Haunted London, Index

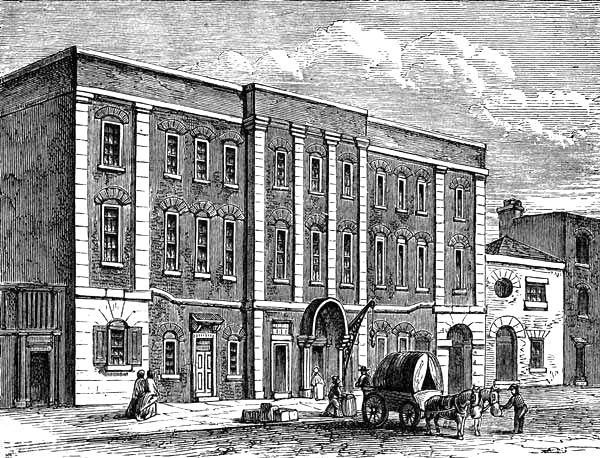

LINCOLN’S INN FIELDS THEATRE, 1821.

CHAPTER XIV.

LINCOLN’S INN FIELDS.

Lincoln’s Inn, originally belonging to the Black Friars before they removed Thames-ward, derives its name from Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, to whom it was given by Edward I., and whose town house or inn stood on the same site in the reign of Edward I. Earl Henry died in 1312, the year in which Gaveston was killed, and his monument was one of the stateliest in the old church. His arms are still those of the inn and of its tributaries, Furnival’s and Thavies inns. There is yet extant an old account of the earl’s bailiff, relating to the sale of the fruit of his master’s garden. The[Pg 388] noble’s table was supplied and the residue sold. The apples, pears, large nuts, and cherries, the beans, onions, garlic, and leeks, produced a profit of £9: 2: 3 (about £135 in modern money). The only flowers were roses. The bailiff, it appears, expended 8s. a year in purchasing small fry, frogs, and eels, to feed the pike in the pond or vivary.[665]

Part of the Chancery Lane side of Lincoln’s Inn was in 1217 and 1272 “the mansion house” of William de Haverhill, treasurer to King Henry III. He was attainted for treason, and his house and lands were confiscated to the king, who then gave his house to Ralph Neville, Chancellor of England and Bishop of Chichester, who built there “a fair house;” and the Bishops of Chichester inhabited it there till Henry VII.’s time, when they let it to law students, reserving lodgings for themselves, and it fell into the hands of Judge Sulyard and other feoffees. This family held it till Elizabeth’s time, when Sir Edward Sulyard, of Essex, sold the estate to the Benchers,[666] who then began enlarging their frontier and building.

The plain Tudor gateway with the two side towers soaked with black smoke, the oldest part of the existing structure, was built in 1518 by Sir Thomas Lovell, a member of this inn and treasurer of the household to Henry VII., when great alterations took place in the inn. What thousands of wise men and rogues have passed under its murky shadow! None of the original building is left. The Black Friars’ House fronted the Holborn end of the Bishop’s Palace.[667] The chambers adjoining the Gate House are of a later date and it was at these that Mr. Cunningham thinks Ben Jonson worked.[668]

The chapel, of debased Perpendicular Gothic, was built by Inigo Jones, and consecrated in 1623, Dr. Donne the poet preaching the consecration sermon. The stained glass was the work of a Mr. Hale of Fetter Lane. The twelve apostles, Moses, and the prophets still glow like immortal[Pg 389] flowers, bright as when Donne, or Ussher, watched the light they shed. One of the windows bears the name of Bernard van Linge, the same man probably who executed the windows at Wadham College, Oxford.[669] Noy, the Attorney-General and creature of Charles I., a friend of Laud, and the proposer of the writ for ship-money, put up the window representing John the Baptist, rather an ominous saint, surely, in Charles’s time. Noy died in 1634, before the storm which would certainly have carried his head off. He left his money to a prodigal son, who was afterwards killed in a duel,—“Left to be squandered, and I hope no better from him,” says the dying man, bitterly. It was Noy who decided the curious case of the three graziers who left their money with their hostess. One of them afterwards returned and ran off with the money; upon which the other two sued the woman, denying their consent. Mr. Noy pleaded that the money was ready to be given up directly the three men came together and claimed it.[670] Rogers tells this story in his poem of “Italy,” and gives it a romantic turn.

Laud, always restless for novelties that could look like Rome, and yet not be Rome, referred to the Lincoln’s Inn windows at his trial. He wondered at a Mr. Brown objecting to such things, considering he was not of Lincoln’s Inn, “where Mr. Prynne’s zeal had not yet beaten down the images of the apostles in the fair windows of that chapel, which windows were set up new long since the statute of Edward VI.; and it is well known,” says that enemy of the Puritans, “that I was once resolved to have returned this upon Mr. Brown in the House of Commons, but changed my mind, lest thereby I might have set some furious spirit at work to destroy those harmless goodly windows, to the just dislike of that worthy society.”[671]

The crypt under the chapel rests on many pillars and strong-backed arches, and, like the cloisters in the Temple, was intended as a place for student-lawyers to walk in and exchange learning. Butler describes witnesses of the [Pg 390]straw-bail species waiting here for customers,[672] just as half a century ago they used to haunt the doors of Chancery Lane gin-shops. On a June day in 1663 Pepys came to walk under the chapel by appointment, after pacing up and down and admiring the new garden then constructing.

The great Sir Thomas More, Chancellor of England in Henry VIII.’s time, had chambers at Lincoln’s Inn when he was living in Bucklersbury after his marriage. This was about 1506. He wrote his Utopia in 1516. King Henry grew so fond of More’s learned and witty conversation, that he used to constantly send for him to supper, and would walk in the garden at Chelsea with his arm round his neck. More was beheaded in 1535 for refusing to take the oath of succession and acknowledge the legality of the king’s divorce from Catherine of Arragon. Erasmus, who knew More well, inscribed the “Nux” of Ovid to his son. More’s skull is still preserved, it is said, in the vault of St. Dunstan’s Church at Canterbury.[673] More’s daughter, Margaret Roper, was buried with it in her arms.

Dr. Donne, the divine and poet, whose mother was distantly related to Sir Thomas More and to Heywood the epigrammatist, was a student at Lincoln’s Inn in his seventeenth year, but left it to squander his father’s fortune. He was a friend of Bacon, with whom he lived for five years, and also of Ben Jonson, who corresponded with him. When young, Donne had written a thesis to prove that suicide is no sin. “That,” he used to say in later years, “was written by Jack Donne, not by Dr. Donne.”

This same poet was for two years preacher at Lincoln’s Inn; so was the charitable and amiable Tillotson in 1663. The latter, after preaching the doctrine of non-resistance before King Charles II., was nicknamed “Hobbes in the pulpit;” he and Dr. Burnet both tried in vain to force the same doctrine on Lord William Russell when he was preparing for death. Tillotson, who was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1691 by King William, was a valued friend[Pg 391] of Locke. Addison considered Tillotson’s three folio volumes of sermons to be the standard of English, and meant to make them the ground-work of a dictionary which he had projected. Warburton, a sterner critic, denies that the sermons are oratorical like Jeremy Taylor’s, or thoughtful like Barrow’s, but yet confesses them to be clear, rational, equable,[674] and certainly not without a noble simplicity.

Among the most eminent students of Lincoln’s Inn we must remember Sir Matthew Hale. After a wild and vain youth, Hale suddenly commenced studying sixteen hours a day,[675] and became so careless of dress that he was once seized by a pressgang. The sight of a friend who fell down in a fit from excessive drinking led to this honest man’s renouncing all revelry and becoming unchangeably religious. Noy directed him in his studies; he became a friend of Selden, and was one of the counsel for Strafford, Laud, and the king himself. Nevertheless, he obtained the esteem of Cromwell, who was tolerant of all shades of goodness. He died 1675-6. When a nobleman once complained to Charles II. that Hale would not discuss with him the arguments in his cause then before him, Charles replied, “Ods fish, man! he would have treated me just the same.”

Lord Chancellor Egerton, afterwards Lord Ellesmere, was of Lincoln’s Inn. His son became Earl of Bridgewater. He was a friend of Lord Bacon, and had a celebrated dispute with Chief Justice Coke as to whether “the Chancery can relieve by subpœna after a judgment at law in the same cause.” Prudent, discreet, and honest, Ellesmere was esteemed by both Elizabeth and James, and died at York House in 1617. Bishop Hacket says of him that “He neither did, spoke, nor thought anything in his life but what deserved praise.”[676] It is said that many persons used to go to the Chancery Court only to see and admire his venerable presence.

Sir Henry Spelman was admitted of Lincoln’s Inn. He was a friend of Dugdale, and one of our earliest students of[Pg 392] Anglo-Saxon. He wrote much on civil law, sacrilege, and tithes. Aubrey tells us that he was thought a dunce at school, and did not seriously sit down to hard study till he was about forty. This eminent scholar died in 1641, and was interred with great solemnity in Westminster Abbey.

Shaftesbury, the subtle and dangerous, and one of the restorers of the king he afterwards worked so hard to depose, was of Lincoln’s Inn.

Ashmole, the great herald, antiquary, and numismatist, originally a London attorney, was married in Lincoln’s Inn Chapel, in 1668, to the daughter of his great colleague in topography and heraldry, Sir William Dugdale, the part compiler of the Monasticon.

In the chapel was buried Alexander Brome, a Royalist attorney, a translator of Horace, and a great writer of sharp songs against “The Rump,” who died in 1666. Here also—in loving companionship with him only because dead—rests that irritable Puritan lawyer, William Prynne. He twice lost an ear in the pillory, besides being branded on the cheek. He ultimately opposed Cromwell and aided the return of Charles, for which he was made Keeper of the Tower Records. His works amount to forty folio and quarto volumes. He left copies of them to the Lincoln’s Inn library. Needham calls him “the greatest paper-worm that ever crept into a library.” He died in his Lincoln’s Inn chambers in 1669. Wood computes that Prynne wrote as much as would amount to a sheet for every day of his life. His epitaph had been erased when Wood wrote the Athenæ Oxonienses in 1691.

In the same chapel lies Secretary Thurloe, the son of an Essex rector and the faithful servant of Cromwell. He was admitted of Lincoln’s Inn in 1647, and in 1654 was chosen one of the masters of the upper bench. He died suddenly in his chambers in Lincoln’s Inn in 1668. Dr. Birch published several folio volumes of his State Papers. He seems to have been an honest, dull, plodding man. Thurloe’s chambers were at No. 24 in the south angle of the great court leading out of Chancery Lane, formerly called the[Pg 393] Gatehouse Court, but now Old Buildings—the rooms on the left hand of the ground-floor. Here Thurloe had chambers from 1645 to 1659. Cromwell must have often come here to discuss dissolutions of Parliament and Dutch treaties. State papers sufficient to fill sixty-seven folio volumes were discovered in a false ceiling in the garret by a clergyman who had borrowed the chambers of a friend during the long vacation. He disposed of them to Lord Chancellor Somers.[677] Cautious old Thurloe had perhaps sown these papers, hoping to reap the harvest under some new Cromwellian dynasty that never came.

Rushworth the historian was a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn. During the Civil Wars he was assistant clerk to the House of Commons. After the Restoration he became secretary to the Lord Keeper, but falling into distress, died in the King’s Bench in 1690. His eight folio volumes of Historical Collections are specially valuable.[678]

Sir John Denham also studied in this pasturing-ground of English genius; and here, after squandering all his money in gaming, he wrote an essay upon the vice that brings its own punishment. In 1641, when his tragedy of “The Sophy” appeared, Waller said that Denham had broken out like the Irish rebellion, threescore thousand strong. In 1643 appeared his “Cooper’s Hill” which the lampooners declared the author had bought of a vicar for forty pounds.[679] He became mad for a short time at the close of life, and was then ridiculed by Butler, so says Dr. Johnson. He died in 1668, and was interred in Westminster Abbey. Denham and Waller smoothed the way for Dryden,[680] and founded the Pope school of highly polished artificial verse. Denham’s noble apostrophe to the river Thames is all but perfect.

George Wither, one of our fine old poets of a true school, rougher but more natural than Denham’s, the son of a Hampshire farmer, entered at Lincoln’s Inn. Sent to the Marshalsea for his just but indiscreet satires, he turned soldier, fought against the Royalists, and became one of[Pg 394] Cromwell’s dreaded major-generals. He was in Newgate for a long time after the Restoration, and died in 1667. When taken prisoner by Charles, Sir John Denham obtained his release on the humorous pretext that, while Wither lived, he (Denham) would not be the worst poet in England.[681]

In No. 1 New Square, Arthur Murphy, the friend of Dr. Johnson, resided for twenty-three years. He became a member of the inn in 1757. In 1788 he sold his chambers, and retired from the bar. As a journalist he was ridiculed by Wilkes and Churchill. His plays, “The Grecian Daughter” and “Three Weeks after Marriage,” were successful. He also translated Tacitus and Sallust. He died in 1805.[682]

Judge Fortescue, a great English lawyer of the time of Henry VI., was a student of this inn. He wrote his great work, De Laudibus Legum Angliæ to educate Prince Edward when in banishment in Lorraine. This pious, loyal, and learned man, after being nominal Chancellor, returned to retirement in England, and acknowledged Edward IV.

The Earl of Mansfield belonged to the same illustrious inn. For elegance of mind, for honesty and industry, and for eloquence, he stands unrivalled. The proceedings against Wilkes, and the destruction of his house in Bloomsbury by the fanatical mob of 1780, were the chief events of his useful life.

Spencer Perceval was of Lincoln’s Inn. A son of the Earl of Egmont, he became a student here in 1782. In Parliament he supported Pitt and the war against Napoleon. In 1801, under the Addington ministry, he became Attorney-General, and persecuted Peltier for a libel on Bonaparte during the peace of Amiens. On the death of the Duke of Portland he was raised to the head of the Treasury, where he continued till May 1812, when he was shot through the heart in the lobby of the House of Commons by Bellingham, a bankrupt merchant of Archangel, who considered himself aggrieved because ministers had not taken his part and claimed redress for his losses from[Pg 395] the Russian Government. Perceval was a shrewd, even-tempered lawyer, fluent and industrious, who, had time been permitted him, might possibly have proved more completely than he did his incapacity for high ministerial command.

George Canning became a student at Lincoln’s Inn in 1781. His father was a bankrupt wine-merchant who died of a broken heart. His mother was a provincial actress. His relation, Sheridan, introduced him to Fox, Grey, and Burke, the latter of whom, it is said, induced him to make politics his profession. He made his maiden speech, attacking Fox and supporting Pitt, in 1794. Late in life he gradually began to support some liberal measures. In 1827 he became First Lord of the Treasury, and died a few months afterwards in the zenith of his power.

Lord Lyndhurst was also one of the glories of this inn. The trial of Dr. Watson for treason, in 1817, first gained for this son of an American painter a reputation which, joined with his prudent conduct in the trial of Cashman the rioter led to his being appointed Solicitor-General in 1818. From that he rose in rapid succession, to the posts of Attorney-General, Master of the Rolls, Lord Chancellor, and Lord Lyndhurst. Old, eccentric, “irrepressible” Sir Charles Wetherell was Copley’s fellow-advocate in Watson’s case, that ended in the prisoner’s acquittal.[683] In 1827, when Abbott became Lord Tenterden, Copley accepted the Great Seal, displacing Lord Eldon, and joined Canning’s cabinet, becoming Lord Lyndhurst. In 1830 he became Chief Baron of the Exchequer.

Charles Pepys, Lord Cottenham, born 1781, was called to the bar by the Society of Lincoln’s Inn in 1804. He was appointed King’s Counsel in 1826, was made Solicitor-General in 1834, succeeded Sir John Leach as Master of the Rolls in the same year, and was elevated to the woolsack in 1836. This Chancellor, who was a very excellent lawyer, was descended from a branch of the family of Samuel Pepys, author of the celebrated Diary.

[Pg 396]Sir E. Sugden was a member of Lincoln’s Inn. He was born in the year 1781. He was the son of a Westminster hairdresser who became rich by inventing a substitute for hair-powder. He was created Lord St. Leonards on the formation of a Conservative ministry in 1852, when he accepted the Great Seal.

Lord Brougham also studied in Lincoln’s Inn. He was born in 1778, and started the Edinburgh Review in 1802. In 1820 he defended Queen Caroline; but it would take a volume to follow the career of this impetuous and versatile genius. His struggles for law-reform, for Catholic emancipation, for abolition of slavery, for the education of the people, and for Parliamentary reform, are matters of history. In his old age, though still vigorous, Lord Brougham grew tamer, and condemned the armed emancipation of slaves practised by the Northern States in the present American war. He died at his residence at Cannes in the South of France in 1868.

Cottenham and Campbell were students in Lincoln’s Inn; so was that eccentric reformer Jeremy Bentham, who was called to the bar in 1722, and was the son of a Houndsditch attorney; and so was Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania.

That “luminary of the Irish Church,”[684] Archbishop Ussher, was preacher at Lincoln’s Inn in 1647, the society giving the good man handsome rooms ready furnished. He continued to preach there for eight years, till his eyesight began to fail. He died in 1655, and was buried, by Cromwell’s permission, with great magnificence, in Erasmus’s chapel in Westminster Abbey. His library of 10,000 volumes, bought of him by Cromwell’s officers, was given by Charles II. to Dublin College. Ussher, when only eighteen, was the David who discomfited in public dispute the learned Jesuit Fitz-Simons. He saw Charles beheaded from the roof of a house on the site of the Admiralty.

Dr. Langhorne, the joint translator with his brother of the Lives of Plutarch, was assistant preacher at Lincoln’s Inn.[Pg 397] An imitator of Sterne, and a writer in Griffiths’s Monthly Review, he was praised by Smollett and abused by Churchill. Langhorne’s amiable poem, The Country Justice, was praised by Scott. He died in 1779.

That fiery controversialist Warburton was preacher at Lincoln’s Inn in 1746, and the same year preached and published a sermon on the Highland rebellion. He was the son of an attorney at Newark-upon-Trent. His Divine Legation was an effort to show that the absence of allusions in the writings of Moses to a system of rewards and punishments was a proof of their divine origin. The book is full of perverse digressions. His edition of Shakspere is, perhaps, to use a fine expression of Burke, “one of the poorest maggots that ever crept from the great man’s carcase.” Pope left half his library to Warburton, who had suggested to him the conclusion of the Dunciad. Wilkes, Bolingbroke, Dr. Louth, and Churchill were all by turns attacked by this arrogant knight-errant. Warburton died in 1779.

Reginald Heber, afterwards the excellent Bishop of Calcutta, was appointed preacher at Lincoln’s Inn in 1822, the year before he sailed for India. In 1826 this good man was found dead in his bath at Trichinopoly. The sudden death of this energetic missionary was a great loss to East Indian Christianity. In the “company of the preachers” we must not forget the excellent Dr. Van Mildert, afterwards Bishop of Durham, and Dr. Thomson the present Archbishop of York.

In the old times the Lord Chancellor held his sittings in the great hall of Lincoln’s Inn. Here, too, at the Christmas revels, the King of the Cockneys administered his laws. Jack Straw, a sort of rebellious rival, was put down, with all his adherents, as a bad precedent for the Essexes and Norfolks of the inn, by wary Queen Elizabeth, who always kept a firm grip on her prerogative. In the same reign absurd sumptuary laws, vainly trying to fix the quicksilver of fashion, forbade the students to wear long hair, long beards, large ruffs, huge cloaks, or big spurs. The fine for wearing a beard of more than a fortnight’s[Pg 398] growth was three shillings and fourpence.[685] In her father’s time beards had been prohibited under pain of double commons.

In the old hall, replaced by the new Tudor building, stood one of Hogarth’s most pretentious but worst pictures, “Paul preaching before Felix,” an ill-drawn and ludicrous caricature of epic work. The society paid for it. It is now rolled up and hid away with as much contumely as Kent’s absurdity at St. Clement’s when Hogarth parodied it.

The new hall of Lincoln’s Inn was built by Mr. P. Hardwick, the architect of the St. Katherine Docks, and was opened by the Queen in person in 1845. It is a fine Tudor building of red brick, with stone dressings. The hall is 120 feet, the library 80 feet long. The contract was taken for £55,000, but its cost exceeded that sum. The library contains the unique fourth volume of Prynne’s Records, which the society bought for £335 at the Stow sale in 1849, and all Sir Matthew Hale’s bequests of books and MSS.: “a treasure,” says that “excellent good man,” as Evelyn calls him[686] in his will, “that is not fit for every man’s view.” The hall contains a fresco representing the “Lawgivers of the World,” by Watts. The gardens were much curtailed by the erection of the hall, and their quietude destroyed. Ben Jonson talks of the walks under the elms.[687] Steele seems to have been fond of this garden when he felt meditative. In May 1709, he says much hurry and business having perplexed him into a mood too thoughtful for company, instead of the tavern “I went into Lincoln’s Inn Walk, and having taken a round or two, I sat down, according to the allowed familiarity of these places, on a bench.” In a more thoughtful month (November) of the same year he goes again for a solitary walk in the garden, “a favour that is indulged me by several of the benchers, who are very intimate friends, and grown old in the neighbourhood.” It was this bright frosty night, when the whole body of air had been purified into “bright [Pg 399]transparent æther,” that Steele imagined his vision of “The Return of the Golden Age.”

Brave old Ben Jonson was the son of a Scotch gentleman in Henry VIII.’s service, who, impoverished by the persecutions of Queen Mary, took orders late in life. His mother married for the second time a small builder or master bricklayer. He went to Westminster school, where Camden, the great antiquary, was his master. A kind patron sent him to Cambridge.[688] He seems to have left college prematurely, and have come back to London to work with his father-in-law.[689]

There is an old tradition that he worked at the garden-wall of Lincoln’s Inn next to Chancery Lane, and that a knight or bencher (Sutton, or Camden), walking by, hearing him repeat a passage of Homer, entered into conversation with him, and finding him to have extraordinary wit, sent him back to college; or, as Fuller quaintly puts it, “some gentlemen pitying that his parts should be buried under the rubbish of so mean a calling, did by their bounty manumise him freely to follow his own ingenious inclinations.”[690]

Gifford sneers at the story, for the poet’s own words to Drummond of Hawthornden were simply these:—“He could not endure the occupation of a bricklayer,” and therefore joined Vere in Flanders, probably going with reinforcements to Ostend in 1591-2.[691] He there fought and slew an enemy, and stripped him in sight of both armies. On his return, he became an actor at a Shoreditch theatre. His enemies, the rival satirists, frequently sneer at the quondam profession of Ben Jonson, and describe him stamping on the stage as if he were treading mortar. For myself, I admire brave, truculent old Ben, and delight even in his most crabbed and pedantic verse, and therefore never pass Lincoln’s Inn garden without thinking of Shakspere’s honest but rugged friend—“a bear only in the coat.”

On June 27, 1752, there was a dreadful fire in New[Pg 400] Square, which destroyed countless historical treasures, including Lord Somers’s original letters and papers.

At No. 2 and afterwards at No. 6 New Square, Lincoln’s Inn, which is built on Little Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and forms no part of the Inn of court, lived Sir Samuel Romilly. This “great and amiable man,” as Tom Moore calls him, killed himself in a fit of melancholy produced by overwork joined to the loss of his wife, “a simple, gay, unlearned woman.” Sir Samuel was a stern, reserved man, and she was the only person in the world to whom he could unbosom himself. When he lost her, he said, “the very vent of his heart was stopped up.”[692]

It was in Old Square, Lincoln’s Inn, that Benjamin Disraeli, born in December 1805, much too erratic for Plowden and Coke, used to come to study conveyancing at the chambers of Mr. Bassevi. He is described as often arriving with Spenser’s Faerie Queen under his arm, stopping an hour or two to read, and then leaving. This led, as might be expected, not to the woolsack but to the authorship of Coningsby. His Premiership and his Patent of Peerage as Lord Beaconsfield, are due to other causes.

Whetstone Park, now a small quiet passage, full of printing-offices and stables, between Great Turnstile and Gate Street, derived its name from a vestryman of the time of Charles I. It is now chiefly occupied by mews, but was once filled by infamous houses and low brandy-shops.

In 1671, the Duke of Monmouth, the Duke of Grafton, and the Duke of St. Alban’s, three of King Charles II.’s illegitimate sons, killed here a beadle in a drunken brawl. A street-ballad was written on the occasion, more full of spite against the corrupt court than of sympathy with the slain man. In poor doggerel the Catnach of 1671 describes the watch coming in, disturbed from sleep, to appease their graces—

“Straight rose mortal jars,

’Twixt the night blackguard and (the) silver stars;

Then fell the beadle by a ducal hand,

For daring to pronounce the saucy ‘Stand!’”

[Pg 401]Sadly enough, the silly fellow’s death led to a dance at Whitehall being put off,—

“Disappoints the queen, ‘poor little chuck!’”[693]

and all the brisk courtiers in their gay coats bought with the nation’s subsidies.

The last two lines are vigorous, sarcastic, and worthy of a humble imitator of Dryden. The poet sums up—

“Yet shall Whitehall, the innocent and good,

See these men dance, all daubed with lace and blood.”

In 1682 the misnamed “Park” grew so infamous, that a countryman, having been decoyed into one of the houses and robbed, went into Smithfield and collected an angry mob of about 500 apprentices, who marched on Whetstone Park, broke open the houses, and destroyed the furniture. The constables and watchmen, being outnumbered, sent for the king’s guard, who dispersed them and took eleven of them. Nevertheless, the next night another mob stormed the place, again broke in the doors, smashed the windows, and cut the feather-beds to pieces.

Lincoln’s Inn Fields formed part of the ancient Fickett’s Fields, a plot of ground of about ten acres, extending formerly from Bell Yard to Portugal Street and Carey Street. It seems to have been used in the Middle Ages for jousts and tournaments by the Templars and Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, to the priory of which last order it belonged till Henry VIII. dissolved the monasteries, when it was granted to Anthony Stringer. In an inquest of the time of James I. it is described as having two gates for horses and carriages at the east end—one gate leading into Chancery Lane, the other gate at the western end.[694]

Queen Elizabeth, afraid that London was growing unwieldly, issued several proclamations against further building. James I., still more timid and conservative, and not thoroughly acquainted with his own capital, issued a like absurd ukase in 1612, by the desire of the benchers and[Pg 402] students of Lincoln’s Inn, forbidding the erection of new houses in these fields. But no royal edict can prevent a demand for creating a supply, and as the building still went on, a commission was appointed in 1618 to lay out the square in a regular plan. Bacon, then Lord Chancellor, and many noblemen, judges, and masters in Chancery, were on this commission, and Inigo Jones, the king’s Surveyor-General, drew up the scheme. The report of this body, given by Rymer, sets out that in the last sixteen years there had been more building near and about the City of London than in ages before, and that as these fields were much surrounded by the dwellings and lodgings of noblemen and gentlemen of quality, “all small cottages and closes shall be paid for and removed, and the square shall be reduced,” both for sweetness, uniformity, and comeliness, as an ornament to the City, and for the health and recreation of the inhabitants, into walks and partitions, as Mr. Inigo Jones should in his map devise.[695]

There is a tradition that the area of the square, according to Inigo Jones’s plan, was to have been made the exact dimensions of the base of the great pyramid of Geezeh. The tradition is probably true, for the area of the pyramid is 535,824 square feet, and that of Lincoln’s Inn Fields 550,000.[696] The height of the pyramid was 756 feet.

The plan proved too costly, and the subscriptions began probably to fail; but in the course of time noblemen and others began to build for themselves, but without much regard to uniformity.

The elevation of Inigo’s plan for the Fields, painted in oil colours, is still preserved at Wilton House, near Salisbury. The view is taken from the south, and the principal feature in the elevation is Lindsey House in the centre of the west side, whose stone façade, still existing, stands boldly out from the brick houses which support it on either side. The internal accommodation of Lindsey House was never good.[697]

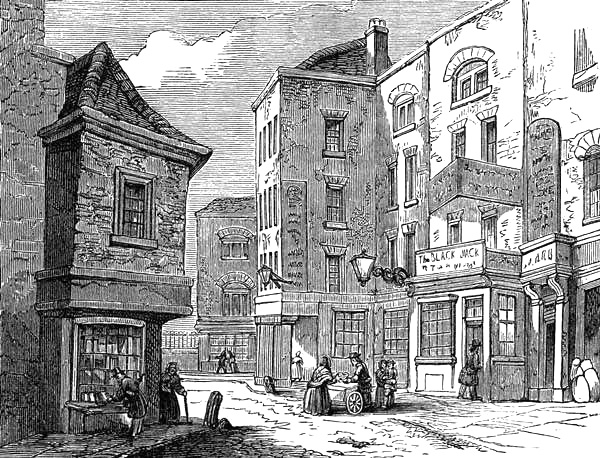

[Pg 403]These fields in Charles I.’s time became the haunt of wrestlers, bowlers, beggars, and idle boys; and here, in 1624, Lilly the astrologer, then servant to a mantua-maker in the Strand, spent his time in bowling with Wat the cobbler, Dick the blacksmith, and such idle apprentices. Hither, after the Restoration, came every sort of villain—the Rufflers, or maimed soldiers, who told lies of Edgehill and Naseby, and who surrounded the coaches of charitable lords; “Dommerers,” or sham dumb men; “Mumpers,” or sham broken gentlemen; “Whipjacks,” or sham seamen with bound-up legs; “Abram-men,” or sham idiots; “Fraters,” or rogues with forged patents; “Anglers,” wild rogues, “Clapper-dudgeons,”[698] and men with gambling wheels of fortune.

In Queen Anne’s reign Gay sketches the dangers of night in these fields; he warns his readers to avoid the lurking thief, by day a beggar, or else—

“The crutch, which late compassion moved, shall wound

Thy bleeding head, and fell thee to the ground.

Nor trust the linkman,” he adds, “along the lonely wall, or he’ll put out his light and rob you, but—

“Still keep the public streets where oily rays

That from the crystal lamp o’erspread the ways.”

The south side of Lincoln’s Inn Fields was built and named three years before the Restoration, by Sir William Cowper, James Cowper, and Robert Henley. In 1668 Portugal Row, as it was called, but not from Charles’s queen,[699] was extremely fashionable. There were then living here such noble and noted persons as Lady Arden, William Perpoint, Esq., Sir Charles Waldegrave, Lady Fitzharding, Lady Diana Curzon, Serjeant Maynard, Lord Cardigan, Mrs. Anne Heron, Lady Mordant, Richard Adams, Esq., Lady Carr, Lady Wentworth, Mr. Attorney Montagu, Lady Coventry, Judge Welch, and Lady Davenant.[700]

[Pg 404]Mr. Serjeant Maynard was the brave old Presbyterian lawyer, then eighty-seven, who replied to the Prince of Orange, when he said that he must have outlived all the men of law of his time—“Sir, I should have outlived the law itself had not your highness come over.”

Lady Davenant was the widow of Sir William Davenant, the Oxford innkeeper’s son, the poet and manager, who, aided by Whitlocke and Maynard, was allowed in Cromwell’s time to perform operas at a theatre in Charterhouse Square. After the Restoration he had the theatre in Portugal Street. He died in 1668, insolvent. His poems were published by his widow, and dedicated to the Duke of York in 1673.

Lord Cardigan was the father of the infamous Countess of Shrewsbury, who is said, disguised as a page, to have held her lover the Duke of Buckingham’s horse while he killed her husband in a duel near Barn Elms. The Earl of Rochester lived in the house next the Duke’s Theatre,[701] which stood behind the present College of Surgeons, as Davenant says in one of his epilogues—

“The prospect of the sea cannot be shown,

Therefore be pleased to think that you are all

Behind the row which men call Portugal.”

In September 1586 Ballard, Babington, and other conspirators against the life of Queen Elizabeth were put to death in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Babington was a young man of good family, who had been a page to the Earl of Shrewsbury, and had plotted to rescue Mary and assassinate Elizabeth. His plot discovered, he had fled to St. John’s Wood for concealment. Seven of these plotters were hanged on the first day, and seven on the second. The last seven were allowed to die, by special grace, before being disembowelled by the executioner.

It was through these fields that, one spring night in 1676-7, Thomas Sadler, an impudent and well-known thief, rivalling the audacity of Blood, having with some confederates stolen the mace and purse of Lord Chancellor Finch from his house in Great Queen Street, bore them in[Pg 405] mock procession on their way to their lodgings in Knightrider Street, Doctors’ Commons. Sadler was hanged at Tyburn for this theft.

Lord William Russell was son of William, Earl of Bedford, by Lady Ann Carr, daughter of Carr, Earl of Somerset. He was beheaded in the centre of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, July 21, 1683, the last year but two of the reign of King Charles II., for being, as it was alleged, engaged in a plot to attack the guards and kill the king, on his return from Newmarket races, at the Rye House Farm, in a by-road near Hoddesdon in Hertfordshire, about seventeen miles north-east of London.

The Whig party, in their eagerness to restrain the Papists and exclude the Duke of York from the throne, had gone too far, and their zeal for the Dissenters had produced a violent reaction in the High Church party. Charles and the Duke, taking advantage of the return tide, began to persecute the Dissenters, denounce Shaftesbury, assail the liberties of the City, and finally dissolved the Parliament. Soon after this, that subtle politician, Shaftesbury, finding it impossible to rouse the Duke of Monmouth, Essex, or Lord Russell, denounced them all as sold and deceived, and fled to Holland.

After his flight, meetings of his creatures were held at the chambers of one West, an active talking man. Keeling, a vintner of decaying business, betrayed the plot, as also did Lord Howard, a man so infamous that Charles himself said “he would not hang the worst dog he had upon his evidence.” Keeling and his brother swore that forty men were hired to intercept the king, but that a fire at Newmarket, which had hastened Charles’s return, had defeated their plans. Goodenough, an ex-sheriff, had told them that the Duke of Monmouth and other great men were to raise 4000 soldiers and £20,000. The brothers also swore that Goodenough had told them that Lord Russell had joined in the design of killing the king and the duke.

Lord Russell acted with great composure. He would not fly, refused to let his friends surrender themselves to[Pg 406] share his fortunes, and told an acquaintance that “he was very sensible he should fall a sacrifice.”[702] When he appeared at the council, the king himself said that “nobody suspected Lord Russell of any design against his own person, but that he had good evidence of his being in designs against his government.” The prisoner denied all knowledge of the intended insurrection, or of the attempt to surprise the guards.

The infamous Jeffries was one of the counsel for his prosecution. Lord Russell argued at his trial, that, allowing he had compassed the king’s death, which he denied, he had been guilty only of a conspiracy to levy war, which was not treason except by a recent statute of Charles II., the prosecutions upon which were limited to a certain time, which had elapsed,[703] so that both law and justice were in this case violated.

The truth seems to be that Lord Russell was a true patriot, of a slow and sober judgment, a taciturn, good man, of not the quickest intelligence, who had allowed himself to listen to dangerous and random talk for the sake of political purposes. He wished to debar the duke from the throne, but he had never dreamt of accomplishing his purpose by murder. It has since been discovered that Sidney, doing evil that good might come, had accepted secret-service money from France, and that Russell himself had interviews with French agents. Lord John Russell explains away this charge very well. Charles was degraded enough to take money from France. The patriots, told that Louis XIV. wished to avoid a war, intrigued with the French king to maintain peace, fearing that if Charles once raised an army under any pretence, he would first employ it to obtain absolute power at home, which it is most probable he would have done.[704] On the whole, these disingenuous interviews must be lamented; they could not and they did not lead to good. It has been justly regretted also that Lord Russell[Pg 407] on his trial did not boldly denounce the tyranny of the court, and show the necessity that had existed for active opposition.

After sentence the condemned man wrote petitions to the king and duke, which were unjustly sneered at as abject. They really, however, contain no promise but that of living beyond sea and meddling no more in English affairs. Of one of them at least, Burnet says it was written at the earnest solicitation of Lady Rachel; and Lord Russell himself said, with regret, “This will be printed and sold about the streets as my submission when I am led out to be hanged.” He lamented to Burnet that his wife beat every bush and ran about so for his preservation; but he acquiesced in what she did when he thought it would be afterwards a mitigation of her sorrow.

When his brave and excellent wife, the daughter of Charles I.’s loyal servant, Southampton, who was the son of Shakspere’s friend, begged for her husband’s life, the king replied, “How can I grant that man six weeks, who would not have granted me six hours?”[705]

There is no scene in history that “goes more directly to the heart,” says Fox, “than the story of the last days of this excellent man.” The night before his death it rained hard, and he said, “Such a rain to-morrow will spoil a great show,” which was a dull thing on a rainy day. He thought a violent death only the pain of a minute, not equal to that of drawing a tooth; and he was still of opinion that the king was limited by law, and that when he broke through those limits, his subjects might defend themselves and restrain him.[706] He then received the sacrament from Tillotson with much devotion, and parted from his wife with a composed silence; as soon as she was gone he exclaimed, “The bitterness of death is past,” saying what a blessing she had been to him, and what a misery it had been if she had tried to induce him to turn an informer. He slept soundly that night and rose in a few hours, but would take no care in[Pg 408] dressing. He prayed six or seven times by himself, and drank a little tea and some sherry. He then wound up his watch, and said, “Now I have done with time and shall go into eternity.” When told that he should give the executioner ten guineas, he said, with a smile, that it was a pretty thing to give a fee to have his head cut off. When the sheriffs came at ten o’clock, Lord Russell embraced Lord Cavendish, who had offered to change clothes with him and stay in his place in prison, or to attack the coach with a troop of horse and carry off his friend; but the noble man would not listen to either proposal.

In the street some in the crowd wept, while others insulted him. He said, “I hope I shall quickly see a better assembly.” He then sang, half to himself, the beginning of the 149th Psalm. As the coach turned into Little Queen Street, he said, looking at his own house, “I have often turned to the one hand with great comfort, but now I turn to this with greater,” and then a tear or two fell from his eyes. As they entered Lincoln’s Inn Fields he said, “This has been to me a place of sinning, and God now makes it the place of my punishment.” When he came to the scaffold, he walked about it four or five times: then he prayed by himself, and also with Tillotson; then he partly undressed himself, laid his head down without any change of countenance, and it was cut off in two strokes. Lord William’s walking-stick and a cotemporary account of his death are kept at Woburn Abbey.

Lady Rachel Russell, the excellent wife of this patriot, had been his secretary during the trial. She spent her after-life, not in unwisely lamenting the inevitable past, but in doing good works, and in educating her children. Writing two months after the execution to Dr. Fritzwilliams, this noble woman says:[707] “Secretly, my heart mourns and cannot be comforted, because I have not the dear companion and sharer of all my joys and sorrows. I want him to talk with, to walk with, to eat and sleep with. All these things are irksome to me now; all company and meals I could avoid,[Pg 409] if it might be.... When I see my children before me, I remember the pleasure he took in them: this makes my heart shrink.”

In 1692 Lady Russell appears to have regained her composure. But she had other trials in store: for in 1711 she lost her only son, the Duke of Bedford, in the flower of his age, and six months afterwards one of her daughters died in childbed.

It is said that, in his hour of need, James II. was mean enough to say to the Duke of Bedford, “My lord, you are an honest man, have great credit, and can do me signal service.” “Ah, sir,” replied the duke, with a grave severity, “I am old and feeble now, but I once had a son.”

The Sacheverell riots culminated in these now quiet Fields. In 1710 Daniel Dommaree, a queen’s waterman, Francis Willis, a footman, and George Purchase, were tried at the Old Bailey for heading a riot during the Sacheverell trial and pulling down meeting-houses. This Sacheverell was an ignorant, impudent incendiary, the adopted son of a Marlborough apothecary, and was impeached by the House of Commons for preaching at St. Andrew’s, Holborn, sermons denouncing the Revolution of 1688. His sermons were ordered to be burnt, and he was sentenced to be suspended for three years. Atterbury helped the mischievous firebrand in his ineffectual defence, and Swift wrote a most scurrilous letter to Bishop Fleetwood, who had lamented the excesses of the mob. Sacheverell had been at Oxford with Addison, who inscribed a poem to him. During the trial, a mob marched from the Temple, whither they had escorted Sacheverell, pulled down Dr. Burgess’s meeting-house, and threw the pulpit, sconces, and gallery pews into a fire in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, some waving curtains on poles, shouting, “High Church standard!” “Huzza! High Church and Sacheverell!” “We will have them all down!” They also burnt other meeting-houses in Leather Lane, Drury Lane, and Fetter Lane, and made bonfires of the woodwork in the streets. They were eventually dispersed by the horse-grenadiers and horse-guards and foot. [Pg 410]Dommaree was sentenced to death, but pardoned; Willis was acquitted; and Purchase was pardoned.[708]

Wooden posts and rails stood round the Fields till 1735, when an Act was passed to enable the inhabitants to make improvements, to put an iron gate at each corner, and to erect dwarf walls and iron palisades.[709] Before this time grooms used to break in horses on this spot. One day while looking at these centaurs, Sir Joseph Jekyll, who had brought a very obnoxious bill into Parliament in 1736 in order to raise the price of gin, was mobbed, thrown down, and dangerously trampled on. His initials, “J. J.,” figure under a gibbet chalked on a wall in one of Hogarth’s prints.[710] Macaulay’s History contains a very highly coloured picture of these Fields. A comparison of the passage with the facts from which it is drawn would be a useful lesson to all historical students who love truth in its severity.[711]

Newcastle House stands at the north-west angle of the Fields, at the south-eastern corner of Great Queen Street. It derived its name from John Holles, Duke of Newcastle, a relative of the noble families of Vere, Cavendish, and Holles. This duke bought the house before 1708, but died in 1711 without issue, and was succeeded in the house by his nephew, the leader of the Pelham administration under George II.

The house had been bought by Lord Powis about 1686. It was built for him by Captain William Winde, a scholar of Webbe’s, the pupil and executor of Inigo Jones.[712] William Herbert, first Marquis of Powis, was outlawed and fled to St. Germain’s to James II., who made him Duke of Powis. Government had thought of buying the house when it was inhabited by the Lord Keeper, Sir Nathan Wright,[713] and to have settled it officially on the Great Seal. It was once the residence of Sir John Somers, the Lord Chancellor.

In 1739 Lady Henrietta Herbert, widow of Lord William[Pg 411] Herbert, second son of the Marquis of Powis, and daughter of James, first Earl of Waldegrave, was married to Mr. John Beard,[714] who seems to have been a fine singer and a most charitable, estimable man. Lady Henrietta’s grandmother was the daughter of James II. by the sister of the great Duke of Marlborough. Dr. Burner speaks of Beard’s great knowledge of music and of his intelligence as an actor.[715] In an epitaph on him, still extant, the writer says—

“Whence had that voice such magic to control?

’Twas but the echo of a well-tuned soul;

Through life his morals and his music ran

In symphony, and spoke the virtuous man.

... Go, gentle harmonist! our hopes approve,

To meet and hear thy sacred songs above;

When taught by thee, the stage of life well trod,

We rise to raptures round the throne of God.”

Beard, excellent both in oratorios and serious and comic operas, became part proprietor of Covent Garden Theatre, and died in 1791.

The Duke of Newcastle’s crowded levées were his pleasure and his triumph. He generally made people of business wait two or three hours in the ante-chamber while he trifled with insignificant favourites in his closet. When at last he entered the levée room, he accosted, hugged, embraced, and promised everything to everybody with an assumed cordiality and a degrading familiarity.[716]

“Long” Sir Thomas Robertson was a great intruder on the duke’s time; if told that he was out, he would come in to look at the clock or play with the monkey, in hopes of the great man relenting. The servants, at last tired out with Sir Thomas, concocted a formula of repulses, and the next time he came the porter, without waiting for his question, began—“Sir, his grace is gone out, the fire has gone out, the clock stands, and the monkey is dead.”[717]

[Pg 412]Sir Timothy Waldo, on his way from the duke’s dinner-table to his own carriage, once gave the cook, who was waiting in the hall, a crown. The rogue returned it, saying he did not take silver. “Oh, don’t you, indeed?” said Sir Timothy, coolly replacing it in his pocket; “then I don’t give gold.” Jonas Hanway, the great opponent of tea-drinking, published eight letters to the duke on this subject,[718] and the custom began from that time to decline. But Hogarth had already condemned the exaction.

The duke was very profuse in his promises, and a good story is told of the result of his insincerity. At a Cornish election, the duke had obtained the turning vote for his candidate by his usual assurances. The elector, wishing to secure something definite, had asked for a supervisorship of excise for his son-in-law on the present holder’s death. “The moment he dies,” said the premier, “set out post-haste for London; drive directly to my house in the Fields: night or day, sleeping or waking, dead or alive, thunder at the door; the porter will show you upstairs directly; and the place is yours.” A few months after the old supervisor died, and up to London rushed the Cornish elector.

Now that very night the duke had been expecting news of the death of the King of Spain, and had left orders before he went to bed to have the courier sent up directly he arrived. The Cornish man, mistaken for this important messenger, was instantly, to his great delight, shown up to the duke’s bedroom. “Is he dead?—is he dead?” cried the duke. “Yes, my lord, yes,” answered the aspirant, promptly. “When did he die?” “The day before yesterday, at half-past one o’clock, after three weeks in his bed, and taking a power of doctor’s stuff; and I hope your grace will be as good as your word, and let my son-in-law succeed him.” “Succeed him!” shouted the duke; “is the man drunk or mad? Where are your despatches?” he exclaimed, tearing back the bed-curtains; and there, to his vexation, stood the blundering elector, hat in hand, his stupid red face beaming with smiles as he kept bowing like a joss.[Pg 413] The duke sank back in a violent fit of laughter, which, like the electric fluid, was in a moment communicated to his attendants.[719] It is not stated whether the Cornish man obtained his petition.

There is an agreement in all the stories of the duke, who was thirty years Secretary of State, and nearly ten years First Lord of the Treasury, “whether told,” says Macaulay, “by people who were perpetually seeing him in Parliament and attending his levées in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, or by Grub Street writers, who had never more than a glimpse of his star through the windows of his gilded coach.”[720] Smollett and Walpole mixed in different society, yet they both sketch the duke with the same colours. Smollett’s Newcastle runs out of his dressing-room with his face covered with soapsuds to embrace the Moorish envoy. Walpole’s Newcastle pushes his way into the Duke of Grafton’s sick-room to kiss the old nobleman’s plaisters. “He was a living, moving, talking caricature. His gait was a shuffling trot, his utterance a rapid stutter. He was always in a hurry—he was never in time; he abounded in fulsome caresses and in hysterical tears. His oratory resembled that of Justice Shallow—it was nonsense effervescent with animal spirits and impertinence. ‘Oh yes, yes, to be sure—Annapolis must be defended; troops must be sent to Annapolis. Pray, where is Annapolis?’—‘Cape Breton an island! Wonderful! Show it me on the map. So it is, sure enough. My dear sir, you always bring us good news. I must go and tell the king that Cape Breton is an island.’ His success is a proof of what may be done by a man who devotes his whole heart and soul to one object. His love of power was so intense a passion, that it almost supplied the place of talent. He was jealous even of his own brother. Under the guise of levity, he was false beyond all example.” “All the able men of his time ridiculed him as a dunce, a driveller, a child, who never knew his own mind for an hour together, and yet he overreached them all round.” If the country had remained at peace, this man[Pg 414] might have been at the head of affairs till a new king came with fresh favourites and a strong will; “but the inauspicious commencement of the Seven Years’ War brought on a crisis to which Newcastle was altogether unequal. After a calm of fifteen years, the spirit of the nation was again stirred to its inmost depths.”

This is strongly etched, but Macaulay was too fond of caricature for a real lover of truth. Walpole, recounting this greedy imbecile’s disgrace, reviews his career much more forcibly, for in a few words he shows us how great had been the power which this chatterer’s fixed purpose had attained. The memoir-writer describes the duke as the man “who had begun the world by heading mobs against the ministers of Queen Anne; who had braved the heir-apparent, afterwards George I., and forced himself upon him as godfather to his son; who had recovered that prince’s favour, and preserved power under him, at the expense of every minister whom that prince preferred; who had been a rival of another Prince of Wales for the chancellorship of Cambridge; and who was now buffeted from a fourth court by a very suitable competitor (Lord Bute), and reduced in his tottery old age to have recourse to those mobs and that popularity which had raised him fifty years before.”

Lord Bute was mean enough to compliment the old duke on his retirement. The duke replied, with a spirit that showed the vitality of his ambition: “Yes, yes, my lord, I am an old man, but yesterday was my birthday, and I recollected that Cardinal Fleury began to be prime-minister of France just at my age.”[721]

Newcastle House, now occupied by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, was, for forty years or more, inhabited by Sir Alan Chambre, one of King George III.’s judges. The society, then lodged in Bartlett’s Buildings, in Holborn, derived its first name from that place, and at Sir Alan’s death they purchased the house and site.

About the centre of the west side of the square, in Sir Alan’s time, lived the Earl and Countess of Portsmouth.[Pg 415] The earl was half-witted, but was always well-conducted and quite producible in society under the guidance of his countess, a daughter of Lord Grantley.

Near Surgeons’ Hall, at the same epoch, lived the first Lord Wynford, Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, better known as Serjeant Best. A quarrel between this irritable lawyer and Serjeant Wilde, afterwards Lord Chancellor Truro, one of the most stalwart gladiators who ever won a name and title in the legal arena, gave rise to an epigram, the point of which was—“That Best was wild, and Wilde was best.”

In 1774, when Lord Clive had rewarded Wedderburn, his defender, with lacs of rupees and a villa at Mitcham, the lawyer had an elegant house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, not far from the Duke of Newcastle’s,—“a quarter,” says Lord Campbell, “which I recollect still the envied resort of legal magnates.”

Wedderburn, afterwards better known as Lord Chancellor Loughborough, had a special hatred for Franklin, and loaded him with abuse before a committee of the Privy Council, for having sent to America letters from the Lieutenant-Governor of Massachusetts, urging the Government to employ military force to suppress the discontents in New England.[722] The effect of Wedderburn’s brilliant oratory in Parliament was ruined, says Lord Campbell, by “his character for insincerity.”[723] When George III. heard of his death, he is reported to have said, “He has not left a greater knave behind him in my dominions;” upon which Lord Thurlow savagely said, with his usual oath, “I perceive that his majesty is quite sane at present.” Wedderburn was a friend of David Hume; his humanity was eulogised by Dr. Parr, but he was satirised by Churchill in the Rosciad.

Montague, Earl of Sandwich, the great patron of Pepys, lived in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, paying £250 a year rent.[724] Pepys calls it “a fine house, but deadly dear.”[725] He visits[Pg 416] him, February 10, 1663-4, and finds my lord very high and strange and stately, although Pepys had been bound for £1000 with him, and the shrewd cit naturally enough did not like my lord being angry with him and in debt to him at the same time. The earl was a distant cousin of Pepys, and on his marriage received him and his wife into his house, and took Pepys with him when he went to bring home Charles II., when he was elected one of the Council of State and General at Sea. He brought the queen-mother to England and took her back again. He also brought the ill-fated queen from Portugal, and became a privy-councillor, and was sent as ambassador to Spain. He seems to have been not untainted with the vices of the age. He was in the great battle where Van Tromp was killed, and in 1668 he took forty-five sail from the Dutch at sea, and that is the best thing known of him. He died in 1672, and was buried in great state.

Inigo Jones built only the west side of the square. No. 55 was the residence of Robert Bertie, Earl of Lindsey, a general of King Charles. It is described in 1708 as a handsome building of the Ionic order, with a beautiful and strong Court Gate, formed of six spacious brick piers, with curious ironwork between them, and on the piers large and beautiful vases.[726] The open balustrade at the top bore six urns.

The Earl of Lindsey was shot at Edgehill in 1642, when a reckless and intemperate charge of Rupert had led to the total defeat of the unsupported foot. His son, Lord Willoughby, was taken in endeavouring to rescue his father. Clarendon describes the earl as a lavish, generous, yet punctilious man, of great honour and experience in foreign war. He was surrounded by Lincolnshire gentlemen, who served in his regiment out of personal regard for him. He was jealous of Prince Rupert’s interference, and had made up his mind to die. As he lay bleeding to death he reproved the officers of the Earl of Essex, many of them his old friends, for their ingratitude and “foul rebellion.”[727]

[Pg 417]The fourth Earl of Lindsey was created Duke of Ancaster, and the house henceforward bore that now forgotten name. It was subsequently sold to the proud Duke of Somerset, the same who married the widow of the Mr. Thynne whom Count Königsmarck murdered.

In the early part of George III.’s reign Lindsey House became a sort of lodging-house for foreign members of the Moravian persuasion. The staircase, about 1772, was painted with scenes from the history of the Herrnhuthers. The most conspicuous figures were those of a negro catechumen in a white shirt, and a missionary who went over to Algiers to preach to the galley-slaves, and died in Africa of the plague. There was also a painting of a Moravian clergyman being saved from a desert rock on which he had been cast.[728]

Repeated mention of the Berties is made in Horace Walpole’s pleasant Letters. Lord Robert Bertie was third son of Robert the first Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven. He was a general in the army, a colonel in the Guards, and a lord of the bedchamber. He married Lady Raymond in 1762, and died in 1782.

The proud Duke of Somerset, in 1748, left to his eldest daughter, Lady Frances, married to the Marquis of Granby, three thousand a year, and the fine house built by Inigo Jones in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which he had bought of the Duke of Ancaster for the Duchess, hoping that his daughter would let her mother live with her.[729] In July 1779 the Duke of Ancaster, dying of drinking and rioting at two-and-twenty, recalls much scandal to Walpole’s mind. He had been in love with Lady Honoria, Walpole’s niece; but Horace does not regret the match dropping through, for he says the duke was of a turbulent nature, and, though of a fine figure, not noble in manners. Lady Priscilla Elizabeth Bertie, eldest sister of the duke, married the grandson of Peter Burrell, a merchant, who became husband of the Lady Great Chamberlain of England, and inherited a barony and[Pg 418] half the Ancaster estate.[730] “The three last duchesses,” goes on the cruel gossip, “were never sober.” “The present duchess-dowager,” he adds, “was natural daughter of Panton, a disreputable horse-jockey of Newmarket. The other duchess was some lady’s woman, or young lady’s governess.” Mr. Burrell’s daughters married Lord Percy and the Duke of Hamilton.

In 1791 Walpole writes to Miss Berry to describe the marriage of Lord Cholmondeley with Lady Georgiana Charlotte Bertie: “The men were in frocks and white waistcoats. The endowing purse, I believe, has been left off ever since broad pieces were called in and melted down. We were but eighteen persons in all.... The poor duchess-mother wept excessively; she is now left quite alone,—her two daughters married, and her other children dead. She herself, I fear, is in a very dangerous way. She goes directly to Spa, where the new married pair are to meet her. We all separated in an hour and a half.”[731]

Alfred Tennyson in early life had fourth-floor chambers at No. 55, and there probably his friend Hallam, whose early death he laments in his In Memoriam spent many an hour with him. There, in the airy regions of Attica, in a low-roofed room, the single window of which is darkened by a huge stone balustrade—a gloomy relic of past grandeur—the young poet may have recited the majestic lines of his “King Arthur,” or the exquisite lament of “Mariana,” and there he may have immortalised the “plump head-waiter of the Cock,” in Fleet Street. Mr. John Foster, the author of many sound and delightful historical biographies, had also chambers in this house.

No. 68, on the west side, stands on the site of the approach to the stables of old Newcastle House. Here Judge Le Blanc lived, and at his death the house was occupied by Mr. Thomas Le Blanc, Master of Trinity Hall, Cambridge.

At No. 33, on the same side as the Insolvent Debtors’ Court, dwelt Judge Park, a man much beloved by his friends;[Pg 419] in his early days, as a young and poor Scotch barrister, he had lived in Carey Street till his house there was burnt down. He used to say that his great ambition in youth had been to one day live at No. 33 in the Fields, at that time occupied by Chief Justice Willis; but in later days, as a judge, leaving the former goal of his ambition, he migrated to Bedford Square, where he died.

Nos. 40 and 42, on the south side, form the Museum of the College of Surgeons, incorporated in 1800. The Grecian front is a most clever contrivance by Sir John Soane. The building contains the incomparable anatomical collection of the eminent John Hunter, bought by the Government for £15,000 and given to the College of Surgeons on condition of its being opened to the public. John Hunter died in 1793; and the first courses of lectures in the new building were delivered by Sir Everard Home and Sir William Blizard, in 1810. The Museum was built by Barry in 1835, and cost about £40,000.[732] It is divided into two rooms, the normal and abnormal. The total number of specimens is upwards of 23,000. The collection is unequalled in many respects; every article is authentic and in perfect preservation. The largest human skeleton is that of Charles O’Brien, the Irish giant, who died in Cockspur Street, Charing Cross, in 1783, aged twenty-two. It measures eight feet four inches. By its side, in ghastly contrast, is the bony sketch of Caroline Crachami, a Sicilian dwarf who died in 1824, aged ten years. There is also a cast of the hand of Patrick Cotter, another Irish giant, who measured eight feet seven and a half inches. Nor must we overlook the vast framework of Chunee, the elephant that went mad with toothache at Exeter Change, and was shot by a company of riflemen in 1826. The sawn base of the inflamed tusk shows a spicula of ivory pressing into the nervous pulp. Toothache is always terrible, but only imagine a square foot of it!

Very curious too, are the jaw of the extinct sabre-toothed tiger, and the skeleton of a gigantic extinct Irish deer found[Pg 420] under a bed of shell-marl in a peat bog near Limerick. The antlers are seven feet long, eight feet across, and weigh seventy-six pounds. The height of the animal (measured from his skull) was seven feet six inches. Amongst other horrors, there is a cast of the fleshy band that united the Siamese twins, and one of a woman with a long curved horn growing from her forehead. There are also many skulls of soldiers perforated and torn with bullets, the lead still adhering to some of the bony plates of the crania. But the wonder of wonders is the iron pivot of a trysail-mast that was driven clean through the chest of a Scarborough lad. The boy recovered in five months, and not long after went to work again. It is a tough race that rules the sea.

There are also fragments of the skeleton of a rhinoceros discovered in a limestone cavern at Oreston during the formation of the Plymouth Breakwater. In a recess from the gallery stands the embalmed body of the wife of Martin Van Butchell, an impudent Dutch quack doctor. It is coarsely preserved, and is very loathsome to look at. It was prepared in 1775 by Dr. W. Hunter and Mr. Cruikshank, the vascular system being injected with oil of turpentine and camphorated spirits of wine, and powdered nitre and camphor being introduced into the cavities. On the case containing the body is an advertisement cut from an old newspaper, stating the conditions which Dr. Van Butchell required of those who came to see the body of his wife. At the feet of Mrs. Van Butchell is the shrunken mummy of her pet parrot.

The pictures include the portrait of John Hunter by Reynolds, which Sharp engraved: it has much faded. There is also a posthumous bust of Hunter by Flaxman, and one of Clive by Chantrey. Any Fellow of the College can introduce a visitor, either personally or by written order, the first four days of the week. In September the Museum is closed. It would be much more convenient for students if some small sum were charged for admission. It is now visited but by two or three people a day, when it should be inspected by hundreds.

[Pg 421]That great surgeon, John Hunter, was the son of a small farmer in Lanarkshire. He was born in 1728, and died in 1793. In early life he went abroad as an army-surgeon to study gunshot-wounds; and in 1786 he was appointed deputy surgeon-general to the army. In 1772 he made discoveries as to the property of the gastric juice. He was the first to use cutting as a cure for hydrophobia, and to distinguish the various species of cancer. He kept at his house at Brompton a variety of wild animals for the purposes of comparative anatomy, was often in danger from their violence, and as often saved by his own intrepidity. Sir Joseph Banks divided his collection between Hunter and the British Museum. Unequalled in the dissecting-room, Hunter was a bad lecturer. He was an irritable man, and died suddenly during a disputation at St. George’s Hospital which vexed him. His death is said to have been hastened by fear of death from hydrophobia, he having cut his hand while dissecting a man who had died of that mysterious disease. Hunter used to call an operation “opprobrium medici.”

In Portugal Row, as the southern side of the square used to be called, lived Sir Richard Fanshawe, the translator of the Lusiad of Camoens, and of Guarini’s Pastor Fido. Sir Richard was our ambassador in Spain; but Charles, wishing to get rid of Lord Sandwich from the navy, recalled Fanshawe, on the plea that he had ventured to sign a treaty without authority. He died in 1666, on the intended day of his return, of a violent fever, probably caused by vexation at his unmerited disgrace. Sir Richard appears to have been a religious, faithful man and a good scholar, but born in unhappy times and to an ill fate. Charles I. had very justly a great respect for him. His wife was a brave, determined woman, full of affection, good sense, and equally full of hatred and contempt for Lord Sandwich, Pepys’s friend, who had supplanted her husband in the embassy.

On one occasion, on their way to Malaga, the Dutch trading vessel in which she and her husband were was threatened by a Turkish galley which bore down on them in full sail.[Pg 422] The captain, who had rendered his sixty guns useless by lumbering them up with cargo, resolved to fight for his £30,000 worth of goods, and therefore armed his two hundred men and plied them with brandy. The decks were partially cleared, and the women ordered below for fear the Turks might think the vessel a merchant-ship and board it. Sir Richard, taking his gun, bandolier, and sword, stood with the ship’s company waiting for the Turks.[733] But we must quote the brave wife’s own simple words:—“The beast the captain had locked me up in the cabin. I knocked and called long to no purpose, until at length the cabin-boy came and opened the door. I, all in tears, desired him to be so good as to give me the blue thrum cap he wore and his tarred coat, which he did, and I gave him half-a-crown; and putting them on, and flinging away my night-clothes, I crept up softly and stood upon the deck by my husband’s side, as free from fear as, I confess, from discretion; but it was the effect of that passion which I could never master. By this time the two vessels were engaged in parley, and so well satisfied with speech and sight of each other’s forces, that the Turks’ man-of-war tacked about and we continued our course. But when your father saw me retreat, looking upon me, he blessed himself and snatched me up in his arms, saying, ‘Good God! that love can make this change!’ and though he seemingly chid me, he would laugh at it as often as he remembered that journey.” This same vessel, a short time after, was blown up in the harbour with the loss of more than a hundred men and all the lading.[734]

This brave, good woman showed still greater fortitude when her husband died and left her almost penniless in a strange country. She had only twenty-eight doubloons with which to bring home her children, and sixty servants, and the dead body of her husband. She, however, instantly sold her carriages and a thousand pounds’ worth of plate, and setting apart the queen’s present of two thousand doubloons for travelling expenses, started for England. “God,” she[Pg 423] says, in her brave, pious way, “did hear, and see, and help me, and brought my soul out of trouble.”

In 1677 Lady Fanshawe took a house in Holborn Row, the north side of the square, and spent a year lamenting “the dear remembrances of her past happiness and fortune; and though she had great graces and favours from the king and queen and whole court, yet she found at the present no remedy.”[735]

Lord Kenyon lived at No. 35 in 1805. Jekyll was fond of joking about Kenyon’s stinginess, and used to say he died of eating apple-pie crust at breakfast to save the expense of muffins; and that Lord Ellenborough, who succeeded on Kenyon’s death to the Chief Justiceship, always used to bow to apple-pie ever afterwards which Jekyll called his “apple-pie-ety.” The princesses Augusta and Sophia once told Tom Moore, at Lady Donegall’s that the king used to play tricks on Kenyon and send the despatch-box to him at a quarter past seven, when it was known the learned lord was in bed to save candlelight.[736] Lord Ellenborough used to say that the final word in “Mors janua vitæ” was mis-spelled vita on Kenyon’s tomb to save the extra cost of the diphthong.[737] George III. used to say to Kenyon, “My Lord, let us have a little more of your good law, and less of your bad Latin.”

Lord Campbell, who gives a very pleasant sketch of Chief Justice Kenyon, with his bad temper and bad Latin, his hatred of newspaper writers and gamblers, and his wrath against pettifoggers, describes his being taken in by Horne Tooke, and laughs at his ignorantly-mixed metaphors. He seems to have been a respectable second-rate lawyer, conscientious and upright. “He occupied,” says Lord Campbell, “a large gloomy house, in which I have seen merry doings when it was afterwards transferred to the Verulam Club.” The tradition of this house was that “it was always Lent in the kitchen and Passion Week in the parlour.” On some one mentioning the spits in Lord Kenyon’s kitchen, Jekyll said, “It is irrelevant to talk about the spits, for[Pg 424] nothing turns upon them.” The judge’s ignorance was profound. It is reported that in a trial for blasphemy the Chief Justice, after citing the names of several remarkable early Christians, said, “Above all, gentlemen, need I name to you the Emperor Julian, who was so celebrated for the practice of every Christian virtue that he was called Julian the Apostle?”[738] On another occasion, talking of a false witness, he is supposed to have said, “The allegation is as far from truth as ‘old Boterium from the northern main’—a line I have heard or met with, God knows where.”[739]

Lord Erskine lived at No. 36, in 1805, the year before he rose at once to the peerage and the woolsack, and presided at Lord Melville’s trial. He did not hold the seals many months, and died in 1823. This great Whig orator was the youngest son of the Earl of Buchan. He was a midshipman and an ensign before he became a student at Lincoln’s Inn. He began to be known in 1778; in 1781 he defended Lord George Gordon, in 1794 Horne Tooke, Hardy, Thelwall, and afterwards Tom Paine.

The house that contains the Soane Museum, No. 13 on the north side, was built in 1812, and, consisting of twenty-four small apartments crammed with curiosities, is in itself a marvel of fantastic ingenuity. Every inch of space is turned to account. On one side of the picture-room are cabinets, and on the other movable shutters or screens, on which pictures are also hung; so that a small area, only thirteen feet long and twelve broad, contains as much as a gallery forty-five feet long and twenty feet broad. A Roman altar once stood in the outer court.

It is a disgrace to the trustees that this curious museum is kept so private, and that such impediments are thrown in the way of visitors. It is open only two days a week in April, May, and June, but at certain seasons a third day is granted to foreigners, artists, and people from the country. To obtain tickets, you are obliged to get, some days before you visit, a letter from a trustee, or to write to the curator, enter your name in a book, and leave your card. All this[Pg 425] vexatious hindrance and fuss has the desired effect of preventing many persons from visiting a museum left, not to the trustees or the curator, but to the nation—to every Englishman. In order to read the books, copy the pictures, or examine the plans and drawings, the same tedious and humiliating form must be gone through.

The gem of all the Soane treasures is an enormous transparent alabaster sarcophagus, discovered by Belzoni in 1816 in a tomb in the valley of Beban el Molook, near Thebes. It is nine feet four inches long, three feet eight inches wide, two feet eight inches deep, and is covered without and within with beautifully-cut hieroglyphics. It was the greatest discovery of the runaway Paduan Monk, and was undoubtedly the cenotaph or sarcophagus of a Pharaoh or Ptolemy. It was discovered in an enormous tomb of endless chambers, which the Arabs still call “Belzoni’s tomb.” On the bottom of the case is a full-length figure in relief, of Isis, the guardian of the dead. Sir John Soane gave £2000 for this sarcophagus to Mr. Salt, Consul General of Egypt and Belzoni’s employer. The raised lid is broken into nineteen pieces. The late Sir Gardner Wilkinson considered this to be the cenotaph of Osirei, the father of Rameses the Great. But the forgotten king for whom the Soane sarcophagus was really executed was Seti, surnamed Meni-en-Ptah, the father of Rameses the Great; he is called by Manetho Séthos.[740] Dr. Lepsius dates the commencement of his reign B.C. 1439. Dr. Brugsch places it twenty years earlier. Mr. Sharpe, with that delightful uncertainty characteristic of Egyptian antiquaries, drags the epoch down two hundred years later. Seti was the father of the Pharaoh who persecuted the Israelites, and he made war against Syria. His son was the famous Rameses. All three kings were descended from the Shepherd Chiefs. The most beautiful fragment in Karnak represents this monarch, Seti, in his chariot, with a sword like a fish-slice in one hand, while in the other he clutches[Pg 426] the topknots of a group of conquered enemies, Nubian, Syrian, and Jewish. The work is full of an almost Raphaelesque grace.

After this come some of Flaxman’s and Banks’s sketches and models, a cast of the shield of Achilles by the former, and one of the Boothby monument by the latter. There is also a fine collection of ancient gems and intaglios, pure in taste and exquisitely cut, and a set of the Napoleon medals, selected by Denon for the Empress Josephine, and in the finest possible state. We may also mention Sir Christopher Wren’s watch, some ivory chairs, and a table from Tippoo Saib’s devastated palace at Seringapatam, and a richly-mounted pistol taken by Peter the Great from a Turkish general at Azof in 1696. The latter was given to Napoleon by the Russian emperor at the treaty of Tilsit in 1807, and was presented by him to a French officer at St. Helena. The books, too, are of great interest. Here is the original MS. copy of the Gierusalemme Liberata, published at Ferrara in 1581, and in Tasso’s own handwriting; the first four folio editions of Shakspere, once the property of that great actor and Shaksperean student John Philip Kemble; a folio of designs for Elizabethan and Jacobean houses by the celebrated architect John Thorpe; Fauntleroy the forger’s illustrated copy of Pennant’s London, purchased for six hundred and fifty guineas; a Commentary on Paul’s Epistles, illuminated by the laborious Croatian, Giulio Clovio (who died in 1578), for Cardinal Grimani. Vasari raves about the minute finish of this painter.

The pictures, too, are good. There are three Canalettis full of that Dutch Venetian’s clear common sense; the finest, a view on the Grand Canal—his favourite subject—and “The Snake in the Grass,” better known as “Love unloosing the Zone of Beauty,” by Reynolds. There is a sadly faded replica of this in the Winter Palace at St. Petersburg. This one was purchased at the Marchioness of Thomond’s sale for £500. The “Rake’s Progress,” by Hogarth, in eight pictures, was purchased by Sir John in 1802 for £598. These inimitable pictures are incomparable, and display the[Pg 427] fine, pure, sober colour of the great artist, and his broad touch so like that of Jan Steen.