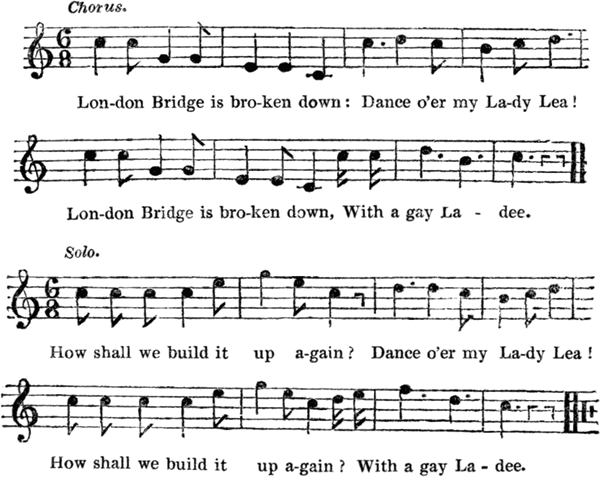

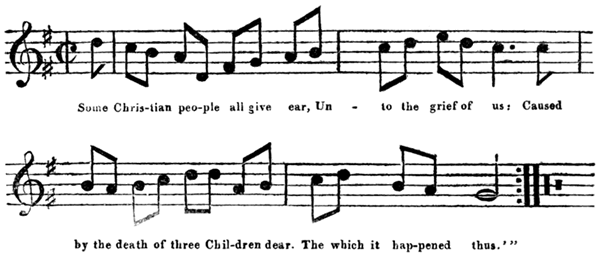

Title: Chronicles of London Bridge Author: Richard Thompson Produced by Veronika Redfern, Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by The Internet Archive (https://archive.org). Music transcribed by Veronika Redfern.

Chronicles

OF

LONDON BRIDGE.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY D. S. MAURICE, FENCHURCH STREET.

TO THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL

JOHN GARRATT, ESQ.

ALDERMAN OF THE WARD OF BRIDGE WITHIN;

WHO, AS

LORD MAYOR OF LONDON,

LAID THE FIRST STONE

OF THE

NEW LONDON BRIDGE,

ON WEDNESDAY, JUNE 15th, 1825;

These Chronicles

ARE MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED.

PREFACE.

The plan of narrative adopted in the ensuing pages, is recommended by both the sanction and the example of very learned antiquity; since, without referring to the numerous classical volumes, which have been written upon the same principle, two of the most ancient and esteemed works on English Jurisprudence have honoured it with their selection. Of the accuracy of the historical events here recorded, the authorities so explicitly cited are the most ample proofs; and, that they might be the more generally interesting, whatever may have been[viii] their original language, the whole are now given in English: so that an argument should lose none of its effect from its too erudite obscurity, nor an illustration any of its amusement by requiring to be translated.

The collection and arrangement of these materials have been a labour so unexpectedly toilsome and extended, as, it is hoped, fully to excuse every delay in the work’s appearance; and, but for the valuable aid of those numerous friends who have so kindly assisted its progress, it must have still been incomplete. Of these, the first and the most fervent has been John Garratt, Esq., who, by a singularly happy coincidence, was at once the founder of the New London Bridge, as Lord Mayor, and a native, and Alderman, of the Ward containing the Old one. Of other benefactors to these sheets, the names of Henry Smedley, Esq.; H. P. Standley, Esq.; Henry Woodthorpe, Esq., Town Clerk; Mr. Joseph York Hatton; Mr. John Thomas Smith, of the British Museum;[ix] Mr. William Upcott, of the London Institution; and Mr. William Knight, of the New Bridge Works; will sufficiently evince the importance of their communications; to whom, as well as to the many other friends, whose kindnesses I am forbidden to enumerate, I thus offer my sincerest acknowledgments. The Historians of the Metropolis have hitherto passed over the subject of this work far too slightingly: it will be my most ample praise to have endeavoured to supply that deficiency, by these

Chronicles of London Bridge.

June 15th, 1827.

DESCRIPTIVE LIST

OF

THE EMBELLISHMENTS.

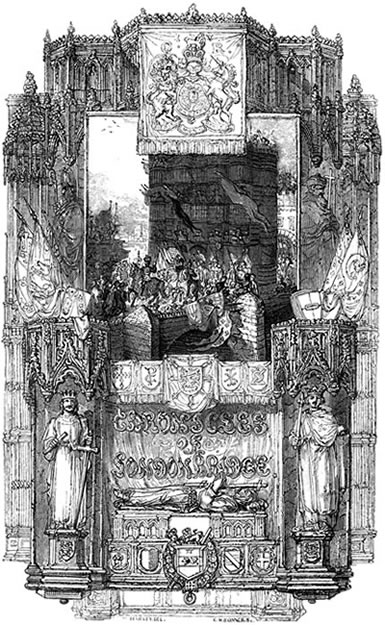

- Historical Title-page, displaying a rich Gothic edifice, surrounded by the Effigies, Armorial Ensigns, &c. of the most eminent persons connected with the history of London Bridge. The two upper figures represent Richard, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Cardinal Hugo di Petraleone, who subscribed so liberally to its original foundation, (see page 61,) and the two lower ones, Kings John and Edward I., commemorative of the Bridge having been finished in the reign of the former, and of the several grants made to it by the latter. In the upper centre is suspended a banner, with the present Royal Arms of England, alluding to the foundation of the New London Bridge in the reign of George IV.; and beneath it, a representation in tapestry, of the triumphal entry of Henry V. across the ancient Bridge, in 1415, after the victory of Agincourt, described on pages 220-229: at the sides of which are groups of banners, &c., commemorative of some of the principal persons engaged in the battle. Below, are the Armorial Ensigns of King Henry II., the Priory of St. Mary Overies, the ancient device of Southwark, and the Monograms of Peter of Colechurch, and Isenbert of Xainctes; the benefactors and Architects of the First Stone Bridge at London. Beneath these is a monumental effigy of Peter of Colechurch; under which appear the ancient and modern Arms of the City of London, see page 177; those of Robert Serle, Mercer, and Custos of London in 1214, the principal citizen to whom the finishing of the Bridge was entrusted, see page 73; those of Henry Walleis, Lord Mayor in 1282, and an eminent benefactor to London Bridge, see pages 131, 132; and in the centre, the shield of John Garratt, Esq., Alderman of the Ward of Bridge-Within, and Lord Mayor in 1824-25, who laid the First Stone of the New Edifice: see pages 635-660.—Designed and Drawn by W. Harvey, from ancient Historical authorities. Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- [xi]Antique Rosette Device on the Title-page, containing the Armorial Ensigns of England, the City of London, the Borough of Southwark, and the Priory of St. Mary Overies. Engraven by the late W. Hughes.

- Dedication Head-piece: An Ornamental Group, consisting of the Armorial Ensigns, &c. of the City of London, the Company of Goldsmiths, and the Right Worshipful John Garratt. Engraven by A. J. Mason.

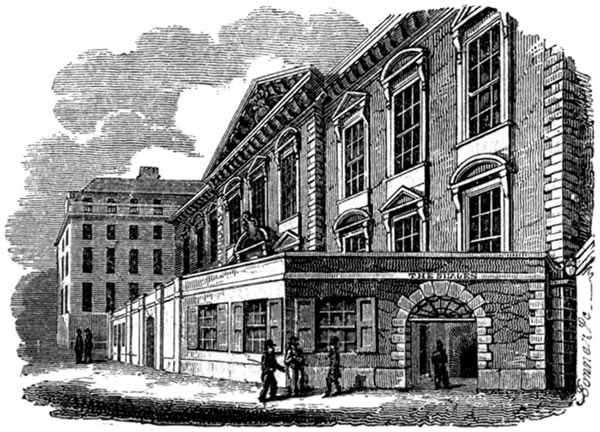

- Page 1. Head-piece: Exterior view of the river-front of Fishmongers’ Hall, with the Shades’ Tavern below it. Drawn and Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Initial Letter: View down Fish-Street-Hill, comprising the Monument, St. Magnus’ Church, and the Northern entrance to London Bridge. Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 39. Ancient Monumental Effigy, from the Church of St. Mary Overies, Southwark; reported to represent John Audery, the Ferryman of the Thames, before the building of London Bridge. Copied from an Etching by Mr. J. T. Smith, Keeper of the Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. Drawn and Engraven by G. W. Moore.

- Page 57. Ancient Water-Quintain, as it was played at upon the River Thames, near London Bridge, in the 12th century: Copied from an Illuminated Manuscript in the Royal Library in the British Museum. Drawn by W. H. Brooke; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 57. Ancient Boat-Tournament of the same period: copied from the same authority. Drawn and Engraven by the same.

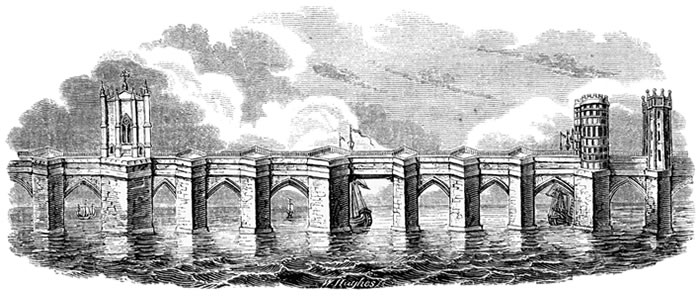

- Page 74. Architectural Elevation of the Centre and Southwark end of the First Stone Bridge erected over the Thames at London, A. D. 1209. Drawn from Vertue’s Prints, and other authorities; Engraven by the late W. Hughes.

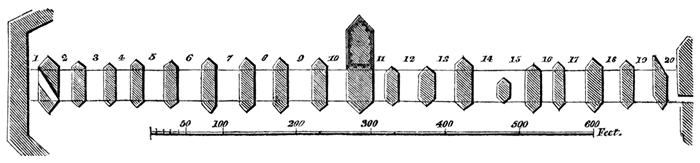

- Page 80. Ground-plan of London Bridge, as first built of Stone by Peter of Colechurch, A. D. 1209. Drawn from the measurements and surveys of Vertue and Hawksmoor; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

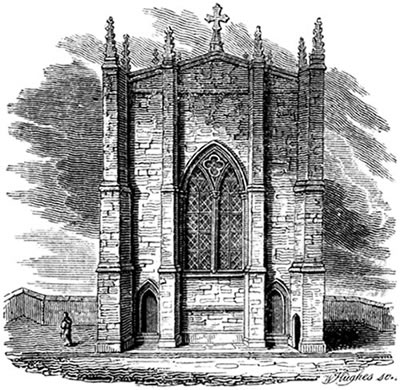

- Page 84. Western Exterior of the Chapel of St. Thomas, on the centre pier of the First Stone London Bridge, A. D. 1209. Drawn from the same authorities, and Engraven by the late W. Hughes.

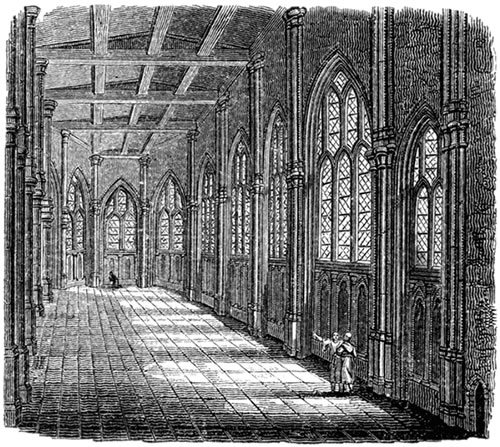

- Page 85. Interior View of the Upper Chapel contained in the above, looking Westward. Drawn from Vertue’s Prints, and Engraven by the late W. Hughes.

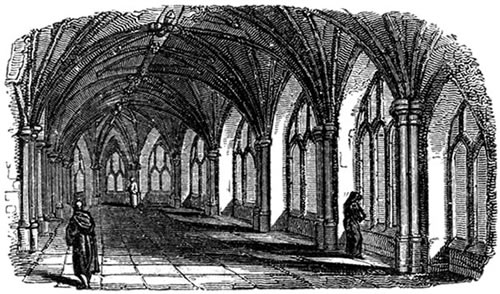

- Page 86. Interior View of the Crypt, or Lower Chapel, contained in the above, looking Eastward. Drawn from the same authorities by W. H. Brooke; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- [xii]Page 87. Southern Series of Windows in ditto. Drawn from the same authorities, and Engraven by the late W. Hughes.

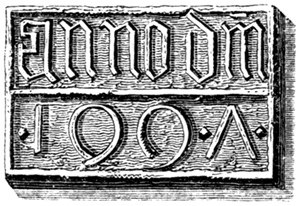

- Page 302. Ancient Date of 1497, carved in stone, found on London Bridge in 1758, and supposed to commemorate a repair done in the former year. Engraven by G. W. Moore.

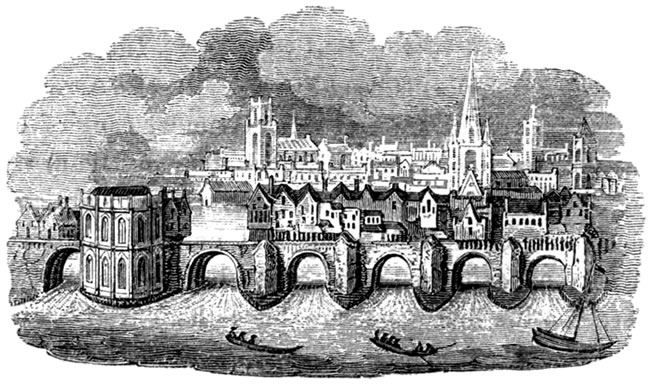

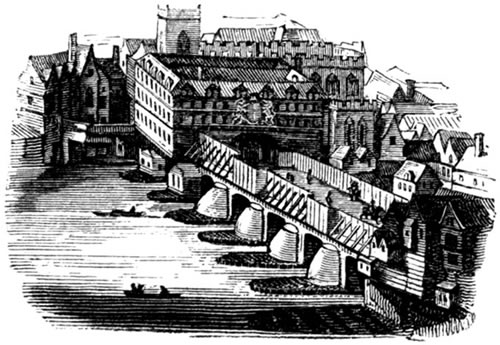

- Page 304. Eastern View of part of London Bridge, as it appeared in the reign of King Henry VII.; shewing the houses, &c. then erected upon it, and the whole depth of the Chapel of St. Thomas. Copied from an Illuminated Manuscript in the Royal Library in the British Museum; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

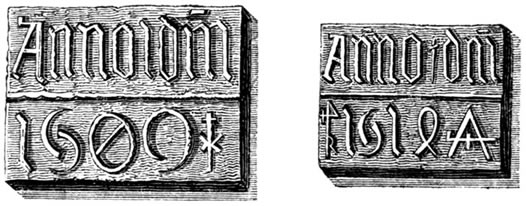

- Page 308. Ancient Dates of 1509 and 1514, carved in stone, and found in 1758 with the former. Engraven by G. W. Moore.

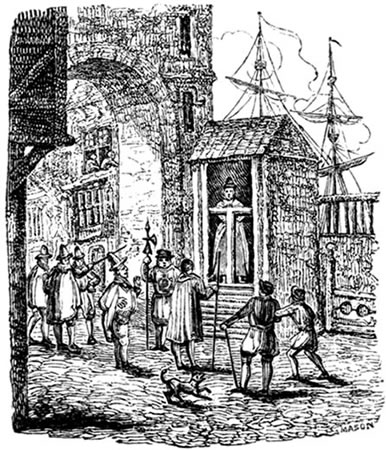

- Page 336. Cage and Stocks on London Bridge, with the confinement of a Protestant Woman, in the reign of Queen Mary. Engraven by A. J. Mason.

- Page 339. Southern View of Traitors’ Gate at the Southwark end of London Bridge, with the heads erected on it in 1579. Drawn from the Venetian copy of Visscher’s View of London, and other authorities; Engraven by H. White.

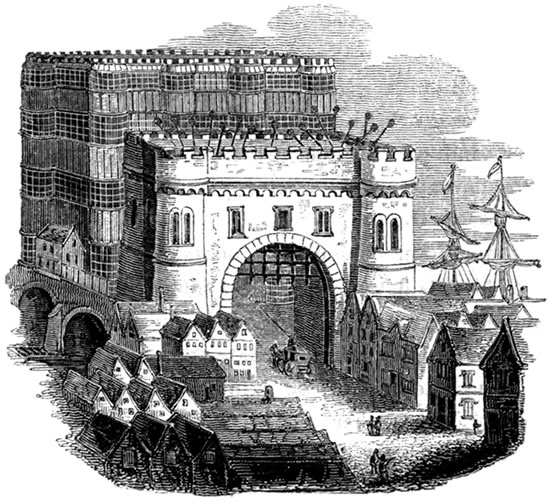

- Page 343. Southern front of the old Southwark Gate and Tower, at the South end of London Bridge, as they appeared in 1647. Drawn from W. Hollar’s Long Antwerp View of London; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

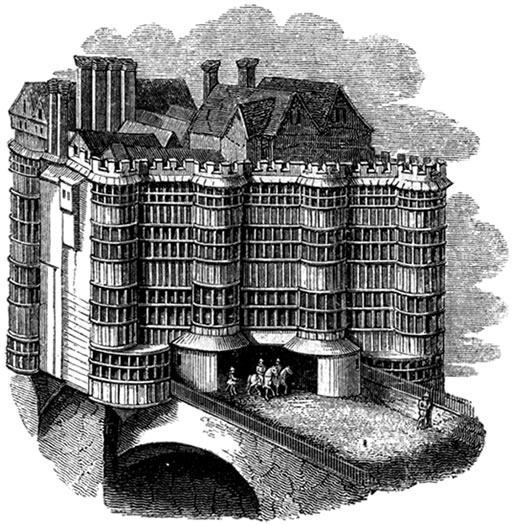

- Page 344. Southern front and Western side of the Nonesuch House and Drawbridge erected on London Bridge, at the above period. Drawn from the same authority; Engraven by T. Mosses.

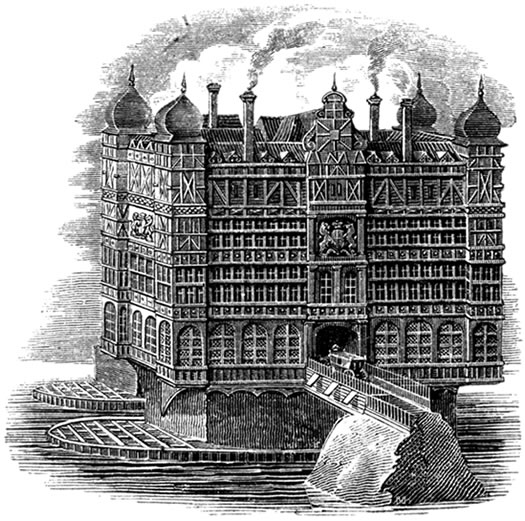

- Page 346. Western side of the Nonesuch House on London Bridge, as it appeared in the time of Queen Elizabeth. Copied from a Tracing of an Original Drawing on vellum, preserved in the Pepysian Library, in Magdalen College, Cambridge; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

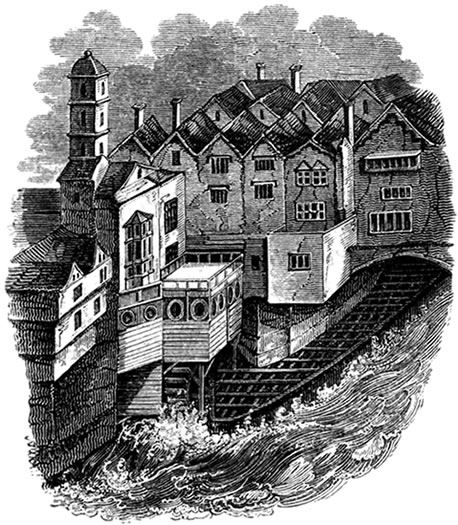

- Page 356. Ancient Corn Mills erected on the Western side of London Bridge, at Southwark. Drawn from the same authority; Engraven by H. White.

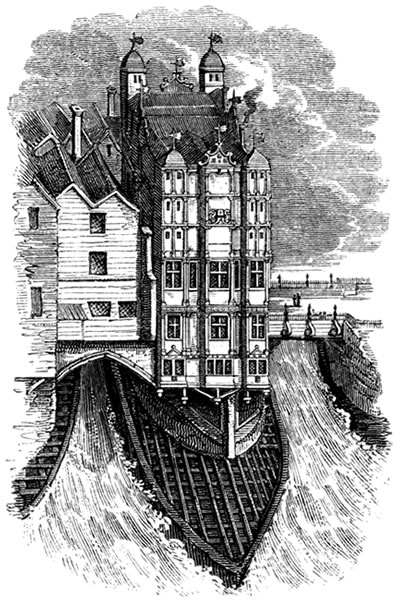

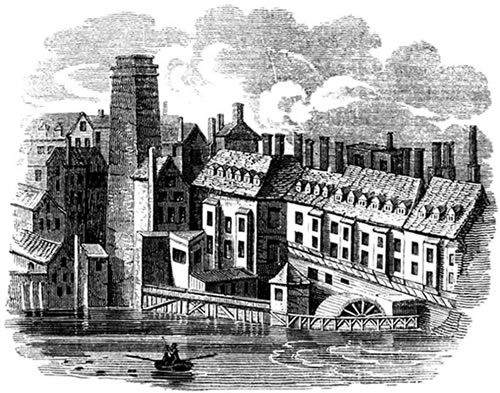

- Page 357. Ancient Water-Works and Water-Tower standing on the Western side of London Bridge, at the North end. Drawn from the same authority; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

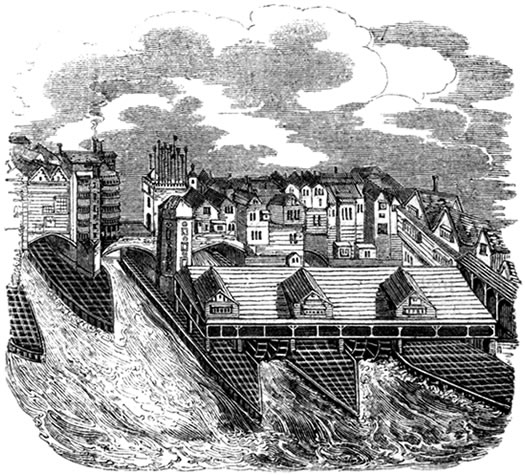

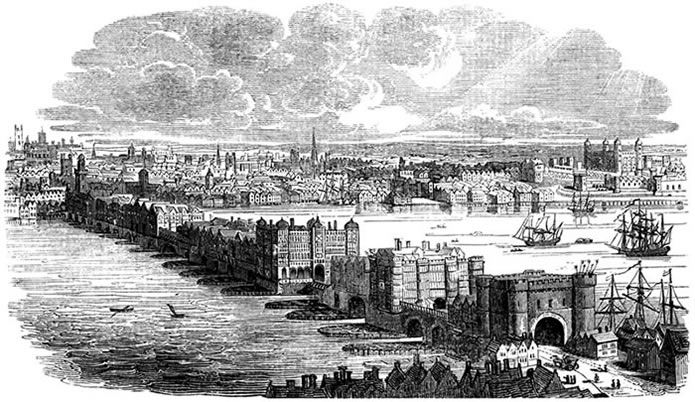

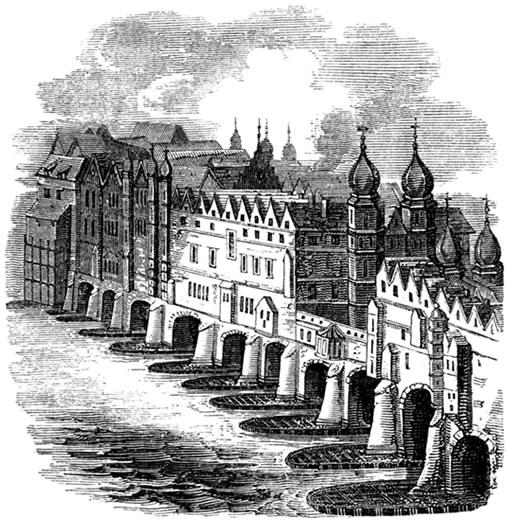

- Page 367. General View of the Western side of London Bridge, with all its ancient buildings, taken from the top of St. Mary Overies’ Church in Southwark, at the close of the Sixteenth Century. Drawn by W. H. Brooke; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- [xiii]Page 384. Copy of a Brass Token, issued by John Welday, living on London Bridge in 1657. Drawn from the Originals in the Collection of the late Barry Roberts, Esq., in the British Museum; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 385. Other Tokens in Brass and Copper, issued by Tradesmen residing at London Bridge. Drawn from the Originals in the British Museum; Engraven by G. W. Moore.

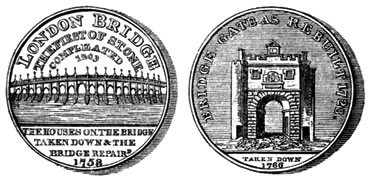

- Page 387. Obverses of Two Medalets struck by P. Kempson, and P. Skidmore, of London Bridge, and Bridge-Gate. Drawn from the Originals, and Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 397. Group of buildings at the Northern end of London Bridge, destroyed in the Fire of 1632-33. Drawn from the Venetian Copy of Visscher’s View of London; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

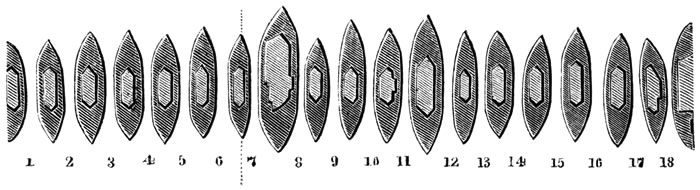

- Page 403. Ground Plan of the Old Stone Bridge of London after the Fire of 1632-33, the extent of which is indicated by the dotted line attached to the seventh sterling from the left hand, or City end, where the Waterhouse was situate. Copied from an Original Drawing on Parchment, preserved in the Print Room of the British Museum; Engraven by G. W. Moore.

- Page 405. Northern end of London Bridge after the Fire of 1632-33, shewing the Old Church of St. Magnus, and the temporary wooden passage erected on the sites of the houses, as it appeared in 1647. Drawn from the Long Antwerp View by Hollar; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 407. View of the same part of London Bridge in the year 1665, before the Great Fire of London, shewing the last wooden passage and King’s Gate, afterwards burned. Copied from a contemporary etching by Hollar; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

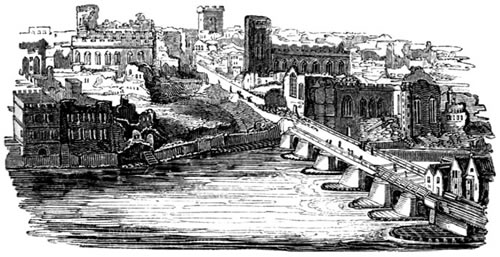

- Page 445. View of the Northern end of London Bridge, and part of the banks of the Thames as they appeared in ruins after the Great Fire of London in 1666. Copied from a contemporary view by W. Hollar; Engraven by H. White.

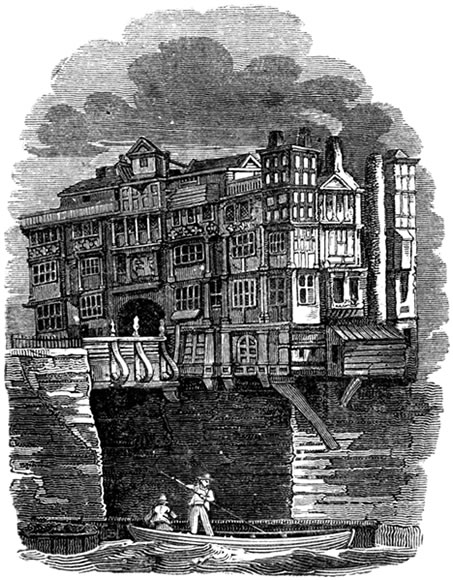

- Page 446. Ancient View of Fishmongers’ Hall from the river, before the Great Fire of London, A. D. 1666. Drawn from the Long Antwerp View, by W. Hollar; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

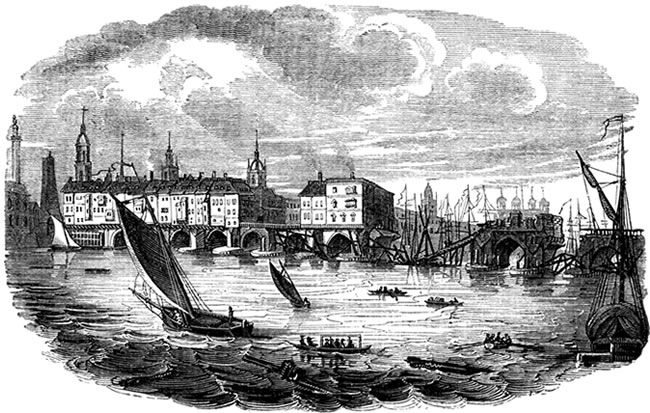

- Page 462. View of the Northern end of London Bridge, with the Water Works and Tower, as they appeared in 1749. Copied from Buck’s View of London; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

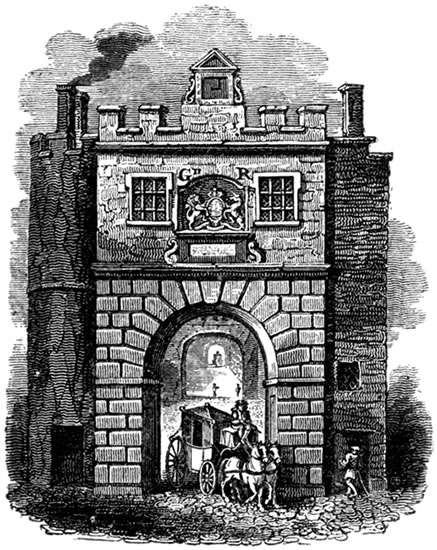

- Page 487. Southern side of Bridge Gate, as rebuilt in 1728. Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

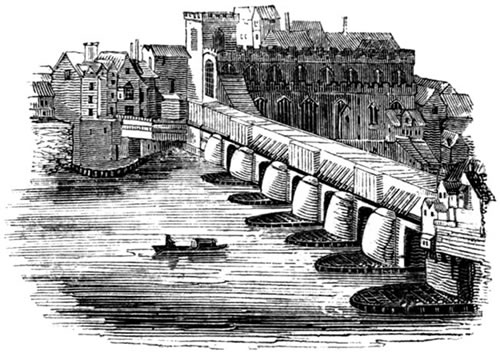

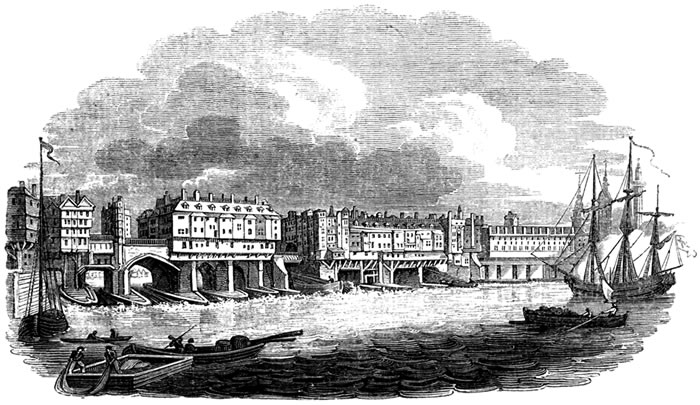

- Page 501. Eastern side of London Bridge before the taking down of the Houses in 1758. Drawn from Scott’s View, taken from St. Olave’s Stairs. Copied by W. H. Brooke; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- [xiv]Page 516. Chapel of St. Thomas on London Bridge, with the adjoining houses, as they appeared at their taking down in 1758. Drawn from a contemporary Etching; Engraven by the late W. Hughes.

- Page 517. Southern front of the Nonesuch House on London Bridge, with the Draw-Bridge, as they appeared in their dilapidated state previously to their taking down in 1758. Drawn from a picture then painted by J. Scott; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 518. Eastern View of the Southwark Gate and Tower on London Bridge, as they appeared previously to their taking down in 1758. Drawn from the same authority; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 521. Northern View of the Temporary Bridge adjoining London Bridge on fire during the night of April 11, 1758. Drawn by W. H. Brooke from an Engraving by Wale and Grignion, with other contemporary authorities; Engraven by H. White.

- Page 526. Western side of London Bridge, shewing the ruins of the Temporary Bridge, and the destruction occasioned by the fire of 1758. Drawn by W. H. Brooke, from the view by A. Walker and W. Herbert; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

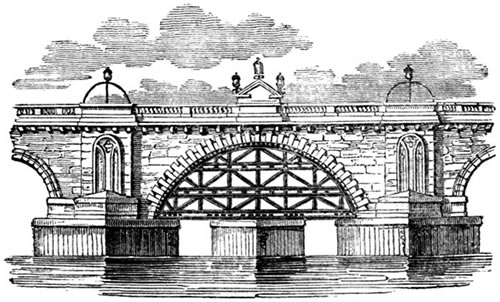

- Page 532. Part of the middle of London Bridge, shewing the wooden Centering upon which the Great Arch was turned, when the Chapel Pier was taken away, and the whole edifice repaired in the year 1759. From a Drawing by Mr. W. Knight; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

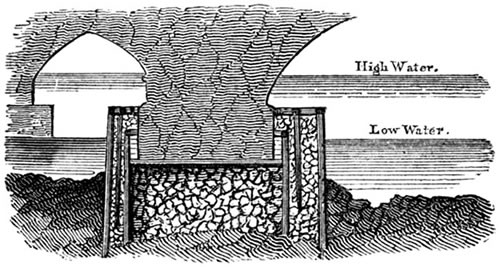

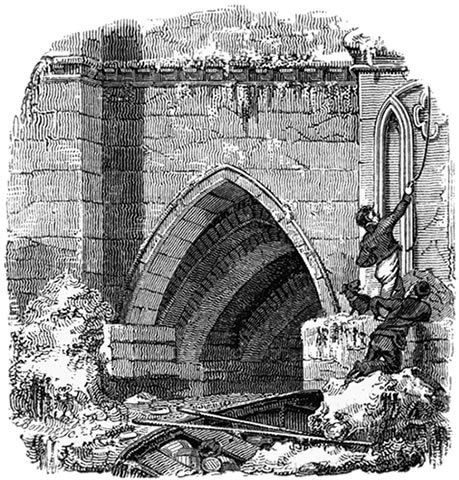

- Page 537. Section of the Northern Pier of the Great Arch of London Bridge, shewing its modern state, and the ancient method of constructing the Piers. From a Drawing by Mr. W. Knight, in August, 1821, when open for examining the foundation. Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

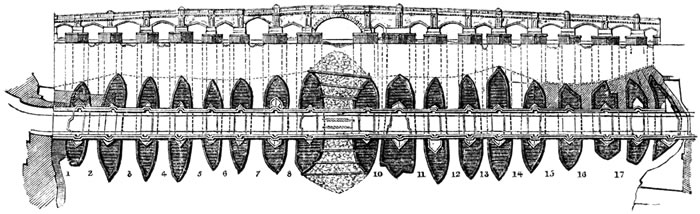

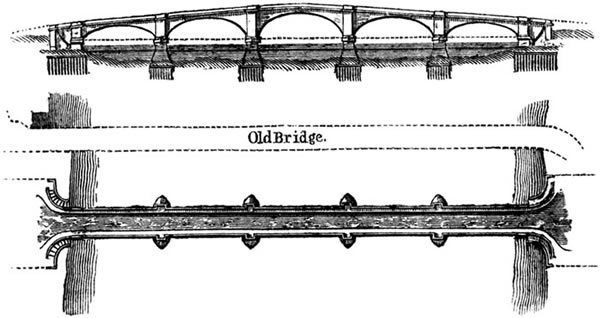

- Page 578. Elevation and Ground-plan of Old London Bridge, shewing the various forms, &c. of the Sterlings, the line of soundings taken along their points, a section of the bed of the River, and the different sizes of the several Locks; with Mr. Smeaton’s method of raising the ground under the great Arch, and the timbers laid down to strengthen it in 1793-94. Reduced from the large survey made by Mr. George Dance in July, 1799, and published with the Second Report on the Improvement of the Port of London. Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

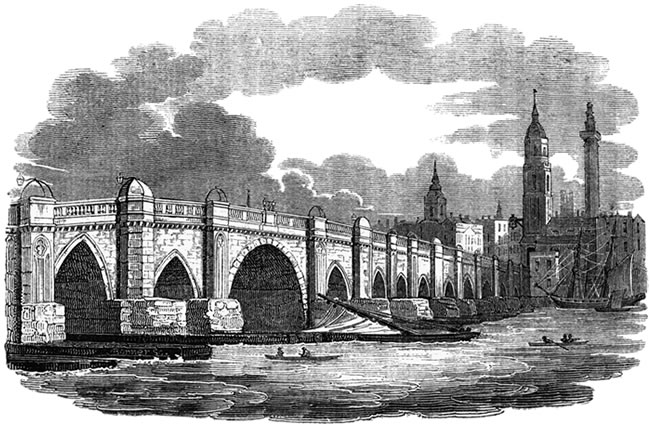

- Page 604. South-Eastern View of London Bridge, A. D. 1825. Drawn and Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 612. Eastern View of the Sixth Arch of London Bridge, from the City end, usually called the Prince’s Lock, as it appeared in the great Frost of 1814; shewing the modern stone casing, with the original building beneath it. Copied by permission from a View taken on the spot and engraved by Mr. J. T. Smith. Drawn and Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- [xv]Page 628. Silver Effigy of Harpocrates, discovered in digging the foundations of the New London Bridge, and presented to the British Museum by Messrs. Rundell, Bridge, and Rundell, November 12, 1825. Drawn from the Original by W. Harvey; Engraven by J. Smith.

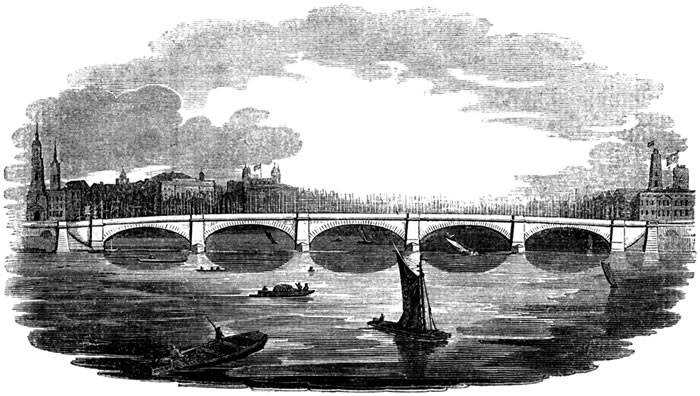

- Page 631. Architectural Elevation and Ground-plan of the New London Bridge, shewing its foundation-piles, and relative situation to the former edifice. From the original authorities. Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

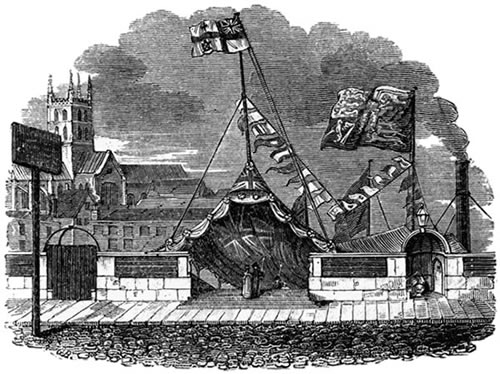

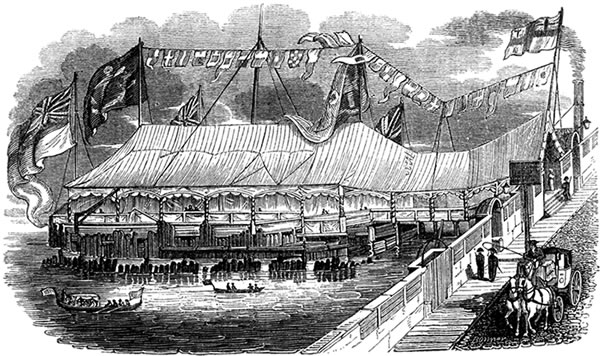

- Page 641. Entrance to the Coffer-Dam from London Bridge, as it appeared decorated for laying the First Stone of the New Bridge on Wednesday, June 15, 1825. Drawn on the spot; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

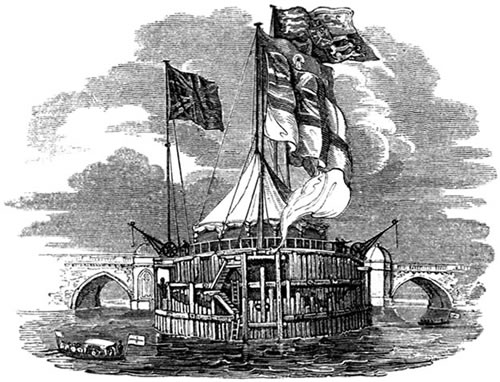

- Page 642. Western end of ditto. Drawn from the River; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 643. General View of the Exterior of ditto. Drawn on the Southern side; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

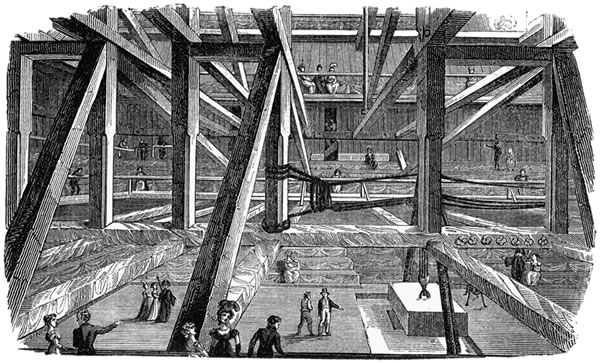

- Page 646. General View of the Interior of ditto, looking Southward; shewing the position of the First Stone, with the cavity beneath it for depositing the Coins, &c. From a Drawing made on the spot; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 651. Representation of the Silver-Gilt Trowel, presented to the Right Honourable John Garratt, for laying the First Stone of the New London Bridge. Drawn from the original; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

- Page 662. Obverse of a Medal struck to commemorate the above ceremony, containing busts of the Lord Mayor and Lady Mayoress. Drawn by W. H. Brooke from the original Model, in the possession of Joseph York Hatton, Esq., executed by Peter Rouw and W. Wyon, Esquires, Modeller and Die-Sinker to His Majesty. Engraven by A. J. Mason.

- Page 664. Western side of the New London Bridge, looking down the River. Drawn by T. Letts; Engraven by G. W. Bonner.

“This is a Gentleman, every inch of him; a Virtuoso, a clean Virtuoso:—a sad-coloured stand of claithes, and a wig like the curled back of a mug-ewe. The very first question he speered was about the auld Draw-Brig, that has been at the bottom of the water these twal-score years. And how the Deevil suld he ken ony thing about the auld Draw-Brig, unless he were a Virtuoso?”

Captain Clutterbuck’s Introductory Epistle to the Monastery.

Chronicles

OF

LONDON BRIDGE.

So numerous are the alterations and modernisms in almost every street of this huge metropolis, that I verily believe, the conservators of our goodly city are trying the strength of a London Antiquary’s heart; and, by their continual spoliations, endeavouring to ascertain whether it be really made “of penetrable stuff.” For my own part, if they continue thus[2] improving, I must even give up the ghost; since, in a little time, there will not be a spot left, where any feature of age will carry back my remembrance to its ancient original. What with pullings-down, and buildings-up; the turning of land into canals, and covering over old water-ways with new paved streets; erecting pert plaister fronts to some venerable old edifices, and utterly abolishing others from off the face of the earth; London but too truly resembles the celebrated keepsake-knife of the sailor, which, for its better preservation, had been twice re-bladed, and was once treated with a new handle. One year carried with it that grand fragment of our city’s wall, which so long girdled-in Moorfields; while another bedevilled the ancient gate of St. John’s Priory with Heraldry, which Belzebub himself could not blazon, and left but one of the original hinges to its antique pier. Nay, there are reports, too, that even Derby House, the fair old College of Heralds,—where my youth was taught “the blasynge of Cote Armures,” under two of the wisest officers that ever wore a tabard,—that even that unassuming quadrangle is to be forthwith levelled with the dust, and thus for ever blotted from the map of London! Alas for the day! Moorgate is not, and Aldgate is not! Aldersgate is but the shadow of a name, and Newgate lives only as the title of a prison-house! In the absence, then, of many an antique building which I yet remember, I have little else to supply the vacuum in my heart, but to wander around the ruins of those few which still[3] exist:—to gaze on the rich transomed bay-windows that even yet light the apartments of Sir Paul Pindar’s now degraded dwelling; to look with regret upon the prostituted Halls of Crosby House; or to roam over to the Bankside, and contemplate the fast-perishing fragments of Winchester’s once proud Episcopal Palace.

It was but recently, in my return from visiting the spot last mentioned, that I betook me to a Tavern where I was erst wont to indulge in another old-fashioned luxury,—which has also been taken away from me,—that of quaffing genuine wine, drawn reaming from the butt in splendid silver jugs, in the merry old Shades by London Bridge. I loved this custom, because it was one of the very few fragments of an ancient Citizen’s conviviality, which have descended to us: a worthy old friend and relative, many a long year since, first introduced me to the goodly practice, and though I originally liked it merely for his sake, yet I very soon learned to admire it for its own. It was a most lovely moonlight night, and I placed myself in one of the window boxes, whence I could see the fastly-ebbing tide glittering with silvery flashes; whilst the broad radiance of the planet, cast upon the pale stone colour of the Bridge, strikingly contrasted with the gas star-like sparks which shone from the lamps above it. “Alas!” murmured I,[4] “pass but another twenty years, and even thou, stately old London Bridge!—even thou shalt live only in memory, and the draughts which are now made of thine image. In modern eyes, indeed, these may seem of little value, but unto Antiquaries, even the rudest resemblance of that which is not, is worth the gold of Ind; and Oh! that we possessed some fair limning of thine early forms; or Oh! for some faithful old Chronicler, who knew thee in all thine ancient pride and splendour, to tell us the interesting story of thy foundation, thine adventures, and thy fate!”

It was at this part of my reverie, that the Waiter at the Shades touched my elbow to inform me, that a stout old gentleman, who called himself Mr. Barnaby Postern, had sent his compliments, and desired the pleasure of my society in the drinking of a hot sack-posset. “My services and thanks,” said I, “wait upon the ancient, I shall be proud of his company: but for sack-posset, where, in the name of Dame Woolley, that all-accomplished cook, hath he learned how to——? but he comes.”

My visitor, as he entered, did not appear any thing very remarkable; he looked simply a shrewd, hale, short old gentleman, of stiff formal manners, wrapped in a dark-coloured cloak, and bearing in his hand a covered tankard, which he set upon the table betwixt us; after which, making a very low bow, he took his seat opposite to me, and at once opened the conversation.

“Your fame,” said he,[5] “Mr. Geoffrey Barbican, as a London Antiquary, is not unknown to me; and I have sometimes pleased myself with the thought, that you must be even a distant relation of my own, since tradition says, that the Barbicans and the Posterns originally received their names from having been gate-keepers in various parts of this fair city: but of that I will not positively speak. Howbeit, I am right glad of this fellowship, because I have some communications and reflections which I would fain make to you, touching the earlier days of that Bridge, under which the tide is now so rapidly running.”

“My dear Mr. Postern,” said I, in rapture, “nothing could delight me more than an Antiquary’s stories of that famous edifice; but moralising I abominate, since I can do that for myself, even to admiration; so, my good friend Mr. Barnaby, as much description, and as many rich old sketches, as you please, but no reflections, my kinsman, no reflections.”

“Well,” returned my visitor, “I will do my best to entertain you; but you very well know, that we old fellows, who have seen generations rise and decay, are apt to make prosing remarks:—However, we’ll start fairly, and taste of my tankard before we set out: trust me, it’s filled with that same beverage, which Sir John Falstaff used to drink o’nights in East Cheap; for the recipé for brewing it was found, written in a very ancient hand upon a piece of vellum, when the Boar’s Head was pulled down many a long year ago. Drink, then, worthy Mr. Barbican; drink, good Sir;—you’ll find it excellent beverage, and I’ll pledge you in kind.”

Upon this invitation, I drank of my visitor’s tankard; and believe me, reader, I never yet tasted any[6] thing half so delicious; for it fully equalled the eulogium which Shakspeare’s jovial knight pronounces upon it in the Second part of “King Henry the Fourth,” Act iv. sc. iii.; where the merry Cavalier of Eastcheap tells us, that “a good Sherris sack hath a two-fold operation in it: it ascends me into the brain, dries me there all the foolish, and dull, and crudy vapours which environ it: makes it apprehensive, quick, forgetive, full of nimble, fiery, and delectable shapes; which, delivered o’er to the voice, (the tongue,) which is the birth, becomes excellent wit. The second property of your excellent Sherris is,—the warming of the blood; which, before cold and settled, left the liver white and pale, which is the badge of pusillanimity and cowardice: but the Sherris warms it, and makes it course from the inwards to the parts extreme. It illumineth the face; which, as a beacon, gives warning to all the rest of this little kingdom, man, to arm; and then, the vital commoners, and inland petty spirits, muster me all to their Captain, the heart; who, great, and puffed up with this retinue, doth any deed of courage; and this valour comes of Sherris: so that skill in the weapon is nothing, without Sack: for that sets it a-work: and learning, a mere hoard of gold kept by a devil, till Sack commences it, and sets it in act and use.—If I had a thousand sons, the first human principle I would teach them, should be,—to forswear thin potations, and addict themselves to Sack!”

Truly, indeed, I felt all those effects in myself;[7] whilst my visitor appeared to be so inspired by it, that, as if all the valuable lore relating to London Bridge had been locked up until this moment, he opened to me such a treasure of information concerning it, that, I verily believe, he left nothing connected with the subject untouched. He quoted books and authors with a facility, to which I have known no parallel; and, what is quite as extraordinary, the same magical philtre enabled me as faithfully to retain them. Indeed, the posset and his discourse seemed to enliven all my faculties in such a manner, that the very scenes of which my companion spake, appeared to rise before my eyes as he described them. When Mr. Postern had pledged me, therefore, by drinking my health, in a very formal manner, he thus commenced his discourse.

“You very well know, my good Mr. Barbican, that Gulielmus Stephanides, or, as the vulgar call him, William Fitz-Stephen, who was the friend and secretary of Thomas à Becket, a native of London, and who died about 1191, in his invaluable tract ‘Descriptio Nobilissimæ Civitatis Londoniæ,’ folio 26, tells us that to the North of London, there existed, in his days, the large remains of that immense forest which once covered the very banks of this brave river. ‘Proxime patet ingens foresta,’ &c. begins the passage; and pray observe that I quote from the best edition with a commentary by that excellent Antiquary Dr. Samuel Pegge, published in London, in the year 1772, in quarto. Ever, Mr. Barbican, while you live, ever quote from the[8] editio optima of every author whom you cite; for, next to a knowledge of books themselves, is an acquaintance with the best editions. But to return, Sir; in those woody groves of yew, which the old citizens wisely encouraged for the making of their bows, were then hunted the stag, the buck, and the doe; and the great Northern road, which now echoes the tuneful Kent bugle of mail-coach-guards, was then an extensive wilderness, resounding with the shrill horns of the Saxon Chiefs, as they waked up the deer from his lair of vert and brushwood. The very paths, too, that now behold the herds of oxen and swine driven town-ward to support London’s hungry thousands, then echoed with the bellowing of savage bulls, and the harsh grunting of many a stout wild boar. But, as you have observed, I am to describe scenes, and you are to moralise upon their changes, so we’ll hasten down again to the water-side, only observing, that the site of the ancient British London is yet certainly marked out to you, by the old rhyming stone in Pannier Alley, by St. Paul’s, which saith:—

THE CITY ROVND,

YET STILL THIS IS

THE HIGHEST GROVND.’

“Now, Julius Cæsar tells you in his Commentaries ‘De Bello Gallico,’ lib. v. cap. xxi. that ‘a British town was nothing more than a thick wood, fortified with a ditch and rampart, to serve as a place of retreat against the incursions of their enemies.’ Here, then, stood our[9] good old city, upon the best ’vantage ground of the Forest of Middlesex; the small hive-shaped dwellings of the Britons, formed of bark, or boughs, or reeds from the rushy sides of these broad waters, being interspersed between the trees; whilst their little mountain metropolis, the ‘locum reperit egregiè naturâ, atque opere munitum,’ a place which appeared extremely strong, both by art and nature,—as the same matchless classic called those primitive defences,—was guarded on the North by a dark wood, that might have daunted even the Roman Cohorts; and to the South, where there was no wilderness, morasses, covered with fat weeds, and divided by such streams as the Wall-brook, the Shareburn, the Fleta, and others of less note, stretched downward to the Thames. As Cæsar and his Legions marched straight from the coast, worthy old Bagford was certainly in the right, when, in a letter to his brother-antiquary Hearne, he said, that the Roman invader came along the rich marshy ground now supporting Kent Street,—in truth very unlike the road of a splendid conqueror,—and, entering the Thames as the tide was just turning, his army made a wide angle, and was driven on shore by the current close to yonder Cement Wharf, at Dowgate Dock. This you find prefixed to Tom Hearne’s edition of Leland’s ‘Collectanea de Rebus Britannicis,’ London, 1774, 8vo., volume i. pp. lviii. lix.: and many an honest man, since ‘the hook-nosed fellow of Rome,’ before a bridge carried him over the waters dry-shod, has tried the same route, in preference to going up to the Mill-ford, in the Strand,[10] or York-ford which lay still higher. In good time, however, the Romans, to commemorate their own successful landing there, built a Trajectus, or Ferry, to convey passengers to their famous military road which led to Dover. But history is not wholly without the mention of a Bridge over the Thames near London, even still earlier than this period; for, when Dion Cassius is recording the invasion of Britain by the Emperor Claudius I., A. D. 44, he says,—‘The Britons having betaken themselves to the River Thames, where it discharges itself into the Sea, easily passed over it, being perfectly acquainted with its depths and shallows: while the Romans, pursuing them, were thereby brought into great danger. The Gauls, however, again setting sail, and some of them having passed over by the Bridge, higher up the River, they set upon the Britons on all sides with great slaughter; until, rashly pursuing those that escaped, many of them perished in the bogs and marshes.’ This passage, which it must be owned, however, is not very satisfactory, is to be found in the best edition of the ‘Historiæ Romanæ,’ by Fabricius and Reimar, Hamburgh, 1750-52, folio, volume ii. page 958; in the 60th Book and 20th Section. The Greek text begins, ‘Ἀναχωρησάντων δ’ ἐντεῦθεν τῶν Βρεττανῶν ἐπὶ τὸν Ταμέσαν ποταμὸν,’ &c.; and the Latin—‘Inde se Britanni ad fluvium Tamesin.’ I have only to remind you that Dion Cassius flourished about A. D. 230. Before we finally quit Roman London, however, I must make one more historical remark. The inscription on the monument[11] which I quoted from Pannier Alley, is dated August the 27th, 1688; and if even at that period,—through all the mutations of the soil, and more than sixteen centuries after the Roman Invasion,—the ground still retained its original altitude, it yet further proves on how admirable a site our ancient London was originally erected:—well worthy, indeed, to be the metropolis of the world. This also is remarked by honest Bagford, in his work already cited, where, at page lxxii., he says,—‘For many of our ancient kings and nobility took delight in the situation of the old Roman buildings, which were always very fine and pleasant, the Romans being very circumspect in regard to their settlements, having always an eye to some river, spring, wood, &c. for the convenience of life, particularly an wholesome air. And this no doubt occasioned the old Monks, Knights Templars, and, after them, the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, as also the Friars, to settle in most of the Roman buildings, as well private as public, which thing, if duly considered, will be found to be a main reason why we have so few remains of them.’

“As I have always considered that the Romans had no more to do with Britain, than Joe the waiter here would have in a Conclave of Cardinals, I will not trouble you with any sketch of the dress or manners of the ferryman and his customers, during their government. Indeed, as a native of London, I always lament over it as the time of our captivity; and so I shall hasten on to the tenth century, when our Runic[12] Ancestors from Gothland were settled in Britain;—when courage was the chiefest virtue, and the rudest hospitality——”

“Have pity upon me, my excellent Mr. Postern,” interrupted I, “for I am naturally impatient at reflections; if you love me, then, give me scenery without meditations, and history without a moral.”

“Truly, Sir,” said he, “I was oblivious, for I’d got upon a favourite topic of mine, the worth of our Saxon fore-fathers; but we’ll cut them off short by another draught of the sack-posset, and take up again with the establishment of a ferry by one Master Audery, in the year nine hundred and ninety——Ah! see now, my memory has left me for the precise year, but nevertheless, Mr. Geoffrey Barbican, my service to you.” When he had passed me the tankard, after what I considered a very reasonable draught, Mr. Postern thus continued.

“I hold it right, my friend, to mix these convivialia with our antiquarian discussions, because I know that they are not only ancient, but in a manner peculiar to this part of the water-side; for we find Stephanides, Stephanus ab Stephano, as I may jocularly call him, whom I before quoted, saying at folio 32, ‘Præterea est in Londonia super ripam fluminis,’ &c. but we’ll give the quotation in plain English. ‘And moreover, on the banks of the river, besides the wine sold in ships’—that is to say, foreign wines of Anjou, Auxere, and Gascoigne, though even then we had some Saxon and Rhenish wines well worth the[13] drinking,—‘besides the wines sold in ships and vaults, there is a public eating-house, or cook’s shop. Here, according to the season, you may find victuals of all kinds, roasted, baked, fried, or boiled. Fish, large and small, with coarse viands for the poorer sort, and more delicate ones for the rich, such as venison, fowls, and small birds. In case a friend should arrive at a Citizen’s house, much wearied with his journey, and chuses not to wait, an-hungered as he is, for the buying and cooking of meat,

The water’s served, the bread’s in baskets brought,

Virg. Æn. i. 705.

and recourse is immediately had to the bank above-mentioned, where every thing desirable is instantly procured. No number so great, of knights or strangers, can either enter the city at any hour of day or night, or leave it, but all may be supplied with provisions, so that those have no occasion to fast too long, nor these to depart the city without their dinner. To this place, if they be so disposed, they resort, and there they regale themselves, every man according to his abilities. Those who have a mind to indulge, need not to hanker after sturgeon, nor a guinea-fowl, nor a gelinote de bois,’—which some call red-game, and others a godwit—[14]‘for there are delicacies enough to gratify their palates. It is a public eating-house, and is both highly convenient and useful to the city, and is a clear proof of its civilization.’

“Thus speaks Fitz-Stephen of the time of Henry II. between the years 1170 and 1182; and if you look but two centuries later, you shall find that John Holland, Duke of Exeter, held his Inn here at Cold Harbour, and gave to his half-brother, King Richard the Second, a sumptuous dinner, in 1397. Then too, when this spot became the property of the merry Henry Plantagenet, Prince of Wales, by the gift of Henry the Fourth, the same King filled his cellars with ‘twenty casks and one pipe of red wine of Gascoigne, free of duty.’ This you have on the authority of John Stow, on the one part, in his ‘Survey of London,’ the best edition by John Strype, &c. London, 1754, folio, volume i. page 523; and of Master Thomas Pennant, on the other, in his ‘Account of London,’ 2nd edition, London, 1791, 4to, page 330.”

“Aye, Master Postern,” said I, “and that same Cold Harbour is not the less dear to me, forasmuch as Stow noteth, in the very place which you have just now cited, that Richard the Third gave the Messuage, and all its appurtenances, to John Wrythe, Garter Principal King of Arms, and the rest of the Royal Heralds and Pursuivants, in 1485.”—“True, Mr. Geoffrey, true,” answered my visitor; “and you may remember that here also, in these very Shades, did King Charles the merry, regale incognito; and here, too, came Addison and his galaxy of wits to finish a social evening. Then, but a little above to the North, was the famous market of East Cheap; of which our own Stow speaks in his book before cited, page 503, quoting the very rare ballad of ‘London Lickpenny,’ composed by Dan[15] John Lydgate, of which a copy in the old chronicler’s own hand writing, is yet extant in the Harleian Manuscripts, No. 542, article 17, folio 102, of which stanza 12 says,—

One cried ribes of befe, and many a pie,

Pewtar potts they clatteryd on a heape,

Ther was harpe, pipe, and sawtry,

Ye by cokke, nay by cokke, some began to cry,

Some sange of Jenken and Julian, to get themselves mede;

Full fayne I wold hade of that mynstralsie

But for lacke of money I cowld not spede!’

“Lydgate, you know, died in the year 1440, at the age of sixty. In the present day, indeed, we have only the indications of this festivity in the names of the ways leading down to, or not far from, the river; as, Pudding Lane, Fish Street Hill, the Vine-tree, or Vintry, Bread-street,——”

“Hold! hold! my dear Mr. Barnaby,” interrupted I, “what on earth has all this long muster-roll of gluttony to do with London Bridge? You are, as it were, endeavouring to prove, that yonder is the moon lighting the waters; for certes, it is a self-evident truth, that the citizens of London have from time immemorial been mighty trencher-men; nay, if I remember me rightly, your own favourite Stephanides says, ‘The only plagues of London are, immoderate drinking of idle fellows, and often fires:’ so that we’ll take for granted, and get on to the Bridge.”

“You are in the right,” answered Mr. Postern;[16] “the passage begins ‘Solæ pestes Londoniæ,’ &c. at folio 42, and truly I wished but to shew you how proper a place these Shades are to be convivial in; but now we will but just touch upon the Saxon Ferry and Wooden Bridge, and then come at once to the first stone one, founded by the excellent Peter of Colechurch, in the year 1176. I would you could but have seen the curious boat in which, for many years, Audery the Ship-wight, as the Saxons called him, rowed his fare over those restless waters. It was in form very much like a crescent laid upon its back, only the sharp horns turned over into a kind of scroll; and when it was launched, if the passengers did not trim the barque truly, there was some little danger of its tilting over, for it was only the very centre of the keel that touched the water. But our shipman had also another wherry, for extra passengers, and that had the appearance of a blanket gathered up at each end, whilst those within looked as if they were about to be tossed in it. His oars were in the shape of shovels, or an ace of spades stuck on the end of a yard measure; though one of them rather seemed as if he were rowing with an arrow, having the barb broken off, and the flight held downwards. It is nearly certain, that at this period there was no barrier across the Thames; for you may remember how the ‘Saxon Chronicle,’ sub anno 993, tells you that the Dane Olaf, Anlaf, or Unlaf, ‘mid thrym et hundnigentigon scipum to Stane,’—which is to say, that[17] ‘he sailed with three hundred and ninety ships to Staines, which he plundered without, and thence went to Sandwich.’

“Before I leave speaking of this King Olaf, however, I wish you to observe the paction which he made with the English King Ethelred, for we shall find him hereafter closely connected with the history of London Bridge. The same authority, and under the same year and page, tells you that, after gaining the battle of Maldon, and the death of Alderman Britnoth, peace was made with Anlaf, ‘and the King received him at Episcopal hands, by the advice of Siric, Bishop of Canterbury, and Elfeah of Winchester.’ On page 171, in the year 994, you also find this peace more solemnly confirmed in the following passage. ‘Then sent the King after King Anlaf, Bishop Elfeah, and Alderman Ethelwerd, and hostages being left with the ships, they led Anlaf with great pomp to the King, at Andover. And King Ethelred received him at Episcopal hands, and honoured him with royal presents. In return Anlaf promised, as he also performed, that he never again would come in a hostile manner to England.’ I quote, as usual, from the best edition of this invaluable record by Professor Ingram, London, 1823, 4to. It is generally believed, however, that the year following Anlaf’s invasion, namely 994, there was built a low Wooden Bridge, which crossed the Thames at St. Botolph’s Wharf yonder, where the French passage vessels are now lying; and a rude thing enough it was, I’ll warrant; built of thick rough-hewn timber planks, placed upon piles, with moveable[18] platforms to allow the Saxon vessels to pass through it Westward. A Bridge of any kind is not so small a concern but what one might suppose you could avoid running against it, and yet William of Malmesbury, the Benedictine Monk, who lived in the reign of King Stephen, and died in 1142, says, that, in 994, King Sweyn of Denmark, the Invader, ran foul of it with his Fleet. This you find mentioned in his book, ‘De Gestis Regum Anglorum,’ the best edition, London, 1596, folio:—though, by the way, the preferable one is called the Frankfurt reprint of 1601, as it contains all the errata of the London text, and adds a good many more of its own; for I am much of the mind of Bishop Nicolson, and Sir Henry Spelman, who observe that the Germans committed abundance of faults with the English words. In this record, which is contained in Sir Henry Savile’s ‘Rerum Anglicarum Scriptores Post Bedam,’ of the foregoing date and size, at folio 38b, is the passage beginning ‘Mox ad Australes regiones,’ &c. of which this is the purport.

“‘Some time after, the Southern parts, with the inhabitants of Oxford and Winchester, were brought to honour his’—that is to say King Sweyn’s—‘laws: the Citizens of London alone, with their lawful King’—Ethelred the Second—[19]‘betook themselves within the walls, having securely closed the gates. Against their ferocious assailants, the Danes, they were supported by their virtue, and the hope of glory. The Citizens rushed forward even to death for their liberty; for none could think himself secure of the future if the King were deserted, in whose life he committed his own: so that although the conflict was valiant on both sides, yet the Citizens had the victory from the justness of their cause; every one endeavouring to shew, throughout this great work, how sweet he estimated those pains which he bore for him. The enemy was partly overthrown; and part was destroyed in the River Thames, over which, in their precipitation and fury, they never looked for the Bridge.’

“I know very well that the truth of this circumstance is much questioned by Master Maitland, at page 43 of his ‘History of London,’ continued by the Rev. John Entick, London, 1772, folio, volume i.; wherein he denies that any historian mentions a Bridge at London, in the incursion of Anlaf or Sweyn; and asserts that the loss of the army of the latter was occasioned ‘by his attempting to pass the River, without enquiring after Ford, or Bridge.’ He affirms too, that Stow mistakes the account given by William of Malmesbury; and that the Monk himself distorts his original authority in saying that the invaders had not a regard to the Bridge. Now, if, as the margin of Maitland’s History states, the Saxon Chronicle were that authority, the Library-keeper of Malmesbury had no greater right to speak as Maitland does, than he had for using those words which I have already translated,—‘part were destroyed in the River Thames, over which, in their precipitation and fury, they never looked for the Bridge:’ for the words of the[20] Saxon Chronicle, at page 170, are, in reality,—‘And they closely besieged the City and would fain have set it on fire, but they sustained more harm and evil than they ever supposed that the Citizens could inflict on them. The Holy Mother of God’—for the Invasion took place on her Nativity, September the 8th,—‘on that day considered the Citizens, and ridded them of their enemies.’ Here then is no word of a Bridge, nor, indeed, does any Historian record the event as William of Malmesbury does. Lambarde—whom I shall quote anon,—when he relates it, cites the ‘Chronicle of Peterborough,’ and the ‘Annals of Margan,’ but neither of them have the word Bridge upon their pages. He, most probably, took this circumstance from Marianus Scotus, a Monk of Mentz, in Germany, who wrote an extensive History of England and Europe ending in 1083, but, of this, only the German part has been printed, although it was amazingly popular in manuscript.

“We have, however, an earlier description of London Bridge in a state of warlike splendour, than is commonly imagined, or at least referred to, by most Antiquaries; and that too from a source of no inconsiderable authority: for the learned old Icelander Snorro Sturlesonius, who wrote in the 13th century, and who was assassinated in 1241, on page 90 of that rather rare work by the Rev. James Johnstone, entitled ‘Antiquitates Celto-Scandicæ,’ Copenhagen, 1786, quarto, gives the following very interesting particulars of the Battle of Southwark, which took place[21] in the year 1008, in the unhappy reign of Ethelred II., surnamed the Unready.

“‘They’—that is the Danish forces—‘first came to shore at London, where their ships were to remain, and the City was taken by the Danes. Upon the other side of the River, is situate a great market called Southwark,’—Sudurvirke in the original—‘which the Danes fortified with many defences; framing, for instance, a high and broad ditch, having a pile or rampart within it, formed of wood, stone, and turf, with a large garrison placed there to strengthen it. This, the King Ethelred,’—his name, you know, is Adalradr in the original,—‘attacked and forcibly fought against; but by the resistance of the Danes it proved but a vain endeavour. There was, at that time, a Bridge erected over the River between the City and Southwark, so wide, that if two carriages met they could pass each other. At the sides of the Bridge, at those parts which looked upon the River, were erected Ramparts and Castles that were defended on the top by penthouse-bulwarks and sheltered turrets, covering to the breast those who were fighting in them: the Bridge itself was also sustained by piles which were fixed in the bed of the River. An attack therefore being made, the forces occupying the Bridge fully defended it. King Ethelred being thereby enraged, yet anxiously desirous of finding out some means by which he might gain the Bridge, at once assembled the Chiefs of the army to a conference on the best method of destroying it. Upon this, King[22] Olaf engaged,’—for you will remember he was an ally of Ethelred,—‘that if the Chiefs of the army would support him with their forces, he would make an attack upon it with his ships. It being ordained then in council, that the army should be marched against the Bridge, each one made himself ready for a simultaneous movement both of the ships and of the land forces.’

“I must here entreat your patience, Mr. Geoffrey Barbican, to follow the old Norwegian through the consequent battle; for although he gives us no more scenery of London Bridge, yet he furnishes us with a minute account of its destruction, and of a conflict upon it, concerning which all our own historians are, in general, remarkably silent. I say too, with Falstaff, ‘play out the play;’ for I have yet much to say on the behalf of that King Olaf, who, we shall find, is the patron protector of yonder Church at the South-East corner of London Bridge, since he died a Saint and a Martyr. Snorro Sturleson then, having cleared the way for the forcing of London Bridge on the behalf of King Ethelred, thus begins his account of the action, entitling it, in the Scandinavian tongue, Orrosta, or the fight. ‘King Olaf, having determined on the construction of an immense scaffold, to be formed of wooden poles and osier twigs, set about pulling down the old houses in the neighbourhood for the use of the materials. With these Vinea, therefore,’—as such defences were anciently termed—‘he so enveloped his ships, that the scaffolds extended beyond their sides;[23] and they were so well supported, as to afford not only a sufficient space for engaging sword in hand, but also a base firm enough for the play of his engines, in case they should be pressed upon from above. The Fleet, as well as the forces, being now ready, they rowed towards the Bridge, the tide being adverse; but no sooner had they reached it, than they were violently assailed from above with a shower of missiles and stones, of such immensity that their helmets and shields were shattered, and the ships themselves very seriously injured. Many of them, therefore, retired. But Olaf the King and his Norsemen having rowed their ships close up to the Bridge, made them fast to the piles with ropes and cables, with which they strained them, and the tide seconding their united efforts, the piles gradually gave way, and were withdrawn from under the Bridge. At this time, there was an immense pressure of stones and other weapons, so that the piles being removed, the whole Bridge brake down, and involved in it’s fall the ruin of many. Numbers, however, were left to seek refuge by flight: some into the City, others into Southwark. And now it was determined to attack Southwark: but the Citizens seeing their River Thames occupied by the enemy’s navies, so as to cut off all intercourse that way with their interior provinces, were seized with fear, and having surrendered the City, received Ethelred as King. In remembrance of this expedition thus sang Ottar Suarti.’

“And now, Sir, as this is, without any doubt, the first[24] song which was ever made about London Bridge, I shall give you the Norse Bard’s verses in Macpherson’s Ossianic measure, as that into which they most readily translate themselves; premising that the ensuing are of immeasurably greater authenticity.

‘And thou hast overthrown their Bridges, Oh thou Storm of the Sons of Odin! skilful and foremost in the Battle! For thee was it happily reserved to possess the land of London’s winding City. Many were the shields which were grasped sword in hand to the mighty increase of the conflict; but by thee were the iron-banded coats of mail broken and destroyed.’

And ‘besides this,’ continues Snorro, ‘he also sang:’

‘Thou, thou hast come, Defender of the Earth, and hast restored into his Kingdom the exiled Ethelred. By thine aid is he advantaged, and made strong by thy valour and prowess: Bitterest was that Battle in which thou didst engage. Now, in the presence of thy kindred the adjacent lands are at rest, where Edmund, the relation of the country and the people, formerly governed.’

‘Besides this, these things are thus remembered by Sigvatus.’

‘That was truly the sixth fight which the mighty King fought with the men of England: wherein King Olaf,—the Chief himself a Son of Odin, valiantly attacked the Bridge at London. Bravely did the swords of the Völscs defend it, but through the trench which the Sea-Kings, the men of Vikes-land, guarded, they were enabled to come, and the plain of Southwark was full of his tents.’

“Such were the martial feats of King Olafus, upon the water; and now let us turn to his more pious and peaceful actions upon the land, that caused the men of Southwark to found to his honour yonder fane, which still bears his name and consecrates his memory. And in so doing, I pray you to observe that I am not wandering from the subject before us; for that Church is one of the Southern boundaries of London Bridge, and, as such, possesses some interest in its history. The other, on the same side, is the Monastery of St. Mary Overies, of the which I shall hereafter discourse; whilst the two Northern ones are St. Magnus’ Church, and that abode of festivity which rises above us, Fishmongers’ Hall, of which the story will be best noticed when we shall have arrived at the time of the Great Fire. There are within the City walls and Diocese of London, three Churches dedicated to the Norwegian King and Martyr, St. Olaf; and in consequence, Richard Newcourt, in his ‘Repertorium Ecclesiasticum Parochiale Londinense,’ which I shall hereafter notice, volume i. page 509, takes occasion to speak somewhat of his history; collected, most probably, from Adam of Bremen’s ‘Historia Ecclesiarum Hamburgensis et Bremensis.’ He was the Son of Herald Grenscius, Prince of Westfold, in Norway, and was celebrated for having expelled the Swedes from that country, and recovering Gothland. It was after[26] these exploits that he came to England, and remained here as an ally of King Ethelred for three years, expelling the Danes from the Cities, Towns, and Fortresses, and ultimately returning home with great spoil. He was recalled to England by Emma of Normandy, the surviving Queen of his friend, to assist her against Knute; but as he found a paction concluded between that King and the English, he soon withdrew, and was then created King of Norway by the voice of the nation. To strengthen his throne, he married the daughter of the King of Swedeland; but now his strict adherence to the Christian faith, and his active zeal for the spread of it, caused him to be molested by domestic wars, as well as by the Danes abroad: though these he regarded not, since he piously and valiantly professed, that he had rather lose his life and Kingdom than his faith in Christ. Upon this, the men of Norway complained to Knute, King of Denmark, and afterwards of England, charging Olaf with altering their laws and customs, and entreating his assistance; but the Norwegian hero was supported by a young soldier named Amandus, King of Swethland, who had been bred up under Olaf, and taught to fight by him. He, at first, overthrew the Dane in an engagement; but Knute, having bribed the adverse fleet, procured three hundred of his ships to revolt, and then attacking Olaf, forced him to retreat into his own country, where his subjects received him as an enemy. He fled from the disloyal Pagans to Jerislaus, King of Russia, who was his brother-in-law, and remained[27] with him till the better part of his subjects, in the commotions of the Kingdom, calling him to resume his crown, he went at the head of an army; when, whilst one party hailed his return with joy, the other, urged by Knute, opposed him by force, and in a disloyal battle at Stichstadt, to the North of Drontheim, says Newcourt, page 510, with considerable pathos, they ‘murthered this holy friend of Christ, this most innocent King, in Anno 1028,’ but he should have said 1030. His feast is commemorated on the fourth of the Kalends of August, that is to say on the 29th of July; for Grimkele, Bishop of Drontheim, his capital City, a pious priest whom he had brought from England to assist him in establishing Christianity in Norway, commanded that he should be honoured as a Saint, with the title of Martyr. His body was buried in Drontheim, and was not only found undecayed in 1098, but even in 1541, when the Lutherans plundered his shrine of its gold and jewels; for it was esteemed the greatest treasure in the North. Such was St. Olave, to whose memory no less than four Churches in London are dedicated; for, says Newcourt, he ‘had well deserved, and was well beloved of our English Nation, as well for his friendship for assisting them against the Danes, as for his holy and Christian life, by the erection of many Churches which to his honourable memory they built and dedicated to him.’ I notice only one of these, because it is contiguous to London Bridge, which is called St. Olave, Southwark. It stands, as you very well know, on[28] the Northern side of Tooley Street; and although many people would think St. Tooley to be somewhat of a questionable patron for a Church, yet I would remind you that it was only the more usual ancient English name of King Olave, as we are told on good authority, by the Rev. Alban Butler in his ‘Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and other principal Saints,’ London, 1812, 8vo. volume vii. where also, on pages 378-380, you have many further particulars of the life of this heroic Prince. You may also meet with him under a variety of other names, as Anlaf, Unlaf, Olaf Haraldson, Olaus, and Olaf Helge, or Olave the Holy. Of his Church in Southwark I will tell you nothing as to its foundation, but remark only that its antiquity is proved by William Thorn’s ‘Chronicle of the Acts of the Abbots of St. Austin’s Canterbury;’ which is printed in Roger Twysden’s ‘Historiæ Anglicanæ Scriptores Decem;’ London, 1652, folio. Thorn, you may remember, was a Monk of St. Augustine’s, in 1380; and on column 1932 of the volume now referred to, he gives the copy of a grant from John, Earl of Warren, to Nicholas, the Abbot of St. Augustine’s, giving to his Monastery all the estate which it held in ‘Southwark standing upon the River Thames, between the Breggehouse and the Church of Saint Olave.’ By this we know it to be ancient, for that grant was made in the year 1281. And now I will say no more of St. Olave, but that a very full and interesting memoir of him, and his miracles, is to be found in that gigantic work entitled the[29] ‘Acta Sanctorum,’ Antwerp, 1643-1786, 50 volumes, folio, and yet incomplete, for the year descends to October only:—see the seventh volume of July, pages 87-120.

“And now let me chaunt you his Requiem, by giving you, from the same authority, a free translation of the concluding stanza of that Latin Hymn to his memory, which Johannes Bosch tells us was inserted in the Swedish Missal, and sung on his festival; it is in the same measure as the original.

Guardian Saint, whom bliss is ’shrining;

To thy spirit’s sons inclining

From a sinful world’s confining

By thy might, Oh set them free!

Carnal bonds are round them ’twining,

Fiendish arts are undermining,

All with deadly plagues are pining,

But thy power and prayers combining,

Safely shall we rise to thee!—Amen.’

“One of the last notices of London Bridge which occurs in the days of King Ethelred, and I place it here because it is without date, is in his Laws, as they are given in the ‘Chronicon’ of John Brompton, Abbot of Jorvaulx, in the City of York, who lived about the year 1328. His work was printed in Twysden’s Scriptores, which I last quoted; and at column 897, in the xxiii. Chapter of the Statutes there given, is the following passage.

“‘Concerning the Tolls given at Bylyngesgate.

‘If a small ship come up to Bilynggesgate, it shall give one halfpenny of toll: if a greater one which hath sails, one penny: if a small ship, or the hulk of a ship come thereto, and shall lie there, it shall give four pence for the toll. For ships which are filled with wood, one log of wood shall be given as toll. In a week of bread’—perhaps a festival time, ‘toll shall be paid for three days; the Lord’s day, Tuesday, and Thursday. Whoever shall come to the Bridge, in a boat in which there are fish, he himself being a dealer, shall pay one halfpenny for toll; and if it be a larger vessel, one penny.’

“Concerning Brompton’s translation of these laws, Bishop Nicolson, in his ‘English, Scotch, and Irish Historical Libraries,’ London, 1736, folio, page 65, says that they are pretty honestly done, and given at large: but they may be seen with several variations and additions very fairly written in the collections of Sir Simonds D’Ewes, preserved with the Harleian Manuscripts in the British Museum, No. 596. John Brompton, however, at column 891 of his Chronicle, tells us one circumstance more concerning London Bridge before the Invasion of Knute; for he says, under the year 1013, ‘After this, many people were overthrown in the Thames, at London, not caring to go by the Bridge;’ that is to say, because it had been broken in the two recent battles as I have already told you, and there were also erected several fortifications about the City.’

“Perhaps it was the error of Sweyn in getting his Fleet foul of London Bridge, which made Knute the Dane, his Son, go so laboriously to work with the Thames, upon his Invasion in 1016; and I shall give you this very wonderful story in the words of the Saxon Chronicle, page 197. ‘Then came the ships to Greenwich, and, within a short interval, to London; where they sank a deep ditch on the South side, and dragged their ships to the West side of the Bridge. Afterwards they trenched the City without, so that no man could go in or out, and often fought against it; but the Citizens bravely withstood them.’ There are some who doubt this story, but honest William Maitland, who loved to get to the bottom of every thing, as he went sounding about the river for Cæsar’s Ford, also set himself to discover proofs of Knute’s Trench: and you may remember that he tells us, in his work which I have already cited, volume i. page 35, that this artificial water-course began at the great wet-dock below Rotherhithe, and passing through the Kent Road, continued in a crescent form to Vauxhall, and fell again into the Thames at the lower end of Chelsea Reach. The proofs of this hypothesis were great quantities of fascines of hazels, willows, and brushwood, pointing northward, and fastened down by rows of stakes, which were found at the digging of Rotherhithe Dock in 1694; as well as numbers of large oaken planks and piles, also found in other parts.

“Florence of Worcester, who, you will recollect, wrote in 1101, and died in 1119, in his[32] ‘Chronicon ex Chronicis,’ best edition, London, 1592, small 4to. page 413; and the famous old Saxon Chronicle, page 237; also both mention the easy passage of the rapacious Earl Godwin, as he passed Southwark in the year 1052. The tale is much the same in each, but perhaps the latter is the best authority, and it runs thus. ‘And Godwin stationed himself continually before London, with his Fleet, until he came to Southwark; where he abode some time, until the flood came up. When he had arranged his whole expedition, then came the flood, and they soon weighed anchor and steered through the Bridge by the South side.’ This relation is also supported by Roger Hoveden, in his Annals, Part I. in ‘Rerum Anglicarum Scriptores post Bedam,’ by Sir H. Savile, folio 253b, line 41.

“And now, worthy Mr. Barbican, before we enter upon the conjectures and disputes relating to the real age and founders of the first Wooden Bridge over the Thames at London, let me give you a toast, closely connected with it, in this last living relique of old Sir John Falstaff. You must know, my good Sir, that when the Church-Wardens and vestry of St. Mary Overies, on the Bankside yonder, meet for conviviality, one of their earliest potations is to the memory of their Church’s Saint and the patroness who feeds them, under the familiar name of ‘Old Moll!’ and therefore, as we are now about to speak of them and their pious foundation most particularly, you will, I doubt not, pledge me heartily to the Immortal Memory of Old Moll!”

“I very much question,” returned I, “if either the good foundress of the Church, or she to whom it was dedicated,—if Mary the Saint, or Mary the Sinner,—were ever addressed by so unceremonious an epithet in their lives; but, however, as it’s a parochial custom, and your wish, here’s Prosperity to St. Saviour’s Church, and the Immortal Memory of Old Moll!” Mr. Postern having made a low bow of acknowledgment for my compliance, thus continued.

“I have made it evident then, and, indeed, it is agreed to on all sides, that there was a Wooden Bridge over the Thames, at London, at least as early as the year 1052; and Maitland, at page 44 of his History, is inclined to believe that it was erected between the years 993 and 1016, at the public cost, to prevent the Danish incursions up the River. John Stow, however, in volume i., page 57, of his ‘Survey,’ attributes the building of the first Wooden Bridge over the Thames, at London, to the pious Brothers of St. Mary’s Monastery, on the Bankside. He gives you this account on the authority of Master Bartholomew Fowle, alias Fowler, alias Linsted, the last Prior of St. Mary Overies; who, surrendering his Convent on the 14th of October, 1540,—in the 30th year of Henry VIII.,—had a pension assigned him of £100 per Annum, which it is well known, that he enjoyed until 1553. This honest gentleman you find spoken of in John Stevens’s ‘Supplement to Sir William Dugdale’s Monasticon Anglicanum,’ London, 1723, folio, volume ii., page 98; and from him old Stow states, that,[34] ‘a Ferry being kept in the place where now the Bridge is built, the Ferryman and his wife deceasing, left the said Ferry to their only daughter, a maiden named Mary; which, with the goods left her by her parents, as also with the profits rising of the said Ferry, built a house of Sisters in the place where now standeth the East part of St. Mary Overies Church, above the choir, where she was buried. Unto the which house she gave the oversight and profits of the Ferry. But afterwards, the said house of Sisters being converted into a College of Priests, the Priests built the Bridge of Timber, as all the other great Bridges of this land were, and, from time to time, kept the same in good reparations. Till at length, considering the great charges of repairing the same, there was, by aid of the Citizens of London, and others, a Bridge built with arches of stone, as shall be shewed.’

“The first who attacks this story is William Lambarde, the Perambulator of Kent, in his ‘Dictionarium Angliæ Topographicum et Historicum,’ London, 1730, quarto, page 176; wherein he scruples not to call Prior Fowler ‘an obscure man,’ whom he charges with telling this narrative, ‘without date of time, or warrant of writing,’ and then sums up his remarks in these words. ‘As for the first buildinge, I leave it to eche man’s libertye what to beleve of it; but as for the name Auderie, I think Mr. Fowler mistoke it, for I finde bothe in the Recordes of the Queene’s Courtes and otherwise, it signifieth over the water, as Southrey, on the South side of the water: the ignorance whereof,[35] might easily dryve Fowler—a man belyke unlearned in the Saxon tongue,—to some other invention.’

“Maitland and Entick, at page 44 of their History, are not much more believing than Lambarde, the Lawyer; for they assert that the Convent of Bermondsey, founded by Alwin Child, a Citizen of London, in the year 1082, was the first religious house on the South side of the River, within the Bills of Mortality. The second, say they, speaking after Sir William Dugdale in his ‘Monasticon Anglicanum,’ London, 1661, folio, pages 84, 940, was the Priory of St. Mary Overies, founded by William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester, in the reign of King Henry I. Now Bishop Tanner, in his ‘Notitia Monastica,’ best edition by James Nasmith, Cambridge, 1787, folio, XX. Surrey,—for you know the book is unpaged and arranged alphabetically under Counties, of which Pennant heavily complains,—is inclined to think that Stow was in the right, although he had not discovered any thing either in print or manuscript to support his narrative. He is also willing to believe, that Bishop Giffard did not do more for St. Mary Overies, than rebuild the body of the Church: and, certainly, that he did not, in 1106, place Regular Canons there, since he refers to Matthew of Westminster to prove that they were then but newly come into England, and placed in that Church; whilst Bishop Giffard was himself in exile until the year 1107. The ‘Domesday Book,’ also, the most veritable and invaluable record of our land, thus hints at a Religious House in Southwark;[36] which, as that Survey was made about the year 1083, was, of course, long anterior to the times of which I spake last. You will find the passage in Nichols’ edition of the register, London, 1783, folio, volume i. Sudrie, folio 32 a, column 1; and the words are as follow. ‘The same Bishop,’—that is to say, Odo, Bishop of Baieux,—‘has in Southwark one Monastery, and one Harbour. King Edward held it on the day he died.’—January the 5th, 1066—‘Whoever had the Church, held it of the King. From the profits of the Harbour, where ships were moored, the King had two parts.’ ‘Now,’ concludes the worthy Dr. Tanner, ‘if Monasterium here denote any thing more than an ordinary Church, it may be thought to mean this Religious House, there being no pretence for any other in this Borough to claim to be as old as the Confessor’s time, or, indeed, as the making of the Domesday Book, A. D. 1083.’ Vide Sign. U u 2; Notes r, and s.

“Maitland, however, cannot be brought to believe in the foundation of a Wooden Bridge by the Brethren of St. Mary; and on page 44 of his work, already cited, he thus gives the reasons for his non-conformity. ‘As the Ferry,’ he commences, ‘is said to have been the chief support of the Priory,[37] ’twould have been ridiculous in the Prior and Canons, to have sacrificed their principal dependence, to enrich themselves by a wild chimera of increasing their revenues in the execution of a project, which, probably, would have cost six times the sum of the intrinsic value of their whole estate; and, when effected, would, in all likelihood, not have brought in so great an annual sum as the profits arising by the Ferry, seeing it may be presumed that foot-passengers would have been exempt from Pontage.’ He next proceeds to quote a deed of King Henry I., which I shall produce in its proper order of time, exempting certain Abbey lands from being charged with the work of London Bridge: which he considers as a sufficient proof that the Priests of St. Mary did not preserve the erection in repair, and therefore, says he, ‘as the latter part of this traditionary account is a manifest falsehood, the former is very likely to be of the same stamp.’ He then sums up all by these bold words. ‘As it appears that some religious foundations only were exempt from the work of this Bridge, and they, too, by charter, I think ’tis not to be doubted, but all civil bodies and incorporations were liable to contribute to the repairs thereof. And, consequently, that Linsted and his followers exceed the truth, by ascribing all the praise of so public a benefaction to a small House of Religious; who, with greater probability, only consented to the building of this Bridge, upon sufficient considerations and allowances, to be made to them for the loss of their Ferry, by which they had been always supported.’ Such are the objections against the attributing the building of the First Wooden Bridge to the Monks of Southwark; but we may remark, by the way, that Stow was a laborious and inquisitive Antiquary, who saw and inquired, as well as read for himself, and, in all probability, had both seen and[38] conversed with Prior Fowle; whilst Maitland and Entick were often contented to write in their libraries from the works of others, and speak of places with which they were but very slightly acquainted. We may add too, that, as the Priests of St. Mary were Regular Canons of St. Austin, by their rule they were not permitted to be wealthy, but were to sell the whole of their property, give to the poor, have all things in common, and never be unemployed. I know very well, that in opposition to Stow’s account of Mary Audery’s foundation, you may bring forward that assertion made in Stevens’s ‘Supplement to Dugdale,’ which I have already cited, volume ii. page 97; wherein she is called ‘a noble woman,’ and, consequently, could not be the Ferryman’s daughter. But of this let me observe, that the authority of Stow’s ‘Survey,’ given in the margin, is mis-quoted; for although it is certain that the action itself was sufficiently noble, yet the old Citizen never calls her other than ‘a Maiden named Mary.’ You may see the place to which Stevens refers, in Strype’s edition of the ‘Survey,’ volume ii. page 10; and let me remark now, before I quit the history of St. Mary Overies, as connected with that of London Bridge, that there is yet extant there, a monumental effigy conveying the strongest lesson of man’s mortality; it being the resemblance of a body in that state, when corruption is beginning its great triumph. Prating Vergers and Sextons commonly tell you, that the persons whom these figures represent, endeavoured to fast the whole of Lent, in[39] imitation of the great Christian pattern, and that dying in the act, they were reduced to such a cadaverous appearance at their decease. There has, however, been a new legend invented for this sculpture, as it is commonly reported to be that of Audery, the Ferryman,

father of the foundress of St. Mary Overies. It was formerly placed on the ground, under the North window of the Bishop’s Court, which, before the present repairs, stood at the North East corner of the Chapel of the Virgin Mary. Where it will be removed[40] to hereafter, time only can unfold, for, as yet, even the Churchwardens themselves know not.

“In speaking of this person’s tomb, I must not, however, omit to notice, that there is a singularly curious, although, probably, fabulous tract of 30 pages, of his life, the title of which I shall give you at length. ‘The True History of the Life and sudden Death of old John Overs, the rich Ferry-Man of London, shewing, how he lost his life, by his own covetousness. And of his daughter Mary, who caused the Church of St. Mary Overs in Southwark to be built; and of the building of London Bridge.’ There are two editions of this book, the first of which was published in 12mo., in 1637, and a reprint of it in 8vo., which, though it be shorn of the wood-cuts that decorated the Editio Princeps, is, perhaps, the most interesting to us, inasmuch as it bears this curious imprint.—‘London: Printed for T. Harris at the Looking-Glass, on London Bridge: and sold by C. Corbet at Addison’s Head, in Fleet-street, 1744. Price six pence.’ You may see this work in Sir W. Musgrave’s Biographical Tracts in the British Museum; its first nine pages are occupied with a definition and exhortation against covetousness, in the best Puritanic style of the seventeenth century; and then, on page 10, the history opens thus:—[41]‘Before there was any Bridge at all built over the Thames, there was only a Ferry, to which divers boats belonged, to transport all passengers betwixt Southwark and Churchyard Alley, that being the high-road way betwixt Middlesex, and Sussex, and London. This Ferry was rented of the City, by one John Overs, which he enjoyed for many years together, to his great profit; for it is to be imagined, that no small benefit could arise from the ferrying over footmen, horsemen, all manner of cattle, all market folks that came with provisions to the City, strangers and others.’