Haunted London, Index

CHAPTER VII.

FROM THE SAVOY TO CHARING CROSS.

Old York House stood on the site of Buckingham and Villiers Streets. In ancient times, York House had been the inn of the Bishops of Norwich. Abandoned to the crown, King Henry VIII. gave the place to that gay knight Charles Brandon, the husband of his beautiful sister Mary, the Queen of France. When the Church rose again and resumed its scarlet pomp, the house was given to Queen Mary’s Lord Chancellor, Nicholas Heath, Archbishop of York, in exchange for Suffolk House in Southwark, which was presented by Queen Mary to the see of York in [Pg 127]recompense for York House, Whitehall, taken from Wolsey by her father. On the fall of that minister, once more a change took place, and the house passed to the Lord Keeper, Sir Nicholas Bacon, who rented it of the see of York.

In this house the great Francis Bacon was born, on the 22d of January, 1561. York House stood near the royal palace, from which it was parted by lanes and fields. Its courtyard and great gates opened to the street. The main front, with its turrets and water stair, faced the river. The garden, falling by an easy slope to the Thames, commanded a view as far south as the Lollards’ Tower at Lambeth, as far east as London Bridge. “All the gay river life[223] swept past the lawn, the salmon-fishers spreading their nets, the watermen paddling gallants to Bankside, and Shakspere’s theatre, the city barges rowing past in procession, and the queen herself, with her train of lords and ladies, shooting by in her journeys from the Tower to Whitehall Stairs. From the lattice out of which he gazed, the child could see over the palace roof the pinnacles and crosses of the old abbey.”

The Lord Keeper Pickering died at York House in 1596, and Lord Chancellor Egerton in 1616 or 1617. In 1588 it is supposed the Earl of Essex tried to obtain the house, as Archbishop Sandys wrote to Burghley begging him to resist some such demand. Essex was in ward here for six months, fretting under the care of Lord Keeper Egerton.

“York House was the scene,” says a clever pleader for a great man’s good fame, “of Bacon’s gayest hours, and of his sharpest griefs—of his highest magnificence, and of his profoundest prostration. In it his studious childhood passed away. In it his father died. On going into France, to the court of Henry IV., he left it a lively, splendid home; on his return from that country, he found it a house of misery and death. From its gates he wandered forth with his widowed mother into the world. Though it passed into[Pg 128] other hands, his connection with it never ceased. Under Egerton its gates again opened to him. It was the scene of that inquiry into the Irish treason when he was the queen’s historian. During his courtship of Alice Barnham, York House was his second home. In one of its chambers he watched by the sick-bed of Ellesmere, and on Ellesmere’s surrender of the Seals, presented the dying Chancellor with the coronet of Brackley. It became his own during his reign as Keeper and Chancellor. From it he dated his great Instauration; in its banqueting-hall he feasted poets and scholars; from one of its bed-rooms he wrote his Submission and Confession; in the same room he received the Earls of Arundel, Pembroke, and Southampton, as messengers from the House of Lords; there he surrendered the Great Seal. To regain York House, when it had passed into other hands, was one of the warmest passions of his heart, and the resolution to retain it against the eager desires of Buckingham was one of the secret causes of his fall.”

“No,” said the fallen great man; “York House is the house wherein my father died and wherein I first breathed, and there will I yield my last breath, if it so please God, and the king will give me leave.”[224]

Some of the saddest and some of the happiest events of Bacon’s life must have happened in the Strand. From thence he rode, sumptuous in purple velvet from cap to shoe, along the lanes to Marylebone Chapel, to wed his bride Alice Barnham.

York House was famous for its aviary, on which Bacon had expended £300. It was in the garden here that we are told the Chancellor once stood looking at the fishers below throwing their nets. Bacon offered them so much for a draught, but they refused. Up came the net with only two or three little fish; upon which his lordship told them that “hope was a good breakfast, but an ill supper.”[225]

It was on the death of his friend, Lord Chancellor [Pg 129]Ellesmere, and on his own installation, that Bacon bought the lease of York House from the former’s son, the first Earl of Bridgewater. He found the rooms vast and naked. His friends and votaries furnished the house, giving him books and drawings, stands of arms, cabinets, jewels, rings, and boxes of money. Lady Cæsar contributed a massive gold chain, and Prince Charles a diamond ring.

Bacon, when young, had been often taken to court by his father; and the queen, delighting in the gravity and wisdom of the boy, used to call him her “young Lord Keeper.” Even then his mind was philosophically observant; and it is said that he used to leave his playmates in St. James’s Fields to try and discover the cause of the echo in a certain brick conduit.[226]

At Durham House, on January 22, 1620, the year in which he published his magnum opus, the Novum Organon, and a twelvemonth before his disgrace, Bacon gave a grand banquet to his friends. Ben Jonson was one of the guests, and is supposed to have himself recited a set of verses, in which he says—

“Hail th’ happy genius of the ancient pile!

How comes it that all things so about thee smile,—

The fire, the wine, the men?—and in the midst

Thou stand’st as if some mystery thou didst.

“England’s High Chancellor, the destined heir,

In his soft cradle to his father’s chair,

Whose even thread the Fates spin round and full,

Out of their choicest and their richest wool.

’Tis a brave cause of joy. * *

Give me a deep-crowned bowl, that I may sing,

In raising him, the wisdom of my king.”

Who till he dies can boast of having been happy? The year after, the king’s anger fell like an axe upon the great courtier. Solitary and comfortless at Gorhambury, Bacon petitioned the Lords in almost abject terms to be allowed to return to York House, where he could advance his studies and consult his physicians, creditors, and friends, so that “out of the carcass of dead and rotten greatness, as out of[Pg 130] Samson’s lion, there may be honey gathered for future times.” Sir Edward Sackville prayed him in vain to remove his straitest shackles by surrendering York House to the king’s favourite; and so did his creditor, Mr. Meautys, who, says Bacon, used him “coarsely,” and meant “to saw him asunder.” “The great lords,” says Meautys, “long to be in York House. I know your lordship cannot forget they have such a savage word among them as fleecing.” This word has grown tame in modern times, but it had a terrible significance in those days, when it hinted at flaying.

An episode about Bacon’s younger days may be pardoned here. The Gray’s Inn Chambers occupied by Bacon were in Coney Court, looking over the gardens and past St. Pancras Church to Hampstead Hill. They are no longer standing. The site of them was No. 1 Gray’s Inn Square. Bacon began to keep his terms at the age of eighteen, in June 1579. His uncle Burleigh was bencher in this inn, and his cousins, Robert, Cecil, and Nicholas Trott, students. In his latter days, when Attorney-General, and even when Lord Chancellor, he retained a lease of his old rooms in Coney Court. He was called to the bar when he was twenty-one, in 1582; and as soon as he was called he appeared in Fleet Street in his serge and bands, as a sign that he was going to practise for his bread. At the close of his first session, however, he was raised to the bench. Bacon always remained attached to Gray’s Inn; he laid out the gardens, planted the elm-trees, raised the terrace, pulled down and rebuilt the chambers, dressed the dumb show, led off the dances, and invented the masques.[227]

After Lord Bacon’s disgrace, the first Duke of Buckingham of the Villiers family borrowed the house from Toby Mathew, the courtly archbishop of York, in hopes of a final exchange, which did eventually take place.[228] In 1624, two years before Bacon’s death, a bill was passed to enable the king to exchange some lands for York House, so coveted by his proud favourite. Buckingham soon partially pulled[Pg 131] down the old mansion, and lined the walls of his temporary structure with huge mirrors. Here he entertained the foreign ambassadors. Of all his splendour, the only relic left is the water gate usually ascribed to Inigo Jones.

This Duke of Buckingham, the “Steenie” of King James, and of Scott’s Fortunes of Nigel, was the younger son of a poor knight, who won James I. by his personal beauty, vivacity, and accomplishments—by his dancing, jousting, leaping, and masquerading. At first page, cupbearer, and gentleman of the bedchamber, he rose to power on the disgrace of Carr.

It was at York House—“Yorschaux,” as he calls it, with the usual insolence and carelessness of his nation—that Bassompierre visited the duke in 1626. He praises the mansion as more richly fitted up than any other he had ever seen.[229] Yet the duke did not live here, but at Wallingford House, on the site of the Admiralty, keeping York House for pageants and levees, till Felton’s knife severed his evil soul from his body, August 23, 1628. His son, the Zimri of Dryden, was born at Wallingford House.

The “superstitious pictures” at York House were sold in 1645,[230] and the house given by Cromwell to General Fairfax, whose daughter married the second and last Duke of Buckingham, of the Villiers line, the favourite of Charles II., the rival of Rochester, the plotter with Shaftesbury, the selfish profligate who drove Lee into Bedlam and starved Samuel Butler.

In 1661 the galleries of York House were famous for the antique busts and statues that had belonged to Rubens on his visit to this country, when he painted James I. in jackboots being hauled heavenward by a flock of angels. In the riverside gardens—not far, I presume, from the water gate—stood John of Bologna’s “Cain and Abel,” which the King of Spain had given to Prince Charles on his luckless visit to Madrid, and which Charles had bestowed on his dangerous favourite.[231]

[Pg 132]The great rooms, even then emblazoned with the lions and peacocks of the Villiers and Manners families, were traversed by Evelyn, who describes the house and gardens as much ruined through neglect. Pepys also, who thrust his nose into every show-place, went to York House when the Russian ambassador was there, and rapturously and poetically vows he saw “the remains of the noble soul of the late Duke of Buckingham appearing in the house in every place, in the door-cases and the windows,”[232]—odd places for a noble soul to make its abode!

The Duke of Buckingham, in King Charles’s days, had turned York House into a treasury of art. He bought Rubens’s private collection of pictures for £10,000, Sir Henry Wotten having purchased them for him at Venice. He had seventeen Tintorets, and thirteen works of Paul Veronese. For an “Ecce Homo” by Titian, containing nineteen figures as large as life, he refused £7000 from the Earl of Arundel. During the Civil Wars the pictures were removed by his son to Antwerp, and there sold by auction.

Who can look down Buckingham Street in the twilight, and see the pediment of the old water gate of the duke’s house, without repeating to himself the scourging lines of Dryden when he drew Buckingham as Zimri?—

“A man so various that he seem’d to be

Not one but all mankind’s epitome;

Stiff in opinions, always in the wrong;

Was everything by turns, and nothing long;

But, in the course of one revolving moon,

Was chemist, fiddler, statesman, and buffoon.”[233]

In vain Settle eulogised the mercurial and licentious spendthrift. Settle’s verse is forgotten, but we all remember Pope’s ghastly but exaggerated picture of the rake’s death in “the worst inn’s worst room”—

“No wit to flatter left of all his store,

No fool to laugh at, which he valued more,

There, victor of his health, of fortune, friends,

And fame, this lord of useless thousand ends.”

[Pg 133]The first Duke of Buckingham, to judge by Clarendon, who was the friend of all friends of absolutism, must have been a man of magnificent generosity and “flowing courtesy,” a staunch friend, and a desperate and unrelenting hater; but he was an enemy of the people; and had he survived the knife of Felton he must have been the first of a faithless king’s bad counsellors to perish on the scaffold.

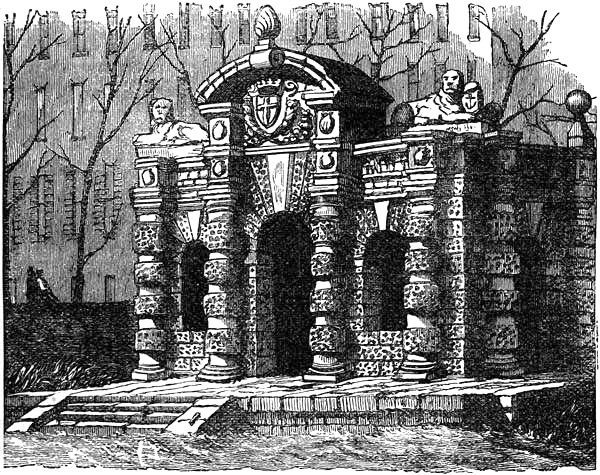

THE WATER GATE, 1860.

The second duke was a base-tempered, shameless profligate, a fickle, dishonest intriguer, who perished at last, a poor worn-out man, in a farmer’s house in Yorkshire, from a cold caught while hunting. He was the author of several obscene lampoons, from which Swift took some hints; and he was the godfather of a mock tragedy, The Rehearsal, in which he was helped by Martin Clifford and Butler, the author of Hudibras, the latter of whom he left to starve.[Pg 134] Baxter, it is true, drops a redeeming word or two on behalf of the gay scoundrel; but then Buckingham had intrigued with the Puritans.

York Stairs, the only monument of Zimri’s splendour left, stand now in the middle of the gardens of the new Embankment. Till the Embankment was made, the gate was approached by a small enclosed terrace planted with lime trees. The water gate consists of a central archway and two side windows. Four rusticated columns support an arched pediment and two couchant lions holding shields. On a scroll are the Villiers arms. On the street side rise three arches, flanked by pilasters and an entablature, on which are four stone globes. Above the keystone of the arches are shields and anchors. In the centre are the arms of Villiers impaling those of Manners. The Villiers’ motto, Fidei coticula crux, “The cross is the whetstone of faith,” is inscribed on the frieze. The gate, as it now stands, is ridiculous, and is almost buried in the soil. It would be a charity to remove it to a water-side position.

In 1661, on the day of the great affray at the Tower Wharf between the retinues of the French and Spanish ambassadors, arising out of a dispute for precedence, Pepys saw the latter return to York House in triumph, guarded with fifty drawn swords, having killed several Frenchmen. “It is strange,” says the amusing quidnunc, “to see how all the city did rejoice, and, indeed, we do naturally all love the Spanish and hate the French.” Worthy man! the fact was, all time-servers were then agog about the queen who was expected from Portugal. From York House Pepys went peering about the French ambassador’s, and found his retainers all like dead men and shaking their heads. “There are no men in the world,” he says, “of a more insolent spirit when they do well, and more abject if they miscarry, than these people are.”[234]

In 1683 the learned and amiable John Evelyn, being then on the Board of Trade, took a house in Villiers Street for the winter, partly for business purposes, partly to educate[Pg 135] his daughters.[235] Evelyn’s works gave a valuable impetus to art and agriculture.

Addison’s jovial friend, that delightful writer, Sir Richard Steele, lived in Villiers Street from 1721 to 1724, after the death of his wife, the jealous “Prue.” Here he wrote his Conscious Lovers. The big, swarthy-faced ex-trooper, so contrasting with his grave and colder friend Addison, is a salient personage in the English Temple of Fame.

Duke Street, built circa 1675,[236] was named from the last Duke of Buckingham. Humphrey Wanley, the great Harleian librarian, lived here, and the son of Shadwell, the poet and Dryden’s enemy, who was an eminent physician, and inherited much of his father’s excellent sense.

In 1672 the “chemyst, statesman, and buffoon” Duke of Buckingham sold York House and gardens for £30,000 to a brewer and woodmonger, who pulled it down and laid out the present streets, naming them, with due respect to rank and wealth, even in a rascal, George Street, Villiers Street, Duke Street, and Buckingham Street. In 1668 their rental was £1359: 10s.[237]

In Charles II.’s time waterworks were started at York Buildings by a company chartered to supply the West end with water, but they failed, being in advance of the time. The company, however, did not concentrate its energies on waterworks; it gave concerts, bought up forfeited estates in Scotland, and started many wild and eccentric projects, in some of which Steele figured prominently. The company has long been forgotten, though kept in memory by a tall water tower, which was standing in the reign of George III.

In Buckingham Street, built in 1675, Samuel Pepys, the diarist, came to live in 1684. The house, since rebuilt, was the last on the west side, and looked on the Thames. It had been his friend Hewer’s before him. A view of the library shows us the tall plain book-cases, and a central window looking on the river. Pepys, the son of an army[Pg 136] tailor, and as fond of dress and great people as might be expected of a tailor’s son, was for a long time Secretary of the Admiralty under Charles II. He was President of the Royal Society; and it is largely to his five folio books of ballads that we owe Dr. Percy’s useful compilation, The Relics of Ancient Poetry. Pepys died in 1703, at the house of his friend Hewer, at Clapham.

Pepys’s house (No. 14) became afterwards, in the summer of 1824, the home of Etty, the painter, and remained so till within a few months of his death in 1849. Etty first took the ground floor (afterwards occupied by Mr. Stanfield), then the top floor; the special object of his ambition being to watch sunsets over the river, which he loved as much as Turner did, who frequently said, “There is finer scenery on its banks than on those of any river in Italy.” Its ebb and flow, Etty used to declare, was like life, and “the view from Lambeth to the Abbey not unlike Venice.” In those river-side rooms the artists of two generations have assembled—Fuseli, Flaxman, Holland, Constable, and Hilton—then Turner, Maclise, Dyce, Herbert, and all the younger race. Etty’s rooms looked on to a terrace, with a small cottage at one end; the keeper once was a man named Hewson, supposed to be the original Strap of Roderick Random.[238] An amiable, dreamy genius was the son of the miller and gingerbread-maker of York.

The witty Earl of Dorset lived in this street in 1681.

Opposite Pepys’s house, and on the east side (left-hand corner), was a house where Peter the Great lodged when in England. Here, after rowing about the Thames, watching the boat-building, or pulling to Deptford and back, this brave half-savage used to return and spend his rough evenings with Lord Caermarthen, drinking a pint of hot brandy and pepper, after endless flasks of wine. It was certainly “brandy for heroes” in this case.

Lord Caermarthen was at this time Lord President of the Council, and had been appointed Peter’s cicerone by[Pg 137] King William. The Russian czar was a hard drinker, and on one occasion is said to have drunk a pint of brandy, a bottle of sherry, and eight flasks of sack, after which he calmly went to the play. While in York Buildings, the rough czar was so annoyed with the vulgar curiosity of intrusive citizens, that he would sometimes rise from his dinner and leave the room in a rage. Here the Quakers forced themselves upon him, and presented him with Barclay’s Apology, after which the czar attended their meeting in Gracechurch Street. He once asked them of what use they were in any kingdom, since they would not bear arms. On taking his farewell of King William, Peter drew a rough ruby, valued at £10,000, from his waistcoat pocket, and presented it to him screwed up in brown paper.[239] He went back just in time to crush the Strelitzes, imprison his sister Sophia, and wage war on Charles XII. The great reformer was only twenty-six years old when he visited England.

In 1706 Robert Harley, Esq., afterwards Swift’s great patron and Earl of Oxford, lived here;[240] and (1785) John Henderson, the actor, died in this street.

Walter, Lord Hungerford, of Farleigh Castle, Somerset, took the Duke of Orleans prisoner at Agincourt. He was Lord High Steward of Henry V. and one of the executors to his will, and Lord High Treasurer in the reign of Henry VI. This illustrious noble was the son of Sir Thomas de Hungerforde, who in 51 Edward III. was the first to take the chair as Speaker of the House of Commons.

Hungerford Market covered the site of the seat of the Hungerford family. Pepys mentions a fire at the house of old Lady Hungerford in Charles II.’s time.

Sir Edward (her husband), created a Knight of the Bath at the coronation of Charles II., pulled down the old mansion and divided it in 1680 into several houses, enclosing also a market-place. On the north side of the market-house was a bust of one of the family in a full-bottomed wig.[241] It grew a disused and ill-favoured place[Pg 138] before 1833. When a new market (Fowler, architect) was opened, it was intended to put an end to the monopoly of Billingsgate. The old market had at first answered well for fruit and vegetables, as there was no need of porters from the water side; but by 1720 Covent Garden had beaten it off.[242] It attempted too much in rivalling at once Leadenhall and Billingsgate, and failed—only a few fishmongers lingering on to the last.

In 1845 a suspension bridge, crossing from Hungerford to Lambeth (built under Mr. I. K. Brunel’s supervision), was opened. It consisted of three spans, and two brick towers in the Italian style; the main span, at the time of its erection, was larger than that of any other in the country, and only second to that of the bridge at Fribourg. It cost £110,000, and consumed more than 10,000 tons of iron.[243]

In the same year the bridge was sold to the original proprietors for £226,000, but the purchase was never carried out. It was replaced in 1864 by a railway bridge, and the market itself was filled up by an enormous railway station. The market had sunk to zero years before. In 1850 some rogue of a speculator had opened in it a pretended exhibition of the surplus articles rejected for want of room from the glass palace in Hyde Park. It proved a total failure, and swallowed up a vast sum of money and a fine northern estate or two. Latterly it had become a gratuitous music-hall, a billiard-room, and a penny-ice house, conducted by an Italian.

The railway station, built by Mr. Barry, the son of the architect of the New Houses of Parliament, faces the Strand. It is of a most creditable design, and the high Mansard roofs, which surmounted the hotel which forms its front, are of a freer and grander character than those of any modern London building. A model of the Eleanor Cross has been erected in the courtyard in front of it. This building is one of the first omens of better things that we have yet seen in our still terribly mean and ugly city.

[Pg 139]Craven Street was called Spur Alley till 1742.[244] Grinling Gibbons, the great wood-carver, born at Rotterdam, and whose genius John Evelyn discovered, lived here after leaving the Belle Sauvage Yard. Here he must have fashioned those fragile strings of birds and fruit and flowers that adorn so many city churches, and the houses of so many English noblemen. At No. 7, in 1775, lodged the great Benjamin Franklin, then no longer a poor printer, but the envoy of the American colonies. Here Lords Howe and Stanhope visited him to propose terms from Lords Camden and Chatham, but unfortunately only in vain.[245] That weak and unfortunate man, the Rev. Mr. Hackman, who shot Miss Ray, the actress and the mistress of Lord Sandwich, who had encouraged his suit, lived in this street.

James Smith, one of the authors of the Rejected Addresses,—a series of parodies rivalled only by those of Bon Gaultier, lived at No. 27. It was on his own street that he wrote the well-known epigram—[246]

“In Craven Street, Strand, the attorneys find place,

And ten dark coal barges are moor’d at its base.

Fly, Honesty, fly! seek some safer retreat:

There’s craft in the river and craft in the street.”

But Sir George Rose capped this in return, retorting in extemporaneous lines, written after dinner:—

“Why should Honesty fly to some safer retreat,

From attorneys and barges?—’od rot ’em!

For the lawyers are just at the top of the street,

And the barges are just at the bottom.”

James Smith, the intellectual hero of this street, the son of a solicitor to the Ordnance, was born in 1775. In 1802 he joined the staff of the Pic-Nic newspaper, with Combe, Croker, Cumberland, and that mediocre poet, Sir James Bland Burgess. It changed its name to the Cabinet, and died in 1803. From 1807 to 1817 James Smith [Pg 140]contributed to the Monthly Mirror his “Horace in London.” In 1812 came out the Rejected Addresses, inimitable parodies by himself and his brother, not merely of the manner but of the very mode of thought of Wordsworth, Cobbett, Southey, Coleridge, Crabbe, Lord Byron, Scott, etc. The copyright, originally offered to Mr. Murray for £20, but declined, was purchased by him in 1819, after the sixteenth edition, for £131; so much for the foresight of publishers. The book has since deservedly gone through endless editions, and has not been approached even by the talented parody writers of Punch. Those who wish to see the story of this publication in detail, must hunt it up in the edition of the Addresses illustrated by George Cruickshank.

Mr. Smith was the chief deviser of the substance of the Entertainments of the elder Charles Mathews. He wrote the Country Cousins in 1820, and in the two succeeding years the Trip to France and the Trip to America. For these last two works the author received a thousand pounds. “A thousand pounds!” he used to ejaculate, shrugging his shoulders, “and all for nonsense.”[247]

James Smith was just the man for Mathews, with his slight frameworks of stories filled up with songs, jokes, puns, wild farcical fancies, and merry conceits, and here and there among the motley, with true touches of wit, pathos, and comedy, and faithful traits of life and character, such as only a close observer of society and a sound thinker could pen.

He was lucky enough to obtain a legacy of £300 for a complimentary epigram on Mr. Strahan, the king’s printer. Being patted on the head when a boy by Chief-Justice Mansfield, in Highgate churchyard, and once seeing Horace Walpole on his lawn at Twickenham, were the two chief historical events of Mr. Smith’s quiet life. The four reasons that kept so clever a man employed on mere amateur trifling were these—an indolent disinclination to sustained work, a fear of failure, a dislike to risk a well-earned fame, and a foreboding that literary success might injure his practice as a lawyer. His favourite visits were to Lord Mulgrave’s,[Pg 141] Mr. Croker’s, Lord Abinger’s, Lady Blessington’s, and Lord Harrington’s.

Pretty Lady Blessington used to say of him, that “James Smith, if he had not been a witty man, must have been a great man.” He died in his house in Craven Street, with the calmness of a philosopher, on the 24th of December 1839, in the sixty-fifth year of his age.[248] Fond of society, witty without giving pain, a bachelor, and therefore glad to escape from a solitary home, James Smith seems to have been the model of a diner-out.

Caleb Whitefoord, a wine merchant in Craven Street, and an excellent connoisseur in old pictures, was one of the legacy-hunters who infested the studio of Nollekens, the miserly sculptor of Mortimer Street. He was a foppish dresser, and was remarkable for a dashing three-cornered hat, with a sparkling black button and a loop upon a rosette. He wore a wig with five tiers of curls, of the Garrick cut, and he was one of the last to wear such a monstrosity. This crafty wine merchant used to distribute privately the most whimsical of his Cross Readings, Ship News, and Mistakes of the Press—things in their day very popular, though now surpassed in every number of Punch. Some of the best were the following:—“Yesterday Dr. Pretyman preached at St. James’s,—and performed it with ease in less than sixteen minutes.” “Several changes are talked of at Court,—consisting of 9050 triple bob-majors.” “Dr. Solander will, by Her Majesty’s command, undertake a voyage—round the head-dress of the present month.” “Sunday night.—Many noble families were alarmed—by the constable of the ward, who apprehended them at cards.” A simple-hearted age could laugh heartily at these things: would that we could!

It has often been asserted that Goldsmith’s epitaph on Whitefoord was written by the wine merchant himself, and sent to the editor of the fifth edition of the Poems by a convenient common friend. It is not very pointed, and the length of the epitaph is certainly singular, considering[Pg 142] that the poet dismissed Burke and Reynolds in less than eighteen lines.

Adam built an octagon room in Whitefoord’s house in order to give his pictures an equal light; and Mr. Christie adopted the idea when he fitted up his large room in King Street, St. James’s.[249]

Goldsmith is said to have been intimate with witty, punning Caleb Whitefoord, and certain it is his name is found in the postscript to the poem of Retaliation, written by Oliver on some of his friends at the St. James’s Coffee-house. These were the Burkes, fretful Cumberland, Reynolds, Garrick, and Canon Douglas. In this poem Goldsmith laments that Whitefoord should have confined himself to newspaper essays, and contented himself with the praise of the printer of the Public Advertiser; he thus sums him up:—

“Rare compound of oddity, frolic, and fun,

Who relish’d a joke and rejoiced in a pun;

Whose temper was generous, open, sincere;

A stranger to flattery, a stranger to fear.

******

“Merry Whitefoord, farewell! for thy sake I admit

That a Scot may have humour—I’d almost said wit;

This debt to thy memory I cannot refuse,

Thou best-humour’d man with the worst-humour’d Muse.”

Whitefoord became Vice-President of the Society of Arts.

Anthony Pasquin (Williams), a celebrated art critic and satirist of Dr. Johnson’s time, was articled to Matt Darley, the famous caricaturist of the Strand, to learn engraving.[250]

The old name of Northumberland Street was Hartshorne Lane or Christopher Alley.[251] Here Ben Jonson lived when he was a child, and after his mother had taken a bricklayer for her second husband.

At the bottom of this lane Sir Edmondbury Godfrey had his wood wharf. This fact shows how much history is illustrated by topography, for the residence of the unfortunate[Pg 143] justice explains why it should have been supposed that he had been inveigled into Somerset House.

In 1829 Mr. Wood, who kept a coal wharf, resided in Sir Edmondbury’s old premises at the bottom of Northumberland Street. It was here the court justice’s wood-wharf was, but his house was in Green’s Lane, near Hungerford Market.[252] During the Great Plague Sir Edmondbury had been very active; on one occasion, when his men refused to act, he entered a pest-house alone to apprehend a wretch who had stolen at least a thousand winding-sheets. Four medals were struck on his death. There is also a portrait of the unlucky woodmonger in the waiting-room adjoining the Vestry of St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields.[253] He wore, it seems, a full black wig, like Charles II.

Three men were tried for his murder—the cushion-man at the Queen’s Chapel, the servant of the treasurer of the chapel, and the porter of Somerset House. The truculent Scroggs tried the accused, and those infamous men, Oates, Prance, and Bedloe, were the false witnesses who murdered them. The prisoners were all executed. Sir Edmondbury’s corpse was embalmed and borne to its funeral at St. Martin’s from Bridewell. The pall was supported by eight knights, all justices of the peace, and the aldermen of London followed the coffin. Twenty-two ministers marched before the body, and a great Protestant mob followed. Dr. William Lloyd preached the funeral sermon from the text 2 Sam. iii. 24. The preacher was guarded in the pulpit by two clergymen armed with “Protestant flails.”

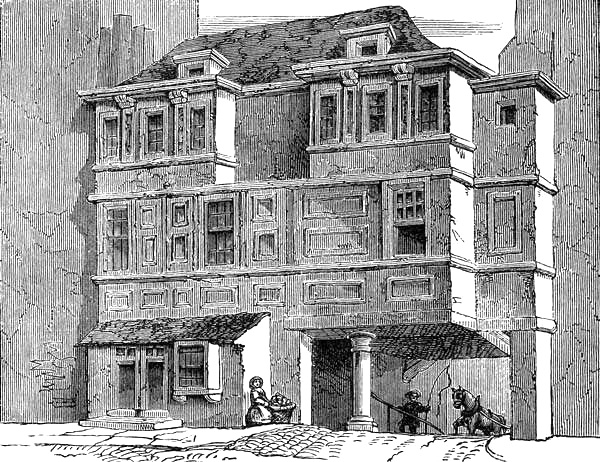

YORK STAIRS, WITH THE HOUSES OF PEPYS AND PETER THE GREAT, AFTER CANALETTI (CIRCA 1745).

In July 1861, No. 16 Northumberland Street, then an old-fashioned, dingy-looking house, with narrow windows, which had been divided into chambers, was the scene of a fight for life and death between Major Murray and Mr. Roberts, a solicitor and bill-discounter; the latter attempted the life of the former for the sake of getting possession of his mistress, to whom he had lent money. Under pretext of advancing a loan to the Grosvenor Hotel Company, of[Pg 144] which the major was a promoter, he decoyed him into a back room on the first floor of No. 16, then shot him in the back of the neck, and immediately after in the right temple. The major, feigning to be dead, waited till Roberts’s back was turned, then springing to his feet attacked him with a pair of tongs, which he broke to pieces over his assailant’s head. He then knocked him down with a bottle which lay near, and escaped through the window, and from thence by a water-pipe to the ground. Roberts died soon afterwards, but Major Murray recovered, and the jury returning a verdict of “Justifiable Homicide,” he was released. The papers described Roberts’s rooms as crowded with dusty Buhl cabinets, inlaid tables, statuettes, and drawings. These were smeared with blood and wine, while on the glass[Pg 145] shades of the ornaments a rain of blood seemed to have fallen.

The embankment, which here is very wide, and includes several acres of garden on the spot where the Thames once flowed, has largely altered the character of the streets below the Strand and the river, destroying the picturesque wharves and spoiling the appearance of the Water Gate, which is half buried in gravel and flowers, like the Sphynx in Egypt. Between it and the Thames now stands Cleopatra’s Needle, brought over to England at great cost of money and life, and set up here in 1878.

DURHAM HOUSE, 1790.

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:12:53 GMT