Haunted London, Index

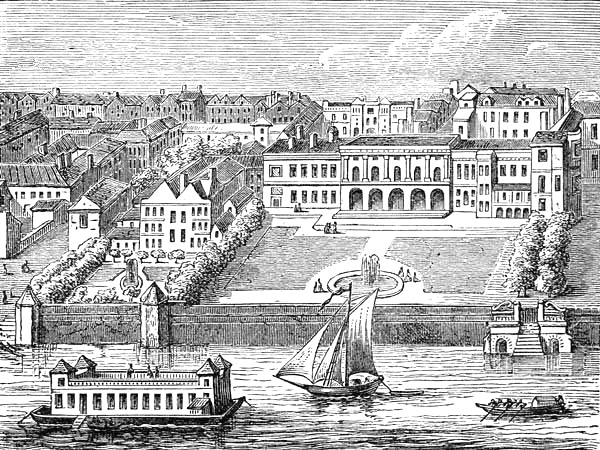

SOMERSET HOUSE FROM THE RIVER, 1746.

CHAPTER IV.

SOMERSET HOUSE.

| “And every day there passes by my side, Up to its western reach, the London tide— The spring tides of the term. My front looks down On all the pride and business of the town; My other fair and more majestic face For ever gazes on itself below, In the best mirror that the world can show.” Cowley. |

That ambitious and rapacious noble the Protector Somerset, brother of Queen Jane Seymour, and maternal uncle of Edward VI., the owner of more than two hundred manors,[96] and who boasted that his own friends and retainers made[Pg 57] up an army of ten thousand men, determined to build a palace in the Strand. For this purpose he demolished the parish church of St. Mary, and pulled down the houses of the Bishops of Worcester, Llandaff, and Lichfield. He also began to remove St. Margaret’s, at Westminster, for building materials, till his masons were driven away by rioters. He destroyed a chapel in St. Paul’s Churchyard, with a cloister containing the “Dance of Death,” and a charnel-house, the bones of which he buried in unconsecrated ground,[97] and finally stole the stones of the church of St. John of Jerusalem, near Smithfield,[98] and those of Strand Inn (belonging to the Temple), where Occleve the poet, a contemporary of Gower and Chaucer, had studied law.

The unwise Protector determined in this building to rival Whitehall and Hampton Court. It was begun probably about 1549, and no doubt remained unfinished at his death. He had at that time lavished on it £50,000 of our present money.

The architect was John of Padua,[99] Henry VIII.’s architect, who built Longleat, in Wiltshire, the seat of the Marquis of Bath, a magnificent specimen of the Italian-Elizabethan style, and also the gates of Caius College, at Cambridge. The Protector is said to have spent at one time £100 a day in building, every stone he laid bringing him nearer to his own narrow home. A plan of the house is still preserved in the Soane Museum.[100]

After the attainder of the duke, when the new palace became the property of the crown, little was done to complete the building. The screen prepared for the hall was bought for St. Bride’s, where it was probably destroyed in the Great Fire.[101] The Protector was a good friend to the people, but he was weak and ambitious, and the plotters of Ely House had no difficulty in dragging him to the scaffold. The minority of Edward brought many of the Strand noblemen to the axe, but the fate of the admiral and his brother did not deter their neighbours Northumberland, Raleigh, Norfolk, and Essex.

[Pg 58]Elizabeth granted the keeping of Somerset House to her faithful cousin Lord Hunsdon, for life,[102] and here she frequently would visit him, in a jewelled farthingale, with Raleigh and Essex in her train.

In 1616 that Scotch Solomon, James I., commanded the place to be called Denmark House; and his queen kept her gay and not very decent court here, so that Ben Jonson must have often seen his glorious masques acted in this palace, to which his coadjutor Inigo Jones built a chapel, and made other additions. Anne of Denmark and her maids-of-honour kept up here a continual masquerade,[103] appearing in various dresses, and transforming themselves to the delight of all whose interest it was to be delighted.

Here too that impetuous queen, Henrietta Maria, resided with her wilful and extravagant French household, whose insolence irritated and disgusted the people and offended Charles the First. The king at last, losing patience, summoned them together one evening and dismissed them all. They behaved like sutlers at the sack of a town. They claimed fictitious debts; they invented exorbitant bills; they greedily divided among each other the queen’s wardrobe and jewels, scarcely leaving her a change of linen. The king paid nearly £50,000 to get rid of them; Madame St. George alone claiming several thousand pounds besides jewels.[104] They still delayed their departure; on which the king, at last roused, wrote the following imperative letter to Buckingham:—

“Steenie—I have received your letter by Dick Greame. This is my answer. I command you to send all the French away to-morrow out of the town, if you can by fair means (but stick not long in disputing), otherways force them away—driving them away like so many wild beasts until ye have shipped them; and the devil go with them. Let me hear no answer, but of the performance of my command. So I rest

“Your faithful, constant, loving friend,

“C. R.

“Oaking, the seventh of August, 1626.”

[Pg 59]As the French invented all sorts of vexatious delays, the yeomen of the guard at last jostled them out, carting them off in nearly forty coaches. They arrived at Dover after four days’ tedious travelling, wrangling, and bewailing. The squib did not burn out without one final detonation. As the vivacious Madame St. George stepped into the boat, with perhaps some insolent gesture of adieu, a man in the mob flung a stone at her French cap. A gallant Englishman who was escorting her instantly quitted his charge, ran the fellow through the body, and returned to the boat. The man died on the spot, but no notice, it appears, was taken of the murderer.

In Somerset House, at the Christmas masque of 1632-3, Charles’s high-spirited queen took part for the last time in a masque. Unfortunately for Prynne, the next day out came his Histriomastix, with a scurrilous marginal note, “Women actors notorious whores!” for which the stubborn fanatic lost his ears.

Queen Henrietta had, in Somerset House, an ostentatiously magnificent Catholic chapel built by Inigo Jones, which became the scene of spectacles that were gall and wormwood to the Puritans, who were already couching for their spring.

Their time came in March 1643, when Roundheads, grimly rejoicing, burnt all the pictures, images, Jesuitical books, and tapestry.[105]

Five of the unhappy queen’s French Roman Catholic servants are entombed in the cellars of the present building, under the great quiet square.[106]

Here, close to his own handiwork, that distinguished architect, Inigo Jones, who had lodgings in the palace, died in 1652.

About the same time the House of Peers permitted the Protestant service to be held in Somerset House instead of in Durham House. This drove out the Quakers and Anabaptists, and prevented the pulling down of the palace and[Pg 60] the making of a street from the garden through the chapel and back-yard up into the Strand.[107]

The Protector’s palace was the scene of a great and sad event in November 1658; for the body of Cromwell, who had died at Whitehall, lay in state here for several days. He lay in effigy on a bed of royal crimson velvet, covered with a velvet gown, a sceptre in his hand, and a crown upon his head. The Cavaliers, whose spirits were recovering, were very angry at this foolish display,[108] forgetting that it was not poor Oliver’s own doing; and the baser people, who follow any impulse of the day, threw dirt in the night upon the blazoned escutcheon that was displayed over the great gate of Somerset House.

The year after, an Act was passed to sell all royal property, and Somerset House was disposed of for £10,000. The Restoration soon stepped in and annulled the bargain. After the return of the son who so completely revenged upon us the death of his father, the luckless palace became the residence of its former inhabitant, now older and gentler—the queen-mother. She improved and beautified it. The old courtier, Waller, only fifty-seven at the time, wrote some fulsome verses on the occasion. He talks of her adorning the town as with a brave revenge, to show—

“That glory came and went with you.”

He mentions also the view from the palace:—

“The fair view her window yields,

The town, the river, and the fields.”

Cowley, the son of a Fleet Street grocer, flew still higher, larded his flattery with perverted texts, like a Puritanised Cavalier time-server, and wrote—

“On either side dwells Safety and Delight;

Wealth on the left and Power sits on the right.”

In May 1665, when the queen-mother, who had lived in Somerset House with her supposed husband, the Earl of St. Albans, took her farewell of England for a gayer court,[Pg 61] Cowley wrote these verses to the setting sun, in hopes to propitiate the rising sun; for here, too, lived Catherine of Braganza, the unhappy wife of Charles II.

There were strange scenes at Somerset House even during the queen-mother’s residence, for the old court gossip Pepys describes being taken one day to the Presence-chamber.[109] He found the queen not very charming, but still modest and engaging. Lady Castlemaine was there, Mr. Crofts, a pretty young spark of fifteen (her illegitimate child), and many great ladies. By and by in came the king and the Duke and Duchess of York. The conversation was not a very decorous one; and the young queen said to Charles, “You lie!” which made good sport, as the chuckling and delighted Pepys remarks, those being the first English words he had heard her say; and the king then tried to make her reply, “Confess and be hanged.”

In another place Pepys indignantly describes “a little proud, ugly, talkative lady crying up the queen-mother’s court as more decorous than the king’s;” yet the diary-keeper confesses that the former was the better attended, the old nobility dreading, I suppose, the scandal of Whitehall.[110]

In 1670 Monk, Duke of Albemarle, having died at his lodgings in the Cockpit, at Whitehall, lay in state in Somerset House, and was afterwards buried with almost regal pomp in Henry VII.’s Chapel.

In October 1678, the infamous devisers of the Popish plot connected Somerset House and the attendants in the Queen’s Chapel with the murder of a City magistrate, the supposed Protestant martyr, Sir Edmondbury Godfrey, who was found murdered in a field near Primrose Hill, “between Kilburn and Hampstead,” as it was then thought necessary to specify. The lying witnesses, Prance and Bedloe, swore that the justice had been inveigled into Somerset House under pretence of being wanted to keep the peace between two servants who were fighting in the yard; that he was then strangled, his neck broken, and his own sword run through his body. The corpse was kept four days, then carried in a[Pg 62] sedan-chair to Soho, and afterwards on a horse to Primrose Hill, nearly three miles off. The secrecy and convenient neighbourhood of the river for hiding a murdered man seem never to have struck the rogues, who forgot even to “lie like truth,” so credulous and excited was the multitude.

Waller, says Aubrey, though usually very temperate, was once made drunk at Somerset House by some courtiers, and had a cruel fall when taking boat at the water stairs, “’Twas a pity to use such a sweet man so inhumanly.”[111] Saville used to say that “nobody should keep him company without drinking but Mr. Waller.”

In 1692 that poor ill-used woman and unhappy wife, Catherine of Braganza, left Somerset House, and returned thence to Portugal, the home of her happy childhood and happier youth.

The palace, never the home of very happy inmates, then became a lodging for foreign kings and ambassadors, and a home for a few noblemen and poor retainers of the court, much as Hampton Court is now. Lewis de Duras, Earl of Feversham, the incompetent commander at Sedgemoor, who lies buried at the Savoy, lived here in 1708; and so did Lady Arlington, the widow of Secretary Bennet, that butt of Killigrew and Rochester. In the reign of George III., Charlotte Lennox, the authoress of the Female Quixote, had apartments in Somerset House.

Houses, like men, run their allotted courses. In 1775 the old palace, which had been settled on the queen-consort in the event of her surviving the king, was exchanged for Buckingham House; and the Government instantly began to pull down the river-side palace, and erect new public offices designed by Sir William Chambers, a Scotch architect, who had given instruction in his art to George III., when Prince of Wales.

In 1630, a row of fishmongers’ stalls, in the middle of the street, over against Denmark House (Somerset House), was broken down by order of Government to prevent stalls from growing into sheds, and sheds into dwelling houses, as[Pg 63] had been the case in Old Fish Street, Saint Nicholas Shambles, and other places.[112]

On the 2d of February, 1659-60, Pepys tells us in his diary, that having £60 with him of his lord’s money, on his way from London Bridge, and hearing the noise of guns, he landed at Somerset House, and found the Strand full of soldiers. Going upstairs to a window, Pepys looked out and saw the foot face the horse and beat them back, all the while bawling for a free parliament and money. By and by a drum was heard to sound a march towards them, and they all got ready again, but the new comers proving of the same mind, they “made a great deal of joy to see one another.”[113] This was the beginning of Monk’s change, for the king returned in the following May. On the 18th of February two soldiers were hanged opposite Somerset House for a mutiny, of which Pepys was an eye-witness.

The prints of old Somerset House show a long line of battlemented wall facing the river, and a turreted and partially arcaded front. There is also a scarce view of the place by Hollar.[114] The river front has two porticos. The chapel is to the left, and near it are the cloisters of the Capuchins. The bowling-green seems to be to the right, between the two rows of trees. The garden is formal. The royal apartments were on the river side. The only memorial left of the outhouses of the old palace was the sign of a lion in the wall of a house in the Strand, that is mentioned in old records.[115]

Dryden describes his two friends, Eugenius and Neander, landing at Somerset Stairs, and gives us a pleasant picture of the summer evening, the water on which the moonbeams played looked like floating quicksilver, and some French people dancing merrily in the open air as the friends walk onwards to the Piazza.[116]

Of the old views of Somerset House, that of Moss is considered the best. There is also an early and curious one[Pg 64] by Knyff. A picture in Dulwich Gallery (engraved by Wilkinson) represents the river front before Inigo Jones had added a chapel for the queen of Charles I.[117]

Sir William Chambers built the present Somerset House. The old palace, when the clearance for the demolition began, presented a singular spectacle.[118] At the extremity of the royal apartments two large folding-doors joined Inigo Jones’s additions to John of Padua’s work. They opened into a long gallery on the first floor of the water garden wing, at the lower end of which was another gallery, making an angle which formed the original river front, and extended to Strand Lane. This old part had been long shut up, and was supposed to be haunted. The gallery was panelled and floored with oak. The chandelier chains still hung from the stucco ceilings. The furniture of the royal apartment was removed into lumber-rooms by the Royal Academy. There were relics of a throne and canopy; the crimson velvet curtains for the audience-chamber had faded to olive colour; and the fringe and lace were there, but a few threads and spangles had been peeled off them. There were also scattered about in disorder, broken chairs, stools, couches, screens, and fire-dogs.

In the older apartments much of Edward VI.’s furniture still remained. The silk hangings of the audience-chamber were in tatters, and so were the curtains, gilt-leather covers, and painted screens; one gilt chandelier also remained, and so did the sconces. A door beyond, with difficulty opened, led into a small tower on the first floor, built by Inigo Jones, and used as a breakfast-room or dressing-room by Queen Catherine. It was a beautiful octagonal domed apartment, with a tasteful cornice. The walls were frescoed, and there were pictures on the ceiling. A door from this place opened on the staircase and led to a bath-room, lined with marble, on the ground floor.

The painters of the day compared the ruined palace, characteristically enough, to the gloomy precincts of the dilapidated castles in Mrs. Radcliffe’s wax-work romances.

[Pg 65]Sir William Chambers completed his work in about five years, clearing two thousand a year. It cost more than half a million of money. The Strand front is 135 feet long; the quadrangle 210 feet wide and 296 feet deep. The main buildings are 54 feet deep and six stories high. They are faced with Portland stone, now partly sooty black, partly blanched white with the weather. The basement is adorned with rustic work, Corinthian pilasters, balustrades, statues, masks, and medallions. The river terrace was intended in anticipation of the possible embankment of the Thames. Some critics think Chambers’s great work heavy, others elegant but timid. There is too much rustic work, and the whole is rather “cut up.” The vases and niches are unmeaning, and it was a great structural fault to make the portico columns of the fine river side stand on a brittle-looking arch.

It was to Somerset House that the Royal Academy came after the split in the St. Martin’s Lane Society. Here West exhibited his respectable platitudes, Reynolds his grand portraits, and Lawrence his graceful, brilliant, but meretricious pictures. In the great room of the Academy, at the top of the building, Reynolds, Opie, Barrie, and Fuseli lectured. Through the doorway to the right of the vestibule, Reynolds, Wilkie, Turner, Flaxman, and Chantrey have often stepped. Under that bust of Michael Angelo almost all our great men from Johnson to Scott must have passed.

Carlini, an Italian friend of Cipriani, executed the two central statues on the Strand front of Somerset House, and also three of the nine colossal key-stone masks—the rivers Dee, Tyne, and Severn. Carlini was one of the unsuccessful candidates for the Beckford monument in Guildhall. When Carlini was keeper of the Academy, he used to walk from his house in Soho to Somerset Place, dressed in a deplorable greatcoat, and with a broken tobacco pipe in his mouth; but when he went to the great annual Academy dinner, he would make his way into a chair, full dressed in a purple silk coat, and scarlet gold-laced waistcoat, with point-lace[Pg 66] ruffles, and a sword and bag.[119] Wilton, the sculptor, executed the two outer figures.

Giuseppe Ceracchi, who carved some of the heads of the river gods for the key-stones of the windows of the Strand front of Somerset House, was an Italian, but it is uncertain whether he was born at Rome or in Corsica. He gave the accomplished Mrs. Damer (General Conway’s daughter) her first lessons in sculpture, an art which she afterwards perfected in the studio of the elder Bacon. Ceracchi executed the only bust in marble that Reynolds ever sat for. A statue of Mrs. Damer, from a model by him, is now in the British Museum. This sculptor was guillotined in 1801, for a plot against Napoleon.[120] He is said to have lost his wits in prison, and to have mounted the scaffold dressed as a Roman emperor. It was to Mrs. Damer (the daughter of his old friend) that Horace Walpole, our most French of memoir-writers, bequeathed his fantastic villa at Strawberry Hill, and its incongruous but valuable curiosities. She is said to have sent a bust of Nelson to the Rajah of Tanjore, who wished to spread a taste for English art in India.

The rooms round the quadrangle are hives of red-tapists. There are about nine hundred Government clerks nestled away in them, and maintained at an annual cost to us of about £275,000. There is the office of the Duchy of Cornwall, and there are the Legacy Duty, the Stamps, Taxes, and Excise Offices, the Inland Revenue Office, the Registrar General’s Office (created pursuant to 6 and 7 Will. IV., c. 86), part of the Admiralty and the Audit Office, and lastly the Will Office.

The east wing of Somerset House, used as King’s College, was built in 1829. The bronze statue of George III., and the fine recumbent figure of Father Thames, in the chief court, were cast by John Bacon, R.A.

The office for auditing the public accounts existed, under the name of the Office of the Auditors of the Imprests,[Pg 67] as far back as the time of Henry VIII. The present commission was established in 1785, and the salaries formerly paid for the passing of accounts are now paid out of the Civil List, all fees being abolished. The average annual cost of the office for auditing some three hundred and fifty accounts is £50,000. There are six commissioners, a secretary, and upwards of a hundred clerks. Almost all the home and colonial expenditure is examined at this office. Edward Harley and Arthur Maynwaring (the wit of the Kit-Cat Club) were the two Auditors of the Imprests in the reign of Queen Anne. The Earl of Oxford, the collector of MSS., obtained many curious public documents from his brother. If he had taken the whole the nation would have been a gainer; for the Government bought his collection for the British Museum, and all that he left (except what Sir William Musgrave, a commissioner, scraped together and gave to the British Museum) were barbarously destroyed by Government, heedless of their historical value. Maynwaring’s fees were about £2000 a year. The present salary of a commissioner is £1200; the chairman’s salary is £500. In 1867 the western front of Somerset House was added; it is from the designs of Pennethorne, to accommodate the clerks of the Inland Revenue Department.

The Astronomical Society, Geographical Society, and Geological Society, were for many years sheltered in Somerset House, before removing westwards.

Hither, in 1782, from Crane Court, came the Royal Society. The entrance door to the society’s rooms, to the left of the vestibule, is marked out by the bust of Sir Isaac Newton; Herschel, Davy, and Wollaston, as well as Walpole and Hallam, must have passed here, for the same door leads to the apartments of the Society of Antiquaries.

This society, when burnt out of Aldersgate Street by the Great Fire, held its meetings for a time in Arundel House. At first its doings were trifling and sometimes absurd. Enthusiasts and pedants often made the society ludicrous by their aberrations. Charles II. pretended to admire their Baconic inductions, but must have laughed at Boyle’s essays[Pg 68] and platitudes, and the hope of Wilkins, the Bishop of Chester, of flying to the moon. Evelyn’s suggestions were unpractical and dilettantish, and Pepys’s ramblings not over wise. We may be sure that there was food for laughter, when Butler could thus sketch the occupations of these philosophers:—

“To measure wind and weigh the air,

To turn a circle to a square,

And in the braying of an ass

Find out the treble and the bass,

If mares neigh alto, and a cow

In double diapason low.”

Yet how can we wonder that in the vast gold mines of the new philosophy our wise men hesitated where first to sink their shafts? Cowley chivalrously sprang forward to ward off from them the laughter and scorn of the Rochesters and the Killigrews of the day, and to prove that these initiative studies were not “impertinent and vain and small,” nothing in nature being worthless. He ends his fine, rambling ode with the following noble simile:—

“Lo! when by various turns of the celestial dance,

In many thousand years,

A star so long unknown appears,

Though Heaven itself more beauteous by it grow,

It troubles and alarms the world below;

Does to the wise a star, to fools a meteor show.”[121]

The Royal Society’s traditions belong more to Gresham College than to Somerset House, the later home of our wise men. It originated in 1645, in meetings held in Wood Street and Gresham College, suggested by Theodore Hank, a German of the Palatinate. During the Civil War its discussions were continued at Oxford. The present entrance-money is £10, and the annual subscription is £4. The society consists at present of between 700 and 800 fellows, and the anniversary is held every 30th of November, being St. Andrew’s Day. The Transactions of the society fill upwards of 150 quarto volumes. The first president[Pg 69] was Viscount Brouncker, and the second Sir Joseph Williamson. Mr. William Spottiswoode is the present president. The society possesses some valuable pictures, including three portraits of Sir Isaac Newton—one by C. Jervas, presented by the great philosopher himself, and hung over the president’s chair; a second by D. C. Marchand, and a third by Vanderbank; two portraits of Halley, by Thomas Murray and Dahl; two of Hobbes, the great advocate of despotism—one taken in 1663 (three years after the Restoration), and the other by Gaspars, presented by Aubrey; Sir Christopher Wren, by Kneller; Wallis, by West; Flamstead, by Gibson; Robert Boyle, by F. Kerseboom (a good likeness, says Boyle); Pepys, the cruel expositor of his own weaknesses, by Kneller; Sir A. Southwell, by the same portrait-painter; Dr. Birch, the great historical compiler, by Wills (the original of the mezzotint done by Faber in 1741, and bequeathed by Dr. Birch); Martin Folkes, the great antiquarian, by Hogarth; Dr. Wollaston, the eccentric discoverer, by Jackson; and Sir Humphrey Davy, by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

Amongst the curiosities of the society are the silver-gilt mace presented to the society by Charles II. in 1662—(long supposed to be the bauble which Cromwell treated with such contempt); a solar dial, made by Sir Isaac Newton himself when a boy; a reflecting telescope, made by Newton in 1671; the precious MS. of the Principia in Newton’s handwriting; a silvery lock of Newton’s hair; the MS. of the Parentalia, or Memoirs of the Family of the Wrens, written by young Wren; the charter-book of the society, bound in crimson velvet, and containing the signatures of the founder and fellows; a Rumford fireplace, one of the earliest in use; and a marble bust of Mrs. Somerville, the great mathematician and philosopher, by Chantrey. The society gives annually two gold medals—one the Rumford, the other the Copley medal, called by Sir Humphrey Davy “the ancient olive crown of the Royal Society.”

The Geological Society has a museum of specimens and fossils from all quarters of the globe. The number of its fellows is about 875, and the time of meeting alternate[Pg 70] Wednesday evenings from November till June. It also publishes a quarterly journal. The entrance-money is six guineas, the annual subscription two.

The Society of Antiquaries was fairly started in 1707, by Wanley, Bagford, and Talman, who agreed to meet together every Friday under penalty of sixpence. It had originated about 1580, when it held its first sittings in the Heralds’ College; but it did not obtain a charter till 1751, both Elizabeth and James being afraid of its meddling with royal prerogatives and illustrious genealogies, and the Civil War having interrupted its proceedings. Its first meeting was at the Bear Tavern, in the Strand. In 1739 the members were limited to one hundred, and the terms were one guinea entrance and twelve shillings annually. The society agreed to discuss antiquarian subjects, and chiefly those relating to English history prior to James I. In 1751 George II. granted its members a charter, and in 1777 George III. gave them apartments in Somerset House, where they continued till their recent removal to Burlington House. The terms now are eight guineas admission, and four guineas annually. The Archæologia, a journal of the society’s proceedings, commenced in 1770. The meetings are every Thursday evening from November to June, and the anniversary meeting is the 23d of April.

The museum of this society contains, among other treasures, the Household Book of the Duke of Norfolk; a large and valuable collection of early proclamations and ballads; T. Porter’s unique map of London (Charles I.); a folding picture in panel, of the “Preaching at Old St. Paul’s in 1616;” early portraits of Edward IV. and Richard III., engraved for the third series of Ellis’s Letters; a three-quarter portrait of Mary I. with the monogram of Lucas de Heere, and the date 1546; a curious portrait of the Marquis of Winchester (who died 1571); the portrait by Sir Antonio More, of Schorel, a Dutch painter; portraits of antiquaries—Burton, the Leicestershire antiquary, Peter le Neve, Humphrey Wanley Baker, of St. John’s College, William Stukeley, George Vertue, and Edward, Earl of[Pg 71] Oxford, presented by Vertue; a Bohemian astronomical clock of gilt brass, made in 1525 for Sigismund, King of Poland, and bought at the sale of the effects of James Ferguson, the astronomer; and a spur of gilt brass, found on Towton field, the scene of the bloody conflict between Edward IV. and the Lancastrian forces. Upon the shank is engraved the following posey—“En loial amour tout mon coer.”[122]

The Astronomical Society was instituted in 1820, and received the royal charter in 1st William IV. The entrance-money is two guineas, and the annual subscription the same amount. The annual general meeting is the second Friday in February. A medal is awarded every year. The society has a small but good mathematical library, and a few astronomical instruments.

A little above the entrance door to “the Stamps and Taxes” there is a white watch-face let into the wall. Local tradition declares it was left there in votive gratitude by a labourer who fell from a scaffolding and was saved by the ribbon of his watch catching in some ornament. It was really placed there by the Royal Society as a meridian mark for a portable transit instrument in a window of an ante-room.[123]

A tradition of Nelson belongs to this quiet square. An old clerk at Somerset House used to describe seeing the hero of the Nile pass on his way to the Admiralty. Thin and frail, with only one arm, he would enter the vestibule at a smart pace, and make direct for his goal, pushing across the rough round stones of the quadrangle, instead of taking, like others, the smooth pavement. Nelson always took the nearest way to the object he wished to attain.[124]

The Royal Academy soon found a home in Somerset House. Germs of this institution are to be found as early as the reign of Charles I., when Sir Francis Kynaston, a translator of Chaucer into Latin (circa 1636), was chosen regent of an academy in Covent Garden.[125]

[Pg 72]In 1643 that shifty adventurer, Sir Balthazar Gerbier, who had been fellow ambassador with Rubens in Spain, started some quack establishment of the same kind at Bethnal Green. He afterwards went to Surinam, was turned out by the Dutch, came back, designed an ugly house at Hampstead Marshal, in Berks, and died in 1667.

In 1711 Sir Godfrey Kneller instituted a private art academy, of which he became president. Hogarth, writing about 1760, says, that sixty years before some artists had started an academy, but their leaders assuming too much pomposity, a caricature procession was drawn on the walls of the studio, upon which the society broke up in dudgeon. Sir James Thornhill, in 1724, then set up an academy at his own house in Covent Garden, while others, under Vanderbank, turned a neighbouring meeting-house into a studio; but these rival confederations broke up at Sir James’s death in 1734.

Hogarth, his son-in-law, opened an academy, under the direction of Mr. Moser, at the house of a painter named Peter Hyde, in Greyhound Court, Arundel Street. In 1739 these artists removed to a more commodious house in Peter’s Court, St. Martin’s Lane, where they continued till 1767, when they removed to Pall Mall.

In 1738 the Duke of Richmond threw open to art-students his gallery at Whitehall, closed it again when his absence in the German war prevented the paying of the premiums, was laughed at, and then re-opened it again. It lasted some years, and Edwards, author of the Anecdotes, studied there.

In 1753 some artists meeting at the Turk’s Head, Gerrard Street, Soho, tried ineffectually to organise an academy; but in 1765 they obtained a charter, and appointed Mr. Lambert president.

In 1760 their first exhibition of pictures was held in the rooms of the Society of Arts, and in 1761 there were two exhibitions, one at Spring Gardens: for the latter Hogarth illustrated a catalogue, with a compliment to the young king and a caricature of rich connoisseurs.

[Pg 73]In 1768 eight of the directors of the Spring Gardens Society, indignant at Mr. Kirby being made president of the society in the place of Mr. Hayman, resigned; and, co-operating with sixteen others who had been ejected, secretly founded a new society. Wilton, Chambers, West, Cotes, and Moser, were the leaders in this scheme, and Reynolds soon joined them, tempted, it is supposed, by a promise of knighthood.

West was the chief mover in this intrigue. The Archbishop of York, who had tried to raise £3000 to enable the American artist to abandon portrait-painting, had gained the royal ear, and West was painting the “Departure of Regulus” for the king, who was even persuaded and flattered into drawing up several of the laws of the new society with his own hand.[126] The king, in the meantime, with unworthy dissimulation, affected outwardly a complete neutrality between the two camps, presented the Spring Gardens Society with £100, and even attended their exhibition.

The king’s patronage of the new society was disclosed to honest Mr. Kirby (father of Mrs. Trimmer, and the artist who had taught the king perspective) in a very malicious and mortifying manner, and the story was related to Mr. Galt by West, with a quiet, cold spite, peculiarly his own. Mr. Kirby came to the palace just as West was submitting his sketch for “Regulus” to the king. West was a true courtier, and knew well how to make a patron suggest his own subject. Kirby praised the picture, and hoped Mr. West intended to exhibit it. The Quaker slily replied that that depended on his majesty’s pleasure. The king, like a true confederate, immediately said, “Assuredly I shall be happy to let the work be shown to the public.” “Then, Mr. West,” said the perhaps too arrogant president, “you will send it to my exhibition?” “No!” said the king, and the words must have been thunderbolts to poor Kirby; “it must go to my exhibition.”[127] “Poor Kirby,” says West, “only two nights before, had declared that the design of[Pg 74] forming such an institution was not contemplated. His colour forsook him—his countenance became yellow with mortification—he bowed with profound humility, and instantly retired, nor did he long survive the shock!”

Mr. West is wrong, however, in the last statement, for his rival did not die till 1774. Mr. Kirby, a most estimable man, was originally a house-painter at Ipswich. He became acquainted with Gainsborough, was introduced by Lord Bute to the king, and wrote and edited some valuable works on perspective, to one of which Hogarth contributed an inimitable frontispiece.

Sir Robert Strange says that much of this intrigue was carried out by Mr. Dalton,[128] a print seller in Pall Mall, and the king’s librarian, in whose rooms the exhibition was held in 1767 and 1768.

Thus an American Quaker, a Swiss, and a Swede—(a gold-chaser, a coach-painter, an architect, and a third-rate painter, West)—ignobly established the Royal Academy. Many eminent men refused to join the new society. Allan Ramsay, Hudson, Scott the marine-painter, and Romney were opposed to it. Engravers (much to the disgrace of the Academy) were excluded; and worst of all, one of the new laws forbade any artist to be eligible to academic honours who did not exhibit his works in the Academy’s rooms: thus depriving for ever every English artist of the right to earn money by exhibiting his own works.[129]

The proportion of foreigners in the Academy was very large. The two ladies who became members (Angelica Kauffmann and Mrs. Moser) were both Swiss.[130]

[Pg 75]The other unlucky society, deprived of its share of the St. Martin’s Lane casts, etc., and shut out from the Academy, furnished a studio over the Cyder Cellars in Maiden Lane, struggled on till 1807, and then ceased to exist.[131]

The Academy, with all its tyranny and injustice, has still been useful to English art in perpetuating annual exhibitions which attract purchasers. But what did more good to English art than twenty academies was the king’s patronage of West, the spread of engraving, and the rise of middle-class purchasers, who rendered it no longer necessary for artists to depend on the caprice and folly of rich aristocratic patrons.

One word more about the art oligarchy. The first officers of the new society were—Reynolds, president; Moser, keeper; Newton, secretary; Penny, professor of painting; Sandby, professor of architecture; Wale, professor of perspective; W. Hunter, professor of anatomy; Chambers, treasurer; and Wilson, librarian. Goldsmith was chosen professor of history at a later period.

The catalogue of the first exhibition of the Royal Academy contains the names of only one hundred and thirty pictures: Hayman exhibited scenes from Don Quixote; Rooker some Liverpool views; Reynolds some allegorised portraits; Miss Kauffmann some of her tame Homeric figures; West his “Regulus” (that killed Kirby), and a Venus and Adonis; Zuccarelli two landscapes.

In 1838, the first year after the opening of the National Gallery, 1382 works of art, including busts and architectural[Pg 76] designs, were exhibited. Among the pictures then shown were—Stanfield’s “Chasse Marée off the Gulf-stream Light,” “The Privy Council,” by Wilkie; portraits of men and dogs, by Landseer; “The Pifferari,” “Phryne,” and “Banishment of Ovid,” by Turner; “A Bacchante,” by Etty; “Gaston de Foix,” by Eastlake; Allan’s “Slave Market,” Leslie’s “Dinner Scene from the Merry Wives of Windsor;” “A View on the Rhine,” by Callcott; Shee’s portrait of Sir Francis Burdett; portraits by Pickersgill; Maclise’s “Christmas in the Olden Time,” and “Olivia and Sophia fitting out Moses for the Fair;” “The Massacre of the Innocents,” by Hilton; and a picture by Uwins.[132]

Angelica Kauffmann and Biaggio Rebecca helped to decorate the Academy’s old council-chamber at Somerset House. The paintings still exist. Rebecca was an eccentric, conceited Italian artist, who decorated several rooms at Windsor, and offended the worthy precise old king by his practical jokes. On one occasion, knowing he would meet the king on his way to Windsor with West, he stuck a paper star on his coat. The next time West came, the king was curious to know who the foreign nobleman was he had seen—“Person of distinction, eh? eh?”—and was doubtless vexed at the joke.

Rebecca’s favourite trick was to draw a half-crown on paper, and place it on the floor of one of the ante-rooms at Windsor, laughing immoderately at the eagerness with which some fat courtier in full dress, sword and bag, would run and scuffle to pick it up.[133]

Fuseli took his place as Keeper of the Academy in 1805. Smirke had been elected, but George III., hearing that he was a democrat, refused to confirm the appointment. Haydon, who called on Fuseli in Berners Street in 1805, when he had left his father the bookseller at Plymouth, describes him as “a little white-headed, lion-faced man, in an old flannel dressing-gown tied round his waist with a piece of rope, and upon his head the bottom of Mrs. Fuseli’s[Pg 77] work-basket.” His gallery was full of galvanised devils, malicious witches brewing incantations, Satan bridging chaos or springing upwards like a pyramid of fire, Lady Macbeth, Paolo and Francesca, Falstaff and Mrs. Quickly.

Elsewhere the impetuous Haydon sketches him vigorously. Fuseli was about five feet five inches high, had a compact little form, stood firmly at his easel, painted with his left hand, never held his palette upon his thumb, but kept it upon his stone slab, and being very near-sighted and too vain to wear glasses, used to dab his beastly brush into the oil, and sweeping round the palette in the dark, take up a great lump of white, red, or blue, and plaster it over a shoulder or a face; then prying close in, he would turn round and say, “By Gode! dat’s a fine purple! it’s very like Correggio, by Gode!” and then all of a sudden burst out with a quotation from Homer, Tasso, Dante, Ovid, Virgil, or the Niebelungen, and say, “Paint dat!” “I found him,” says Haydon, “a most grotesque mixture of literature, art, scepticism, indelicacy, profanity, and kindness. He put me in mind of Archimago in Spenser.”[134]

When Haydon came first to town from Plymouth, he lodged at 342 Strand,[135] near Charing Cross, and close to his fellow-student, the good-natured, indolent, clever Jackson. The very morning he arrived he hurried off to the Exhibition, and mistaking the new church in the Strand for Somerset House, ran up the steps and offered his shilling to a beadle. When he at last found the right house, Opie’s Gil Blas and Westall’s Shipwrecked Sailor Boy were all the historical pictures he could find.

Sir Joshua read his first discourse before the Academy in 1769. Barry commenced his lectures in 1784, ended them in 1798, and was expelled the Academy in 1799. Opie delivered his lectures in 1807, the year in which he died. Fuseli began in 1801, and delivered but twelve lectures in all.

It was on St. George’s Day, 1771, that Sir Joshua Reynolds took the chair at the first annual dinner of the Royal[Pg 78] Academy. Dr. Johnson was there, with Goldsmith and Horace Walpole. Goldsmith got the ear of the company, but was laughed at by Johnson for professing his enthusiastic belief in Chatterton’s discovery of ancient poems. Walpole, who had believed in the poet of Bristol till he was laughed at by Mason and Gray, began to banter Goldsmith on his opinions, when, as he says, to his surprise and concern, and the dashing of his mirth, he first heard that the poor lad had been to London and had destroyed himself. Goldsmith had afterwards a quarrel with Dr. Percy on the same subject.

One day, while Reynolds was lecturing at Somerset House, the floor suddenly began to give way. Turner, then a boy, was standing near the lecturer. Reynolds remained calm, and said afterwards that his only thought was what a loss to English art the death of that roomful would have been.

On the death of Mr. Wale, the Professor of Perspective, Sir Joshua was anxious to have Mr. Bonomi elected to the post, but he was treated with great disrespect by Mr. Copley and others, who refused to look at Bonomi’s drawings, which Sir Joshua (as some maintained, contrary to rule) had produced at Fuseli’s election as Academician. Reynolds at first threatened to resign the presidency; but thought better of it afterwards.

In the catalogues in 1808 Turner’s name first appeared with the title of Professor of Perspective attached to it. His lectures were bad, from his utter want of language, but he took great pains with his diagrams, and his ideas were often original. On one celebrated occasion Turner arrived in the lecture-room late, and much perturbed. He dived first into one pocket, and then into another; at last he ejaculated these memorable words: “Gentlemen, I’ve been and left my lecture in the hackney-coach!”[136]

In 1779 O’Keefe describes a visit paid to Somerset House to hear Dr. William Hunter lecture on anatomy. He describes him as a jocose little man, in “a handsome modest” wig. A skeleton hung on a pivot by his side, and on his other hand stood a young man half stripped. Every[Pg 79] now and then he paused, to turn to the dead or the living example.[137]

In 1765, when Fuseli was living humbly in Cranbourn Alley, and translating Winckelmann, he used to visit Smollett, whose Peregrine Pickle he was then illustrating; and also Falconer, the author of The Shipwreck, who, being poor, was allowed to occupy apartments in Somerset House.[138] The poet was a mild, inoffensive man, the son of an Edinburgh barber. He had been apprenticed on board a merchant vessel, after which he entered the royal navy. In 1762 he published his well-known poem. He went out to India in 1769, in the Aurora, which is supposed to have foundered in the Mozambique Channel.[139] Falconer was a short thin man, with a hard-featured, weather-beaten face and a forbidding manner; but he was cheerful and generous, and much liked by his messmates. That hearty sea-song, “Cease, rude Boreas,” has been attributed to him.

Fuseli succeeded Barry as Lecturer on Painting in 1799, and became Keeper on the death of Wilton, the sculptor, in 1803. He died in 1825, aged eighty-four, and was buried in St. Paul’s, between Reynolds and Opie. Lawrence, Beechey, Reinagle, Chalon, Jones, and Mulready followed him to his stately grave. The body had previously been laid in state in Somerset House, his pictures of “The Lazar House” and “The Bridging of Chaos” being hung over the coffin.

When Sir Joshua died, in 1792, his body lay in state in a velvet coffin, in a room hung with sable, in Somerset House. Burke and Barry, Boswell and Langton, Kemble and John Hunter, Towneley and Angerstein came to witness the ceremony.

Where events are so interwoven as they are in topographical history, I hope to be pardoned if I am not always chronological in my arrangement, for it must be remembered that I have anecdotes to attend to as well as dates. Let me here, then, dilate on a cruel instance of misused academic[Pg 80] power. My story relates to a young genius as unfortunate as Chatterton, yet guiltless of his lies and forgeries, who died heart-broken by neglect more than half a century ago.

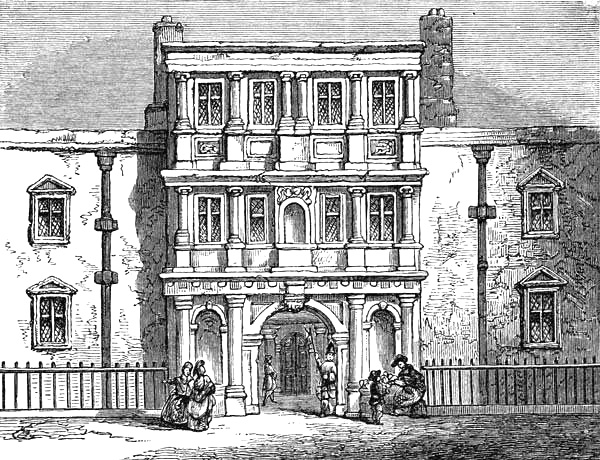

SOMERSET HOUSE FROM THE STRAND, 1777.

Procter, a young Yorkshire clerk, came up to London in 1777, and became a student of the Royal Academy. In 1783 he carried off a silver medal, and the next year won the gold medal for an historical picture. When Procter gained this last prize, his fellow-students, raising him on their shoulders, bore him downstairs, and then round the quadrangle of Somerset House, shouting out, “Procter! Procter!” Barry was delighted at this, and exclaimed with an oath, “Bedad! the lads have caught the true spirit of the ould Greeks.” Sir Abraham Hume bought Procter’s “Ixion,” which was praised by Reynolds. His colossal “Diomede”[Pg 81] the poor fellow had to break up, as he had no place to keep it in, and no one would buy it. In 1794 Mr. West, wishing that Procter should go to Rome as the travelling student, discovered him, after much inquiry, in poor lodgings in Maiden Lane. A day or two afterwards he was found dead in his bed. The Academicians had been, perhaps, just a little too late with their patronage.[140]

And now, when through grey twilight glooms I steal a glance as I pass by at that grave black figure of the river god, presiding solemn as Rhadamanthus over the central quadrangle of Somerset House, I sometimes dream I see little leonine Fuseli, stormy Barry, and courtly Reynolds pacing together the dim quadrangle that on these autumnal evenings, when the rifle drills are over, wears so lonely and purgatorial an aspect; and far away from them, in murky corners, I fancy I hear muttering the ghosts of Portuguese monks, while scowling at them, stalks by pale Sir Edmondbury, with a sword run through his shadowy body.

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:12:52 GMT