of the Gentleman’s Magazine. From these random leaves he gathered much information, which he retailed to persons who stopped to look at him. Simon and his dog lodged under a staircase in an old shattered building in Dyot Street, known as “Rat’s Castle.” It was in this beggars’ rendezvous that Nollekens the sculptor used to seek models for his Grecian Venuses. Rowlandson etched Simon several[Pg 380] times in his usual gross but droll manner.[657] There was also a whole-length print of him published by John Seago, with this monumental inscription—“Simon Edy, born at Woodford, near Thrapston, Northamptonshire, in 1709. Died May 18th, 1783.”

Simon had had several dogs, which, one after the other, were stolen, and sent for sale at Islington, or killed for their teeth by men employed by the dentists. The following anecdote is told of his last and most faithful dog:—Rover had been a shepherd’s dog at Harrow, and having its left eye struck out by a bullock’s horn, was left with Simon by its master, a Smithfield drover. The beggar tied him to his arm with a long string, cured him, and then restored him to the drover. After that, the dog would stop at St. Giles’s porch every market-day on its way after the drover to the slaughter-house in Union Street, and receive caresses from the hand which had bathed its wound. Rover would then yelp for joy and gratitude, and scamper off to get up with the erring bullocks. At last poor Simon missed the dog for several weeks; at the end of that time it appeared one morning at his feet, and with its one sorrowful and uplifted eye implored Simon’s protection by licking his tawny beard. His master the drover was dead. Simon was only too glad to adopt Rover, who eventually followed him to his last home.

There was an elegy printed for good-natured, inoffensive old Simon, with a woodcut portrait attached. The Hon. Daines Barrington is said to have never passed the old mendicant without giving him sixpence.

Mr. J. T. Smith, himself afterwards Curator of the Prints at the British Museum, published some curious etchings of beggars and street characters in 1815. Amongst them are ragged men carrying placards of “The Grand Golden Lottery;” strange old-clothesmen in cocked hats and two-tier wigs; itinerant wood-merchants; sellers of toys, such as “young lambs” or live haddock; flying piemen in pig tails and shorts; women in gipsy hats; door-mat sellers; [Pg 381]vendors of hot peas, pickled cucumbers, lemons, windmills (toys); and, last and least, Sir Harry Dimsdale, the dwarf Mayor of Garratt.

The condition of the beggars of St. Giles in 1815 we gather pretty accurately from the evidence given by Mr. Sampson Stevenson, overseer of the parish, and by trade an ironmonger at No. 11 King Street, Seven Dials, before a committee of the House of Commons, the Right Honourable George Rose in the chair.

Mr. Stevenson’s shop was not more than a few yards from one of the beggars’ chief rendezvous, and he had therefore been enabled to closely study their habits. The inn had lost its licence, as the landlord encouraged thieves; and he had made inquiries of petition-writers, the highest class of mendicants. He had gone frequently into the bar of the Fountain in King Street, another of their haunts, to watch their goings-on. The pretended sailors never carried anything on their backs, as they only begged or extorted money; but the other rogues, who made it their practice to ask for food and clothing, always carried a knapsack to put it in. They returned laden with shoes and clothes, which they would sell in Monmouth Street. They had been heard to say that they had made three or four shillings a day by begging shoes alone.[658] Their mode of obtaining charity was to go barefoot and scarify their heels so that the blood might show. They went out two or three together, or more, and invariably changed their routes each day. Mr. Stevenson had seen them pull out their money and share it. Victuals, he believed, they threw away; but everything else they sold. They would stop at the Fountain till the house closed, or till they got drunk, began to fight, and were turned out by the publican, who feared the losing his licence. They probably went to even lower places to finish their revel.

“They teach other,” he said, “different modes of extortion. They are of the worst character, and overwhelm you with cursing and abuse if you refuse them money. There is[Pg 382] one special rascal, Gannee Manos, who is scarcely three months in the year out of gaol. He always goes barefoot, and scratches his ankles to make them bleed. He is the greatest collector of shoes and clothes, as he goes the most naked to excite compassion.” Another man had been known in the streets for fifteen or twenty years. He generally limped or passed as a cripple; but Mr. Stevenson has seen him fencing and jumping about like a pugilist. He went without a hat, with bare arms, and a canvas bag on his back. He generally began by singing a song, and he carried primroses or something in his hand. He pretended to be scarcely able to move one foot before the other; but if a Bow Street officer or a beadle came in sight, he was off as quick as any one. There was another man, an Irishman who had had a good education, and had been in the medical line; he wrote a beautiful hand, and drew up petitions for beggars at sixpence or a shilling each.

“These men come out by twenties and thirties from the bottom of Dyot Street, and then branch off five or six together. The one who has still some money left starts them with a pint or half a pint of gin. They have all their divisions, and they quarter the town into sections. Some of them collect three, four, or five children, paying sixpence a day for each, and then they go begging in gangs, setting the children crying to excite people’s sympathies. The Irish sometimes have the impudence to bring these children to the board and claim relief, and swear the children are their own. In a short time they are found out; but till the discovery their landlords will swear their story is true. Sometimes, by giving their own country people something, the landlords help to detect them. But even in cases where the children are their own, they will not work when they have once got into the habit of begging. If they will not come into the workhouse, their relief is instantly stopped.

“They spend their evenings drinking, after dining at an eating-house. Deserving people never beg: they are ashamed of it. They do not eat broken victuals. They have seldom any lodgings. There are houses where forty or fifty of them[Pg 383] sleep. A porter stands at the door and takes the money. In the morning there is a general muster to see they have stolen nothing, and then the doors are unlocked. For threepence they have clean straw, for fourpence something more decent, and for sixpence a bed. These are all professional beggars; they beg every day, even Sundays. They will not work; they get more money by begging. Sometimes during hard frosts they pretend to beg for work; but their children are sent out early by their parents to certain prescribed stations to beg, sometimes with a broom. If they do not bring home more or less according to their size, they are beaten. A large family of children is a revenue to these people.”

When beggars did not get enough for their subsistence, Mr. Stevenson believed that they had a fund amongst themselves, as they so seldom applied for relief. The Irish were generally afraid to apply, for fear of being returned to their own country. Beggars had been heard to brag of getting six, seven, and eight shillings a day, or more; and if one got more than the others, he divided it with the rest. Mr. Stevenson concluded his evidence by saying that there were so many low Irish in St. Giles’s, that out of £30,000 a year collected in that parish by poor-rate, £20,000 went to this low and shifting population, that decreased in summer and increased in winter.

From one or two specimens culled from the London newspapers in 1829 we do not augur much improvement in the character and habits of the St. Giles’s beggars. On the 12th of July 1829 John Driscoll, an old professional mendicant, was brought up at the Marylebone Police-office, charged with begging, annoying respectable persons, and even following fashionably dressed ladies into shops. In his pockets were found a small sum of money, some ham sandwiches, and an invitation ticket signed “Car Durre, chairman.” It requested the favour of Mr. Driscoll’s company on Monday evening next, at seven o’clock, at the Robin Hood, Church Street, St. Giles’s, for the purpose of taking supper with others in his line of calling or profession. Mr.[Pg 384] Rawlinson said he supposed that an alderman in chains would grace the beggars’ festive board, but he would at least prevent the prisoner forming one of the party on Monday, and sent him to the House of Correction for fourteen days.[659]

The same day one of those men who chalk “I am starving” on the pavement was also sent to the treadmill for fourteen days. Francis Fisher, the prisoner in question, was one of a gang of forty pavement chalkers. In the evening, “after work,” these men changed their dress, and with their ladies enjoyed themselves over a good supper, brandy and water, and cigars. In the winter time, when they excited more compassion, their average earnings were ten shillings a day. This would make £20 a day for the gang, and no less than £7300 a year.

Monmouth Street is generally supposed to have derived its name from the Duke of Monmouth, Charles II.’s natural son, whose town house stood close by in Soho Square. It was perhaps named from Carey, Earl of Monmouth, who died in 1626, and his son, who died in 1661: they were both parishioners of St. Giles’s.[660] It was early known as the great mart for old clothes, but was superseded in later times by Holy Well Street, which in its turn was displaced by the Minories. Lady Mary Wortley alludes to the lace coats hung up for sale in Monmouth Street like Irish patents. Even Prior, in his pleasant metaphysical poem of “Alma,” says—

“This looks, friend Dick, as Nature had

But exercised the salesman’s trade,

As if she haply had sat down

And cut out clothes for all the town,

Then sent them out to Monmouth Street,

To try what persons they would fit.”

Gay also alludes to this Jewish street in the following distich in his “Trivia”—

“Thames Street gives cheeses, Covent Garden fruits,

Moorfields old books, and Monmouth Street old suits.”

[Pg 385]Most of the shops in Monmouth Street were occupied by Jew dealers in 1849, and horse-shoes were then to be seen nailed under the door-steps of the cellars to scare away witches.[661]

Mr. Charles Dickens in his Sketches by Boz, published in 1836-7, describes Seven Dials and Monmouth Street as they then appeared. The maze of streets, the unwholesome atmosphere, the men in fustian spotted with brickdust or whitewash, and chronically leaning against posts, are all painted by this great artist with the accuracy of a Dutch painter. The writer boldly plunges into the region of “first effusions and last dying speeches, hallowed by the names of Catnach and of Pitts,” and carries us at once into a fight between two half-drunk Irish termagants outside a gin-shop. He then takes us to the dirty straggling houses, the dark chandler’s shop, the rag and bone stores, the broker’s den, the bird-fancier’s room as full as Noah’s ark, and completes the picture with a background of dirty men, filthy women, squalid children, fluttering shuttlecocks, noisy battledores, reeking pipes, bad fruit, more than doubtful oysters, attenuated cats, depressed dogs, and anatomised fowls. Every house has, he says, at least a dozen tenants. The man in the shop is in the “baked jemmy” line, or deals in firewood and hearthstones. An Irish labourer and his family occupy the back kitchen, while a jobbing carpet-beater is in the front. In the front one pair there’s another family, and in the back one pair a young woman who takes in tambour-work. In the back attic is a mysterious man who never buys anything but coffee, penny loaves, and ink, and is supposed to write poems for Mr. Warren.[662]

The Monmouth Street inhabitants Mr. Dickens describes as a peaceable, thoughtful, and dirty race, who immure themselves in deep cellars or small back parlours, and seldom come forth till the dusk and cool of the evening, when, seated in chairs on the pavement, smoking their pipes, they watch the gambols of their children as they revel in the gutter, a happy troop of infantine scavengers.

[Pg 386]“A Monmouth Street laced coat” was a byword a century ago, but still we find Monmouth Street the same. Pilot coats, double-breasted check waistcoats, low broad-brimmed coachmen’s hats, and skeleton suits, have usurped the place of the old attire; but Monmouth Street, said Charles Dickens, is still “the burial-place of the fashions, and we love to walk among these extensive groves of the illustrious dead, and indulge in the speculations to which they give rise.”[663]

In 1816 there were said to be 2348 Irish people resident in St. Giles’s; but an Irish witness before a committee of the House declared there were 6000 Irish, and 3000 children in the neighbourhood of George Street alone. In 1815 there were 14,164 Irish in the whole of London.[664] The Irish portion of the parish of St. Giles’s was known by the name of the Holy Land in 1829.

THE SEVEN DIALS.

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:12:52 GMT