Haunted London, Index

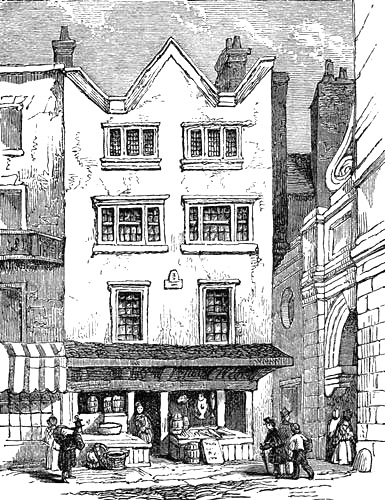

CROCKFORD’S FISH SHOP.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE NORTH SIDE OF THE STRAND, FROM TEMPLE BAR TO CHARING CROSS,

WITH DIGRESSIONS ON THE SOUTH.

The upper stratum of the Strand soil is composed of a reddish yellow earth, containing coprolites. Below this runs a seam of leaden-coloured clay, mixed with a few[Pg 147] martial pyrites, calcined-looking lumps of iron and sulphur with a bright silvery fracture.

A petition of the inhabitants of the vicinity of the King’s Palace at Westminster (8 Edward II.) represents the footway from Temple Bar to their neighbourhood as so bad that both rich and poor men received constant damage, especially in the rainy season, the footway being interrupted by bushes and thickets. A tax was accordingly levied for the purpose, and the mayor and sheriffs of London and the bailiff of Westminster were appointed overseers of the repairs.

In the 27th of Edward III. the Knights Templars were called upon to repair[254] “the bridge of the new Temple,” where the lords who attended Parliament took water on their way from the City. Workmen constructing a new sewer in the Strand, in 1802, discovered, eastward of St. Clement’s,[255] a small, one-arched stone bridge, supposed to be the one above alluded to, unless it was an arch thrown over some gully when the Strand was a mere bridle-road.

In James I.’s time, Middleton, the dramatist, describes a lawyer as embracing a young spendthrift, and urging him to riot and excess, telling him to make acquaintance with the Inns of Court gallants, and keep rank with those that spent most; to be lofty and liberal; to lodge in the Strand; in any case, to be remote from the handicraft scent of the City.[256]

It is but right to remind the reader that within the last few years the whole of that part of the north side of the Strand lying between Temple Bar and St. Clement’s Inn, including what was once known as Pickett Street, and extending backward almost as far as Lincoln’s Inn, has been demolished, in order to make room for the new Law Courts, which are now fast rising towards completion.

The house which immediately adjoined Temple Bar on[Pg 148] the north side, to the last a bookseller’s, stood on the site of a small pent-house of lath and plaster, occupied for many years by Crockford as a shell-fish shop. Here this man made a large sum of money, with which he established a gambling club, called by his name, on the west side of St. James’s Street. It was shut up at Crockford’s death in 1844, and, having passed through sundry phases, is now the Devonshire Club. Crockford would never alter his shop in his lifetime; but at his death the quaint pent-house and James I. gable[257] were removed, and a yellow brick front erected.

That great engraver, William Faithorne, after being taken prisoner as a Royalist at Basing in the Civil Wars, went to France, where he was patronised by the Abbé de Marolles. He returned about 1650, and set up a shop—where he sold Italian, Dutch, and English prints, and worked for booksellers—without Temple Bar, at the sign of the Ship, next the Drake and opposite the Palsgrave Head Tavern. He lived here till after 1680. Grief for his son’s misfortunes induced consumption, of which he died in 1691. Flatman wrote verses to his memory. Lady Paston is thought his chef d’œuvre.[258]

Ship Yard, now swept away, had been granted to Sir Christopher Hatton in 1571. Wilkinson gives a fine sketch of an old gable-ended house in Ship Yard, supposed to have been the residence of Elias Ashmole, the celebrated antiquarian. Here, probably, he stored his alchemic books and those treasures of the Tradescants which he gave to Oxford.

In 1813 sundry improvements projected by Alderman Pickett led to the removal of one of the greatest eye-sores in London—Butcher Row. This street of ragged lazar-houses extended in a line from Wych Street to Temple Bar. They were overhanging, drunken-looking, tottering tenements,[259] receptacles of filth, and invitations to the[Pg 149] cholera. In Dr. Johnson’s time they were mostly eating-houses.

This stack of buildings on the west side of Temple Bar was in the form of an acute-angled triangle; the eastern point, nearest the Bar, was formed latterly by a shoemaker’s and a fishmonger’s shop, with wide fronts; its western point being blunted by the intersection of St. Clement’s vestry-room and almshouse. On both sides of it resided bakers, dyers, smiths, combmakers, and tinplate-workers.

The decayed street had been a flesh-market since Queen Elizabeth’s time, when it flourished. A scalemaker’s, a fine-drawer’s, and Betty’s chophouse, were all to be found there.[260] The whole stack was built of wood, and was probably of about the age of Edward VI. The ceilings were low, traversed by huge unwrought beams, and dimly lit by small casement windows. The upper stories overhung the lower, according to the old London plan of widening the footway.

It was at Clifton’s Eating-house, in Butcher Row, in 1763, that that admirable gossip and useful parasite, Boswell, with a tremor of foolish horror, heard Dr. Johnson disputing with a petulant Irishman about the cause of negroes being black.

“Why, sir,” said Johnson, with judicial grandeur, “it has been accounted for in three ways—either by supposing that they were the posterity of Ham, who was cursed; or that God first created two kinds of men, one black and the other white; or that by the heat of the sun the skin is scorched, and so acquires a sooty hue. This matter has been much canvassed among naturalists, but has never been brought to any certain issue.”[261]

What the Irishman’s arguments were, Boswell of course forgot, but as his antagonist became warm and intemperate, Johnson rose and quietly walked away. When he had retired, the Irishman said—“He has a most ungainly figure, and an affectation of pomposity unworthy of a man of[Pg 150] genius.” (This very same evening Boswell and his deity first supped together at the Mitre.) It was here, many years later, that Johnson spent pleasant evenings with his old college friend Edwards,[262] whom he had not seen since the golden days of youth. Edwards, a good, dull, simple-hearted fellow, talked of their age. “Don’t let us discourage one another,” said Johnson, with quiet reproof. It was this same worthy fellow who amused Burke at the club by saying—“You are a philosopher, Dr. Johnson. I have tried in my time to be a philosopher too, but I don’t know how it was, cheerfulness was always breaking in.” This was a wise blunder, worthy of Goldsmith, the prince of wise blunderers.

It was in staggering home from the Bear and Harrow in Butcher Row, through Clare Market, that Lee, the poet, lay down or fell on a bulk, and was stifled in the snow (1692).

Nat Lee was the son of a Hertfordshire rector; a pupil of Dr. Busby, a coadjutor of Dryden, and an unsuccessful actor. He drank himself into Bedlam, where, says Oldys, he wrote a play in twenty-five acts.[263] Two of his maddest lines were—

“I’ve seen an unscrewed spider spin a thought

And walk away upon the wings of angels.”

The Duke of Buckingham, who brought Lee up to town,[264] neglected him, and his extreme poverty no doubt drove him faster to Moorfields. Poor fellow! he was only thirty-five when he died. He is described as stout,[265] handsome, and red faced. The Earl of Pembroke, whose daughter married a son of the brutal Judge Jefferies, was Lee’s chief patron. The poet, when visiting him at Wilton, drank so hard that the butler is said to have been afraid he would empty the cellar. Lee’s poetry, though noisy and ranting, is full of true poetic fire,[266] and in tenderness and passion the critics of his time compared him to Ovid and Otway.

[Pg 151]Thanks to the alderman, whose name is forgotten, though it well deserved to live,—the streets, lanes, and alleys which once blocked up St. Clement’s Church, like so many beggars crowding round a rich man’s door, were swept away, and the present oval railing erected. The enlightened Corporation at the same time built the big, dingy gateway of Clement’s Inn—people at the time called it “stupendous;”[267] and to it were added the restored vestry-room and almshouse. The south side of the Strand was also rebuilt, with loftier and more spacious shops. In the reign of Edward VI. this beginning of the Strand had been a mere loosely-built suburban street, the southern houses, then well inhabited, boasting large gardens.

There is a fatality attending some parts of London. In spite of Alderman Pickett and his stupendous arch of stucco, the new houses on the north side did not take well. They were found to be too large and expensive; they became under-let,[268] and began by degrees to relapse into their old Butcher Row squalor; the tide of humanity setting in towards Westminster flowing away from them to the left. As in some rivers the current, for no obvious reason, sometimes bends away to the one side, leaving on the other a broad bare reach of grey pebble, so the human tide in the Strand has always, in order to avoid the detour of the twin streets (Holywell and Wych), borne away to the left.

It is probable that Palsgrave Place, on the south side, just beyond Child’s bank, in Temple Bar without, marks the site of the Old Palsgrave’s Head Tavern. The Palsgrave was that German prince who was afterwards King of Bohemia, and who married the daughter of James I.

No. 217 Strand, on the south side, was Snow’s, the goldsmith. Gay has preserved his memory in some pleasant verses. It was, a few years ago, the bank of those most decent of defrauders, Strachan, Paul, and Bates, and through them proved the grave of many a fortune. Next[Pg 152] to it, westwards, is Messrs. Twinings bank, and their still more ancient tea shop.

The Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand (south side), afterwards the Whittington Club, and now the Temple Club, is described by Strype as a “large and curious house,” with good rooms and other conveniences for entertainments.[269] Here Dr. Johnson occasionally supped with Boswell, and bartered his wisdom for the flattering Scotchman’s inanity. In this same tavern the sultan of literature quarrelled with amiable but high-spirited Percy about old Dr. Mounsey; and here, when Sir Joshua Reynolds was gravely and calmly upholding the advantages of wine in stimulating and inspiring conversation, Johnson said, with good-natured irony, “I have heard none of these drunken—nay, drunken is a coarse word—none of these vinous flights!”[270]

St. Clement’s is one of Wren’s fifty churches, and it was built by Edward Pierce, under Wren’s superintendence.[271] It took the place of an old church mentioned by Stow, that had become old and ruinous, and was taken down circa 1682, during the epidemic for church-building after the Great Fire.

This church has many enemies and few friends. One of its bitterest haters calls it a “disgusting fabric,” obtruded dangerously and inconveniently upon the street. A second opponent describes the steeple as fantastic, the portico clumsy and heavy, and the whole pile poor and unmeaning. Even Leigh Hunt abuses it as “incongruous and ungainly.”[272]

There have been great antiquarian discussions as to why the church is called St. Clement’s “Danes.” Some think there was once a massacre of the Danes in this part of the road to Westminster; others declare that Harold Harefoot was buried in the old church; some assert that the Danes, driven out of London by Alfred, were allowed to settle between Thorney Island (Westminster) and Ludgate, and[Pg 153] built a church in the Strand; so, at least, we learn, Recorder Fleetwood told Treasurer Burleigh. The name of Saint Clement was taken from the patron saint of Pope Clement III., the friend of the Templars, who dwelt on the frontier line of the City.

In 1725 there was a great ferment in the parish of St. Clement’s, in consequence of an order from Dr. Gibson, Bishop of London, to remove at once an expensive new altar-piece painted by Kent, a fashionable architectural quack of that day; who, however, with “Capability Brown,” had helped to wean us from the taste for yew trees cut into shapes, Dutch canals, formal avenues, and geometric flower-beds.

Kent was originally a coach-painter in Yorkshire, and was patronised by the Queen, the Duke of Newcastle, and Lord Burlington. He helped to adorn Stowe, Holkham, and Houghton. He was at once architect, painter, and landscape gardener. In the altar-piece, the vile drawing of which even Hogarth found it hard to caricature, the painter was said to have introduced portraits of the Pretender’s wife and children. The “blue print,” published in 1725, was followed by another representing Kent painting Burlington Gate. The altar-piece was removed, but the nobility patronised Kent till he died, twenty years or so afterwards. We owe him, however, some gratitude, if, according to Walpole, he was the father of modern gardening.

The long-limbed picture caricatured by Hogarth was for some years one of the ornaments of the coffee-room of the Crown and Anchor in the Strand. Thence it was removed to the vestry-room of the church, over the old almshouses in the churchyard. After 1803 it was transported to the new vestry-room on the north side of the churchyard.[273]

In the old church Sir Robert Cecil, the first Earl of Salisbury, was baptized, 1563; as were Sir Charles Sedley, the delightful song-writer and the oracle of the licentious wits of his day, 1638-9; and the Earl of Shaftesbury, the[Pg 154] son of that troublous spirit “Little Sincerity,” and himself the author of the Characteristics.

The church holds some hallowed earth: in St. Clement’s was buried Sir John Roe, who was a friend of Ben Jonson, and died of the plague in the sturdy poet’s arms.

Dr. Donne’s wife, the daughter of Sir George More, and who died in childbed during her husband’s absence at the court of Henri Quatre, was buried here. Her tomb, by Nicholas Stone, was destroyed when the church was rebuilt. Donne, on his return, preached a sermon here on her death, taking the text—“Lo! I am the man that has seen affliction.” John Lowin, the great Shaksperean actor, lies here. He died in 1653. He acted in Ben Jonson’s “Sejanus” in 1605, with Burbage and Shakspere. Tradition reports him to have been the favourite Falstaff, Hamlet, and Henry VIII. of his day.[274] Burbage was the greatest of the Shaksperean tragedians, and Tarleton the drollest of the comedians; but Lowin must have been as versatile as Garrick if he could represent Hamlet’s vacillations, and also convey a sense of Falstaff’s unctuous humour. Poor mad Nat Lee, who died on a bulk in Clare Market close by, was buried at St. Clement’s, 1692; and here also lies poor beggared Otway, who died in 1685. In the same year as Lee, Mountfort, the actor, whom Captain Hill stabbed in a fit of jealousy in Howard Street adjoining, was interred here.

In 1713 Thomas Rymer, the historiographer of William III. and the compiler of the Fœdera and fifty-eight manuscript volumes now in the British Museum, was interred here. He had lived in Arundel Street. In 1729 James Spiller, the comedian of Hogarth’s time, was buried at St. Clement’s. A butcher in Clare Market wrote his epitaph, which was never used. Spiller was the original Mat of the Mint in the “Beggars’ Opera.” His portrait, by Laguerre, was the sign of a public-house in Clare Market.[275]

In this church was probably buried, at the time of the[Pg 155] Plague, Thomas Simon, Cromwell’s celebrated medallist. His name, however, is not on the register.[276]

Mr. Needham, who was buried at St. Clement’s with far better men, was an attorney’s clerk in Gray’s Inn, who, in 1643, commenced a weekly paper. He seems to have been a mischievous, unprincipled hireling, always ready to sell his pen to the best bidder.

It is not for us in these later days to praise a church of the Corinthian order, even though its southern portico be crowned by a dome and propped up with Ionic pillars. Its steeple of the three orders, in spite of its vases and pilasters, does not move me; nor can I, as writers thought it necessary to do thirty years ago,[277] waste a churchwarden’s unreasoning admiration on the wooden cherubim, palm-branches, and shields of the chancel; nor can even the veneered pulpit and cumbrous galleries, or the Tuscan carved wainscot of the altar draw any praise from my reluctant lips.

The arms of the Dukes of Norfolk and the Earls of Arundel and Salisbury, in the south gallery, are worthy of notice, because they show that these noblemen were once inhabitants of the parish.

Among the eminent rectors of St. Clement’s was Dr. George Berkeley, son of the Platonist bishop, the friend of Swift, to whom Pope attributed “every virtue under heaven.” He died in 1798. It was of his father that Atterbury said, he did not think that so much knowledge and so much humility existed in any but the angels and Berkeley.[278]

Dr. Johnson, the great and good, often attended service at St. Clement’s Church. They still point out his seat in the north gallery, near the pulpit. On Good Friday, 1773, Boswell tells us he breakfasted with his tremendous friend (Dr. Levett making tea), and was then taken to church by him. “Dr. Johnson’s behaviour,” he says, “was solemnly devout. I never shall forget the tremulous earnestness with[Pg 156] which he pronounced the awful petition in the Litany, ‘In the hour of death and in the day of judgment, good Lord, deliver us.’”[279]

Eleven years later the doctor writes to Mrs. Thrale, “after a confinement of 129 days, more than the third part of a year, and no inconsiderable part of human life, I this day returned thanks to God in St. Clement’s Church for my recovery—a recovery, in my 75th year, from a distemper which few in the vigour of youth are known to surmount.”

Clement’s Inn (of Chancery), a vassal of the Inner Temple, derives its name from the neighbouring church, and the “fair fountain called Clement’s Well,”[280] the Holy Well of the neighbouring street pump.

Over the gate is graven in stone an anchor without a stock and a capital C couchant upon it.[281] This device has reference to the martyrdom of the guardian saint of the inn, who was tied to an anchor and thrown into the sea by order of the emperor Trajan. Dugdale states that there was an inn here in the reign of Edward II.

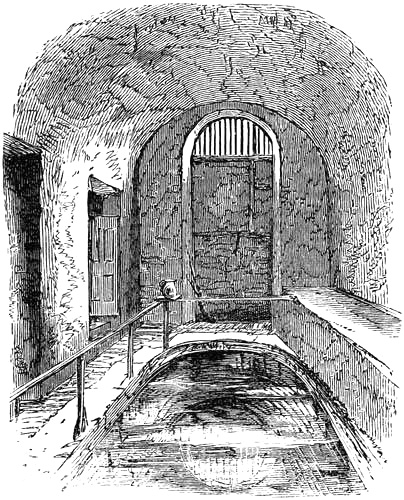

There is, indeed, a tradition among antiquaries, that as far back as the Saxon kings there was an inn here for the reception of penitents who came to the Holy Well of St. Clement’s; that a religious house was first established, and finally a church. The Holy Lamb, an inn at the west end of the lane, was perhaps the old Pilgrims’ Inn. In the Tudor times the Clare family, who had a mansion in Clare Market, appears to have occupied the site. From their hands it reverted to the lawyers. As for the well, a pump now enshrines it, and a low dirty street leads up to it. This is mentioned in Henry II.’s time[282] as one of the excellent springs at a small distance from London, whose waters are “sweet, healthful, and clear, and whose runnels murmur over the shining pebbles: they are much [Pg 157]frequented,” says the friend of Archbishop Becket, “both by the scholars from the school (Westminster) and the youth from the City, when on a summer’s evening they are disposed to take an airing.” It was seven centuries ago that the hooded boys used to play round this spring, and at this very moment their descendants are drinking from the ladle or splashing each other with the water, as they fill their great brown pitchers. The spring still feeds the Roman Bath in the Strand already mentioned.

“For men may come, and men may go,

But I flow on for ever.”[283]

The hall of St. Clement’s Inn is situated on the south side of a neat small quadrangle. It is a small Tuscan building, with a large florid Corinthian door and arched windows, and was built in 1715. In the second irregular area there is a garden, with a statue of a kneeling black figure supporting a sun-dial on the east side.[284] It was given to the inn by an Earl of Clare, but when is unknown. It was brought from Italy, and is said to be of bronze, but ingenious persons having determined on making it a blackamoor, it has been painted black. A stupid, ill-rhymed, cumbrous old epigram sneers at the sable son of woe flying from cannibals and seeking mercy in a lawyers’ inn. The first would not have eaten him till they had slain him; but lawyers, it is well known, will eat any man alive.[285]

Poor Hollar, the great German engraver, lived in 1661 just outside the back door of St. Clement’s, “as soon as you come off the steps, and out of that house and dore at your left hand, two payre of stairs, into a little passage right before you.” He was known for “reasons’ sake” to the people of the house only as “the Frenchman limner.” Such was the direction he sent to that gossiping Wiltshire gentleman, John Aubrey.

The inn has very probably reared up a great many[Pg 158] clever men; but it is chiefly renowned for having fostered that inimitable old bragging twaddler and country magistrate, the immortal Justice Shallow. Those chimes that “in a ghostly way by moonlight still bungle through Handel’s psalm tunes, hoarse with age and long vigils”[286] as they are, must surely be the same that Shallow heard. How deliciously the old fellow vapours about his wild times!

“Ha, Cousin Silence, that thou hadst seen that that this knight and I have seen!—Ha, Sir John, said I well?”

Falstaff—“We have heard the chimes at midnight, Master Shallow.”

Shal.—“That we have, that we have, that we have; in faith, Sir John, we have; our watchword was—Hem, boys!—Come, let’s to dinner; come, let’s to dinner. Oh, the days that we have seen!—Come, come.”[287]

And before that, how he glories in the impossibility of being detected after bragging fifty-five years! This man, as Falstaff says, “lean as a man cut after supper out of a cheese-paring,” was once mad Shallow, lusty Shallow, as Cousin Silence, his toady, reminds him.

“By the mass,” says again the old country gentleman, “I was called anything, and I would have done anything, indeed, and roundly too. There was I and little John Doit of Staffordshire, and black George Barnes of Staffordshire, and Francis Pickbone, and Will Squele, a Cotswold man: you had not four such swinge-bucklers in all the inns of court again.”

And thus he goes maundering on with dull vivacity about how he played Sir Dagonet in Arthur’s Show at Mile End, and once remained all night revelling in a windmill in St. George’s Fields.

A curious record of Shakspere’s times serves admirably to illustrate Shallow’s boast. In Elizabeth’s time the eastern end of the Strand was the scene of frequent disturbances occasioned by the riotous and unruly students of the inns of court, who paraded the streets at night to[Pg 159] the danger of peaceable passengers. One night in 1582, the Recorder himself, with six of the honest inhabitants, stood by St. Clement’s Church to see the lanterns hung out, and to try and meet some of the brawlers, the Shallows of that time. About seven at night they saw young Mr. Robert Cecil, the Treasurer’s son, pass by the church and salute them civilly, on which they said, “Lo, you may see how a nobleman’s son can use himself, and how he pulleth off his cap to poor men—our Lord bless him!” Upon which the Recorder wrote to his father, like a true courtier, making capital of everything, and said, “Your lordship hath cause to thank God for so virtuous a child.”

Through the gateway in Pickett Street, a narrow street led to New Court, where stood the Independent Meeting House in which the witty Daniel Burgess once preached. The celebrated Lord Bolingbroke was his pupil, and the Earl of Orrery his patron. He died 1712, after being much ridiculed by Swift and Steele for his sermon of The Golden Snuffers, and for his pulpit puns in the manner followed by Rowland Hill and Whitfield. This chapel was gutted during the Sacheverell riots, and repaired by the Government. Two examples of Burgess’s grotesque style will suffice. On one occasion, when he had taken his text from Job, and discoursed on the “Robe of Righteousness,” he said—

“If any of you would have a good and cheap suit, you will go to Monmouth Street; if you want a suit for life, you will go to the Court of Chancery; but if you wish for a suit that will last to eternity, you must go to the Lord Jesus Christ and put on His robe of righteousness.”[288] On another occasion, in the reign of King William, he assigned as a motive for the descendants of Jacob being called Israelites, that God did not choose that His people should be called Jacobites.

Daniel Burgess was succeeded in his chapel by Winter and Bradbury, both celebrated Nonconformists. The latter of these was also a comic preacher, or rather a “buffoon,”[Pg 160] as one of Dr. Doddridge’s correspondents called him. It was said of his sermons that he seemed to consider the Bible to be written only to prove the right of William III. to the throne. He used to deride Dr. Watts’s hymns from the pulpit, and when he gave them out always said—

“Let us sing one of Watts’s whims.”

Bat Pidgeon, the celebrated barber of Addison’s time, lived nearly opposite Norfolk Street. His house bore the sign of the Three Pigeons. This was the corner house of St. Clement’s churchyard, and there Bat, in 1740, cut the boyish locks of Pennant[289]. In those days of wigs there were very few hair-cutters in London.

The father of Miss Ray, the singer, and mistress of old Lord Sandwich, is said to have been a well-known staymaker in Holywell Street, now Booksellers’ Row. His daughter was apprenticed in Clerkenwell, from whence the musical lord took her to load her with a splendid shame. On the day she went to sing at Covent Garden in “Love in a Village,” Hackman, who had left the army for the church, waited for her carriage at the Cannon Coffee-house in Cockspur Street. At the door of the theatre, by the side of the Bedford Coffee-house, Hackman rushed out, and as Miss Ray was being handed from her carriage he shot her through the head, and then attempted his own life[290]. Hackman was hanged at Tyburn, and he died declaring that shooting Miss Ray was the result of a sudden burst of frenzy, for he had planned only suicide in her presence.

The Strand Maypole stood on the site of the present church of St. Mary le Strand, or a little northward towards Maypole Alley, behind the Olympic Theatre. In the thirteenth century a cross had stood on this spot, and there the itinerant justices had sat to administer justice outside the walls. A Maypole stood here as early as 1634[291]. Tradition says it was set up by John Clarges, the Drury Lane blacksmith, and father of General Monk’s vulgar wife.

[Pg 161]The Maypole was Satan’s flag-staff in the eyes of the stern Puritans, who dreaded Christmas pies, cards, and dances. Down it came when Cromwell went up. The Strand Maypole was reared again with exulting ceremony the first May day after the Restoration. The parishioners bought a pole 134 feet high, and the Duke of York, the Lord High Admiral, lent them twelve seamen to help to raise it. It was brought from Scotland Yard with drums, music, and the shouts of the multitude; flags flying, and three men bare-headed carrying crowns.[292] The two halves being joined together with iron bands, and the gilt crown and vane and king’s arms placed on the top, it was raised in about four hours by means of tackle and pulleys. The Strand rang with the people’s shouts, for to them the Maypole was an emblem of the good old times. Then there was a morris dance, with tabor and pipe, the dancers wearing purple scarfs and “half-shirts.” The children laughed, and the old people clapped their hands, for there was not a taller Maypole in Europe. From its summit floated a royal purple streamer; and half way down was a sort of cross-trees or balcony adorned with four crowns and the king’s arms. It bore also a garland of vari-coloured favours, and beneath three great lanterns in honour of the three admirals and all seamen, to give light in dark nights. On this spot, a year before, the butchers of Clare Market had rung a peal with their knives as they burnt an emblematical Rump.[293]

In the year 1677 a fatal duel was fought under the Maypole, which had been snapped by a tempest in 1672.[294] One daybreak Mr. Robert Percival, a notorious duellist, only nineteen years of age, was found dead under the Maypole, with a deep wound in his left breast. His drawn and bloody sword lay beside him. His antagonist was never discovered, though great rewards were offered. The only clue was a hat with a bunch of ribbons in it, suspected to belong to the celebrated Beau Fielding, but it was never[Pg 162] traced home to him. The elder brother, Sir Philip Percival, long after, violently attacked a total stranger whom he met in the streets of Dublin. The spectators parted them. Sir Philip could account for his conduct only by saying he felt urged on by an irresistible conviction that the man he struck at was his brother’s murderer.[295]

The Maypole, disused and decaying, was pulled down in 1713, when a new one, adorned with two gilt balls and a vane, was erected in its stead. In 1718 the pole, being found in the way of the new church, was given to Sir Isaac Newton as a stand for a large French telescope that belonged to his friend Mr. Pound, the rector of Wanstead.

Saint Mary-le-Strand was begun in 1714, and consecrated in 1723-4.[296] It was one of the fifty ordered to be built in Queen Anne’s reign. The old church, pulled down by that Ahab, the Protector Somerset, to make room for his ill-omened new palace, stood considerably nearer to the river.

Gibbs, the shrewd Aberdeen architect, who succeeded to Wren and Vanbrugh, and became famous by building St. Martin’s Church, reared also St. Mary’s. Gibbs, according to Walpole, was a mere plodding mechanic. He certainly wanted originality, simplicity, and grace. St. Mary’s is broken up by unmeaning ornament; the pagoda-like steeple is too high,[297] and crushes the church, instead of as it were blossoming from it. One critic (Mr. Malton) alone is found to call St. Mary’s pleasant and picturesque; but I confess to having looked on it so long that I begin almost to forget its ugliness.

Gibbs himself tells us how he set to work upon this church. It was his first commission after his return from Rome. As the site was a very public one, he was desired to spare no cost in the ornamentation, so he framed it of two orders, making the lower walls (but for the absurd niches to hold nothing) solid, so as to keep out the noises of the[Pg 163] street. There was at first no steeple intended, only a small western campanile, or bell-turret; but, eighty feet from the west front, there was to be erected a column 250 feet high, crowned by a statue of Queen Anne. This absurdity was forgotten at the death of that rather insipid queen, and the stone still lying there, the thrifty parish authorities, unwilling to waste the materials, resolved to build a steeple. The church being already twenty feet from the ground, it was necessary to spread it north and south, and so the church, originally square, became oblong.

Pope calls St. Mary’s Church bitterly the church that—

Collects “the saints of Drury Lane.”[298]

Addison describes his Tory fox-hunter’s horror on seeing a church apparently being demolished, and his agreeable surprise when he found it was really a church being built.[299]

St. Mary’s was the scene of a tragedy during the proclamation of the short peace in 1802. Just as the heralds came abreast of Somerset House, a man on the roof of the church pressed forward too strongly against one of the stone urns, which gave way and fell into the street, striking down three persons: one of these died on the spot; the second, on his way to the hospital; and the third, two days afterwards. A young woman and several others were also seriously injured. The urn, which weighed two hundred pounds, carried away part of the cornice, broke a flag-stone below, and buried itself a foot deep in the earth. The unhappy cause of this mischief fell back on the roof and fainted when he saw the urn fall. He was discharged, no blame being attached to him. It was found that the urn had been fastened by a wooden spike, instead of being clamped with iron.[300]

The church has been lately refitted in an ecclesiastical style, and filled with painted windows. There are no galleries in its interior. The ceiling is encrusted with ornament. It contains a tablet to the memory of James[Pg 164] Bindley, who died in 1818. He was the father of the Society of Antiquaries, and was a great collector of books, prints, and medals.

New Inn, in Wych Street, is an inn of Chancery, appertaining to the Middle Temple. It was originally a public inn, bearing the sign of Our Lady the Virgin, and was bought by Sir John Fineux, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, in the reign of King Edward IV., to place therein the students of the law then lodged in St. George’s Inn, in the little Old Bailey, which was reputed to have been the most ancient of all the inns of Chancery.[301]

Sir Thomas More, the luckless minister of Henry VIII., was a member of this inn till he removed to Lincoln’s Inn. When the Great Seal was taken from this wise man, he talked of descending to “New Inn fare, wherewith many an honest man is well contented.”[302] Addison makes the second best man of his band of friends (after Sir Roger de Coverley) a bachelor Templar; an excellent critic, with whom the time of the play is an hour of business. “Exactly at five he passes through New Inn, crosses through Russell Court, and takes a turn at Wills’s till the play begins. He has his shoes rubbed and his periwig powdered at the barber’s as you go into the Rose.”[303]

Wych Street derives its name from the old name for Drury Lane—via de Aldewych. Till some recent improvements were effected in its tenants, it bore an infamous character, and was one of the disgraces of London.

The Olympic Theatre, in Wych Street, was built in 1805 by Philip Astley, a light horseman, who founded the first amphitheatre in London on the garden ground of old Craven House. It was opened September 18, 1806, as the Olympic Pavilion, and burnt to the ground March 29, 1849. It was built out of the timbers of the captured French man-of-war, La Ville de Paris, in which William IV. went out as midshipman. The masts of the vessel formed the flies,[Pg 165] and were seen still standing amidst the fire after the roof fell in. In 1813 it was leased by Elliston, and called the Little Drury Lane Theatre. Its great days were under the rule of Madame Vestris,[304] who, both as a singer and an actress, contributed to its success. More recently it was under the able and successful management of the late Mr. Frederick Robson. Born at Margate in 1821, he was early in life apprenticed to a copperplate engraver in Bedfordbury. He appeared first, unsuccessfully, at a private theatre in Catherine Street, and played at the Grecian Saloon as a comic singer and low comedian from 1846 to 1849. In 1853 he joined Mr. Farren at the Olympic. He there acquired a great reputation in various pieces—“The Yellow Dwarf,” “To oblige Benson,” “The Lottery Ticket,” and “The Wandering Minstrel,”—the last being an old farce originally written to ridicule the vagaries of Mr. Cochrane.

Lyon’s Inn, an inn of Chancery belonging to the Inner Temple, was originally a hostelry with the sign of the Lion. It was purchased by gentlemen students in Henry VIII.’s time, and converted into an inn of Chancery.[305]

It degenerated into a haunt of bill-discounters and Bohemians of all kinds, good and bad, clever and rascally, and remained a dim, mouldy place till 1861, when it was pulled down. Its site is now occupied by the Globe Theatre. Just before the demolition of the inn, when I visited it, a washerwoman was hanging out wet and flopping clothes on the site of Mr. William Weare’s chambers.

On Friday, 24th of October 1823, Mr. William Weare, of No. 2 Lyon’s Inn, was murdered in Gill’s Hill Lane, Hertfordshire, between Edgware and St. Alban’s. His murderer was Mr. John Thurtell, son of the Mayor of Norwich, and a well-known gambler, betting man, and colleague of prize-fighters. Under pretence of driving him down for a shooting excursion, Thurtell shot Weare with a pistol, and when he leaped out of the chaise, pursued him[Pg 166] and cut his throat. He then sank the body in a pond in the garden of his friend and probable accomplice, Probert, a spirit merchant, and afterwards removed it to a slough on the St. Alban’s road. His confederate, Hunt, a public singer, turned king’s evidence, and was transported for life. Thurtell was hanged at Hertford. He pleaded that Weare had robbed him of £300 with false cards at Blind Hookey, and he had sworn revenge; but it appeared that he had planned several other murders, and all for money. Probert was afterwards hanged in Gloucestershire for horse-stealing.

At the sale of the building materials some Jews were observed to be very eager to acquire the figure of the lion that adorned one of the walls. There were various causes assigned for this eagerness. Some said that a Jew named Lyons had originally founded the inn; others declared that the lion was considered to be an emblem of the Lion of the tribe of Judah. Directly the auctioneer knocked it down the Jewish purchaser drew a knife, mounted the ladder, and struck his weapon into the lion. “S’help me, Bob!” said he, in a tone of disgust, “if they didn’t tell me it was lead, and it’s only stone arter all!”

Gay, who speaks of the dangers of “mazy Drury Lane,” gives Catherine Street a very bad character. He describes the courtesans, with their new-scoured manteaus and riding-hoods or muffled pinners, standing near the tavern doors, or carrying empty bandboxes, and feigning errands to the Change.[306] The street is now almost entirely occupied by newspaper publishers. The Morning Herald, the Court Journal, the Naval and Military Gazette, the Gardener’s Gazette, the Builder, the Weekly Register, and the Court Gazette, all either are or have been published in Catherine Street. Scott’s Sanspareil Theatre was opened here about 1810 for the performance of operettas, dancing, and pantomimes.[307] In September 1741 a man named James Hall was executed at the end of Catherine Street.

The Maypole close to St. Mary’s Church is said to have been the first place in London where hackney coaches[Pg 167] were allowed to stand. Coaches were first introduced into England from Hungary in 1580 by Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel; but for a time they were thought effeminate. The Thames watermen especially railed against them, as might be expected. In the year 1634, a Captain Baily who had accompanied Raleigh in his famous expedition to Guiana, started four hackney coaches, with drivers in liveries, at the Maypole; but as, in the year 1613, sixty hackney coaches from London[308] plied at Stourbridge fair, perhaps there had been coach-stands in the streets before Baily’s time. In 1625 there were only twenty coaches in London; in 1666, under Charles II., the number had so increased that the king issued a proclamation complaining of the coaches blocking up the narrow streets and breaking up the pavement, and forbade coach-stands altogether.

Peter Molyn Tempest, the engraver of “The Cries of London,” published at the end of King William’s reign, lived in the Strand opposite Somerset House. “The Cries” were designed by Marcellus Laroon, a Dutch painter (1653-1702), who painted draperies for Kneller.[309] He was celebrated for his conversation pieces and his knack of imitating the old masters. Tempest’s quaint advertisement of the “Cries” in the London Gazette, May 28 and 31, 1688, runs thus:—

“There is now published the Cryes and Habits of London, lately drawn after the life in great variety of actions, curiously engraved upon fifty copper-plates, fit for the ingenious and lovers of art. Printed and sold by P. Tempest, over against Somerset House, in the Strand.”

The Morning Chronicle, whose office was opposite Somerset House, was started in 1770. It was to Perry, of the Morning Chronicle, that Coleridge, when penniless and about to enlist in a cavalry regiment, sent a poem and a request for a guinea, which he got. Hazlitt was theatrical critic to this paper, succeeding Lord Campbell in the post. In 1810 David Ricardo began his letters on the depreciation[Pg 168] of the currency in the Chronicle. James Perry, whose career we have no room to follow, lived in great style at Tavistock House, the house afterwards occupied for many years by Mr. Charles Dickens. The Sketches by Boz of Charles Dickens first appeared in the columns of the Chronicle. The last Morning Chronicle appeared on Wednesday, March 19, 1862. Latterly the paper was said to have been in the pay of the Emperor of France.

No. 346, at the east corner of Wellington Street, now the office of the Law Times, the Queen, and the Field, was Doyley’s celebrated warehouse for woollen articles. Dryden, in his Kind Keeper, speaks of “Doyley” petticoats; Steele, in his Guardian,[310] of his “Doyley” suit; while Gay, in the Trivia, describes a “Doyley” as a poor defence against the cold.

Doyley’s warehouse stood on the ancient site of Wimbledon House, built by Sir Edward Cecil, son to the first Earl of Exeter, and created Viscount Wimbledon by Charles I. The house was burnt to the ground in 1628, and the day before the viscount had had part of his house at Wimbledon accidentally blown up by gunpowder. Pennant, when a boy, was brought by his mother to a large glass shop, a little beyond Wimbledon House; the old man who kept it remembered Nell Gwynne coming to the shop when he was an apprentice; her footman, a country lad, got fighting in the street with some men who had abused his mistress.[311]

Mr. Doyley was a much respected warehouseman of Dr. Johnson’s time, whose family had resided in their great old house, next to Hodsall the banker’s, at the corner of Wellington Street, ever since Queen Anne’s time. The dessert napkins called Doyleys derived their name from this firm. Mr. Doyley’s house was built by Inigo Jones, and forms a prominent feature in old engravings of the Strand, as it had a covered entrance that ran out like a promontory into the carriage-way. It was pulled down about 1782.[312] Mr. Doyley, a man of humour and a friend of Garrick and[Pg 169] Sterne, was a frequenter of the Precinct Club, held at the Turk’s Head, opposite his own house. The rector of St. Mary’s attended the same club, and enjoyed the seat of honour next the fire.

THE OLD ROMAN BATH, STRAND.

Not far from this stood the Strand Bridge, which crossed the street, and received the streams flowing from the higher grounds down Catharine Street to the Thames. Strand Lane, hard by on the south, famous still for its old Roman bath, passed under the arch, and led to a water stair or landing pier. Addison, in his bright pleasant way, describes landing there one morning with ten sail of apricot boats, after having put in at Nine Elms for melons, consigned by Mr. Cuffe of that place to Sarah Sewell and Company at their stall in Covent Garden.[313]

[Pg 170]The Morning Post, whose office is in Wellington Street, was started in 1772; when almost defunct it was bought in 1796 by Daniel Stuart, and Christie the auctioneer, who gave only £600 for copyright, house, and plant. Coleridge, Southey, Lamb, Wordsworth, and Mackintosh all wrote for Stuart’s paper. Coleridge commenced his political papers in 1797, and on his return from Germany (November 1799) joined the badly-paid staff, but refused to become a parliamentary reporter. Fox declared in the House of Commons that Coleridge’s essays had led to the rupture of the peace of Amiens, an announcement which led to a pursuit by a French frigate, when the poet left Rome, where he then was, and sailed from Leghorn. Lamb wrote facetious paragraphs at sixpence a-piece.[314] The Morning Post soon became second only to the Chronicle, and the great paper for booksellers’ advertisements. It is mentioned by Byron as the organ of the aristocracy and of West End society, and it has maintained that position to the present time with little change.

The Athenæum, whose office is in Wellington Street, is identified with the name of Mr. (afterwards) Sir C. Wentworth Dilke. He was born in 1789, and was originally in the Navy Pay Office. He bought the paper, which had been unsuccessful since 1828 under its originator, that shifty adventurer, Mr. J. S. Buckingham, and also under Mr. John Sterling. Under his care it gradually grew into a sound property, and became what it now is, the Times of weekly papers. Its editor, Mr. Hervey, the author of many well-known poems, was replaced in 1853 by Mr. Hepworth Dixon, under whom it steadily throve, till his retirement in 1871.

A little farther up the street is the office of All the Year Round, a weekly periodical which, in 1859, took the place of Household Words, started by Mr. Charles Dickens in 1850. It contains essays by the best writers of the day, graphic descriptions of current events, and continuous stories. Mrs. Gaskell, Mr. Wilkie Collins, Charles Reade,[Pg 171] Lord Lytton, Mr. Sala, and Mr. Dickens himself, are among those who have published novels in its pages.

The original Lyceum was built in 1765 as an exhibition-room for the Society of Arts, by Mr. James Payne, an architect, on ground once belonging to Exeter House. The society splitting, and the Royal Academy being founded at Somerset House in 1768, the Lyceum Society became insolvent. Mr. Lingham, a breeches-maker, then purchased the room, and let it out to Flockton for his Puppet-show and other amusements. About 1794 Dr. Arnold partly rebuilt it as a theatre, but could not obtain a licence through the opposition of the winter houses.[315] It was next door to the shop of Millar the publisher.

The Lyceum in 1789-94 was the arena of all experimenters—of Charles Dibdin and his “Sans Souci,” of the ex-soldier Astley’s feats of horsemanship, of Cartwright’s “Musical Glasses,” of Philipstal’s successful “Phantasmagoria.” Lonsdale’s “Egyptiana” (paintings of Egyptian scenes, by Porter, Mulready, Pugh, and Cristall), with a lecture, was a failure. Here Ker Porter exhibited his large pictures of Lodi, Acre, and the siege of Seringapatam. Then came Palmer with his “Portraits,” Collins with his “Evening Brush,” Incledon with his “Voyage to India,” Bologna with his “Phantascopia,” and Lloyd with his “Astronomical Exhibition.” Subscription concerts, amateur theatricals, debating societies, and schools of defence were also tried here. One day it was a Roman Catholic chapel; next day the “Panther Mare and Colt,” the “White Negro Girl,” or the “Porcupine Man” held their levee of dupes and gapers in its changeful rooms.[316]

In 1809 Dr. Arnold’s son obtained a licence for an English opera-house. Shortly afterwards the Drury Lane company commenced performing here, their own theatre having been burnt. Mr. T. Sheridan was then manager. In 1815 Mr. Arnold erected the predecessor of the present theatre, on an enlarged scale, at an expense of nearly £80,000, and it was opened in 1816. In 1817 the [Pg 172]experiment of two short performances on the same evening was unsuccessfully tried. On April 1, 1818, Mr. Mathews, the great comedian, began here his entertainment called “Mail-coach Adventures,” which ran forty nights.

The Beef-steak Club was established in the reign of Queen Anne (before 1709).[317] The Spectator mentions it, 1710-11. The club met in a noble room at the top of Covent Garden Theatre, and never partook of any dish but beef-steaks. Their Providore was their president and wore their badge, a small gold gridiron, hung round his neck by a green silk riband.[318] Estcourt had been a tavern-keeper, and is mentioned in a poem of Parnell’s, who was himself too fond of wine. He died in 1712. Steele gives a delightful sketch of him. He had an excellent judgment, he was a great mimic, and he told an anecdote perfectly well. His well-turned compliments were as fine as his smart repartees. “It is to Estcourt’s exquisite talent more than to philosophy,” says Steele, “that I owe the fact that my person is very little of my care, and it is indifferent to me what is said of my shape, my air, my manner, my speech, or my address. It is to poor Estcourt I chiefly owe that I am arrived at the happiness of thinking nothing a diminution of myself but what argues a depravity of my will.”

The kindly essay ends beautifully. “None of those,” says the true-hearted man, “will read this without giving him some sorrow for their abundant mirth, and one gush of tears for so many bursts of laughter. I wish it were any honour to the pleasant creature’s memory that my eyes are too much suffused to let me go on.”

Later, Churchill and Wilkes, those partners in dissoluteness and satire, were members of this social club. After Estcourt, that jolly companion, Beard the singer, became president of this jovial and agreeable company.

It was an old custom at theatres to have a Beef-steak Club that met every Saturday, and to which authors and wits were invited. In 1749 Mr. Sheridan, the manager,[Pg 173] founded one at Dublin. There were fifty or sixty members, chiefly noblemen and members of Parliament, and no performer was admitted but witty Peg Woffington, who wore man’s dress, and was president for a whole season.[319]

A Beef-steak Society was founded in 1735 by John Rich, the great harlequin, and manager of Covent Garden Theatre, and George Lambert, the scene-painter.[320] Lambert, being much visited by authors, wits, and noblemen, whilst painting, and being too hurried to go to a tavern, used to have a steak cooked in the room, inviting his guests to share his snug and savoury but hurried meal. The fun of these accidental and impromptu dinners led to a club being started, which afterwards moved to a more convenient room in the theatre. After many years the place of meeting was changed to the Shakspere Tavern, where Mr. Lambert’s portrait, painted by Hudson, Reynolds’s pompous master, was one of the decorations of the club-room.[321] They then returned to the theatre, but being burned out in 1812, adjourned to the Bedford. Lambert was the merriest of fellows, yet without buffoonery or coarseness. His manners were most engaging, he was social with his equals, and perfectly easy with richer men.[322] He was also a great leader of fun at old Slaughter’s artist-club.

The club throve down to about 1869, when it was dissolved; steaks were perennial as a dish, whatever the wit may have been, to the last. Twenty-four noblemen and gentlemen, each of whom might bring a friend, partook of a five o’clock dinner of steaks in a room of their own behind the scenes at the Lyceum Theatre every Saturday from November till June. They called themselves “The Steaks,” disclaimed the name of “Club,” and dedicated their hours to “Beef and Liberty,” as their ancestors did in the anti-Walpole days.[323]

Their room was a little typical Escurial. The doors, wainscot, and floor, were of stout oak, emblazoned with[Pg 174] gridirons, like a chapel of St. Laurence. The cook was seen at his office through the bars of a vast gridiron, and the original gridiron of the society (the survivor of two terrific fires) held a conspicuous position in the centre of the ceiling. This club descended lineally from Wilkes’s and from Lambert’s. To the end there was Attic salt enough to sprinkle over “the Steaks,” and to justify the old epicure’s lines to the club:—

“He that of honour, wit, and mirth partakes,

May be a fit companion o’er beef-steaks;

His name may be to future times enrolled

In Estcourt’s book, whose gridiron’s framed of gold.”[324]

Its gridiron and other treasures were sold by auction, and fetched fabulous prices.

Dr. William King, the author of the above quoted verses, was an indolent, wrong-headed genius. Some three years after the Restoration he took part against the irascible Bentley in the dispute about the Epistles of Phalaris, satirised Sir Hans Sloane, and supported Sacheverell. He wrote The Art of Cookery, Dialogues of the Dead, The Art of Love, and Greek Mythology for Schools. Recklessly throwing up his Irish Government appointment, he came to London. There Swift got him appointed manager of the Gazette; but being idle, and fond of the bottle, he resigned his office in six months, and went to live at a friend’s house in the garden grounds between Lambeth and Vauxhall. He died in 1712, in lodgings opposite Somerset House, procured for him by his relation, Lord Clarendon. He was buried in the north cloisters of Westminster Abbey, close to his master, Dr. Knipe, to whom he had dedicated his School Mythology.

Mr. T. P. Cooke obtained some of his early triumphs at the Lyceum as Frankenstein, and at the Adelphi as Long Tom Coffin. His serious pantomime in the fantastic monster of Mrs. Shelley’s novel is said to have been highly poetical. He made his début in 1804, at the Royalty Theatre, and[Pg 175] soon afterwards left Astley’s to join Laurent, the manager of the Lyceum. This best of stage seamen since Bannister’s time was born in 1780, and died only recently.

Madame Lucia Elizabeth Vestris had the Lyceum in 1847. This fascinating actress was the daughter of Francesco Bartolozzi, the engraver, and was born in 1797. She married the celebrated dancer, Vestris, in 1813, and in 1813 appeared at the King’s Theatre, in Winter’s opera of “Proserpina.” In 1820, after a wild and disgraceful life in Paris, she appeared at Drury Lane as Lilla, Adela, and Artaxerxes, and exhibited the archness, and vivacity of Storace without her grossness. In a burlesque of “Don Giovanni,” as “Paul” and as “Apollo,” she was much abused by the critics for her wantonness of manner and dress, but she still won her audiences by her sweet and powerful contralto, and by her songs, “The Light Guitar” and “Rise, gentle Moon.” Harley played Leporello to her under Mr. Elliston’s management. After this she took to “first light comedy” and melodrama, and married Mr. Charles Mathews. The theatre was burnt down in 1830, and rebuilt soon afterwards. Madame Vestris herself died in 1856.

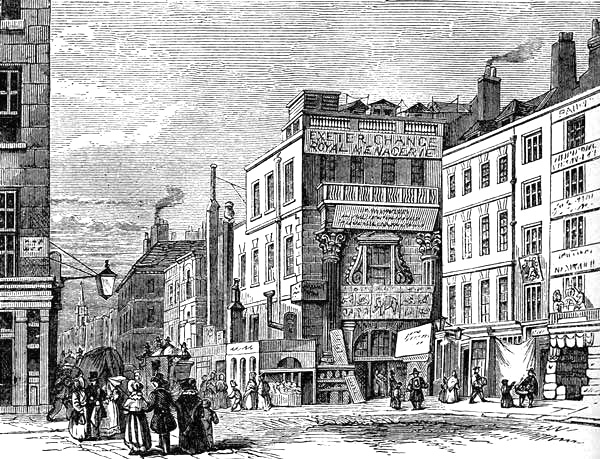

“That little crowded nest” of shops and wild beasts,[325] Exeter Change, stood where Burleigh Street now stands, but extended into the main road, so that the footpath of the north side of the Strand ran directly through it.[326] It was built about 1681,[327] and contained two walks below and two walks above stairs, with shops on each side for sempsters, milliners, hosiers, etc. The builders were very sanguine, but the fame of the New Exchange (now the Adelphi) blighted it from the beginning;[328] the shops next the street alone could be let; the rest lay unoccupied. The Land Bank had rooms here. The body of the poet Gay lay in state in an upper room, afterwards used for auctions. In 1721 a Mr. Normand Corry exhibited here a damask bed, with curtains woven by himself; admission two shillings and[Pg 176] sixpence. About 1780 Lord Baltimore’s body lay here in state, preparatory to its interment at Epsom.

This infamous lord, of unsavoury reputation, had married a daughter of the Duke of Bridgewater: he lived on the east side of Russell Square, and was notorious for an unscrupulous profligacy, rivalling even that of the detestable Colonel Charteris. In 1767 his agents decoyed to his house a young woman named Woodcock, a milliner on Tower Hill. After suffering all the cruelty which Lovelace showed to Clarissa, the poor girl was taken to Lord Baltimore’s house at Epsom, where her disgrace was consummated. The rascal and his accomplices were tried at Kingston in 1768, but unfortunately acquitted through an informality in Miss Woodcock’s deposition. The disgraced title has since become extinct.

The last tenants of the upper rooms were Mr. Cross and his wild beasts. The Royal Menagerie was a great show in our fathers’ days. Leigh Hunt mentions that one day at feeding time, passing by the Change, he saw a fine horse pawing the ground, startled at the roar of Cross’s lions and tigers.[329] The vast skeleton of Chunee, the famous elephant, brought to England in 1810, and exhibited here, is to be seen at the College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. In 1826, after a return of an annual paroxysm, aggravated by inflammation of the large pulp of one of his tusks, Chunee became dangerous, and it was necessary to kill him. His keeper first threw him buns steeped in prussic acid, but these produced no effect. A company of soldiers was then sent for, and the monster died after upwards of a hundred bullets had pierced him. In the midst of the shower of lead, the poor docile animal knelt down at the well-known voice of his keeper, to turn a vulnerable point to the soldiers. At the College of Surgeons the base of his tusk is still shown, with a spicula of ivory pressing into the pulp.

De Loutherbourg, after Garrick’s retirement, left Covent Garden and exhibited his Eidophusikon in a room over Exeter Change. The stage was about six feet wide and[Pg 177] eight feet deep. The first scene was the view from One-tree Hill in Greenwich Park. The lamps were above the proscenium, and had screens of coloured glass which could be rapidly changed. His best scenes were the loss of the Halsewell East Indiaman and the rising of Pandemonium. A real thunder-storm once breaking out when the shipwreck scene was going on, some of the audience left the room, saying that “the exhibition was presumptuous.” Gainsborough was such a passionate admirer of the Eidophusikon that for a time he spent every evening at Loutherbourg’s exhibition.[330]

Mr. William Clarke, a seller of hardware (steel buttons, buckles, and cutlery), was proprietor of Exeter Change for nearly half a century. He was an honest and kind man, much beloved by his friends, and known to everybody in Johnson’s time. When he became infirm he was allowed by King George the special privilege of riding across St. James’s Park to Buckingham Gate, his house being in Pimlico. He died rich.

Another character of Clarke’s age was old Thomson, a music-seller, and a good-natured humourist. He was deputy organist at St. Michael’s, Cornhill, and had been a pupil of Boyce. His shop was a mere sloping stall, with a little platform behind it for a desk, rows of shelves for old pamphlets and plays, and a chair or two for a crony. Thomson furnished Burney and Hawkins with materials for their histories of music. It was said that there was not an air from the time of Bird that he could not sing. Poor soured Wilson used to be fond of sitting with Thomson and railing at the times. Garrick and Dr. Arne also frequented the shop.[331]

The nine o’clock drum at old Somerset House and the bell rung as a signal for closing Exeter Change were once familiar sounds to old Strand residents: but alas! times are changed; and they are heard no more.

It was in Thomson’s shop that the elder Dibdin (Charles), together with Hubert Stoppelaer, an actor, singer, and[Pg 178] painter, planned the Patagonian Theatre, which was opened in the rooms above. The stage was six feet wide, the puppet actors only ten inches high. Dibdin wrote the pieces, composed the music, helped in the recitations, and accompanied the singers on a small organ. His partner spoke for the puppets and painted the scenes. They brought out “The Padlock” here. The miniature theatre held about 200 people.[332]

Exeter Hall was built by Mr. Deering, in 1831, for various charitable and religious societies that had scruples about holding their meetings in taverns or theatres. It stands a little west of the site of the “old Change.” The front, with its two massy plain Greek pillars, is a good instance of making the most of space, though it still looks as if it were riding “bodkin” between the larger houses. The building contains two halls—one that will hold eight hundred persons, and another, on the upper floor, able to hold three thousand. The latter is a noble room, 131 feet long by 76 wide, and contains the Sacred Harmonic Society’s gigantic organ. There are also nests of offices and committee-rooms. In May the white neckcloths pour into Exeter Hall in perfect regiments.

In the Strand, near Exeter House, lived the beautiful Countess of Carlisle, a beauty of Charles I.’s court, immortalised by Vandyke, Suckling, and Carew. She paid £150 a year rent, equal to £600 of our current money.[333]

Exeter Street had no western outlet when first built; for where the street ends was the back wall of old Bedford House. Dr. Johnson, after his arrival with Garrick from Lichfield, lodged here, in a garret, at the house of Norris, a staymaker. In this garret Johnson wrote part at least of that sonorous tragedy, “Irene.” He used to say he dined well and with good company for eightpence, at the Pine Apple in the street close by. Several of the guests had travelled. They met every day, but did not know each other’s names. The others paid a shilling, and had wine. Johnson paid sixpence for a cut of meat (a penny for bread,[Pg 179] a penny to the waiter), and was served better than the rest, for the waiter that is forgotten is apt also to forget.

In Cecil’s time Bedford House became known as Exeter House. From hence, in 1651, Cromwell, the Council of State, and the House of Commons followed General Popham’s body to its resting-place at Westminster.[334] It was while receiving the sacrament on Christmas Day at the chapel of Exeter House that that excellent gentleman, Evelyn, and his wife were seized by soldiers, warned not to observe any longer the “superstitious time of the Nativity,” and dismissed with pity.

In Exeter House lived that shifty and unscrupulous turncoat, Antony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, the great tormentor of Charles II., and the father of the author of the Characteristics, who was born here 1670-1, and educated by the amiable philosopher Locke. “The wickedest fellow in my dominions,” as Charles II. once called “Little Sincerity,” afterwards removed hence about the time of the Great Fire to Aldersgate Street, in order to be near his City intriguers. After the Great Fire, till new offices could be built, the Court of Arches, the Admiralty Court, etc., were held in Exeter House. The property still belongs to the Cecil family.

That great statesman, Burleigh, Bacon’s uncle, lived on the site of the present Burleigh Street. He was of birth so humble that his father could only be entitled a gentleman by courtesy. Slow but sure of judgment, silent, distrustful of brilliant men, such as Essex and Raleigh, he made himself, by unremitting skill, assiduity, and fidelity, the most trusted and powerful person in Queen Elizabeth’s privy council. Here, fresh from his frets with the rash Essex, the old wily statesman pondered over the fate of Mary of Scotland, or strove for means to foil Philip of Spain and his Armada. Here also lived his eldest son, Sir Thomas Cecil, subsequently the second Lord Burleigh and Earl of Exeter, who died 1622, whose daughter married the heir of Lord Chancellor Hatton, the dancing chancellor. Burleigh Street[Pg 180] replaced the old house in 1678, when Salisbury Street was built.

The “Little Adelphi” Theatre was opened in 1806 under the name of the “Sans Souci” by Mr. John Scott, a celebrated colour-maker, famous for a certain fashionable blue dye. The entertainments (optical and mechanical) were varied by songs, recitations, and dances, the proprietor’s daughter being a clever amateur actress. Its real success did not begin till 1821, when Pierce Egan’s dull and rather vulgar book of London low life, Tom and Jerry, was dramatised—Wrench as Tom, Reeve as Jerry. Subsequently Power, the best Irishman that trod the boards in London, appeared here in melodrama. In 1826 Terry and Yates became joint lessees and managers. Ballantyne and Scott backed up Terry, Sir Walter being always eager for money. Scott eventually had to pay £1750 for the speculative printer; he seems from the outset to have entertained fears of Terry’s failure.[335] Here Keely too made his first hit as Jemmy Green.

In 1839 Mr. Rice, “the original Jim Crow,” was playing at the Adelphi.[336] This Mr. Rice was an American actor who had studied the drolleries of the Negro singers and dancers, especially those of one Jim Crow, an old boatman who hung about the wharfs of Vicksburg, the same town on the Mississippi that has lately stood so severe a siege. He initiated among us negro tunes and negro dances. This was the fatal beginning of those “negro entertainments,” falsely so called.

In 1808 Mr. Mathews gave his first entertainment, “The Mail-coach Adventures,” at Hull. Mr. James Smith had strung together some sketches of character, and written for him those two celebrated comic songs, “The Mail Coach” and “Bartholomew Fair.” In 1818 Mr. Mathews, unfortunately for his peace of mind, sold himself for seven years to a very sharp practiser, Mr. Arnold, of the Lyceum, for £1000 a year, liable to the deduction of £200 fine for any non-appearance. This becoming unbearable, Mr.[Pg 181] Arnold made a new agreement, by which he took to himself £40 every night, and shared the rest with Mr. Mathews, who also paid half the expenses.[337] The shrewd manager made £30,000 by this first speculation. Rivalling Mr. Dibdin, the wonderful mimic appeared in plain evening dress with no other apparent preparation than a drawing-room scene, a small table covered with a green cloth, and two lamps. His first entertainment included “Fond Barney, the Yorkshire Idiot” and the “Song of the Royal Visitors,” full of droll Russian names. In 1819 he produced “The Trip to Paris.” In 1820 he brought out “The Country Cousins,” with the two celebrated comic songs, “The White Horse Cellar,” and “O, what a Town!—what a Wonderful Metropolis!” both full of the most honest and boisterous fun. In 1821 Peake wrote for him the “Polly Packet,” introducing a caricature of Major Thornton, the great sportsman, as Major Longbow. The entertainment was called “Earth, Air, and Water,” and contained the song of “The Steam-Boat.”

In 1824 Mr. Mathews gave his “Trip to America,” with Yankee songs, negro imitations, and that fine bit of pathos, “M. Mallet at the Post-Office.” In 1825 appeared his “memorandum Book,” and in 1826 his “Invitations,” with the “Ruined Yorkshire Gambler (Harry Ardourly),” and “A Civic Water Party.”

In 1828 he opened the Adelphi Theatre in partnership with Mr. Yates, playing the drunken Tinker in Mr. Buckstone’s “May Queen,” and singing that prince of comic songs, “The Humours of a Country Fair,” written for him by his son Charles. Mr. Moncrief wrote his “Spring Meeting for 1829,” and Mr. Peake his “Comic Annual for 1830.” In 1831 his son Charles aided Mr. Peake in producing an entertainment, and again in 1832. In 1833 his health began to fail; he lost much money in bubble companies, and had an action brought against him for £30,000. In 1833 Mr. Peake and Mr. Charles Mathews wrote the “At Home.”[Pg 182] Subsequently the great mimic went to America, whence he returned in 1838, only to die a few months after.[338]

Leigh Hunt praises Mr. Mathews’s valets and old men, but condemns his nervous restlessness and redundance of bodily action. While Munden, Liston, and Fawcett could not conceal their voices, Mathews rivalled Bannister in his powers of mimicry. His delineation of old age was remarkable for its truthfulness and variety. Leigh Hunt confesses that till Mathews acted Sir Fretful Plagiary, he had ranked him as an actor of habits and not of passions, and far inferior to Bannister and Dowton; but the extraordinary blending of vexation and conceit in Sheridan’s caricature of Cumberland proved Mathews, Mr. Hunt allowed, to be an actor who knew the human heart.[339]

In 1820 Hazlitt criticised Mathews’s third entertainment, “The Country Cousins,” a mélange of songs, narrative, ventriloquism, imitations, and character stories. He had left Covent Garden on the ground that he had not sufficiently frequent opportunities for appearing in legitimate comedy. The severe critic says, “Mr. Mathews shines particularly neither as an actor nor a mimic of actors; but his forte is a certain general tact and versatility of comic power. You would say he is a clever performer—you would guess he is a cleverer man. His talents are not pure, but mixed. He is best when he is his own prompter, manager, performer, orchestra, and scene-shifter.”[340]

Hazlitt then goes on to accuse his “subject” of a want of taste, of his gross and often superficial surprises, and of his too restless disquietude to please. “Take from him,” says Hazlitt, “his odd shuffle in the gait, a restless volubility of speech and motion, a sudden suppression of features, or the continued repetition of a cant phrase with unabated vigour, and you reduce him to almost total insignificance.” It should be said that his “shuffle” was rather a “limp.”

As a mimic of other actors, the same writer says Mathews[Pg 183] often failed. He gabbled like Incledon, entangled himself like Tait Wilkinson, croaked like Suett, lisped like Young, but he could make nothing of John Kemble’s “expressive, silver-tongued cadences.” He blames him more especially for turning nature into pantomime and grimace, and dealing too much with worn-out topics, like Cockneyisms, French blunders, or the ignorance of country people in stage-coaches, Margate hoys, and Dover packet-boats. In another place the severe critic, who could be ill-tempered if he chose, blames Mathews for many of his songs, for his meagre jokes, dry as scrapings of “Shabsuger cheese,” and for his immature ventriloquism. “His best imitations,” says Hazlitt, “were founded on his own observation, and on the absurd characteristics of chattering footmen, drunken coachmen, surly travellers, and garrulous old men. His old Scotchwoman, with her pointless story, was a portrait equal to Wilkie or Teniers, as faithful, as simple, as delicately humorous, with a slight dash of pathos, but without one particle of caricature, vulgarity, or ill-nature.” His best broad jokes were these: the abrupt proposal of a mutton-chop to a man who was sea-sick, and the convulsive marks of abhorrence with which he received it; and the tavern beau who was about to swallow a lighted candle for a glass of brandy-and-water as he was going drunk to bed. Poor Wiggins, the fat, hen-pecked husband, who, unwieldy and helpless, is pursued by a rabble of boys, was one of his best characters. Hazlitt mentions also as a stroke of true genius his imitation of a German family, the wife grumbling at her husband returning drunk, and the little child’s paddling across the room to its own bed at its father’s approach.[341]

Terry, who in 1825 joined partnership with Yates, and died in 1829, was a quiet, sensible actor, praised in his Mephistopheles, and even in King Lear. His Peter Teazle was inferior to Farren’s, and his Dr. Cantwell came after Dowton’s.

Yates was born in 1797. He made his début at Covent Garden as Iago in 1818. He was very versatile, and[Pg 184] triumphed alternately in tragedy, comedy, farce, and melodrama. A critic of 1834 says, “Mr. Yates is occasionally capital, and always respectable. In burlesque he is excellent, but a little too broad, and given to an exaggeration which is sometimes vulgar. He is a better buck than fop, and a better rake than either, were he more refined.”

John Reeve was another of the Adelphi celebrities. He was born in 1799, and was originally a clerk at a Fleet Street banking-house. He appeared first at Drury Lane in 1819 as Sylvester Daggerwood. His imitations were pronounced perfect, and he soon rose to great celebrity in broad farce, burlesque, and the comic parts of melodrama. Lord Grizzle, Bombastes, and Pedrillo, were favourite early characters of his. He was considered too heavy for Caleb Quotem, and not quiet enough for Paul Pry. Liston excelled him in the one, and Harley in the other.

Benjamin Webster was born at Bath in 1800. He took the management of the Haymarket in 1837, and built the New Adelphi Theatre in 1858. In melodrama Mr. Webster excels. His best parts are—Lavater, Tartuffe, Belphegor, Triplet, and Pierre Leroux in “The Poor Stroller.” He is excellent in poor authors and strolling players, and achieved a great triumph in Mr. Watts Philips’s play of “The Dead Heart.” He is energetic and forcible, but he has a bad hoarse voice, and he protracts and details his part so elaborately as often to become tedious.

In 1844 Madame Celeste, who in 1837 had appeared at Drury Lane on her return from America, was directress of the Adelphi. She then left and took the Lyceum, which she held until the close of 1860-1.

The old Adelphi closed in June 1858. Although a small and incommodious house, it had long earned a special fame of its own. It began its career with “True Blue Scott,” and went on with Rodwell and Jones during the “Tom and Jerry” mania, when young men about town wrenched off knockers, knocked down old men who were paid to apprehend thieves, and attended beggars’ suppers. Under Terry and Yates, Buckstone and Fitzball produced pieces in which[Pg 185] T. P. Cooke, O. Smith, Wilkinson, and Tyrone Power shone (this actor was drowned in 1841). There also flourished Wright, Paul Bedford, Mrs. Yates, and Mrs. Keeley, in “The Pilot,” “The Flying Dutchman,” “The Wreck Ashore,” “Victorine,” “Rory O’More,” and “Jack Sheppard,”[342]—the last of these a play to be branded as a demoralising apotheosis of a clever thief.

In 1844 Mr. Webster became proprietor of the Adelphi, and Madame Celeste, a good melodramatic actress, became the directress. Then was brought out that crowning triumph of the theatre, “The Green Bushes,” by Mr. Buckstone—a tremendous success.

Among the greatest “hits” at the Adelphi have been of later years Mr. Watts Philips’s “Dead Heart,” a powerful melodrama of the French Revolution period, Miss Bateman’s “Leah,” an American-German play of the old school, and “The Colleen Bawn,” Mr. Boucicault’s clever dramatic version of poor Gerald Griffin’s novel, full of fine melodramatic situations.

The old town house of the Earls of Bedford stood on the site of the present Southampton Street, and was taken down in 1704, in Queen Anne’s reign. It was a large house with a courtyard before it, and a spacious garden with a terrace walk.[343] Before this house was built the Bedford family lived at the opposite side of the Strand, in the Bishop of Carlisle’s inn, which, in 1598, was called Russell or Bedford House.[344] In 1704 the family removed to Bloomsbury. The neighbouring streets were christened by this family. Russell Street bears their family name, and Tavistock Street their second title.

Garrick lived at No. 36 Southampton Street before he went to the Adelphi. In 1755, to give himself some rest, he brought out a magnificent ballet pantomime, called “The Chinese Festival,” composed by “the great Noverre.” Unfortunately for Garrick, war had just broken out between England and France, and the pit and gallery condemned the[Pg 186] Popish dancers in spite of King George II. and the quality. Gentlemen in the boxes drew their swords, leaped down into the pit, and were bruised and beaten. The galleries looked on and pelted both sides. The ladies urged fresh recruits against the pit, and each fresh levy was mauled. The pit broke up benches, tore down hangings, smashed mirrors, split the harpsichords, and storming the stage, cut and slashed the scenery.[345] The rioters then sallied out to Mr. Garrick’s house (now Eastey’s Hotel) in Southampton Street, and broke every window from basement to garret.

Mrs. Oldfield, who lived in Southampton Street, was the daughter of an officer, and so reduced as to be obliged to live with a relation who kept the Mitre Tavern in St. James’s Market. She was overheard by Mr. Farquhar reading a comedy, and recommended by him to Sir John Vanbrugh. She was excellent as Lady Brute and also as Lady Townley. She died in 1730; her body lay in state in the Jerusalem Chamber, and was afterwards buried in the Abbey. Lord Hervey and Bubb Doddington supported her pall. Her corpse, by her own request, was richly adorned with lace—a vanity which Pope ridiculed in those bitter lines—

“One would not sure be ugly when one’s dead;

And, Betty, give this cheek a little red.”

In 1712 Arthur Maynwaring, in his will, describes this street as New Southampton Street.

Bedford Street was first so named in 1766 by the Paving Commissioners. The lower part of the street was called Half-Moon Street; after the fire of London it became fashionable with mercers, lacemen, and drapers.[346] The lower part of the street is in the parish of St. Martin’s in the Fields, the upper in that of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden. In the overseers’ accounts of St. Martin’s mention is made of the names of persons who were fined in 1665 for drinking on the Lord’s Day at the Half-Moon Tavern in this street, also for carrying linen, for shaving customers, for carrying home venison or a pair of shoes, and for swearing. Sir[Pg 187] Charles Sedley and the Duke of Buckingham were fined by the Puritans in 1657-58 for riding in their coaches on that day.[347] Ned Ward, the witty publican, in his London Spy, mentions the Half-Moon Tavern in this street.

On the eastern side of the same street, in 1645, lived Remigius van Limput, a Dutch painter, who, at the sale of King Charles’s pictures, bought Vandyke’s florid masterpiece, now at Windsor, of the king on horseback. After the Restoration he was compelled to disgorge it. Had this grand picture been the portrait of any better king, Cromwell would not have parted with it.

The witty bulky Quin lived here from 1749 to 1752. It was in 1749 that this great tragedian, reappearing after a retirement, performed in his friend Thomson’s posthumous play of “Coriolanus.” Good-natured Quin had once rescued the fat lazy poet from a sponging-house. It was about this time that the great elocutionist was instructing Prince George in recitation. When, afterwards, as king, he delivered his first speech successfully in Parliament, the actor exclaimed triumphantly, “Sir, it was I taught the boy.”