Haunted London, Index

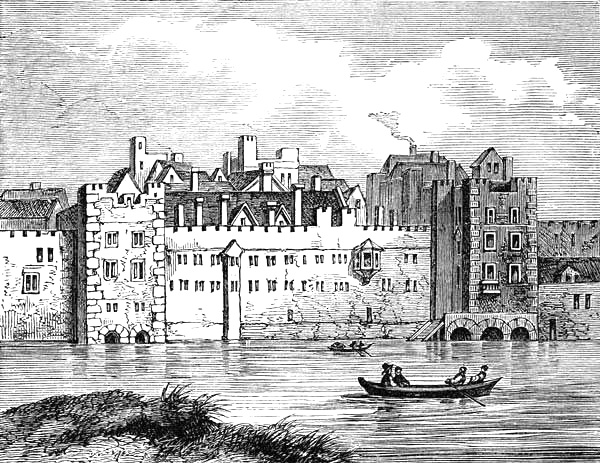

THE SAVOY FROM THE THAMES, 1650.

CHAPTER VI.

THE SAVOY.

“Their leaders, John Ball, Jack Straw, and Wat Tyler, then marched through London, attended by more than twenty thousand men, to the palace of the Savoy, which is a handsome building on the road to Westminster, situated on the banks of the Thames, and belonging to the Duke of Lancaster. They immediately killed the porters, pressed into the house, and set it on fire.”—Froissart’s Chronicles.

A minute’s walk down a turning on the south side of the Strand, and we are in the precinct of an old palace, and standing on royal property.

In a ramble by moonlight one cannot fail to meet under the churchyard trees in the Savoy, John of Gaunt, who[Pg 107] once lived there; John, King of France, who died there; George Wither, the poet, and sweet Mistress Anne Killigrew, who are buried there, and Chaucer, who was married there.

Down that steep, dray-traversed street, now so dull and lonely, kings and bishops, knights and ladies, have paced, and mobs have hurried with sword and fire. Now it is a congeries of pickle warehouses, printing offices, and glass manufactories.

Simon de Montfort, that ambitious Earl of Leicester who married the sister of Henry III., and whose father persecuted the Albigenses, dwelt in the Savoy. Here he must have first won the barons, the people, and the humbler clergy by his opposition to the extortions of the king and the bishops. Here for a time he must have all but reigned, till that fatal August day when he fell at Evesham. Simon was a friend of the monks, and after his death endless miracles were said to have been wrought at his grave,[191] as might have been expected.

The Savoy derives its foreign name from a certain Peter, Earl of Savoy, uncle of Eleanor, the daughter of Raymond, Count of Provence, and queen of that good man, but weak monarch, Henry III. This earl was the leader of that rapacious and insolent train of Frenchmen and Savoyards which followed Queen Eleanor to England, and drove Simon de Montfort and his impetuous barons to rebellion by their hunger for titles, lands, and benefices. In 30 Henry III. the king granted to Peter, Earl of Richmond and Savoy, all those houses in the Strand, adjoining the river, formerly belonging to Brian de Lisle, upon paying yearly to the king’s exchequer, at the Feast of St. Michael, three barbed arrows for all services.

In 1322 an Earl of Lancaster, then master of the Savoy, on the return of the Spensers, formed an alliance with the Scots, and broke out into open rebellion against Edward II. He was taken at Boroughbridge, led to Pontefract, and there beheaded. As he was led to execution on a bridleless pony, the mob pelted him with mud, taunting him as King[Pg 108] Arthur—the royal name he had assumed in his treasonable letters to the Scots.[192]

Earl Peter, in due time growing weary of stormy England, and sighing for his cool Savoy mountains, transferred his mansion to the provost and chapter of Montjoy (Fratres de Monte Jovis) at Havering-atte-Bower, a small village in Essex. At the death of the foolish king, his widow purchased the palace of the Savoy of the Montjoy chapter, as a residence for her son Edmund, afterwards Earl of Lancaster, to whom had been given the chief estates of the defeated Montfort.

His son Henry, Duke of Lancaster, repaired and partly rebuilt the palace, at an expense of upwards of 50,000 marks. From this potent lord it descended to Edward III.’s son, John of Gaunt (Ghent), who lived here in the splendour befitting the son of Edward III., the uncle of Richard II., and the father of a prince hereafter to become Henry IV.

It was in the chapel of this river-side palace (about 1360, Edward III.) that our great poet, Geoffrey Chaucer, married Philippa, daughter of a knight of Hainault and sister to a mistress of the Duke’s. He mentions his marriage in his poem of The Dream.[193] He says harmoniously—

“On the morrow,

When every thought and every sorrow

Dislodg’d was out of mine heart,

With every woe and every smart,

Unto a tent prince and princess

Methought brought me and my mistress.

****

With ladies, knighten, and squiers,

And a great host of ministers,

Which tent was church parochial.”

Those marriage bells have long since rung, the smoke of that incense has long since risen to heaven, yet we seldom pass the Savoy without thinking how the poet and his fair Philippa went

[Pg 109]

“To holy church’s ordinance,

And after that to dine and dance,

... and divers plays.”

It was to his great patron—“time-honoured” Lancaster, claimant, through his wife, of the throne of Castile—that Chaucer owed all his court favours, his Genoese embassy, his daily pitcher of wine, his wardship, his controllership, and his annuity of twenty marks. It was in this palace he must have imbibed his attachment to Wickliffe, and his hatred of all proud and hypocritical priests.

Buildings seem, like men, to be born under special stars. It was the fate of the Savoy to enjoy a hundred and forty years of splendour, and then to sink into changeless poverty and desolation. It was also its ill fate to be once sacked and once burnt. In 1378, under Richard II., its first punishment overtook it. John Wickliffe, a Yorkshireman, had been appointed rector of Lutterworth, in Leicestershire, by the favour of John of Ghent, who was delighted with a speech of Wickliffe in Parliament denying that King John’s tribute to the Pope necessarily bound King Edward III. The Papal bull for Wickliffe’s prosecution did not reach England till the king’s death, but Wickliffe was cited on the 19th of February, 1378, to appear before the Bishop of London at St. Paul’s. In the interval before his appearance he had promised the Parliament, at their request, to prove the legality of its refusal to pay tribute to the Pope.

On the day appointed Wickliffe appeared in Our Lady’s Chapel, accompanied by the Earl Marshall, Percy, and the Duke of Lancaster, who openly encouraged him, to the horror of the populace and the bitter rage of the priests. A quarrel instantly began by Courtenay, the Bishop of London, opposing a motion of the Earl Marshall that Wickliffe should be allowed a seat. The proud duke, pale with anger, whispered fiercely to the bishop that, “rather than take such language from him, he would drag him out of the church by the hair of his head.” The threat was heard by an unfriendly bystander, and it passed round the church in whispers. Rumour, with her thousand babbling tongues, was soon busy[Pg 110] in the churchyard, where the people had assembled, eager for the reformer’s condemnation. They instantly broke forth like hounds which have recovered a scent. It was at once proposed to break into the church and pull the duke from the judgment-seat. When he appeared at the door, he was received with ominous yells, and was chased and pelted by the mob. Furious and beside himself with rage, he instantly proceeded to Westminster, where the Parliament was sitting, and moved that from that day forth all the privileges of the citizens of London should be annulled, that they should no longer elect a mayor or sheriff, and that Lord Percy should possess the entire jurisdiction over them—a severe penalty, it must be owned, for pelting a duke with mud.

The following day, the citizens, hearing of this insolent proposal, snatched up their arms, and swore to take the proud duke’s life. After pillaging the Marshalsea, where Lord Percy resided, they poured down on the Savoy and killed a priest whom they took to be Percy in disguise. They then broke all the furniture and threw it into the Thames, leaving only the bare walls standing. While the mob were shouting at the windows, feeding the river with torrents of spoiled wealth, or cutting the beds and tapestry to pieces, the duke and Lord Percy, who had been dining with John of Ypres, a merchant in the City, escaped in disguise by rowing up the river to Kingston in an open boat. Eventually, at the entreaties of the Bishop of London, who pleaded the sanctity of Lent, the rioters dispersed, having first hung up the duke’s arms in a public place as those of a traitor. The Londoners finally appeased their opponent by carrying to St. Paul’s a huge taper of wax, blazoned with the duke’s arms, which was to burn continually before the image of Our Lady in token of reconciliation.

This John of Gaunt, fourth son[194] of Edward III., married Blanche, daughter of Henry, Duke of Lancaster, who died of the plague in 1360, John succeeding to the title in right of his wife. He married his daughter Philippa to the King of Portugal, and his daughter Catharine to the Infant of[Pg 111] Spain. From Henry Plantagenet, fourth Earl and first Duke of Lancaster, the Savoy descended to this John of Ghent, who married that amiable princess, Blanche Plantagenet, daughter and co-heir of Earl Henry.

Into this same king-haunted precinct John of France, after the slaughter at Poitiers, was brought with chivalrous and almost ostentatious humility by the Black Prince. One thousand nine hundred English lances had routed with great slaughter eight thousand French. The lanes and moors of Maupertuis were choked with dead knights; the French king had been wounded, beaten to the ground, and taken prisoner, together with his son Philip, by a gentleman of Artois.[195] Sailing from Bordeaux, the Black Prince arrived at Sandwich with his prisoner, and was received at Southwark by the citizens of London on May 5, 1357. Triumphal arches were erected, and tapestry hung from every window. The King of France rode like a conqueror on a richly trapped cream-coloured horse, while by his side sat the young prince on a small black palfrey. Some hours elapsed before the procession could reach Westminster Hall, where King Edward was surrounded by his prelates, knights, and barons. When John entered, our king arose, embraced him, and led him to a splendid banquet prepared for him. The palace of the Savoy was allotted to King John and his son, till his removal to Windsor.

Here the royal Frenchman may have been when he heard the tidings of the ferocity of the Jacquerie, and of the dreadful riots in his capital. To the Savoy he returned when his son, the Duke of Anjou, broke his parole and fled to Paris, desirous to exculpate himself of this dishonour, and to arrange for a crusade to recover Cyprus from the Turk.[196] To his council, dissuading him from returning, like a second Regulus, to captivity and perhaps death, the king addressed these memorable words—“If honour were banished from every other place, it should at least find an asylum in the breast of kings.”

[Pg 112]John was affectionately received by the chivalrous Edward, and again returned to his old quarters in the Savoy, with his hostages of the blood royal—“the three lords of the fleur-de-lys.” Here he spent several weeks in giving and receiving entertainments; but before he could proceed to business, he was attacked with a dangerous illness, and expired in 1364. His obsequies were performed with regal magnificence, and his corpse was sent with a splendid retinue to be interred at St. Denis.

When treaties are broken by statesmen, or unjust wars declared, let the reader go to the Savoy, and think of that brave promise-keeper, King John of France.

During the latter years of King Edward III., John of Gaunt became very unpopular. “The good Parliament” (1376) remonstrated against the expense of his unsuccessful wars in Spain, Scotland, and France, and against the excessive taxation. The duke imprisoned the Speaker, and banished wise William of Wyckeham from the king’s person, but in vain attempted to alter the law of succession.

In Wat Tyler’s rebellion the duke’s palace was the first to be destroyed. A refusal to pay oppressive poll-tax led to a riot at Fobbing, a village in Essex; from this place the flame spread like wildfire through the whole county, and the people rose, led by a priest named Jack Straw. At Dartford, a tiler bravely beat out the brains of a tax-collector who had insulted his daughter. Kent instantly rose, took Rochester Castle, and massed together at Maidstone, under Wat, a tiler, and Ball, a preacher. In a few days a hundred thousand men, rudely armed with clubs, bills, and bows, poured over Blackheath and hurried on to London.[197] In Southwark they demolished the Marshalsea and the King’s Bench; then they sacked Lambeth Palace, destroyed Newgate, fired the house of the Knights Hospitallers at Clerkenwell, and that of the Knights of St. John at Highbury, and seizing the Tower, beheaded an archbishop and several knights. All Flemings hidden in churches were dragged out and put to death. Yet, with all this intoxication of new[Pg 113] liberty, the claims of these Kentish men were simple and just. They demanded—The abolition of slavery; the reduction of rent to fourpence an acre; the free liberty of buying and selling in all fairs and markets; and lastly a general pardon.

At the great bivouacs at Mile End and on Tower Hill, Wat Tyler’s men required all recruits to swear to be true to King Richard and the Commons, and to admit no monarch of the name of John.[198] This last clause of the oath was aimed at John of Gaunt, to whom the people attributed all their misery. On June 13, 1381, a deluge of billmen, bowmen, artisans, and ploughmen rolled down on the Savoy. The duke was at the time negotiating with the Scots on the Borders, while his castles of Leicester and Tutbury were being plundered. The attack was sudden, and there was no defence. A proclamation had previously been made by Wat Tyler, that, as the common object was justice and not plunder, any one found stealing would be put to death.

For beauty and stateliness of building, as well as all manner of princely furniture, there was, says Holinshed, no palace in the realm comparable to the duke’s house that the Kentish and Essex men burnt and marred. They tore the silken and velvet hangings; they beat up the gold and silver plate, and threw it into the Thames; they crushed the jewels and mortars, and poured the dust into the river. One of the men—unfortunate rogue!—being seen to slip a silver cup into the breast of his doublet, was tossed into the fire and burnt to death, amid shouts and “fell cries.”[199] The cellars were ruthlessly plundered, probably in spite of Wat Tyler, and thirty-two of the poor wretches, buried under beams and stones, were either starved or suffocated. In the wildest of the storm, some barrels were at last found which were supposed to contain money. They were flung into the huge bonfire; in an instant they exploded, blew up the great hall, shook down several houses, killed many men, and reduced the palace to ruins. That was on the 13th; on the 15th, the Essex men had dispersed; and Wat Tyler,[Pg 114] the impetuous reformer, during a conference with the king in Smithfield, was slain by a sudden blow from the sword of Lord Mayor Walworth.

John of Gaunt died at the Bishop of Ely’s palace in Holborn, at Christmas 1398—his old home being now a ruin—and he was buried on the north side of the high altar of Saint Paul’s, beside the Lady Blanche, his first wife. Instantly on his death, the wilful young king, to the rage of the people, seized on all his uncle’s lands, rents, and revenues, and banished the duke’s attorney, who resisted his shameless theft. Amongst this pile of plunder the Savoy must have also passed.

The Savoy had bloomed, and after the bloom came in its due time the “sere and yellow leaf.” The precinct must have remained a waste during the Wars of the Roses;[200] but its blackened ruins preached their silent lesson in vain to the turbulent and tormented Londoners.

In the reign of that dark and wily king, Henry VII., sunshine again fell on the Savoy. That prince, who was fond of erecting convents, founded on the old site a hospital, intended to shelter one hundred poor almsmen. It was not, however, finished when he died, nor was it completed till the fifteenth year of his son’s reign (1524), the year in which the French were driven out of Italy.

The hospital, which was dedicated to John the Baptist, was in the form of a cross, and over the entrance-gate, facing the Strand, was the following insipid inscription:—

“Hospitium hoc inopi turba Savoia vocatum,

Septimus Henricus solo fundavit ab imo.”

The master and four brethren were to be priests and to officiate in turns, standing day and night at the gate to invite in and feed any poor or distressed persons who passed down the river-side road. If those so received were pilgrims or travellers, they were to be dismissed the next morning[Pg 115] with a letter of recommendation to the next hospital, and with money to defray their expenses on the journey.

In the reign of Edward VI., part of the revenues of the new hospital, to the value of six hundred pounds, was transferred to Bridewell prison and Christ’s Hospital school for poor orphan children; for already abuses had crept in, and indiscriminate charity had led to its usual melancholy results. The old palace had become no mere shelter for the deserving poor, but a den of loiterers, sham cripples, and vagabonds of either sex, who begged all day in the fields and came to the Savoy to sleep and sup.[201]

Queen Mary, whose Spanish blood made her a friend to all monastic institutions, re-endowed the unlucky place with fresh lands; but it went on in its old courses till the twelfth year of Elizabeth, who suddenly pounced in her own stern way on the nest of rogues, and, to the terror of sinecurists, deprived Thomas Thurland, then master, of his office, for corruption and embezzlement of the hospital estates.

We hear nothing more of the unlucky and neglected Hospital of St. John till the Restoration, when Dr. Henry Killigrew was appointed master, much to the chagrin and disappointment of the poet Cowley, to whom the sinecure had been promised by Charles I. and Charles II.

Cowley, the clever son of a London stationer, had been secretary to the queen-mother, but returning as a spy to England, was apprehended, and upon that made his peace with Cromwell. This latter fact the Royalists never forgave, and considering his play of The Cutter of Colman Street as caricaturing the old roystering Cavalier officers, they damned his comedy, lampooned him, and gave the Savoy to Killigrew, father of the court wit. Upon this the mortified poet wrote his poem of “The Complaint,”[202] wherein he calls the Savoy the Rachel he had served with “faith and labour for twice seven years and more,” and querulously describes himself as left alone gasping on the naked beach, while all his fellow voyagers had marched up to possess the promised land. The poem, though ludicrously querulous, contains some[Pg 116] lines, such as the following, which are truly beautiful. The muse is reproaching the truant poet.

“Art thou returned at last,” said she,

“To this forsaken place and me,

Thou prodigal who didst so loosely waste,

Of all thy youthful years, the good estate?

Art thou return’d here to repent too late,

And gather husks of learning up at last,

Now the rich harvest-time of life is past,

And winter marches on so fast?”

With this farewell lament Cowley withdrew “from the tumult and business of the world,” to his long-coveted retirement[203] at pleasant, green Chertsey, where, seven years after, he died.

The Savoy, always an abused sinecure, that made the master a rogue and its inmates professional beggars, was finally suppressed in the reign of Queen Anne.[204] It was then used as a barrack for five hundred soldiers, and as a deserters’ prison, till the approaches to Waterloo Bridge rendered its removal necessary.

Savoy Street occupies the site of the old central Henry VII.’s Tudor gate. Coal wharves cover the site of the ancient front of the hospital, and the houses in Lancaster Place, leading to Waterloo Bridge, another part of its area.

In 1661, the year after the restoration of Charles II., a celebrated conference between the Church of England bishops and the Presbyterian divines took place, with very small result, in the Bishop of London’s lodgings in the Savoy. Among the twelve bishops were Sheldon and Gauden, the author of Ikon Basilike: among the Presbyterians Baxter, Calamy, and Reynolds. They were to revise the Liturgy, and to discuss rules and forms of prayer; but there was so much distrust and reserve on both sides, that at the end of two months the conference came to an untimely end.[205] It was the bishops’ hour of triumph, and no[Pg 117] concessions could be expected from them after their many mortifications. In the same year Charles II. established a French church in the Savoy, and Dr. Durel preached the first sermon to the foreign residents in London, July 14, 1661.[206]

In Queen Anne’s time, after its suppression, the Savoy became, like the Clink and Whitefriars, a sanctuary for fraudulent debtors. On one occasion, in 1696, a creditor entering that nest of thieves to demand a debt, was tarred and feathered, carried in a wheelbarrow into the Strand, and there bound to the May-pole; but some constables coming up dispersed the rabble and rescued the tormented man from his persecutors.[207]

Strype, writing about 1720 (George I.), describes the Savoy as a great ruinous building, divided into several apartments. In one a cooper stored his hoops and butts; in another there were rooms for deserters, pressed men, Dutch recruits, and military prisoners. Within the precinct there was the king’s printing-press, where gazettes, proclamations, and Acts of Parliament were printed; and also a German Lutheran church, a French Protestant church, and a Dissenting chapel; besides “harbours for refugees and poor people.”[208] The worthy writer thus describes the hall of the old hospital:—

“In the midst of its buildings is a very spacious hall, the walls three foot broad, of stone without and brick and stone inward. The ceiling is very curiously built with wood, having knobs in one place hanging down, and images of angels holding before their breasts coats of arms, but hardly discoverable. One is a cross gules between four stars, or else mullets. It is covered with lead, but in divers places open to the weather. Towards the east end of the hall is a fair cupola with glass windows, but all broken, which makes it probable the hall was as long again, since cupolas are wont to be built about the middle of great halls.”

[Pg 118]In 1754 (George II.) clandestine marriages were performed at the Savoy church; and the advantages of secrecy, privacy, and access by water were boldly advertised in the papers of the day. The Public Advertiser of January 2, 1754, contains the following impudent and touting advertisement:—

“By Authority.—Marriages performed with the utmost privacy, secrecy, and regularity, at the ancient royal chapel of St. John the Baptist in the Savoy, where regular and authentic registers have been kept from the time of the Reformation (being two hundred years and upwards) to this day. The expense not more than one guinea, the five shilling stamp included. There are five private ways by land to this chapel, and two by water.”

At this time the Savoy was still a large cruciform building, with two rows of mullioned windows facing the Thames; a court to the north of it was called the Friary. The north front, the most ornamented, had large pointed windows and embattled parapets, lozenged with flint.

At the west end, in 1816, stood the guard-house, or military prison, its gateway secured by a strong buttress, and embellished with Henry VII.’s arms and the badges of the rose and the portcullis: above these were two hexagonal oriel windows.

In 1816, when the ruins were to be removed, crowds thronged to see the remains of John of Gaunt’s old palace.[209] The workmen found it difficult to destroy the mossy and ivy-covered walls and the large north window; the masses of flint, stone, and brick being eight or ten feet thick. The screw-jack was powerless to destroy the work of Chaucer’s time. The masons had to dig, pickaxe holes, and loosen the foundations, then to drive crowbars into the windows and fasten ropes to them, so as to pull the stones inwards. The outer buttresses would in any other way have defied armies.

Some of the stone was soft and white. This, according to tradition, was that brought from Caen by Queen Mary.[Pg 119] The industrious costermongers discovered this, and cut it into blocks to sell as hearthstones. A fire about 1777 had thrown down much of the hospital, so that the old level was fifteen or twenty feet deeper. The vaults and subterranean passages were unexplored. The wells were filled up. The workmen then pulled down the German chapel, which stood next Somerset House, and the red-brick house in the Savoy Square that was used for barracks. “The entrance,” says a writer of 1816, “to the Strand or Waterloo Bridge will be spacious, and the houses in the Strand now only stop the opening.”[210]

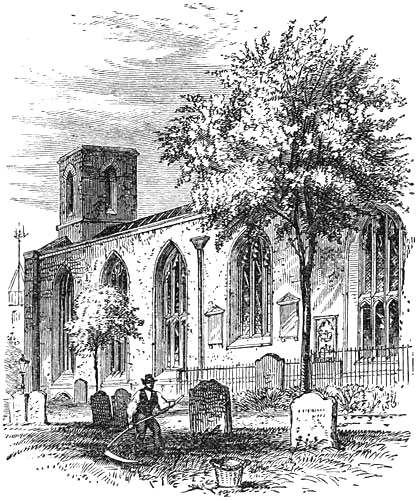

The Chapel of St. Mary, Savoy, is a late and plain Perpendicular structure, with a fine coloured ceiling. This small, quiet chapel holds a silent congregation of illustrious dead.

THE SAVOY CHAPEL.

Here are interred Sir Robert and Lady Douglas (temp. James I.); the Countess of Dalhousie, daughter of Sir Allen Apsley, Lieutenant of the Tower, and sister to that admirable wife, Mrs. Hutchinson, who died in 1663; William Chaworth, who died in 1582, a member of that Nottinghamshire family, one of whom, Lord Byron’s predecessor, killed in a tavern duel; and Mrs. Anne Killigrew, who died in[Pg 120] 1685, the paintress and poetess on whom Dryden wrote an extravagant but glorious ode, beginning—

“That youngest virgin daughter of the skies,

Made in the last promotion of the blest.”[211]

This accomplished young lady was daughter of Dr. Henry Killigrew, and niece of Thomas Killigrew the wit, of whom Denham, the poet, bitterly said—

“Had Cowley ne’er spoke, Killigrew ne’er writ,

Combined in one they’d made a matchless wit.”

The father of Mistress Killigrew was author of a tragedy called The Conspiracy, which both Ben Jonson and Lord Falkland eulogised. Even old Anthony Wood says, in his own quaint way, that this lady “was a Grace for beauty, and a Muse for wit.”[212]

We must add to this list Sir Richard and Lady Rokeby, who died in 1523, and Gawin Douglas, that good Bishop of Dunkeld who first translated Virgil into Lowland Scotch. He was pensioned by Henry VIII., was a friend of Polydore Virgil, and died of the plague in London in 1521. The brass is on the floor, about three feet south of the stove in the centre of the chapel.[213]

Dr. Cameron, the last victim executed for the daring rebellion of 1745, lies here also in good company among knights and bishops. His monument, by M. L. Watson, was not erected till 1846. Here, too, is that great admiral of Elizabeth—George, third Earl of Cumberland, who used to wear the glove which his queen had given him, set in diamonds, in his tilting helmet. He died in the Duchy House in the Savoy, October 3, 1605; but his bowels alone were buried here, the rest of his body lies at Skipton. He was the father of the brave, proud Countess, who, when Charles II.’s secretary pressed on her notice a candidate for Appleby, wrote that celebrated cannon-shot of a letter:—

[Pg 121]“I have been bullied by an usurper; I have been neglected by a court, but I will not be dictated to by a subject. Your man shan’t stand.

“Anne, Dorset, Pembroke, and Montgomery.”

Here also there is a tablet to the memory of Richard Lander, the traveller, originally a servant of that energetic discoverer Captain Clapperton, who was the first to cross Africa from Tripoli and Benin. Lander had the honour also of first discovering the course of the Niger. He died in February 1834, from a gunshot-wound, at Fernando Po, aged only thirty-one. Such are the lion-men who extend the frontiers of English commerce.

In the Savoy reposes a true poet, but an unhappy man—George Wither, the satirist and idyllist, who died in 1667, and lies here between the east door and the south end of the chapel.[214] He was one of Cromwell’s major-generals, and had a hard time of it after the Restoration. It was to save Wither’s life that Denham used that humorous petition—“As long as Wither lives I should not be considered the worst poet in England.”

Wither anticipated Wordsworth in simple earnestness and a regard for the humblest subjects. The soldier-poet himself says—

“In my former days of bliss,

Her divine skill taught me this:

That from everything I saw

I could some invention draw,

And raise pleasure to her height

Through the meanest object’s sight,

By the murmur of a spring,

By the least bough’s rustling.”[215]

These charming lines were written when Wither lay in the Marshalsea, imprisoned for writing a satire—Abuses stripped and whipped.

In the same church lies one of the smallest of military heroes—Lewis de Duras, Earl of Feversham, who died in the reign of Queen Anne. He was nephew of the great Turenne, and was one of the few persons present when Charles II. [Pg 122]received extreme unction. He commanded, or rather followed, King James II.’s troops at Sedgemoor, in 1685, and at that momentous crisis “thought only of eating and sleeping.”[216] Upon this shambling general the Duke of Buckingham wrote one of his latest lampoons.[217]

In 1552 the first manufactory of glass in England was established at the old Savoy House. It was here that, in 1658, the Independents met and drew up their famous Declaration of Faith. In 1671 the Royal Society’s publications were printed here. In Dryden’s time, the wounded English sailors who had been mangled by Van Tromp’s and De Ruyter’s shot were nursed here. The good and witty Fuller, who wrote the Worthies lectured here. Half-crazed Alexander Cruden, who compiled the laborious Concordance to the Bible, lived here; and here grinding Jacob Tonson had a warehouse.

In 1843 the Queen repaired the Savoy Chapel, in virtue of her being the patron of it. The duty, indeed, fell upon the Crown, for the chapel stood in the Liberty of the Duchy of Lancaster, and the office of the Duchy is in Lancaster Place, to the right as you approach Waterloo Bridge.

In July 1864 the Savoy Chapel was unfortunately destroyed by a fire occasioned by an explosion of gas. The coloured ceiling, the altar window, containing a figure of St. John the Baptist, and a solitary niche with some tabernacle work at the east end, all perished. It was shortly afterwards restored and decorated afresh throughout, at the cost of Her Majesty.

Mr. George Augustus Sala has admirably sketched the present condition of the Precinct,—its almost solemn silence and its gravity,—its loneliness, as of Juan Fernandez, Norfolk Island, or Key West,[218] although on the very verge of the roaring world of London, and but five minutes’ walk from Temple Bar.

The royal property is chiefly covered now by shops,[Pg 123] public-houses, and printing-offices. The Precinct still retains traditions of the vagabond squatters who, till about the middle of the last century, assumed possession of the ruinous tenements in the Savoy, till the Footguards turned them out, and the houses were pulled down, rebuilt, and let to respectable tenants.

The old churchyard has long since been sealed up by the Board of Health, but the trees and grass still flourish round the old stones. Clean-shaved, nattily dressed actors come to this quiet purlieu to study their parts. Musicians of theatrical orchestras, penny-a-liners, and printers haunt the bar of the Savoy tavern. Those quiet houses with the white door-steps, shining brass plates and green blinds, are inhabited by accountants’ clerks, retired and retiring small tradesmen, and commission agents interested in pale ale, pickles, and Wallsend coals.

“So,” says Mr. Sala, “run the sands of life through this quiet hour-glass; so glides the life away in the old Precinct. At its base a river runs for all the world; at its summit is the brawling, raging Strand; on either side are darkness and poverty and vice, the gloomy Adelphi arches, the Bridge of Sighs that men call Waterloo. But the Precinct troubles itself little with the noise and tumult; it sleeps well through life without its fitful fever.”

Wearied of its old grandeur, pondering, as old men ponder, over its dead kings—for Wat Tyler and his Kentish men need no Riot Act to quiet them now—the Savoy and its crowned ghosts drift on with our methodical planet, meekly awaiting the death-blow that time must some day inflict.

Tait Wilkinson’s father was a minister of the Savoy. Garrick helped to transport him by informing against him for illegally performing the marriage ceremony. In return, Garrick helped forward the son—“an exotic,” as he called him, rather than an actor—but a wonderful mimic, not only of voice and manner, but even of features. He used to reproduce Foote’s imitations of the older actors—as Mathews afterward imitated Wilkinson, who in his time had imitated Foote, to that impudent buffoon’s great vexation.

[Pg 124]The Examiner, whose office is near Waterloo Bridge, was started by Leigh Hunt and his brother John in 1808. It began by boldly asserting the necessity for reform, lampooning the Regent, and attacking the cant and excesses of Methodism. In 1812 both the Hunts were found guilty of having called the Prince Regent “the Prince of Whales” and “a fat Adonis of fifty,” and were sentenced to two years’ imprisonment in Horsemonger Lane gaol, and to pay a fine of £500. At a later period, Hazlitt joined the paper, and wrote for it the essays reprinted (in 1817) under the title of The Round Table.[219] Close to it is the office of the Spectator, another paper of the same calibre and class, and more important than the Examiner now, though its early history is not so interesting.

Waterloo Bridge, one of those marvels built by the industrious simple-hearted John Rennie, was opened by the Prince Regent in 1817. Dupin declared it was a colossal monument worthy of Sesostris or the Cæsars; and what most struck Canova in England was that the foolish Chinese Bridge then in St. James’s Park should be the production of the Government, while Waterloo Bridge was the result of mere private enterprise.[220] The bridge did not settle more than a few inches after the centres were struck.

The project of erecting the Strand Bridge, as it was first called, was started by a company in 1809, a joint-stock-fever year. Rennie received £1000 a year for himself and assistants, or £7: 7s. a day, and expenses. The bridge consists of nine arches, of 120 feet span, with piers 20 feet thick, the arches being plain semi-ellipses, with their crowns 30 feet above high water. Over the points of each pier are placed Doric column pilasters, after a design taken from the Temple of Segesta in Sicily. In the construction of the bridge the chief features of Rennie’s management were the following:—The employment of coffer-dams in founding the piers; new methods of constructing, floating, and fixing the centres; the introduction and working of Aberdeen granite to an [Pg 125]extent before unknown; and the adoption of elliptical stone arches of an unusual width.

Nearly all the bur stone was brought to the bridge by one horse, called “Old Jack.” On one occasion the driver, a steady man, but too fond of his morning dram, kept “Old Jack” waiting a longer time than usual at the public-house, upon which he poked his head in at the open door, and gently drew out his master by the coat collar.[221]

Rennie, the architect of the three great London bridges, the engineer of the Plymouth Breakwater and of the London and East India Docks, and a drainer of the Fens, was the son of a small farmer in East Lothian, and was born in 1761.[222]

THE SAVOY PRISON, 1793.

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:12:52 GMT