Haunted London, Index

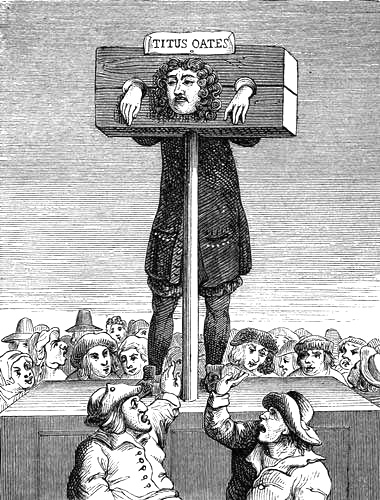

TITUS OATES IN THE PILLORY.

CHAPTER IX.

CHARING CROSS.

On July 20, 1864, was laid the first stone of the great Thames Embankment, which now forms the wall of our river from Blackfriars to Westminster. A couple of flags fluttered lazily over the stone as a straggling procession of the members of the Metropolitan Board of Works moved down to[Pg 191] the wooden causeway leading to the river. For two years about a thousand men were at work on it night and day. Iron caissons were sunk below the mud, deep in the gravel, and within ten feet of the clay which is the real foundation of London, and the Victoria Embankment rose gradually into being. It was opened by Royalty in the summer of 1870. This scheme, originally sketched out by Wren, was designed by Colonel Trench, M.P., and also by Martin the painter; but it was never carried out until the days of Lord Palmerston and the Metropolitan Board of Works. Its piers, its flights of steps, its broad highway covering a railway, its gardens, its terraces, are complete; and when the buildings along it are finished London may for the first time claim to compare itself in architectural grandeur with Nineveh, Rome, or modern Paris.

Northumberland House, which faced Charing Cross, covering the site of Northumberland Avenue, was a good but dull specimen of Jacobean architecture; it was built by Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton, son of the poet Earl of Surrey, about 1605.[349] Walpole attributes the building to Bernard Jansen, a Fleming, and an imitator of Dieterling, and to Gerard Christmas, the designer of Aldersgate. Jansen probably built the house, which was of brick, and Christmas added the stone frontispiece, which was profusely ornamented with rich carved scrolls, and an open parapet worked into letters and other devices. John Thorpe is also supposed to have been associated in the work; and plans of both the quadrangles of this enormous palace are preserved among the Soane MSS.[350] Jansen was the architect of Audley End, in Essex, one of the wonders of the age. Thorpe built Burghley. The front was originally 162 feet long, the court 82 feet square; as Inigo Jones has noted in a copy of Palladio preserved at Worcester College, Oxford.

The Earl of Northampton left the house by his will, in 1614, to his nephew, Thomas Howard, Earl of Suffolk, who died in 1626. This was the father of the memorable[Pg 192] Frances, Countess of Essex and Somerset; and from him the house took the name of Suffolk House, till the marriage in 1642 of Elizabeth, daughter of Theophilus, second Earl of Suffolk, with Algernon Percy, tenth Earl of Northumberland, when it changed its name accordingly.

Dorothy, sister of the rash and ungrateful Earl of Essex, whose violence and follies nothing less than the executioner’s axe could cure, married the “wizard” Earl of Northumberland, as he was called, whom “she led the life of a dog, till he indignantly turned her out of doors.” He was afterwards engaged in the Gunpowder Plot, being angry with the Government that had overlooked him. “His name was used and his money spent by the conspirators; one of his servants hired the vault, and procured the lease of Vineyard House. Thomas Percy, his kinsman and steward, supped with him on the very night of the plot. His servant, Sir Dudley Carleton, who hired the house, was thrust into the Tower, and the earl joined him there not long after; but Cecil was either unable or unwilling to touch his life.”[351] Northumberland, with Cobham and Raleigh, had before this engaged in schemes with the French against the Government. Thomas Percy had been beheaded for plotting with Mary. Henry Percy had shot himself while in the Tower, on account of the Throckmorton Conspiracy. Compounding for a fine of £11,000, the earl devoted himself in the Tower to scientific and literary pursuits, and gave annuities to six or seven eminent mathematicians, who ate at his table. In 1611 he was again examined, and finally released in 1617. The king’s favourite, Hay, afterwards Earl of Carlisle, had married the earl’s daughter Lucy against his will, which so irritated him that he was with difficulty persuaded to accept his own release, because it was obtained through the intercession of Hay.

Joceline Percy, son of Algernon, dying in 1670, without issue male, Northumberland House became the property of his only daughter Elizabeth Percy, the heiress of the Percy estates. Her first husband was Henry Cavendish, Earl of[Pg 193] Ogle; her second, Thomas Thynne, of Longleat, in Wilts, who was shot in his coach in Pall Mall, on Sunday, February 12, 1681-2; her third husband was Charles Seymour, the proud Duke of Somerset, who married her in 1682. This lady was twice a widow and three times a wife before the age of seventeen.

The “proud” duke and duchess lived in great state and magnificence at Northumberland House. The duchess died in 1722, and the duke followed in 1748. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Algernon, Earl of Hertford, and the seventh Duke of Somerset, who was created Earl of Northumberland in 1749, with remainder, failing issue male, to his son-in-law, Sir Hugh Smithson, who in 1766 was raised to the dukedom. The lion which country cousins for two centuries remember to have crowned the central gateway of the duke’s house, represented the Percy crest. It is of this stiff-tailed animal, for the exact angle of the tail is treated by heralds as a matter of the most vital importance, that the old story imputed to Sheridan is told. Probably some audacious wit did once collect a London crowd by declaring that its tail wagged—but certainly it was not Sheridan.

Tom Thynne, or, as he was called, “Tom of Ten Thousand,” was shot at the east end of Pall Mall, opposite the Opera Arcade, by Borosky, a Polish soldier urged on by Count Königsmark, a Swedish adventurer, son of one of Gustavus’s old generals, and who was enraged with Thynne for having just married the youthful widow of the Earl of Ogle, Lady Elizabeth Percy. Thynne was a favourite of the Duke of Monmouth. Shaftesbury had been lately released from the Tower, in spite of Dryden’s onslaught on him as “Achitophel,” on the foolish duke as “Absalom,” and on Thynne as “Issachar,” his wealthy western friend. The three murderers were hanged in Pall Mall, but their master strangely escaped, partly owing to the influence of Charles II. The count, who had shown great courage at Tangier against the Moors, and had boarded a Turkish galley at his eminent peril, died in 1686, at the battle of Argos in the Morea. His younger brother was assassinated at[Pg 194] Hanover, on suspicion of an intrigue with Sophia of Zell, the young and beautiful wife of the Elector, afterwards George I. of England.[352]

The Earl of Northampton, Surrey’s son, who built Northumberland House (as Osborne, who loved scandal, says with Spanish gold), seems to have been an unscrupulous time-server, flatterer, and parasite. In 1596 he wrote to Burleigh, and spoke of his reverend awe at his lordship’s “piercing judgment;” yet a year after he writes a plotting letter to Burleigh’s great enemy, Essex, and says: “Your lordship by your last purchase hath almost enraged the dromedary that would have won the Queen of Sheba’s favour by bringing pearls. If you could once be so fortunate in dragging old Leviathan (Burghley) and his rich tortuosum colubrum (Sir Robert Cecil), as the prophet termeth them, out of their den of mischievous device, the better part of the world would prefer your virtue to that of Hercules.” The earl became a toady and creature of the infamous Carr, Earl of Somerset, and is thought to have died just in time to escape prosecution for the poisoning of Sir Thomas Overbury in the Tower.[353]

It was shortly before Suffolk House changed its name that it became the scene of one of Lord Herbert of Cherbury’s mad Quixotic quarrels. His chivalrous lordship had had sundry ague fits, which had made him so lean and yellow that scarce any man could recognise him. Walking towards Whitehall he one day met a Mr. Emerson, who had spoken very disgraceful words of Lord Herbert’s friend, Sir Robert Harley. Lord Herbert therefore, sensible of the dishonour, took Emerson by his long beard, and then, stepping aside, drew his sword; Captain Thomas Scriven being with Lord Herbert, and divers friends with Mr. Emerson. All who saw the quarrel wondered at the Welsh nobleman, weak and “consumed” as he was, offering to fight; however, Emerson ran and took shelter in Suffolk House, and afterwards complained to the Lords in[Pg 195] Council, who sent for Lord Herbert, the lean, yellow Welsh Quixote, but did not so much reprehend him for defending the honour of his friend as for adventuring to fight, being at the same time in such weak health.[354]

Algernon, the tenth Earl of Northumberland, is called by Clarendon “the proudest man alive.” He had been Lord High Admiral to King Charles I., and was appointed general against the Scotch Covenanters, but, being unable to take the command from ill health, gave up his commission. He gradually fell away from the king’s cause, but nevertheless refused to continue High Admiral against the king’s wish. He treated the Dukes of York and Gloucester and the Princess Elizabeth with “such consideration” that they were removed from his care, and from that time he turned Royalist again.

Sir John Suckling refers to Suffolk House in his exquisite little poem on the wedding of Roger Boyle, Lord Broghill, with Lady Margaret Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk. The well known poem begins—

“At Charing-cross, hard by the way

Where we (thou know’st) do sell our hay,

There is a house with stairs.”

And then the gay and graceful poet goes on to sketch Lady Margaret—

“Her lips were red, and one was thin,

Compared with that was next her chin.

Some bee had stung it newly.”

And then follows that delightful, fantastic simile, comparing her feet to little mice creeping in and out her petticoat.[355] Sir John was born in 1609.

The oldest part of Northumberland House was the Strand entrance. This was crowned, as stated above, by a frieze or balustrade of large stone letters, probably including the name and titles of the earl and the glorified name of the architect. At the funeral of Anne of Denmark, 1619, a young man, named Appleyard, was killed by the fall of the[Pg 196] letter S[356] from the house, which was then occupied by the Earl of Strafford, Lord Treasurer. The house was originally only three sides of a quadrangle, the river side remaining open to the gardens; but traffic and noise increasing, the quadrangle was completed along the river side and the principal apartments. There is a drawing by Hollar of the house in his time, and another, a century later, by Canaletti. The new front towards the gardens was spoiled by a clumsy stone staircase, which was attributed to Inigo Jones, but probably incorrectly.

The date, 1746, on the façade referred to the repairs made in that year, and the letters “A. S. P. N.” stood for Algernon Somerset, Princeps Northumbriæ. The lion over the gateway was said to be a copy of one by Michael Angelo; it is now at Sion House, Isleworth. The gateway was covered with ornaments and trophies. Double ranges of grotesque pilasters enclosed eight niches on the sides, and there was a bow window and an open arch above the chief gate. Between each of the fourteen niches in the front there were trophies of crossed weapons, and the upper stories had twenty-four windows, in two ranges, and pierced battlements. Each wing terminated in a little cupola, and the angles had rustic quoins. The quadrangle within the gate was simpler and in better taste, and the house was screened from the river by elm trees.[357]

There used to be a schoolboy tradition, prevalent at King’s College in the author’s time, that one of the niches in the front of Northumberland House was of copper and movable. So far the story was true; but the tradition went on to relate how, once upon a time, a certain enemy of the house of Percy obtained secret admission by this niche and murdered one of the dukes, his enemy. History is, however, fortunately, quite silent on this subject.

In February 1762 Horace Walpole and a party of quality set out from Northumberland House to hear the ghost in Cock Lane that Dr. Johnson exposed, and that Hogarth and Churchill ridiculed with pen and pencil. The[Pg 197] Duke of York, Lady Northumberland, Lady Mary Coke, and Lord Hertford, all returned from the Opera with Horace Walpole, then changed their dress, and set out in a hackney coach. It rained hard, and the lane and house were “full of mob.” The room of the haunted house, small and miserable, was stuffed with eighty persons, and there was no light but one tallow candle. As clothes-lines hung from the ceiling, Walpole asked drily if there was going to be rope-dancing between the acts. They said the ghost would not come till 7 A.M., when only ’prentices and old women remained. The party stayed till half-past one. The Methodists had promised contributions, provisions were sent in like forage, and the neighbouring taverns and ale-houses were making their fortunes.[358]

On May 14, 1770, poor Chatterton, who suffered so terribly for the deceptions of his ambitious boyhood, writes from the King’s Bench (for the present) that a gentleman who knew him at the Chapter coffee-house, in Paternoster Row—frequented by authors and publishers—would have introduced him to the young Duke of Northumberland as a companion in his intended general tour, “but, alas! I spake no tongue but my own.”[359] But this is taken from a most questionable work, full of fictions and forgeries. Its author was a Bristol man, who afterwards fled to America. He also wrote a series of Conversations with the poets of the Lake school, many of which are too obviously imaginary.

On March 18, 1780, the Strand front of Northumberland House was totally destroyed by fire. The apartments of Dr. Percy, the Duke’s kinsman and chaplain, afterwards Bishop of Dromore and editor of the Reliques of Ancient Poetry were consumed; but great part of his library escaped.

Goldsmith’s simple-hearted ballad of Edwin and Angelina was originally “printed for the amusement of the Countess of Northumberland.” Two years after, Kenrick accused him in the papers of plagiarising it from Percy’s pasticcio[Pg 198] from Shakspere in the Reliques, which was probably written in 1765.[360]

It is probable that Goldsmith often visited Percy, when acting as chaplain at Northumberland House. Sir John Hawkins, indeed, describes meeting the poet waiting for an audience in an outer room. At his own audience Hawkins mentioned that the doctor was waiting. On their way home together, Goldsmith told Hawkins that his lordship said that he had read the Traveller with delight, that he was going as Lord Lieutenant to Ireland, and should be glad, as Goldsmith was an Irishman, to do him any kindness. Hawkins was enraptured at the rich man’s graciousness. But Goldsmith had mentioned only his brother, a clergyman there, who needed help. “As for myself,” he added, bitterly, “I have no dependence on the promises of great men. I look to the booksellers for support; they are my best friends, and I am not inclined to forsake them for others.” “Thus,” says Hawkins, “did this idiot in the affairs of the world trifle with his fortunes and put back the hand that was held out to assist him.” The earl told Percy, after Goldsmith’s death, that had he known how to help the poet he would have done so, or he would have procured him a salary on the Irish establishment that would have allowed him to travel. Let men of the world remember that the poet a few days before had been forced to borrow 15s. 6d. to meet his own wants.

This conversation took place in 1765. In 1771, when Goldsmith was stopping at Bath with his good-natured friend Lord Clare, he blundered by mistake at breakfast time into the next door on the same Parade, where the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland were staying. As he took no notice of them, but threw himself carelessly on a sofa, they supposed there was some mistake, and therefore entered into conversation with him, and when breakfast was served up, invited him to stay and partake of it. The poet, hot, stammering, and irrecoverably confused, withdrew with profuse apologies for his mistake, but not till he had accepted an[Pg 199] invitation to dinner. This story, a parallel to the laughable blunder in She Stoops to Conquer, was told by the duchess herself to Dr. Percy.

It was probably of the first of these interviews that Goldsmith used to give the following account:—

“I dressed myself in the best manner I could, and, after studying some compliments I thought necessary on such an occasion, proceeded to Northumberland House, and acquainted the servants that I had particular business with the duke. They showed me into an ante-chamber, where, after waiting some time, a gentleman, very elegantly dressed, made his appearance. Taking him for the duke, I delivered all the fine things I had composed, in order to compliment him on the honour he had done me; when to my fear and astonishment, he told me I had mistaken him for his master, who would see me immediately. At that instant the duke came into the apartment, and I was so confounded on the occasion that I wanted words barely sufficient to express the sense I entertained of the duke’s politeness, and went away exceedingly chagrined at the blunder I had committed.”[361]

Dr. Waagen, the picture critic, seems to have been rather dazzled at the splendour of Northumberland House. He praises the magnificent staircase, lighted from above and reaching up through three stories, the white marble floors, the balustrades and chandeliers of gilt bronze, the cabinets of Florentine mosaic, and the arabesques of the drawing-room.[362] The great picture of the duke’s collection was the Cornaro family, by Titian; I believe from the Duke of Buckingham’s collection. It is a splendid specimen of the painter’s middle period and golden tone. The faces of the kneeling Cornari are grand, simple, senatorial, and devout. There was also a Saint Sebastian, by Guercino, “clear and careful,” and large as life; a fine Snyders and Vandyke; many copies by Mengs (particularly “The School of Athens”); and a good Schalcken, with his usual candlelight effect. The gem of all the English pictures was one[Pg 200] by Dobson, Vandyke’s noble pupil. It contained the portrait of the painter and those of Sir Balthasar Gerbier, the architect, and Sir Charles Cotterell. The colour is as rich and juicy as Titian’s, the drapery learned and graceful, the faces are full of fire and spirit. Dobson died at the age of thirty-six. Sir Charles was his patron.[363] Vandyke is said to have disinterred Dobson from a garret, and recommended him to the king. Gerbier was a native of Antwerp, a painter, architect, and ambassador. This picture of Dobson was bought at Betterton’s sale for £44.[364] The gallery of the Duke of Northumberland was removed in 1875, when the house was demolished, to Sion House.

Northumberland House was connected with, at all events, one period of English history. In the year 1660, when General Monk was in quarters at Whitehall, the Earl of Northumberland, in the name of the nobility and gentry of England, invited him here to the first conference in which the restoration of the Stuarts was publicly talked of. Algernon Percy, the tenth earl, had been Lord High Admiral under Charles I.

That staunch, brave, crotchety man, Sir Harry Vane the younger (the son of Lord Strafford’s enemy), lived next door to Northumberland House, eastwards, in the Strand. The house in Charles II.’s time became the official residence of the Secretary of State, and Mr. Secretary Nicholas dwelt there, when meetings were held to found a commonwealth and put down that foolish, good-natured, incompetent Richard Cromwell. To the great Protector, Vane was a thorn in the flesh, for he wanted a republic when the nation required a stronger and more compact government. Oliver’s exclamation, “Oh, Sir Harry Vane! Sir Harry Vane!—The Lord deliver me from Sir Harry Vane!” expresses infinite vexation with an impracticable person. Vane was a “Fifth-monarchy man,” and believed in universal salvation. He must have been a good man, or Milton would never have addressed the sonnet to him in which he says—

[Pg 201]

“Therefore, on thy firm hand Religion leans

In peace, and reckons thee her eldest son.”

Sir Harry left behind him some very tough and dark treatises on prophecy, and other profound matters that few but angels or fools dare to meddle with.

There is a foolish tradition that Charing Cross was so named originally by Edward I. in memory of his chère reine. Peele, one of the glorious band of Elizabethan dramatists, helped to spread this tradition. He makes King Edward say—

“Erect a rich and stately carved cross,

Whereon her statue shall with glory shine;

And henceforth see you call it Charing Cross.

For why?—the chariest and the choicest queen

That ever did delight my royal eyes

There dwells in darkness.”[365]

The inconsolable widower, however, in spite of his costly grief, soon married again.

The truth is, there are in England one or two Charings; one of them is a village thirteen miles from Maidstone. “Ing” means meadow in Saxon.[366] The meaning of “Char” is uncertain; it may be the contraction of the name of some long-forgotten landowner, “rich in the possession of dirt.”[367] The Anglo-Saxon word cerre—a turn (says Mr. Robert Ferguson, an excellent authority), is retained in the name given in Carlisle and other northern towns to the chares, or wynds—small streets. In King Edward’s time Charing was bounded by fields, both north and west. There has been a good deal of nonsense, however, written about “the pleasant village of Charing.” In Aggas’s map, published under Elizabeth, Hedge Lane (now Whitcombe Street) is a country lane bordered with fields; so is the Haymarket, and all behind the Mews up to St. Martin’s Lane is equally rural.

Horne Tooke[368] derives the word Charing from the Saxon verb charan—to turn; but the etymology is still doubtful, however much the river may bend on its way to[Pg 202] Westminster. However, doubtless, the place was named Charing as far back as the Saxon times.

It was Peele also who kept alive the old tradition of Queen Eleanor sinking at Charing Cross and rising again at Queenhithe. When falsely accused of her crimes, his heroine replies in the words of a rude old ballad well known in Elizabeth’s time—

“If that upon so vile a thing

Her heart did ever think,

She wished the ground might open wide,

And therein she might sink.

With that at Charing Cross she sank

Into the ground alive,

And after rose with life again,

In London at Queenhithe.”[369]

The Eleanor crosses were erected at Lincoln, Geddington, Northampton, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St. Albans, Waltham, Cheap, and Charing. Three only now remain,—Northampton, Geddington, and Waltham. Charing Cross was probably the most costly; it was octagonal, and was adorned with statues in tiers of niches, which were crowned with pinnacles. It was begun by Master Richard de Crundale, “cementarius,” but he died about 1293, before it was finished, and the work went on under the supervision of Roger de Crundale. Richard received about £500 for his work, exclusive of materials furnished him, and Roger £90: 7: 5. The stone was brought from Caen, and the marble steps from Corfe in Dorsetshire. Only one foreigner was employed on all the crosses, and he was a Frenchman. The Abbot Ware brought mosaics, porphyry, and perhaps designs from Italy, but there is no proof that he brought over Cavallini. A replica of the original cross, designed by Mr. Barry, has been erected at the west end of the Strand, opposite the Charing Cross Railway Station and Hotel.

The cluster of houses at Charing acquired the name of Cross from the monument set up by Edward I. to the[Pg 203] memory of his gentle, pious, and brave wife Eleanor, the sister of Alphonso, King of Castille. This good woman was the daughter of Ferdinand III., and after the death of her mother, heiress of Ponthieu. She bore to her fond husband four sons and eleven daughters, of whom only three are supposed to have survived their father.

Queen Eleanor died at Hardley, near Lincoln, in 1290. The king followed the funeral to Westminster, and afterwards erected a cross to his wife’s memory at every place where the corpse rested for the night. In the circular which the king sent on the occasion to his prelates and nobles, he trusts that prayers may be offered for her soul at these crosses, so that any stains not purged from her, either from forgetfulness or other causes, may through the plenitude of the Divine grace be removed.[370] It was Queen Eleanor who, when Edward was stabbed at Acre, by an emissary of the Emir of Joppa, according to a Spanish historian,[371] sucked the poison from the wounds at the risk of her own life.

This warlike king, who subdued Wales and Scotland, who expelled the Jews from England, who hunted Bruce, hanged Wallace, and who finally died on his march to crush Scotland, had a deep affection for his wife, and strove by all that art could do to preserve her memory.

Old Charing Cross was long supposed to have been built from the designs of Pietro Cavallini, a contemporary of Giotto. He is said to have assisted that painter in the great mosaic picture over the chief entrance of St. Peter’s. But there is little ground for accepting the tradition as true, though asserted by Vertue, as we learn from Horace Walpole’s ‘Anecdotes.’ Cavallini was born in 1279, and died in 1364. The monument to Henry III. at the Abbey, and the old paintings round the chapel of St. Edward are also attributed to this patriarch of art by Vertue.[372]

Queen Eleanor had three tombs—one in Lincoln Cathedral, over her viscera; another in the church of the[Pg 204] Blackfriars in London, over her heart; a third in Westminster Abbey, over the rest of her body. The first was destroyed by the Parliamentarians; the second probably perished at the dissolution of the monasteries; the third has escaped. It is a valuable example of the thirteenth century beau-ideal. The tomb was the work of William Torel, a London goldsmith. The statue is not a portrait statue any more than the statue of Henry III. by the same artist. Torel seems to have received for his whole work about £1700 of our money.[373]

The beautiful cross, with its pinnacles and statues, was demolished in 1647 under an order of the House of Commons, which had remained dormant for three years; and at the same time fell its brother cross in Cheapside.

The Royalist ballad-mongers, eager to catch the Puritans tripping, produced a lively street song on the occasion, beginning—

“Undone, undone the lawyers are,

They wander about the town,

Nor can find the way to Westminster,

Now Charing Cross is down.

At the end of the Strand they make a stand,

Swearing they are at a loss,

And chaffing say that’s not the way,

They must go by Charing Cross.”

The ballad-writer goes on to deny that the Cross ever spoke a word against the Parliament, though he confesses it might have inclined to Popery; for certain it was that it “never went to church.”

The workmen were engaged for three months in pulling down the Cross.[374] Some of the stones went to form the pavement before Whitehall; others were polished to look like marble, and were sold to antiquaries for knife-handles. The site remained vacant for thirty-one years.

After the Restoration Charing Cross was turned into a place of execution. Here Hugh Peters, Cromwell’s[Pg 205] chaplain, and Major-General Harrison, the sturdy Anabaptist, Colonel Jones, and Colonel Scrope were executed. They all died bravely, without a doubt or a fear.

Harrison was the son of a Staffordshire farmer, and had fought bravely at the siege of Basing; he had been major-general in Scotland; had helped Cromwell at the disbanding of the Rump; had served in the Council of State; and finally having expressed honest Anabaptist scruples about the Protectorate, had been imprisoned to prevent rebellion. Cromwell’s son Oliver had been captain in Harrison’s regiment.[375] As he was led to the scaffold some base scullion called out to the brave old Ironside, “Where is your good old cause now?” Harrison replied with a cheerful smile, clapping his hand on his breast, “Here it is, and I am going to seal it with my blood.” When he came in sight of the gallows he was transported with joy; his servant asked him how he did? He answered, “Never better in my life.” His servant told him, “Sir, there is a crown of glory prepared for you.”[376] “Yes,” replied he, “I see.” When he was taken off the sledge, the hangman desired him to forgive him. “I do forgive thee,” said he, “with all my heart, as it is a sin against me,” and told him he wished him all happiness; and further said, “Alas, poor man, thou dost it ignorantly; the Lord grant that this sin may not be laid to thy charge!” and putting his hand into his pocket he gave him all the money he had; and so parting with his servant, hugging him in his arms, he went up the ladder with an undaunted countenance. The cruel rabble observing him tremble in his hands and legs, he took notice of it, and said, “Gentlemen, by reason of some scoffing that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die by the shaking I have in my hands and knees. I tell you No; but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body, which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves. I have had it this twelve years. I speak this to the praise and glory of God. He hath carried[Pg 206] me above the fear of death, and I value not my life, because I go to my Father, and I am assured I shall take it again. Gentlemen, take notice, that for being an instrument in that cause (an instrument of the Son of God) which hath been pleaded amongst us, and which God hath witnessed to by many appeals and wonderful victories, I am brought to this place to suffer death this day, and if I had ten thousand lives I could freely and cheerfully lay them down all to witness to this matter.”

Then he prayed to himself with tears, and having ended, the hangman pulled down his cap, but he thrust it up and said, “I have one word more to the Lord’s people. Let them not think hardly of any of the good ways of God for all this, for I have found the way of God to be a perfect way, and He hath covered my head many times in the day of battle. By my God I have leaped over a wall, by my God I have run through a troop, and by my God I will go through this death, and He will make it easy to me. Now, into thy hands, O Lord Jesus, I commit my spirit.”

After he was hanged they cut down this true martyr, and stripping him, slashed him open in order to disembowel him. In the last rigour of his agony this staunch soldier is said to have risen up and struck the executioner.

Three days after, Carew and Cook were hanged at the same place, rejoicing and praying cheerfully to the last. As Cook parted from his wife he said to her, “I am going to be married in glory this day. Why weepest thou?—let them weep who part and shall never meet again.”

On the 17th, Thomas Scot perished at the same place. His last words were—“God engaged me in a cause not to be repented of—I say, in a cause not to be repented of.”

Jones and Scrope (both old men) were drawn in one sledge. Their grave yet cheerful and courageous countenances caused great admiration and compassion among the crowd. Observing one of his friend’s children weeping at Newgate, Colonel Jones took her by the hand. He said, “Suppose your father were to-morrow to be King of France, and you were to tarry a little behind, would you weep so?[Pg 207] Why, he is going to reign with the King of kings.” When he saw the sledge, he said, “It is like Elijah’s fiery chariot, only it goes through Fleet Street.” The night before he suffered, he told a friend the only temptation he had was lest he should be too much transported, and so neglect and slight his life, so greatly was he satisfied to die in such a cause. Another friend he grasped in his arms and said, “Farewell! I could wish thee in the same condition as myself, that our souls might mount up to heaven together and share in eternal joys.” To another friend he said, “Ah, dear heart! if we had perished together in that storm going to Ireland, we had been in heaven to welcome honest Harrison and Carew; but we will be content to go after them—we will go after.” It is added that “the executioner, having done his part upon three others that day, was so surfeited with blood and sick, that he sent his boy to finish the tragedy on Colonel Jones.”

Hugh Peters was much afraid while in Newgate lest his spirits should fail him when he saw the gibbet and the fire, but his courage did not fail him in that hour of great need. On his way to execution he looked about and espied a man to whom he gave a piece of gold, having bowed it first, and desired him to carry that as a token to his daughter, and to let her know that her father’s heart was as full of comfort as it could be, and that before the piece should come into her hands he should be with God in glory.

While Cook was being hanged they made Peters sit within the rails to behold his death. While sitting thus, one came to him and upbraided the old preacher with the king’s death, and bade him repent. Peters replied, “Friend, you do not well to trample upon a dying man: you are greatly mistaken—I had nothing to do in the death of the king.”

When Mr. Cook was cut down and about to be quartered, Colonel Turner told the sheriff’s men to bring Mr. Peters nearer to see the body. By and by the hangman came to him, rubbing his bloody hands, and tauntingly asked him, “Come, how do you like this—how do you like this work?”[Pg 208] To whom Mr. Peters calmly replied, “I am not, I thank God, terrified at it—you may do your worst.”

Being upon the ladder, he spoke to the sheriff and said, “Sir, you have here slain one of the servants of God before mine eyes, and have made me to behold it on purpose to terrify and discourage me, but God hath made it an ordinance to me for my strengthening and encouragement.”

When he was going to die, he said, “What, flesh! art thou unwilling to go to God through the fire and jaws of death? Oh! this is a good day. He is come that I have long looked for, and I shall soon be with Him in glory.” And he smiled when he went away. “What Mr. Peters said further it could not be taken, in regard his voice was low at the time and the people uncivil.”

In May 1685 that consummate scoundrel Titus Oates came to the pillory at Charing Cross. He had been condemned to pay a thousand marks fine, to be stripped of his gown, to be whipped from Newgate to Tyburn, from Aldgate to Newgate, and to stand in the pillory at the Royal Exchange and before Westminster Hall. He was also condemned to stand one hour in the pillory at Charing Cross every 10th of August, and there an eye-witness describes seeing him in 1688.[377]

In 1666 and 1667 an Italian puppet-player set up his booth at Charing Cross, and there and then probably introduced “Punch and Judy” into England. He paid a small rent to the overseers of St. Martin’s parish, and is called in their books “Punchinello.” In 1668 we learn that a Mr. Devone erected a small playhouse in the same place.[378]

There is still extant a song written to ridicule the long delay in setting up the king’s statue, and it contains an allusion to “Punch”—

“What can the mistry be, why Charing Cross

These five months continues still blinded with board?

Dear Wheeler, impart—wee are all att a loss,

Unless Punchinello is to be restored.”[379]

[Pg 209]The royal statue at Charing Cross is the work of Hubert Le Sœur, a Frenchman and a pupil of the famous John of Bologna, the sculptor of the “Rape of the Sabines” in the Loggia at Florence. Le Sœur’s copy of the “Fighting Gladiator,” which is praised by Peacham in his “Compleat Gentleman,” once at the head of the canal in St. James’s Park, is now at Hampton Court. Le Sœur also executed the monuments of Sir George Villiers, and Sir Thomas Richardson the judge, in Westminster Abbey.

The original contract for the brazen equestrian statue, a foot larger than life, is dated 1630. The sculptor was to receive £600. The agreement was drawn up by Sir Balthasar Gerbier for the purchaser, the Lord High Treasurer Weston. Yet the existing statue was not cast till 1633, and the above-mentioned agreement speaks of it as to be erected in the Lord Treasurer’s garden at Roehampton; so that the agreement may not refer to the same work, although it certainly specifies that the sculptor shall “take advice of his Maj. riders of greate horses, as well for the shape of the horse and action as for the graceful shape and action of his Maj. figure on the same.”[380]

The present statue was cast in 1633, on a piece of ground near the church in Covent Garden, and not being actually erected when the Civil War broke out, it was sold by the Parliament to John Rivet, a brazier, living at “the Dial, near Holburn Conduit,” with strict orders to break it up. But the man, being a shrewd Royalist, produced some fragments of old brass, and hid the statue underground till the Restoration. Rivet refusing to deliver up the statue after Charles’s return, a replevin was served upon him to compel its surrender. The dispute, however, lasted many years, and he probably pleaded compensation. The statue was erected in its present position about 1674, by an order from the Earl of Danby, afterwards Duke of Leeds. Le Sœur died, it is supposed, before the statue was erected.

Horace Walpole, who praises the “commanding grace[Pg 210] of the figure,” and the “exquisite form of the horse,”[381] incorrectly says, “The statue was made at the expense of the family of Howard, Lord Arundel, who have still the receipt to show by whom and for whom it was cast.”

There is still extant a very rare large sheet print of the statue, engraved in the manner and time of Faithorne, but without name or date. The inscription beneath it describes the statue as almost ten feet high, and as “preserved underground,” with great hazard, charge, and care, by John Rivet, a brazier.[382]

John Rivet may have been a patriot, but he was certainly a shrewd one. To secure his concealed treasure he had manufactured a large quantity of brass handles for knives and forks, and advertised them as being forged from the destroyed statue. They sold well; the Royalists bought them as sad and precious relics; the Puritans as mementos of their triumph. He doubled his prices, and still his shop was crowded with eager customers, so that in a short time he realised a considerable fortune.[383]

The brazier, or the brazier’s family, probably sold the statue to Charles II. at his restoration. The Parliament voted £70,000 for solemnising the funeral of Charles I., and for erecting a monument to his memory.[384] Part of this sum went for the pedestal, but whether the brazier or his kin were rewarded is not known. Charles II. probably spent most of the money on his pleasures.

There is a fatality attending the verses of most time-serving poets. Waller never wrote a court poem well but when he lauded that great man, the Protector. When the statue of “the Martyr” was set up, fourteen years after the Restoration—so tardy was filial affection—Waller wrote the following dull and unworthy lines about the statue of a faithless king:—

[Pg 211]

“That the first Charles does here in triumph ride,

See his son reign where he a martyr died,

And people pay that reverence as they pass

(Which then he wanted) to the sacred brass

Is not th’ effect of gratitude alone,

To which we owe the statue and the stone;

But Heaven this lasting monument has wrought,

That mortals may eternally be taught

Rebellion, though successful, is but vain,

And kings so kill’d rise conquerors again.

This truth the royal image does proclaim

Loud as the trumpet of surviving fame.”

Andrew Marvell, one of the most powerful of lampoon writers, and the very Gillray of political satirists, wrote some bitter lines on the statue of the so-called Martyr at Charing Cross, lines which in an earlier reign would have cost the honest daring poet his ears, if not his head.

There was an equestrian stone statue of Charles II. at Woolchurch (Woolwich?), and the poet imagines the two horses, the one of stone and the other of brass, talking together one evening, when the two riders, weary of sitting all day, had stolen away together for a chat.

“Woolchurch.—To see Dei gratia writ on the throne,

And the king’s wicked life says God there is none.

Charing.—That he should be styled Defender of the Faith

Who believes not a word what the Word of God saith.

Woolchurch.—That the Duke should turn Papist and that church defy

For which his own father a martyr did die.

Charing.—Tho’ he changed his religion, I hope he’s so civil

Not to think his own father has gone to the devil.”

Upon the brazen horse being asked his opinion of the Duke of York, it replies with terrible truth and force:—

“The same that the frogs had of Jupiter’s stork.

With the Turk in his head and the Pope in his heart,

Father Patrick’s disciple will make England smart.

If e’er he be king, I know Britain’s doom:

We must all to the stake or be converts to Rome.

[Pg 212]Ah! Tudor! ah! Tudor! of Stuarts enough.

None ever reigned like old Bess in her ruff.

******

Woolchurch.—But can’st thou devise when kings will be mended?

Charing.—When the reign of the line of the Stuarts is ended.”

In April 1810 the sword, buckles, and straps fell from the statue.[385] The king’s sword was stolen on the day on which Queen Victoria went to open the Royal Exchange.

London has its local traditions as well as the smallest village. There is a foolish story that the sculptor of Charles I. and his steed committed suicide in vexation at having forgotten to put a girth to the horse. The myth has arisen from the supposition of there being no girth, and retailers of such stories, Mr. Leigh Hunt included, did not take the trouble to ascertain whether there was or was not a girth. Unfortunately for the story there is a girth, and it is clearly visible.

The pedestal, by some assigned to Marshal, by others to Grinling Gibbons, the great wood-carver, and a Dutchman by birth, is seventeen feet high, and is enriched with the arms of England, trophies of armour, cupids, and palm-branches. It is erected in the centre of a circular area, thirty feet in diameter, raised one step from the roadway, and enclosed with iron rails. The lion and unicorn are much mutilated, and the trophies are honeycombed and corroded by the weather. It has not been generally observed that on the south side of the pedestal two weeping children support a crown of thorns, and that the same emblem is repeated on the opposite side, below the royal arms.

In 1727 (1st George II.) that infamous rogue, Edmund Curll, the publisher of all the filth and slander of his age, stood in the pillory at Charing Cross for printing a vile work called Venus in a Cloyster. He was not, however, pelted or ill-used; for, with the usual lying and cunning of his reptile nature, he had circulated printed papers telling the people that he stood there for daring to vindicate the[Pg 213] memory of Queen Anne. The mob allowed no one to touch him; and when he was taken down they carried him off in triumph to a neighbouring tavern.[386]

Archenholz, an observant Prussian officer who was in England in 1784, tells a curious anecdote of the statue at Charing Cross. During the war in which General Braddock was defeated by the French in America, about the time when Minorca was in the enemy’s hands, and poor Byng had just fallen a victim to popular fury, an unhappy Spaniard, who did not know a word of English, and had just arrived in England, was surrounded by a mob near Whitehall, who took him by his dress for a French spy. One of the rabble instantly proposed to mount him on the king’s horse. The idea was adopted. A ladder was brought, and the miserable Spaniard was forced upon its back, to be loaded with insults and pelted with mud. Luckily for the stranger, at that moment a cabinet minister happening to pass by, stopped to inquire the cause of the crowd. On addressing the man in French he discovered the mistake, and informed the mob. They instantly helped the man down, and the minister, taking him in his coach to the Spanish ambassador, apologised in the name of the nation for a mistake that might have been fatal.[387]

In June 1731 Japhet Crook, alias Sir Peter Stranger, who had been found guilty of forging the writings to an estate, was sentenced to imprisonment for life.[388] He was condemned to stand for one hour in the pillory at Charing Cross. He was then seated in an elbow-chair; the common hangman cut off both his ears with an incision knife, and then delivered them to Mr. Watson, a sheriff’s officer. He also slit both Crook’s nostrils with a pair of scissors, and seared them with a hot iron, pursuant to the sentence. A surgeon attended on the pillory and instantly applied styptics to prevent the effusion of blood. The man bore the operations with undaunted courage. He laughed on the pillory, and denied the fact to the last. He was then [Pg 214]removed to the Ship Tavern at Charing Cross, and thence taken back to the King’s Bench prison, to be confined there for life.[389]

This Crook had forged the conveyance, to himself, of an estate, upon which he took up several thousand pounds. He was at the same time sued in Chancery for having fraudulently obtained a will and wrongfully gained an estate. In spite of losing his ears, he enjoyed the ill-gained money in prison till the day of his death, and then quietly left it to his executor. He is mentioned by Pope in his 3d epistle, written in 1732. Talking of riches, he says—

“What can they give?—to dying Hopkins heirs?

To Chartres vigour? Japhet nose and ears?”[390]

It was in this essay that, having been accused of attacking the Duke of Chandos, Pope first began to attack vices instead of follies, and, in order to prevent mistakes, boldly to publish the names of the malefactors whom he gibbeted.

Crook had been a brewer on Tower Hill. The 2d George II., c. 25, made forgery a felony; and the first sufferer under the new law was Richard Cooper, a Stepney victualler, who was hanged at Tyburn, in June 1731, six days only after the older and luckier thief had stood in the pillory.

In 1763 Parsons, the parish-clerk of St. Sepulchre’s, and the impudent contriver of the “Cock Lane ghost” deception, mounted here to the same bad eminence. Parsons’s child, a cunning little girl of twelve years, had contrived to tap on her bed in a way that served to convey what were supposed to be supernatural messages. It proved to be a plot devised by Parsons out of malice against a gentleman of Norfolk who had sued him for a debt. This gentleman was a widower, who had taken his wife’s sister as his mistress—a marriage with her being forbidden by law—and had brought her to lodge with Parsons, from whence he had removed her to other lodgings, where she had died suddenly of small-pox. The object of Parsons[Pg 215] was to obtain the ghost’s declaration that she had been poisoned by Parsons’s creditor. The rascal was set three times in the pillory and imprisoned for a year in the King’s Bench. The people, however, singularly enough, did not pelt the impudent rogue, but actually collected money for him.

There is a rare sheet-print of Charing Cross by Sutton Nicholls, in the reign of Queen Anne. It shows about forty small square stone posts surrounding the pedestal of the statue. The spot seems to have been a favourite standing-place for hackney coaches and sedan chairs. Every house has a long stepping-stone for horsemen at a regulated distance from the front.

In 1737 Hogarth published his four prints of the “Times of the Day.”[391] The scene of Night is laid at Charing Cross; it is an illumination-night. Some drunken Freemasons and the Salisbury “High-flyer” coach upset over a street bonfire near the Rummer Tavern, fill up the picture, which is curious as showing the roadway much narrower than it is now, and impeded with projecting signs above and bulkheads below.

The place is still further immortalised in the old song—

“I cry my matches by Charing Cross,

Where sits a black man on a black horse.”

In a sixpenny book for children, published about 1756, the absurd figure of King George impaled on the top of Bloomsbury Church is contrasted with that of King Charles at the Cross.

“No longer stand staring,

My friend, at Cross Charing,

Amidst such a number of people;

For a man on a horse

Is a matter of course,

But look! here’s a king on a steeple.”[392]

It was at Robinson’s coffee-house, at Charing Cross, that that clever scamp, vigorous versifier, and, as I think,[Pg 216] great impostor, Richard Savage, stabbed to death a Mr. Sinclair in a drunken brawl. Savage had come up from Richmond to settle a claim for lodgings, when, meeting two friends, he spent the night in drinking, till it was too late to get a bed. As the three revellers passed Robinson’s, a place of no very good name, they saw a light, knocked at the door, and were admitted. It was a cold, raw, November night; and hearing that the company in the parlour were about to leave, and that there was a fire there, they pushed in and kicked down the table. A quarrel ensued, swords were drawn, and Mr. Sinclair received a mortal wound. The three brawlers then fled, and were discovered lurking in a back-court by the soldiers who came to stop the fray. The three men were taken to the Gate House at Westminster, and the next morning to Newgate. That cruel and bullying judge, Page, hounded on the jury at the trial in the following violent summing up:—“Gentlemen of the jury, you are to consider that Mr. Savage is a very great man, a much greater man than you or I, gentlemen of the jury; that he wears very fine clothes, much finer than you or I, gentlemen of the jury; that he has abundance of money in his pocket, much more money than you or I, gentlemen of the jury; but, gentlemen of the jury, is it not a very hard case, gentlemen of the jury, that Mr. Savage should therefore kill you or me, gentlemen of the jury?”

The verdict was of course “Guilty,” for these homicides during tavern brawls had become frightfully common, and quiet citizens were never sure of their lives. Sentence of death was recorded against him. Eventually a lady at court interceded for the poet, who escaped with six months’ imprisonment in Newgate, which he certainly well deserved.

There is every reason to suppose from the researches of Mr. W. Moy Thomas, that Savage was an impostor. He claimed to be the illegitimate son of the Countess of Macclesfield by Lord Rivers. The lady had an illegitimate child born in Fox Court, Gray’s Inn Lane in 1697; but[Pg 217] this child, there is reason to think, died in 1698.[393] Savage imposed on Dr. Johnson and other friends with stories of being placed at school and apprenticed to a shoemaker in Holborn by his countess mother, until among his nurse’s old letters he one day accidentally discovered the secret of his birth. There is no proof at all of his being persecuted by the countess, whose life he rendered miserable by insults, lampoons, abuse, slander, and begging letters.

Pope has embalmed Page in the Dunciad just as a scorpion is preserved in a spirit-bottle:—

“Morality by her false guardians drawn,

Chicane in furs, and Casuistry in lawn,

Gasps as they straighten at each end the cord,

And dies when Dulness gives her Page the word.”[394]

And again, with equal bitterness and truth, in his Imitations of Horace:—

“Slander or poison dread from Delia’s rage,

Hard words or hanging if your judge be Page.”

This “hanging judge,” who enjoyed his ermine and his infamy till he was eighty, first obtained preferment by writing political pamphlets. He was made a Baron of the Exchequer in 1718, a Justice of the Common Pleas in 1726, and in 1727 transferred to the Court of King’s Bench. Page was so illiterate that he commenced one of his charges to the grand jury of Middlesex with this remarkable statement: “I dare venture to affirm, gentlemen, on my own knowledge, that England never was so happy, both at home and abroad, as it now is.” Horace Walpole mentions that when Crowle, the punning lawyer, was once entering an assize court, some one asked him if Judge Page was not “just behind.” Crowle replied, “I don’t know, but I am sure he never was just before.”[395]

The various mews, now stables, about London, derive their name from the enclosure where falcons in the Middle[Pg 218] Ages were kept to mew (mutare, Minshew) their feathers. The King’s Mews stood on the site of the present Trafalgar Square. In the 13th Edward II. John de la Becke had the custody of the Mews “apud Charing, juxta Westminster.” In the 10th Edward III. John de St. Albans succeeded Becke. In Richard II.’s time the office of king’s falconer, a post of importance, was held by Sir Simon Burley, who was constable of the castles of Windsor, Wigmore, and Guilford, and also of the royal manor of Kennington. This Sir Simon had been selected by the Black Prince as guardian of Richard II., and he also negotiated his marriage. One of the complaints of Wat Tyler and his party was that he had thrown a burgher of Gravesend into Rochester Castle. The Duke of Gloucester had him executed in 1388, in spite of Richard’s queen praying upon her knees for his life. At the end of this reign or in the first year of Henry IV., the poet Chaucer was clerk of the king’s works and also of the Mews at Charing; and here, from his fluttering, angry little feathered subjects, he must have drawn many of those allusions to the brave sport of hawking to be found in the immortal Canterbury Tales.

The falconry continued at Charing till 1534 (26th Henry VIII.), when the king’s fine stabling, with many horses and a great store of hay, being destroyed by fire, the Mews was rebuilt and turned into royal stables, in the reigns of Edward VI. and Mary.[396]

M. St. Antoine, the riding-master, whose portrait Vandyke painted, performed his caracoles and demi-tours at the Mews. Here Cromwell imprisoned Lieut.-Colonel George Joyce, who, when plain cornet, had arrested the king at Holmby. An angry little Puritan pamphlet of four pages, published in 1659, gives an account of Cromwell’s troubles with the fractious Joyce, and how he had resolved to cashier him and destroy his estate.

The colonel was carried by musqueteers to the common Dutch prison at the Mews, and seems to have been much[Pg 219] tormented by Cavalier vermin. There he remained ten days, and was then removed to another close room, where he fell sick from the “evil smells,” and remained so for ten weeks, refusing all the time to lay down his commission, declaring that he had been unworthily dealt with, and that all that had been sworn against him was false.

There was at the Mews gate a celebrated old book shop, opened in 1750 by Mr. Thomas Payne, who kept it alive for forty years. It was the rendezvous of all noblemen and scholars who sought rare books. It may be remarked, by the way, that booksellers’ shops have always been the haunts of wits and poets. Dodsley, the ex-footman, gathered round him the wisest men of his age, as Tonson had also done before him; while, as for John Murray’s back parlour, it was in Byron’s and Moore’s days a very temple of the Muses.

In Charles II.’s time the famous but ugly horse Rowley lived at the Mews, and gave a nickname to his swarthy royal master.

In 1732 that impudent charlatan, Kent, rebuilt the Mews, which was only remarkable after that for sheltering for a time Mr. Cross’s menagerie, when first removed from Exeter Change in 1829.

The National Gallery, one of the poorest buildings in London (which is saying a good deal), was built between 1832 and 1838, from the designs of a certain unfortunate Mr. Wilkins, R.A. It is not often that Fortune is so malicious as to give an inferior artist such ample room to show his inability. The vote for founding the Gallery passed in Parliament in April 1824. The columns of the portico were part of the screen of Carlton House—interesting memorials of a debasing regency, and, if possible, of a worse reign. The site has been called “the finest in Europe:” it is, however, a fine site, which is more than can be said of the building that covers it. The front is 500 feet long. In the centre is a portico, on stilts, with eight Corinthian columns approached by a double flight of steps; a low squat dome not much larger than a washing basin; and two [Pg 220]pepper-castor turrets that crown the eyesore of London. Though on high ground—very high ground for a rather flat city—the architect, pinched for money, contrived to make the building lower than the grand portico of St. Martin’s Church, and even than the houses of Suffolk Place.

One of the last occasions on which William IV. appeared in public was in 1837, before the opening of the first Academy Exhibition here in May. The good-natured king is said to have suggested calling the square “Trafalgar,” and erecting a Nelson monument. A subscription was opened, and the Duke of Buccleuch was appointed chairman.

The square was commenced in 1829, but was not completed till after 1849. The Nelson column was begun in 1837, and the statue set up in November 1843. Three premiums were offered for the three best designs, and Mr. Railton carried off the palm. Upwards of £20,480 were subscribed, and, £12,000 it was thought would be required to complete the monument.[397] It was originally intended to expend only £30,000 upon the whole.[398] Alas for estimates so sanguine, so fallacious! the granite work alone cost upwards of £10,000.

Mr. Railton chose a column, after mature reflection; although triumphal columns are bad art, and the invention of a barbarous people and a corrupt age.[399] He rejected a temple, as too expensive and too much in the way; a group of figures he condemned as not visible at a distance; he finally chose a Corinthian column as new, as harmonious, and as uniting the labours of sculptor and architect.

The column, with its base and pedestal, measures 193 feet. The fluted shaft has a torus of oak leaves. The capital is copied from the fine example of Mars Ultor at Rome; from it rises a circular pedestal wreathed with laurel, and surmounted by a statue of Nelson, eighteen feet high, and formed of two blocks of stone from the Granton quarry. The great pedestal is adorned with four bassi-relievi, eighteen feet square each, representing four of Nelson’s great victories.[Pg 221] It is difficult to say which is tamest of the four. That of “Trafalgar” is by Mr. Carew; the “Nile,” by Mr. Woodington; “St. Vincent,” by Mr. Watson; and “Copenhagen,” by Mr. Ternouth.

The pedestal is raised on a flight of fifteen steps, at the angles of which are placed couchant lions from the designs of Sir Edwin Landseer. They are forged out of French cannon. The capital is of the same costly material, which, considering the brave English blood it has cost, should have been painted crimson. Many years passed by after the commission was given to Sir Edwin Landseer before they were placed in situ.

The cocked hat on Mr. Baily’s statue has been somewhat unjustly ridiculed, and so has the coil of rope or pigtail supporting the hero.

The bronze equestrian statue of George IV., at the north-east end of the square, is by Chantrey. It was ordered by the king in 1829. The price was to be 9000 guineas, but the worthy monarch never paid the sculptor more than a third of that sum; the rest was given by the Woods and Forests out of the national taxes, and the third instalment in 1843, after Chantrey’s death, by the Lords of the Treasury. It is a sprightly and clever statue, but of no great merit. It should have been paid for by William IV., just as the Nelson statue should have been erected by Parliament, the honour being one due to Nelson from an ungrateful nation. This statue of George IV. was originally intended to crown the arch in front of Buckingham Palace—an arch that cost £80,000, and that was hung with gates that cost 3000 guineas. The so-called Chartist riots of 1848 were commenced by boys destroying the hoarding round the base of the Nelson monument.

The fountains in the centre of the Square are of Peterhead granite, and were made at Aberdeen. They are mean, despicable, and unworthy of the noble position which they occupy. Some years ago there was a fuss about an Artesian well that was to feed these stone punch-bowls with inexhaustible gushes of silvery water. This supply has dwindled[Pg 222] down to a sort of overflow of a ginger-beer bottle once a day. I blush when I take a foreigner to see Trafalgar Square, with its squat domes, its mean statues, its tame bassi-relievi, and its disgraceful fountains.

I will not trust myself to criticise the statues of Napier and Havelock. The figures are poor, and unworthy of the fiery soldier and the Christian hero they misrepresent. They should be in the Abbey. Why has the Abbey grown, like the Court, less receptive than ever? What passport is there into the Abbey, where such strange people sleep, if the conquest of Scinde and the relief of Lucknow will not take a body there.

But to return to the National Gallery. Mr. G. Agar-Ellis, afterwards Lord Dover, first proposed a National Gallery in Parliament in 1824; Government having previously purchased thirty-eight pictures from Mr. Angerstein for £57,000. This collection included “The Raising of Lazarus,” by Del Piombo. It is supposed that Michael Angelo, jealous of Raphael’s “Transfiguration,” helped Sebastian in the drawing of his cartoon, which was to be a companion picture for Narbonne Cathedral. It was purchased from the Orleans Gallery for 3500 guineas.[400]

In 1825 some pictures were purchased for the Gallery from Mr. Hamlet. These included the “Bacchus and Ariadne” of Titian, for £5000. This golden picture (extolled by Vasari) was painted about 1514 for the Duke of Ferrara. Titian was then in the full vigour of his thirty-seventh year.[401]

In the same year “La Vierge au Panier” of Correggio was purchased from Mr. Nieuwenhuy, a picture-dealer, for £3800. It is a late picture, and hurt in cleaning. It was one of the gems of the Madrid Gallery.

In 1826, Sir George Beaumont presented sixteen pictures, valued at 7500 guineas. These included one of the finest landscapes of Rubens, “The Chateau,” which originally cost £1500, and Wilkie’s chef-d’œuvre, that fine Raphaelesque composition, “The Blind Fiddler.”

[Pg 223]In 1834 the Rev. William Holwell Carr left the nation thirty-five pictures, including fine specimens of the Caracci, Titian, Luini, Garofalo, Claude, Poussin, and Rubens.

Another important donation was that of the great “Peace and War,” bought for £3000 by the Marquis of Stafford, and given to the nation. It was originally presented to Charles I., by Rubens, who gave unto the king not as a painter but as almost a king.

The British Institution also gave three esteemed pictures by Reynolds, Gainsborough, and West, and a fine Parmigiano.

But the greatest addition to the collection was made in 1834, when £11,500[402] were given for the two great Correggios, the “Ecce Homo” and the “Education of Cupid,” from the Marquis of Londonderry’s collection. To the “Ecce Homo” Pungileoni assigns the date 1520, when the great master was only twenty-six. It once belonged to Murat. The “Education of Cupid,” which once belonged to Charles I., has been a good deal retouched.[403]

In 1836 King William IV. presented to the gallery six pictures; in 1837 Colonel Harvey Ollney gave seventeen; in 1838 Lord Farnborough bequeathed fifteen, and R. Simmons, Esq., fourteen. The last pictures were chiefly of the Netherlands school. In 1854 the nation possessed two hundred and sixteen pictures, and of these seventy only had been purchased.

In 1857 that greatest of all landscape-painters, Joseph M. W. Turner, left the nation 362 oil-paintings, and about 19,000 sketches (including 1757 water-colour drawings of value). In his will this eccentric man particularly desired that two of his pictures—a Dutch coast-scene and “Dido Building Carthage”—should be hung between Claude’s “Sea-Port” and “Mill.”

The will was disputed, and the engravings and the money, all but £20,000, went to the next of kin.

The diploma pictures (that formerly were annually exhibited to the public) are of great interest. They were given[Pg 224] by various members of the Royal Academy at their elections. That of the parsimonious Wilkie—“Boys digging for Rats” (fine as Teniers)—is remarkably small. There is a very fine graceful portrait of Sir William Chambers, the architect, by Reynolds, and one still more robust and glowing of Sir Joshua by himself. He is in his doctor’s robes. There is a splendid but rather pale Etty—“A Satyr surprising a Nymph;” and a fine vigorous picture by Briggs, of “Blood stealing the Crown.”

In 1849, Robert Vernon, Esq., nobly left the nation one hundred and sixty-two fine examples of the English school. These are now removed to the Kensington Museum.

Of the pictures given by Turner to the nation, the masterpieces are the “Téméraire” and the “Escape of Ulysses,”—both triumphs of colour and imagination. The one is a scene from the Odyssey; the other represents an old man-of-war being towed to its last berth—a scene witnessed by the artist himself while boating near Greenwich. The works of Turner may be divided very fairly into three eras: those in which he imitated the Dutch landscape-painters, the period when he copied idealised Nature, and the time when he resorted from eccentricity or indifference to reckless experiments in colour and effect—most of them quite unworthy of his genius. Not in drawing the figure, but in aërial perspective, did Turner excel. The great portfolios of drawings that he left the nation show with what untiring and laborious industry he toiled. In habits sordid and mean, in tastes low and debased, this great genius, the son of a humble hairdresser in Maiden Lane, succeeded in attaining an excellence in landscape, fitful and unequal it is true, but often rising to poetic regions unknown to Claude, Ruysdael, Vandervelde, Salvator, or Backhuysen.

Ever since the modern pictures were removed to South Kensington, there has been a constant effort to transfer the ancient pictures and to abandon the National Gallery to the Royal Academy—a rich society, making £5000 or £6000 a year, which its members cannot spend, and which tenants[Pg 225] the national building only by permission. To remove the pictures from the centre of London is to remove them from those who cannot go far to see them, to the neighbourhood of rich people who do not need their teaching, and who have picture-galleries of their own.

In 1859, twenty pictures were bequeathed to the gallery by Mr. Jacob Bell, and a few years later twenty-two others were added as a gift by Her Majesty. The last great addition is the presentation of ninety-four pictures by Mr. Wynn Ellis. But in spite of all these treasures, acquired by purchase or by bequest, the nation cannot boast that its gallery does justice to our taste or national wealth. It is still lamentably deficient in more than one department; and there are not wanting those who assert that the Royal Academy stifles art rather than promotes it. It is regarded by the outside world as a close-borough, in which the interests of the public and of students are postponed to those of its Associates and Members, the A.R.A.’s and R.A.’s of the age.

The building in which the collection is deposited was erected at the national expense, from the designs of Mr. William Wilkins, R.A., and opened to the public in 1838. It was considerably altered and enlarged in 1860, and in 1869 five other rooms were added by the surrender to the Trustees of those hitherto appropriated by the Royal Academy. In 1876 a new wing was added, after a design by Mr. E. M. Barry, R.A., and the whole collection is now under one roof.

The Royal College of Physicians is a large classic building at the north-west corner of Trafalgar Square. It was built in 1823 from the designs of Sir Robert Smirke. The college was founded in 1518 by Dr. Linacre, the successor to Shakspeare’s Dr. Butts, and physician to Henry VII. From Knightrider Street the doctors moved to Amen Corner, and thence to Warwick Lane, between Newgate Street and Paternoster Row. The number of fellows, originally thirty, is now as unlimited as the “dira cohors” of diseases that the college has to encounter.

In the gallery above the library there are seven preparations[Pg 226] made by the celebrated Harvey when at Padua—“learned Padua.” There are also some excellent portraits—Harvey, by Jansen; Sir Thomas Browne, the author of Religio Medici; Sir Theodore Mayerne, the physician of James I.; Sir Edmund King, who, on his own responsibility, bled Charles II. during a fit; Dr. Sydenham, by Mary Beale; Doctor Radcliffe, William III.’s doctor, by Kneller; Sir Hans Sloane, the founder of the British Museum, by Richardson, whom Hogarth rather unjustly ridiculed; honest Garth (of the “Dispensary”), by Kneller; Dr. Freind, Dr. Mead, Dr. Warren (by Gainsborough); William Hunter, and Dr. Heberden.

There are also some valuable and interesting busts—George IV., by Chantrey (a chef-d’œuvre); Dr. Mead, by the vivacious Roubilliac; Dr. Sydenham, by Wilton; Harvey, by Scheemakers; Dr. Baillie, by Chantrey, from a model by Nollekens; Dr. Babington, by poor Behnes. One of the treasures of the place is Dr. Radcliffe’s gold-headed cane, which was successively carried by Drs. Mead, Askew, Pitcairn, and Baillie. There is also a portrait-picture by Zoffany of Hunter delivering a lecture on anatomy to the Royal Academy. Any fellow can give an order to see this hoarded collection, which should be thrown open to the public on certain days. It is selfish and utterly wanting in public spirit to keep such treasures in the dark.

The wits buzzed about Charing Cross between 1680 and 1730 as thick as bees round May flowers. In this district, between those years, stood “The Elephant,” “The Sugarloaf,” “The Old Man’s Coffee-house,” “The Old Vine,” “The Three Flower de Luces,” “The British Coffee-house,” “The Young Man’s Coffee-house,” and “The Three Queens.”

There is an erroneous tradition that Cromwell had a house on the site of Drummond’s bank. He really lived farther south, in King Street. When the bank was built, the houses were set back full forty yards more to the west, upon an open square place called “Cromwell’s Yard.”[405]

[Pg 227]Drummond’s is said to have gained its fame by advancing money secretly to the Pretender. Upon this being known, the Court withdrew all their deposits. The result was that the Scotch Tory noblemen rallied round the house and brought in so much money that the firm soon became leading bankers, dividing the West End custom with Messrs. Coutts.

Craig’s Court, on the east side of Charing Cross, was built in 1702. It is generally supposed to have been named after the father of Mr. Secretary Craggs, the friend of Pope and Addison: Mr. Cunningham, an excellent and reliable authority, says that as early as the year 1658 there was a James Cragg living on the “water side,” in the Charing Cross division of St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields. The Sun Fire-office was established in this court in 1726; and here is Cox and Greenwood’s, the largest army agency office in Great Britain.

Locket’s, the famous ordinary, so called from Adam Locket, the landlord in 1674, stood on the site of Drummond’s bank. An Edward Locket succeeded to him in 1688, and remained till 1702.[406] In 1693 the second Locket took the Bowling-green House at Putney Heath. That fair, slender, genteel Sir George Etherege, whom Rochester praises for “fancy, sense, judgment, and wit,” frequented Locket’s, and displayed there his courtly foppery, which served as a model for his own Dorimant, and that prince and patriarch of fops Sir Fopling Flutter. Sir George was always gentle and courtly, and was compared in this to Sedley.

He once got into a violent passion at the ordinary, and abused the “drawers” for some neglect. This brought in Mrs. Locket, hot and fuming. “We are so provoked,” said Sir George, “that even I could find it in my heart to pull the nosegay out of your bosom, and fling the flowers in your face.” This mild and courteous threat turned his friends’ anger into a general laugh.

Sir George having run up a long score at Locket’s, added[Pg 228] to the injury by ceasing to frequent the house. Mrs. Locket began to dun and threaten him. He sent word back by the messenger that he would kiss her if she stirred a step in it. When Mrs. Locket heard this, she bridled up, called for her hood and scarf, and told her anxious husband that she’d see if there was any fellow alive who had the impudence! “Prythee, my dear, don’t be so rash,” said her milder husband; “you don’t know what a man may do in his passion.”[407]

Wycherly, that favourite of Charles II. till he married his titled wife, writes in one of his plays (1675), “Why, thou art as shy of my kindness as a Lombard Street alderman of a courtier’s civility at Locket’s.”[408] Shadwell too, Dryden’s surly and clever foe, says (1691), “I’ll answer you in a couple of brimmers of claret at Locket’s at dinner, where I have bespoke an admirable good one.”[409]

A poet of 1697 describes the sparks, dressed by noon hurrying to the Mall, and from thence to Locket’s.[410] Prior proposes to dine at a crown a head on ragouts washed down with champagne; then to go to court; and lastly he says[411]—

“With evening wheels we’ll drive about the Park,

Finish at Locket’s, and reel home i’ the dark.”

In 1708, Vanbrugh makes Lord Foppington doubtful whether he shall return to dinner, as the noble peer says—“As Gad shall judge me I can’t tell, for ’tis possible I may dine with some of our House at Lacket’s.”[412]

And in the same play the very energetic nobleman remarks—“From thence (the Park) I go to dinner at Lacket’s, where you are so nicely and delicately served that, stap my vitals! they shall compose you a dish no bigger than a saucer shall come to fifty shillings. Between eating my dinner and washing my mouth, ladies, I spend my time till I go to the play.”

[Pg 229]In 1709 the epicurean and ill-fated Dr. King, talking of the changes in St. James’s Park, says—

“For Locket’s stands where gardens once did spring,

And wild ducks quack where grasshoppers did sing.”[413]

Tom Brown also mentions Locket’s, for he writes—“We as naturally went from Mann’s Coffee-house to the Parade as a coachman drives from Locket’s to the play-house.”

Prior, the poet, when his father the joiner died, was taken care of by his uncle, who kept the Rummer Tavern at the back of No. 14 Charing Cross, two doors from Locket’s. It was a well-frequented house, and in 1685 the annual feast of the nobility and gentry of St. Martin’s parish was held there. Prior was sent by the honest vintner to study under the great Dr. Busby at Westminster: and in a window-seat at the Rummer the future poet and diplomatist was found reading Horace, according to Bishop Burnet, by the witty Earl of Dorset, who is said to have educated him. Prior, in the dedication of his poems to the earl’s son, proves his patron to have been a paragon. Waller and Sprat consulted Dorset about their writings. Dryden, Congreve, and Addison praised him. He made the court read Hudibras, the town praise Wycherly’s “Plain Dealer,” and Buckingham delay his “Rehearsal” till he knew his opinion. Pope imitated his “Dorinda,” and King Charles took his advice upon Lely’s portraits.

One of Prior’s gayest and pleasantest poems seems to prove, however, that Fleetwood Shepherd was a more essential patron than even the earl. The poet writes—

“Now, as you took me up when little,

Gave me my learning and my vittle,

Asked for me from my lord things fitting,

Kind as I’d been your own begetting,

Confirm what formerly you’ve given,

Nor leave me now at six and seven,

As Sunderland has left Mun Stephen.”

[Pg 230]And again, still more gaily—

“My uncle, rest his soul! when living,

Might have contrived me ways of thriving,

Taught me with cider to replenish

My vats or ebbing tide of Rhenish;

So when for hock I drew pricked white-wine,

Swear’t had the flavour, and was right wine;

Or sent me with ten pounds to Furni-

val’s Inn, to some good rogue attorney,

Where now, by forging deeds and cheating,

I’d found some handsome ways of getting.

All this you made me quit to follow

That sneaking, whey-faced god, Apollo;

Sent me among a fiddling crew

Of folks I’d neither seen nor knew,

Calliope and God knows who,

I add no more invectives to it:

You spoiled the youth to make a poet.”

That rascally housebreaker, Jack Sheppard, made his first step towards the gallows by the robbery of two silver spoons at the Rummer Tavern. This young rogue, whose deeds Mr. Ainsworth has so mischievously recorded, was born in 1701, and ended his short career at Tyburn in 1724.[414] The Rummer Tavern is introduced by Hogarth into his engraving of “Night.” The business was removed to the water side of Charing Cross in 1710, and the new house burnt down in 1750. In 1688, Samuel Prior offered ten guineas reward for the discovery of some persons who had accused him of clipping coin.[415]