The Project Gutenberg EBook of London City, by Walter Besant Title: London City Author: Walter Besant Produced by Richard Tonsing, Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Pictorial Agency.

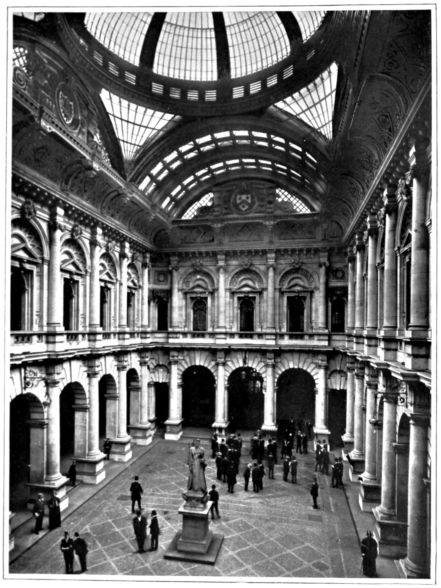

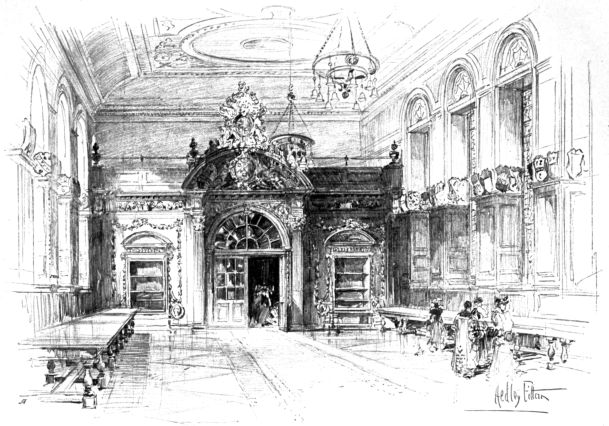

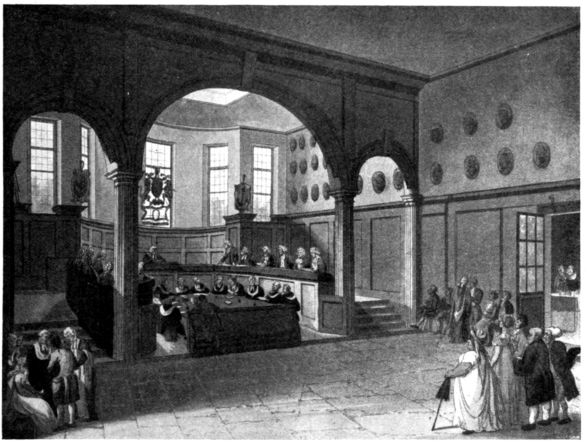

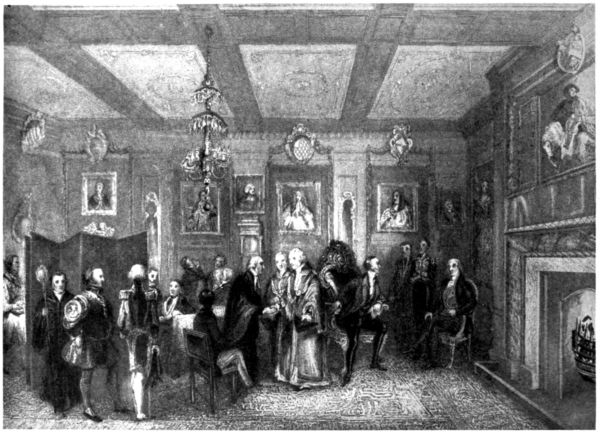

INTERIOR OF ROYAL EXCHANGE.—(Page 128)

LONDON

CITY

PREFACE

With this volume we begin what may be called the second part of the Survey. All that has preceded it has dealt with the history of London as a whole; now we turn to London in its topographical aspect and treat it street by street, with all the historical associations interwoven in a continuous narrative with a running commentary of the aspect of the streets as they were at the end of the nineteenth century, for the book is strictly a Survey of London up to the end of the nineteenth century. Sir Walter Besant himself wrote the greater part of the volume now issued, calling it “The Antiquities of the City,” and it is exclusively confined to the City. For the topographical side of the great work, however, he employed assistants to collect material for him and to help him; for though, as he said, he had been “walking about London for the last thirty years and found something fresh in it every day,” he could not himself collect the mass of detail requisite for a fair presentation of the subject. In the present volume, therefore, embedded in his running commentary, will be found detailed accounts of the City Companies, the City churches and other buildings, which are not by his hand. A word as to the plan on which the volume is made may be helpful. In cases where the City halls are standing, accounts of the Companies they belong to are inserted there in the course of the perambulation; but where the Companies possess no halls, the matter concerning them is relegated to an Appendix. The churches, however, being peculiarly associated with the sites on which they are standing, or stood, are considered to be an integral part of the City associations, and churches, whether vanished or standing, are noted in course of perambulation. A distinction which shows at a glance whether any particular church is still existing or has been demolished is made by the type; for in the case of an existing church the name is viset in large black type, as a centre heading, whereas with a vanished church it is given in smaller black type set in line.

The plan of the book is simplicity itself; it follows the lines of groups of streets, taken as dictated by common sense and not by the somewhat arbitrary boundaries of wards. The outlines of these groups are clearly indicated on the large map which will be found at the end of the volume.

CONTENTS

THE ANTIQUITIES OF THE CITY

| GROUP I | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Streets North and South of Cheapside and the Poultry | 1 |

| GROUP II | |

| Streets North of Gresham Street and West of Moorgate Street | 63 |

| GROUP III | |

| Streets between Moorgate and Bishopsgate Streets | 91 |

| GROUP IV | |

| Streets between Fenchurch and Bishopsgate Streets | 146 |

| GROUP V | |

| Thames Street and the Streets North and South of it | 190 |

| The Tower of London | 288 |

| GROUP VI | |

| Newgate Street and the Streets North and South of it | 300 |

| St. Paul’s | 327 |

| GROUP VII | |

| Fleet Street and the adjacent Courts (including the Temple and the Rolls) | 362 |

| The Temple | 370 |

| The Ancient Schools in the City of London | 385 |

| viiiAPPENDICES | |

| 1. The City Companies | 433 |

| 2. Mayors and Lord Mayors of London from 1189 to 1900 | 455 |

| 3. A Calendar of the Mayors and Sheriffs of London from 1189 to 1900 | 461 |

| INDEX | 483 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

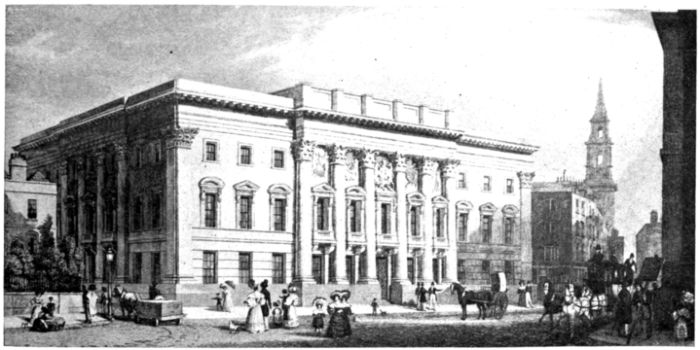

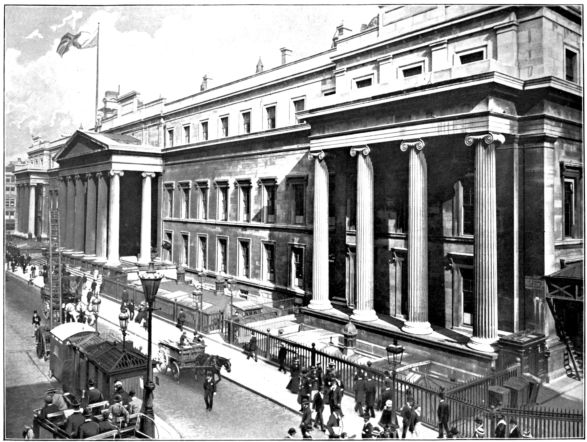

| Interior of Royal Exchange | Frontispiece | |

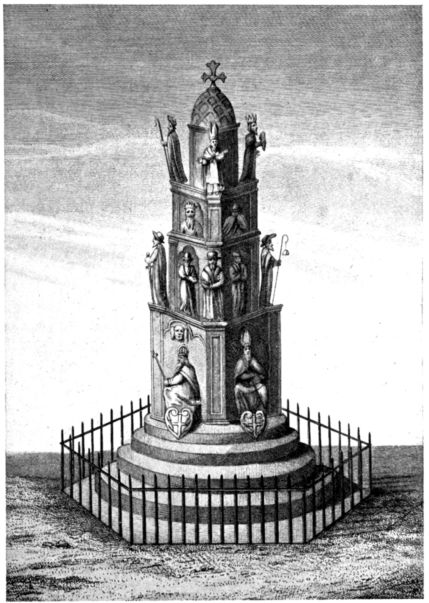

| Cheapside Cross (as it appeared on its erection in 1606) | 5 | |

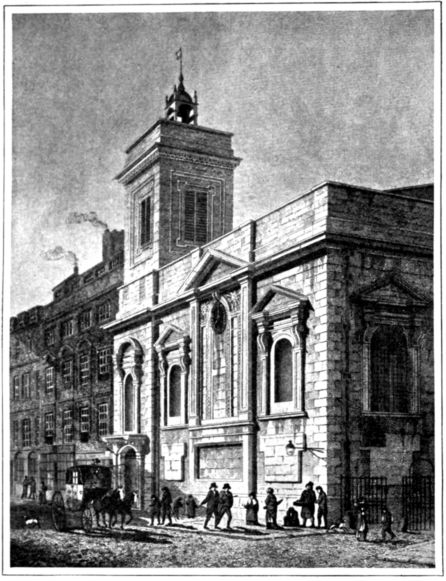

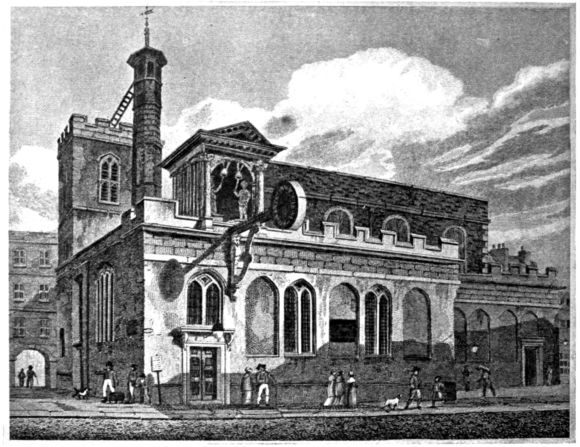

| St. Mildred, Poultry | 18 | |

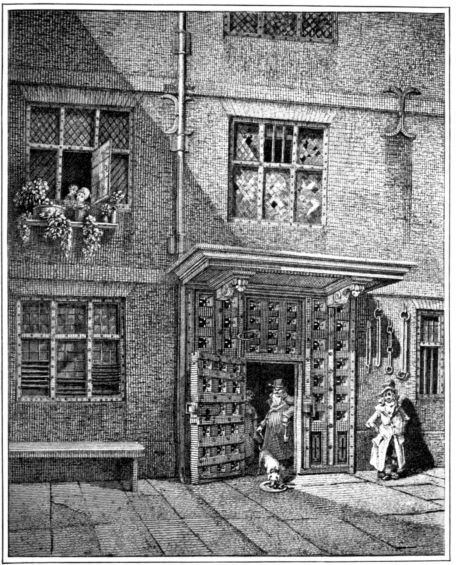

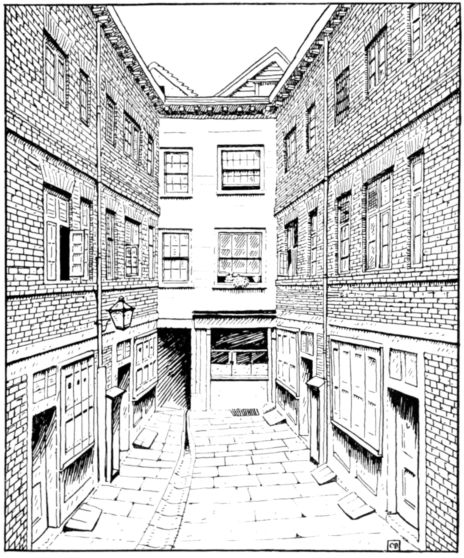

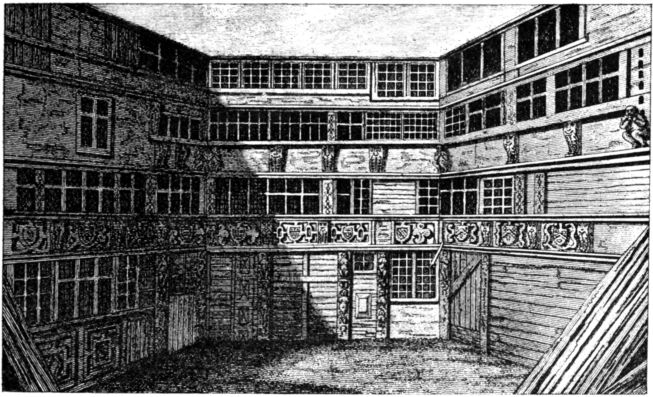

| Inside the Poultry Compter | 19 | |

| St. Lawrence, Jewry | 26 | |

| SS. Anne and Agnes | 27 | |

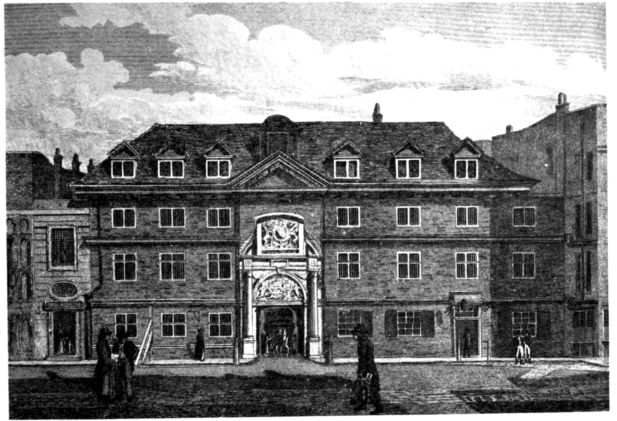

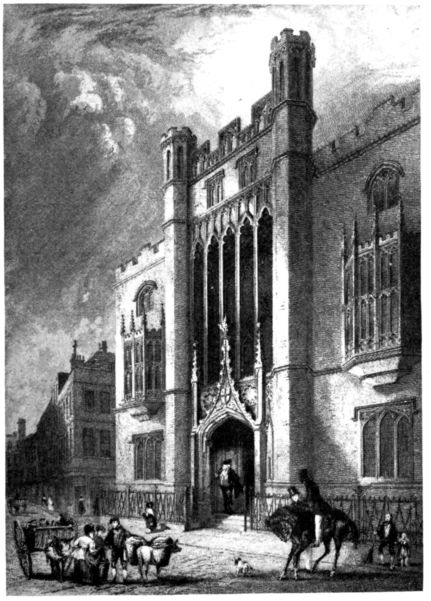

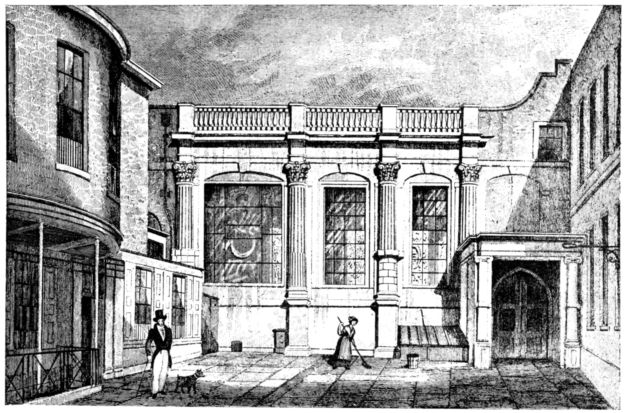

| Blackwell Hall, 1819 | 31 | |

| Mercers’ Hall: Interior | Facing | 32 |

| Mercers’ Hall | 35 | |

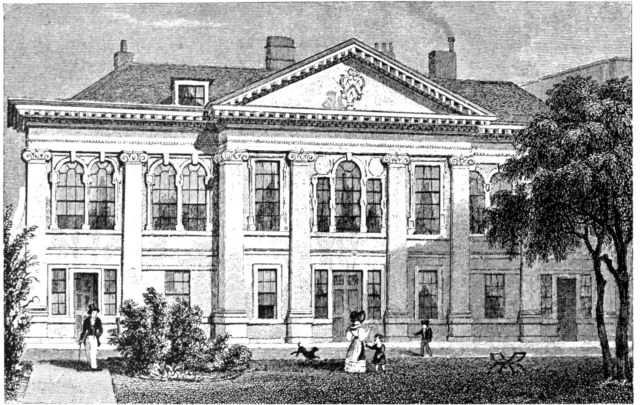

| City of London School, Milk Street | 39 | |

| Church of St. Vedast | 43 | |

| Goldsmiths’ Hall, 1835 | 45 | |

| Gerard’s Hall Crypt in 1795 | 57 | |

| The Armourers’ and Brasiers’ Almshouses, Bishopsgate Without, 1857 | 65 | |

| St. Mary, Aldermanbury, in 1814 | 70 | |

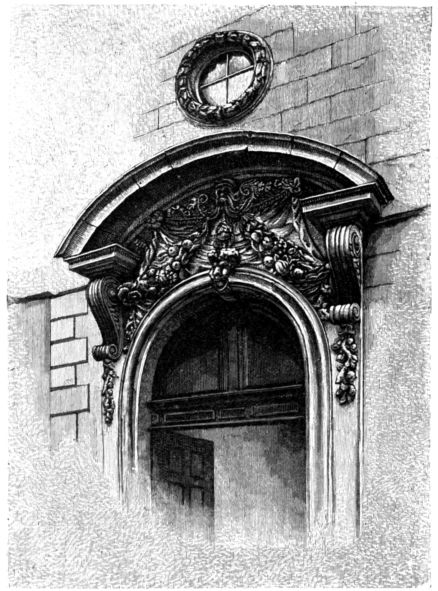

| Porch of St. Alphage, London Wall, 1818 | 72 | |

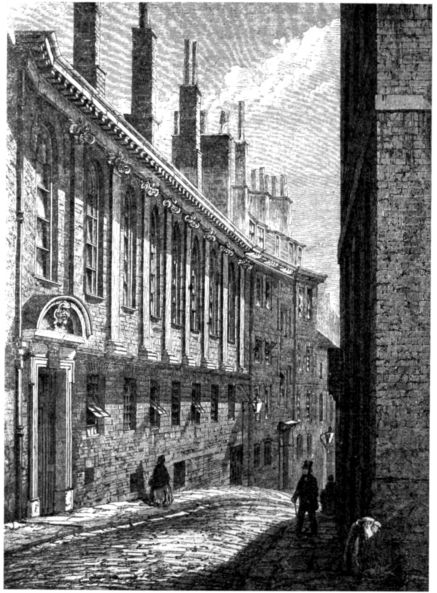

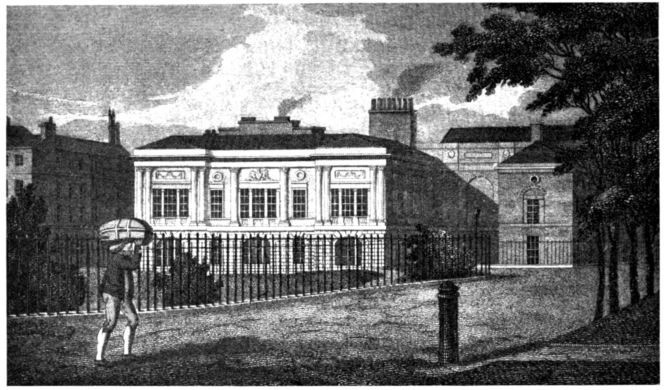

| Sion College, London Wall, 1800 | 73 | |

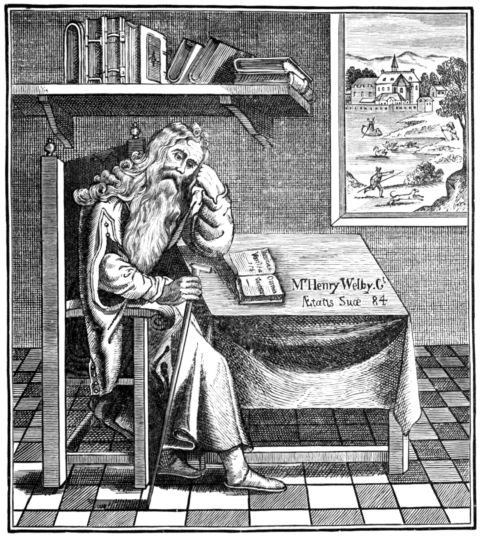

| Grub Street Hermit | 77 | |

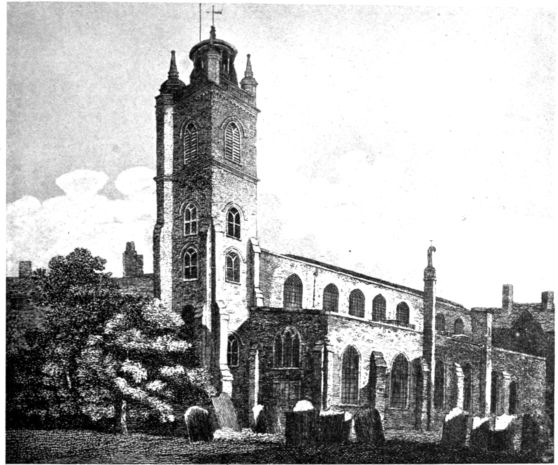

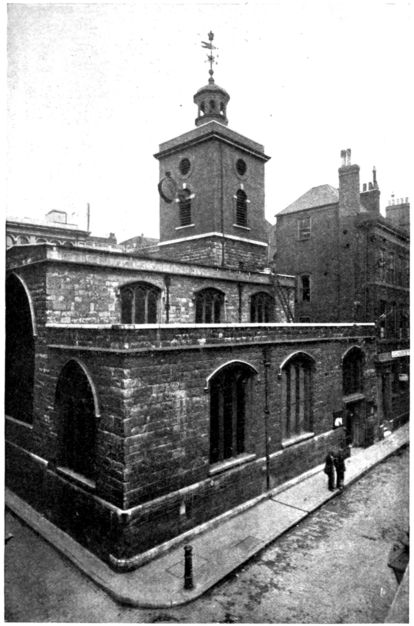

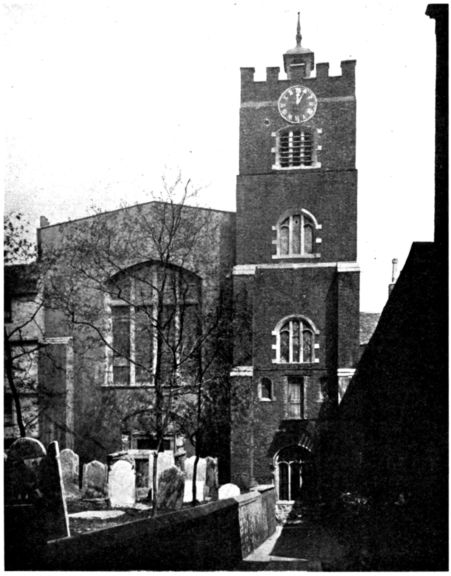

| St. Giles, Cripplegate | 81 | |

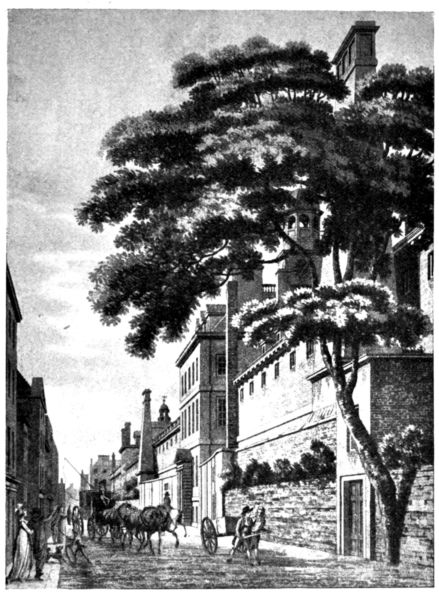

| London Wall | 83 | |

| The Pump in Cornhill, 1800 | 93 | |

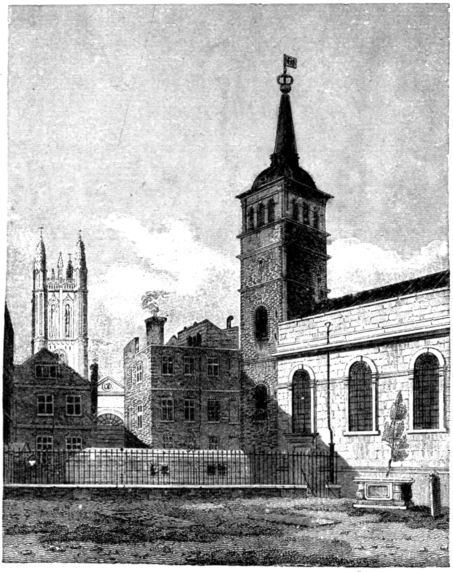

| St. Peter’s, Cornhill | 96 | |

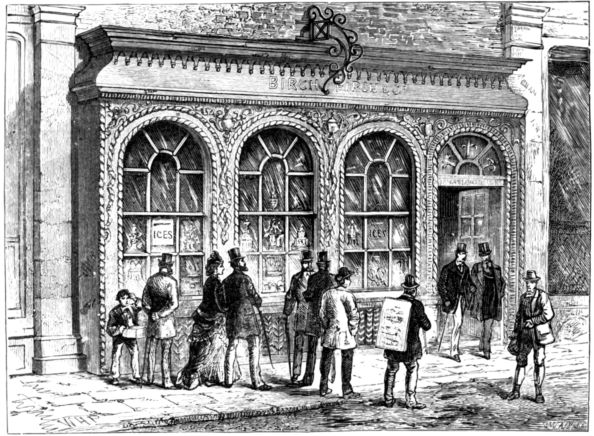

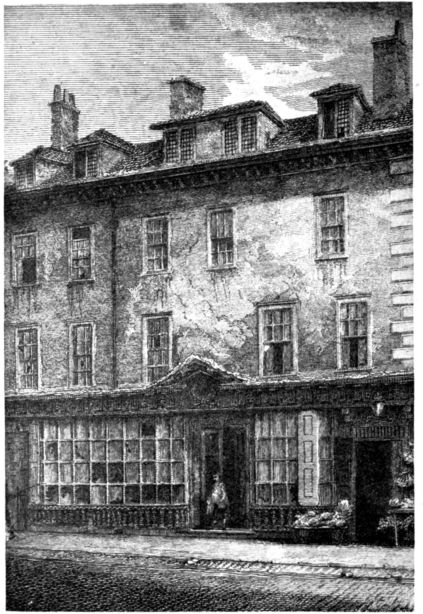

| Confectioner’s Shop, Cornhill | 98 | |

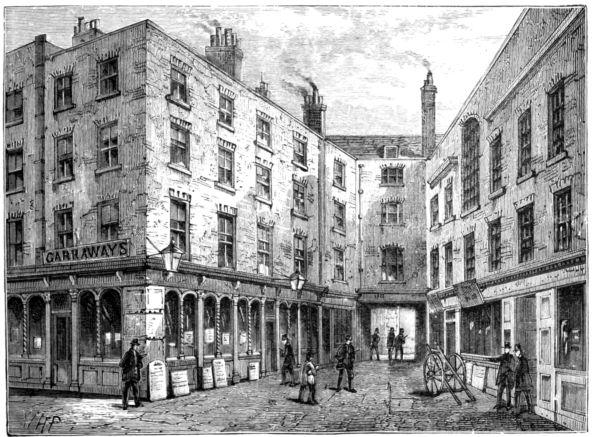

| Garraway’s Coffee-House | 99 | |

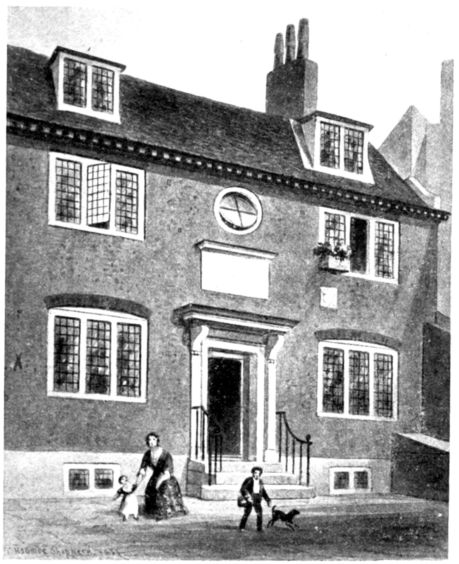

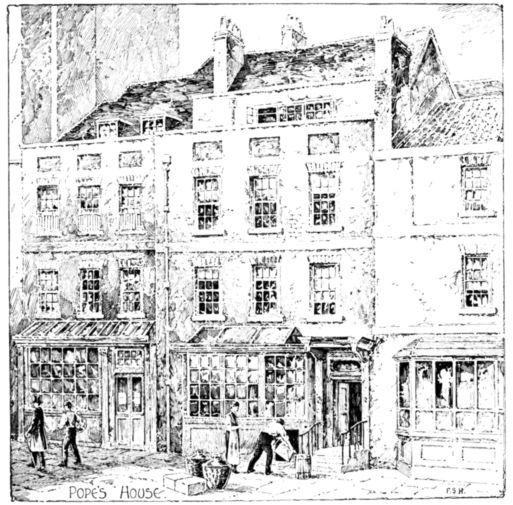

| Pope’s House in Plough Court | 103 | |

| St. Mary Woolnoth | Facing | 106 |

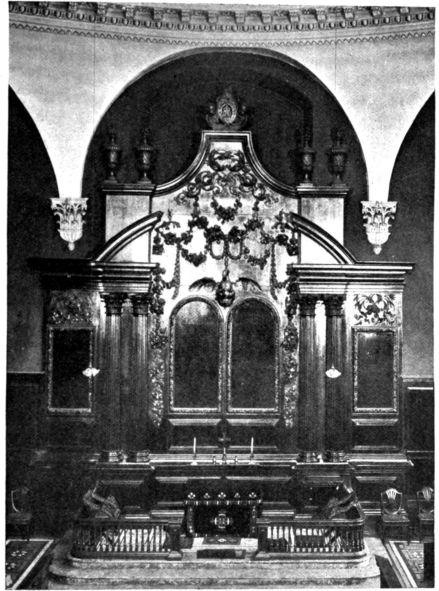

| Altar of St. Mary Abchurch | 109 | |

| Salters’ Hall, 1822 | 113 | |

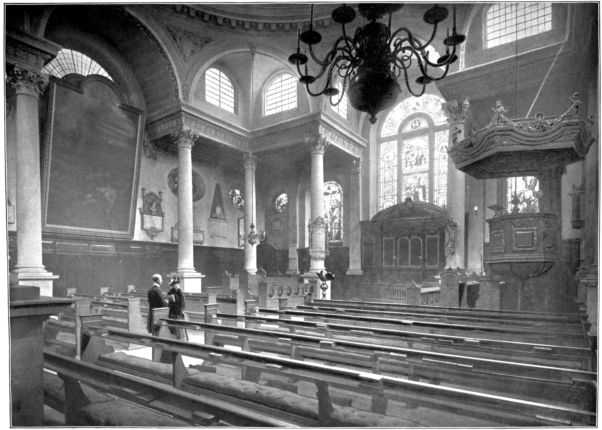

| St. Stephen, Walbrook | Facing | 118 |

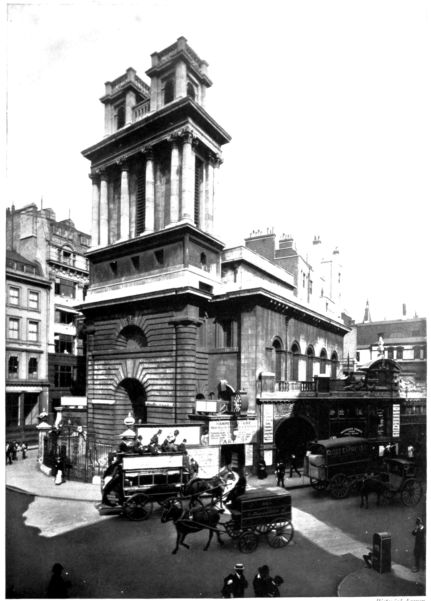

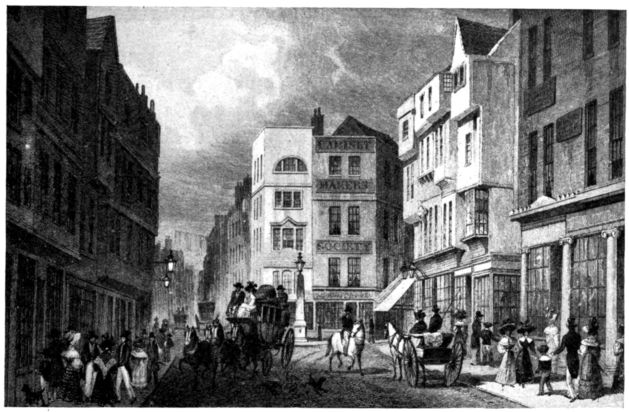

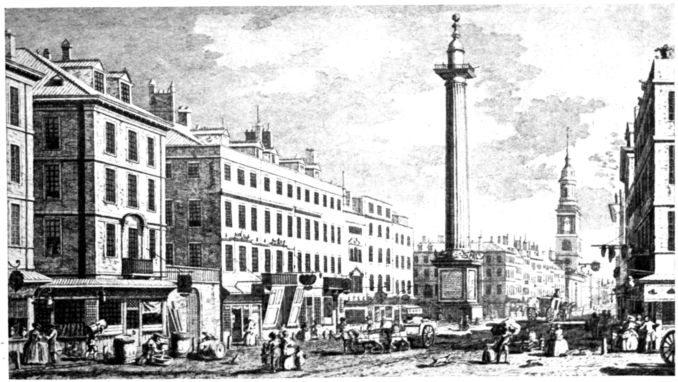

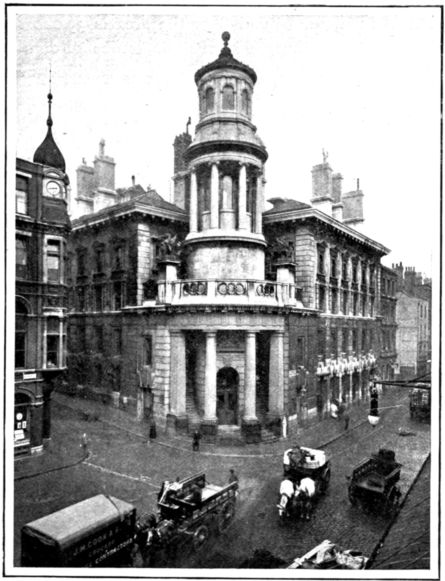

| The Mansion House and Cheapside | 120 | |

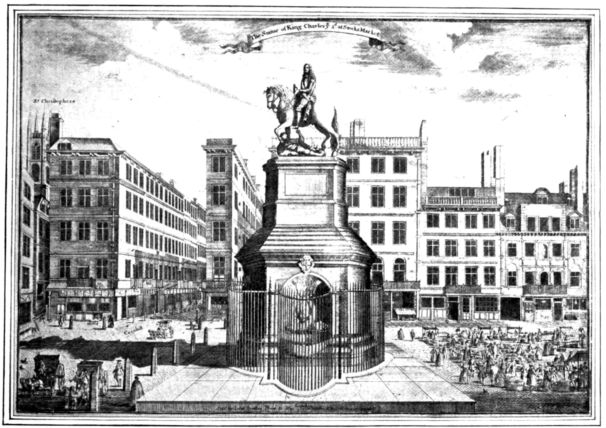

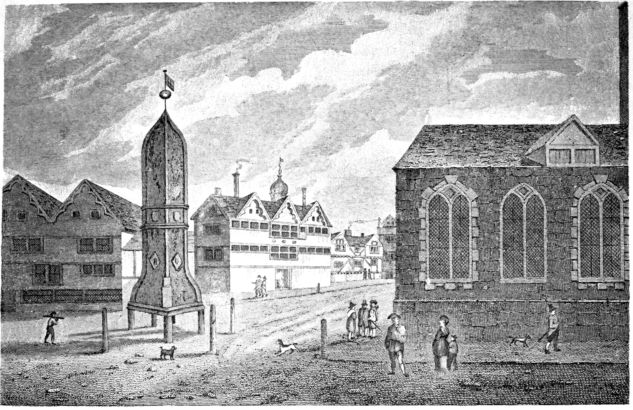

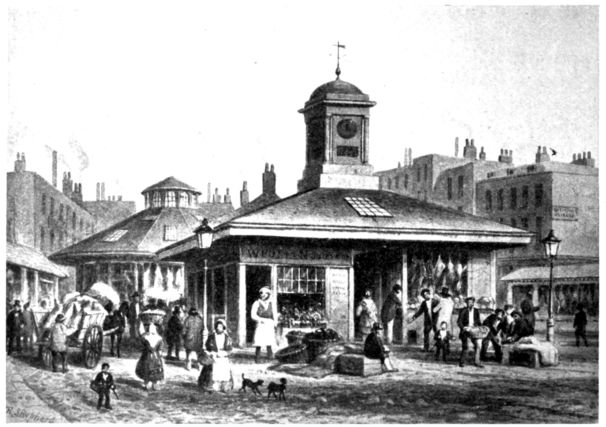

| Stocks Market | 123 | |

| Bank of England Fountain | Facing | 126 |

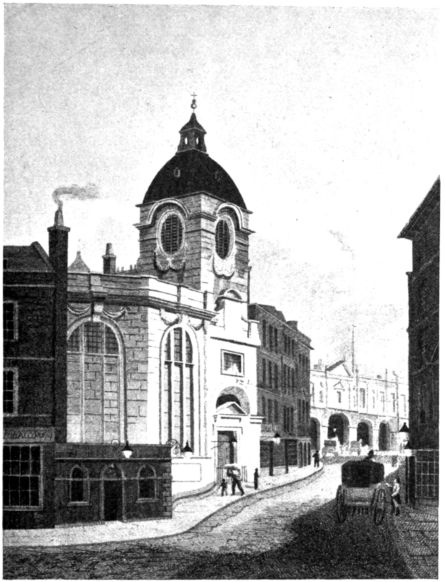

| St. Benet Finck | 129 | |

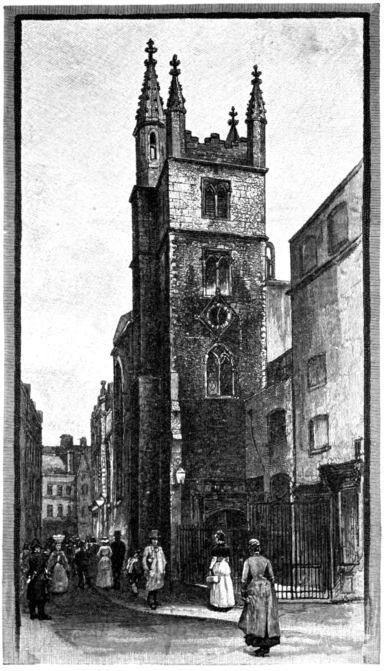

| xSt. Martin Outwich | 131 | |

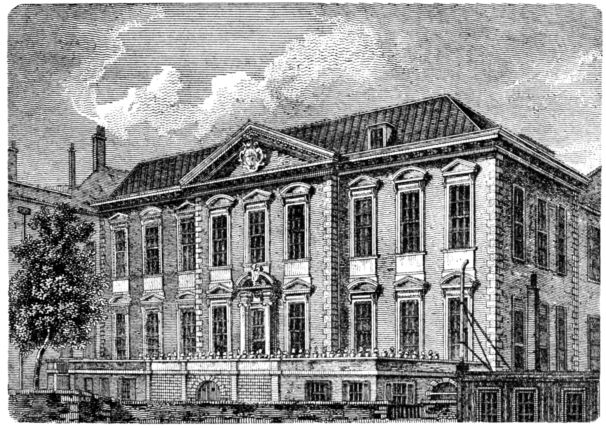

| Gresham College | 135 | |

| Carpenters’ Hall, London Wall, 1830 | 144 | |

| Ironmongers’ Hall in the Eighteenth Century | 149 | |

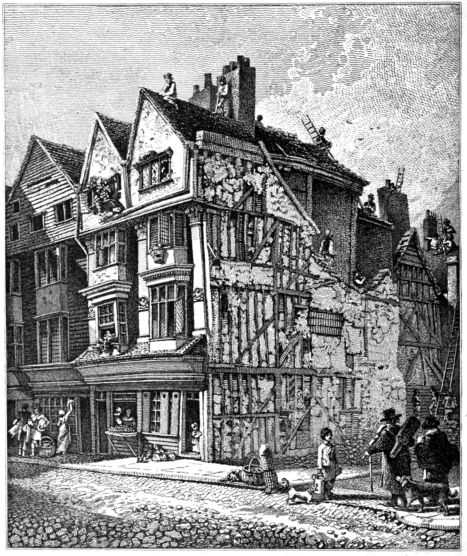

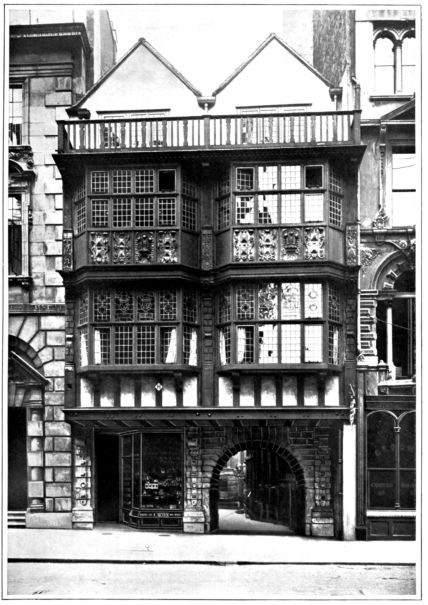

| A Remarkable Old House in Leadenhall Street | 154 | |

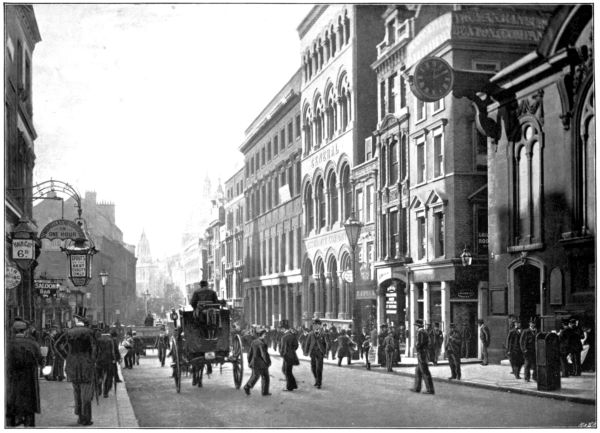

| Leadenhall Street | 155 | |

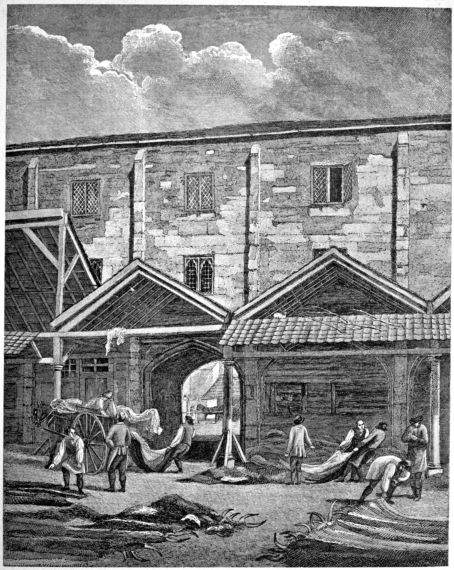

| Skin Market, Leadenhall, 1825 | 157 | |

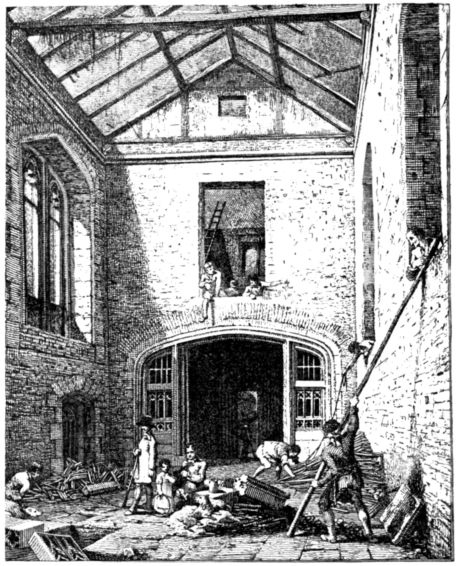

| Leadenhall Chapel in 1812 | 160 | |

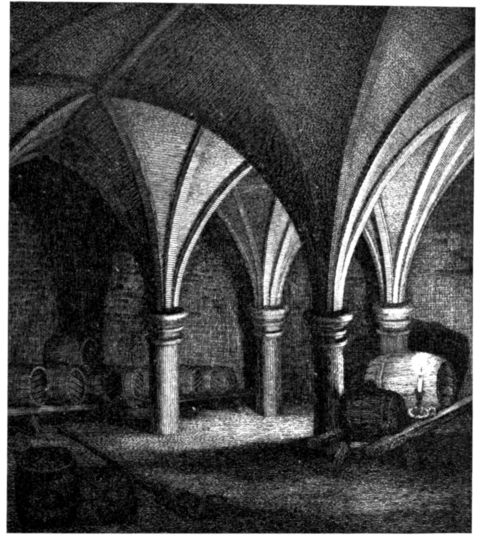

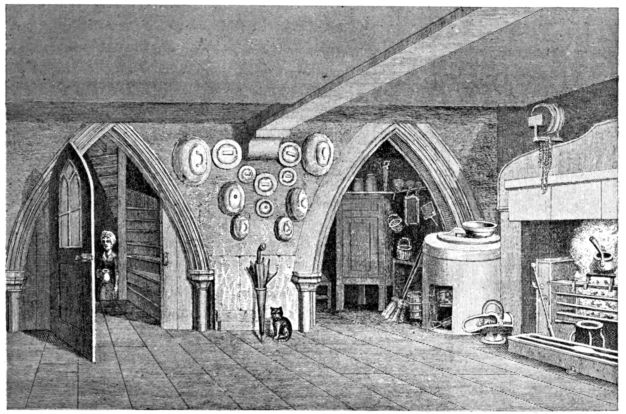

| Crypt in Leadenhall Street, 1825 | 161 | |

| Aldgate in 1830 | 169 | |

| St. Andrew Undershaft | 173 | |

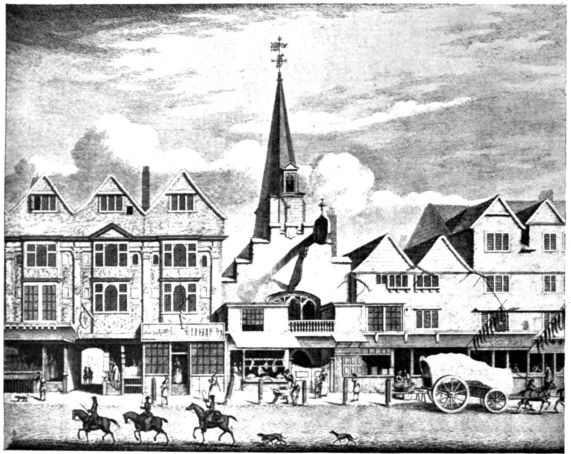

| Bishopsgate Street, showing Church of St. Martin Outwich, and the Pump, 1814 | 177 | |

| St. Helen, Bishopsgate, 1817 | 179 | |

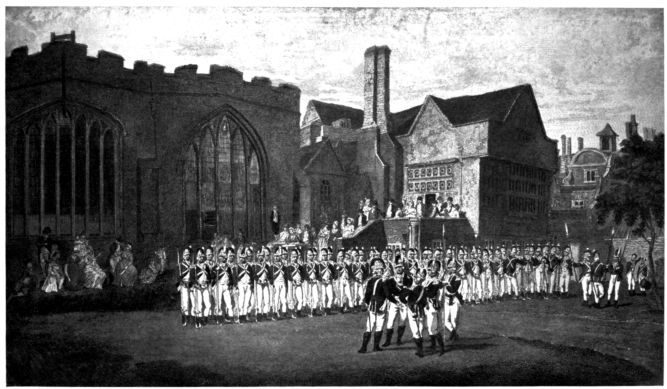

| Cornhill Military Association, with a View of the Church of St. Helen’s, and Leathersellers’ Hall | Facing | 180 |

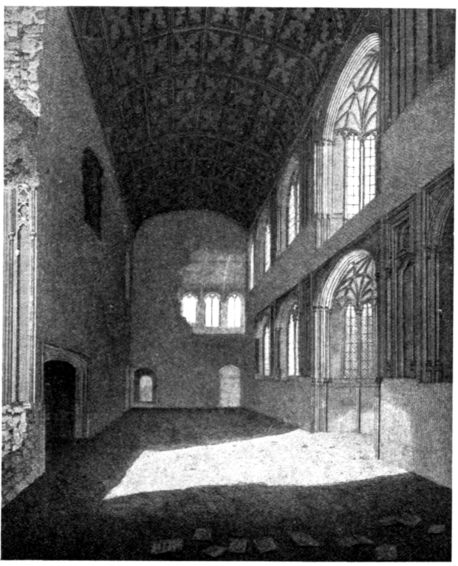

| Council Room, Crosby Hall, 1816 | 181 | |

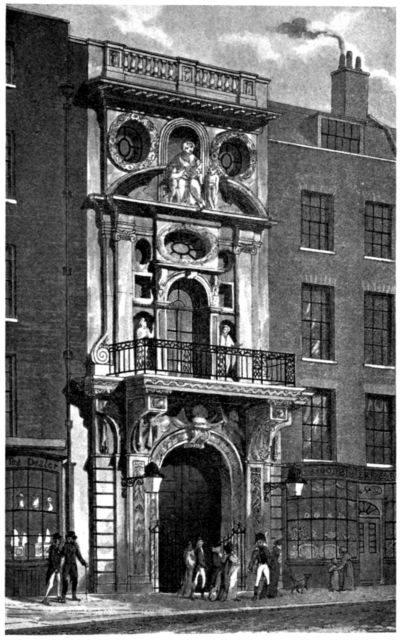

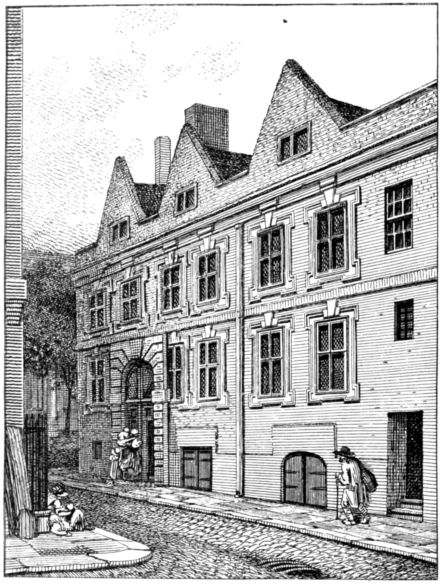

| Principal Entrance to Leathersellers’ Hall. Demolished 1799 | 184 | |

| St. Ethelburga, Bishopsgate Street | 186 | |

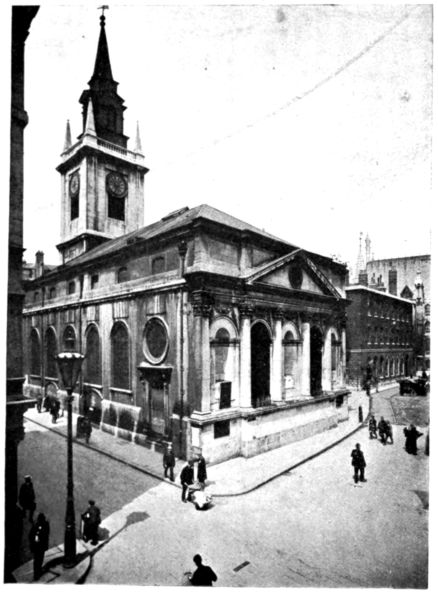

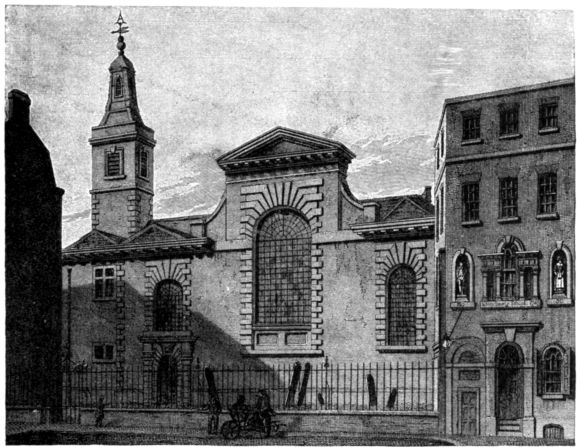

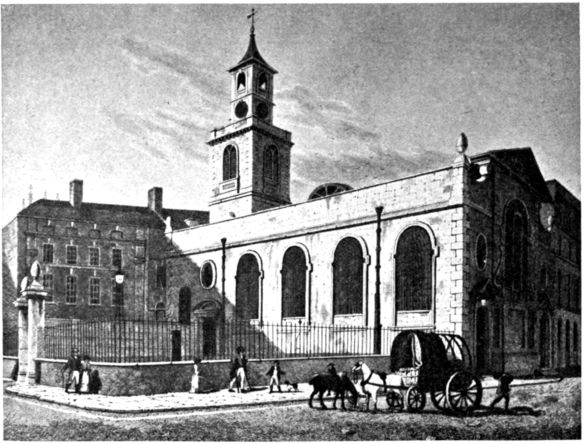

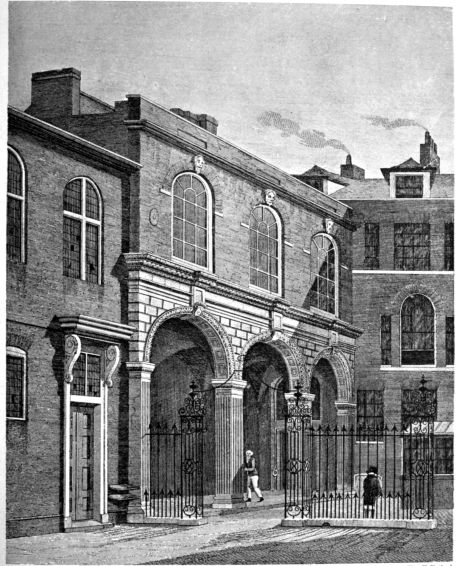

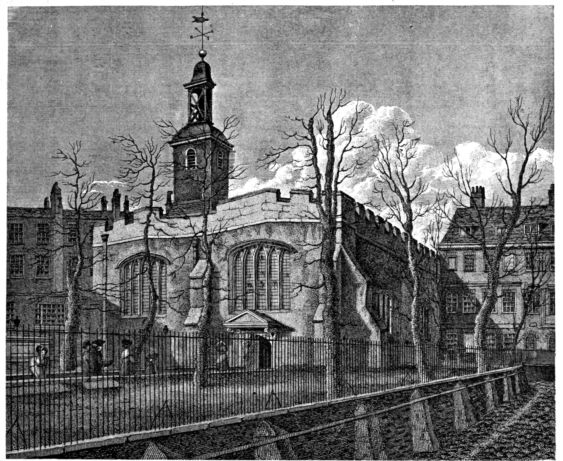

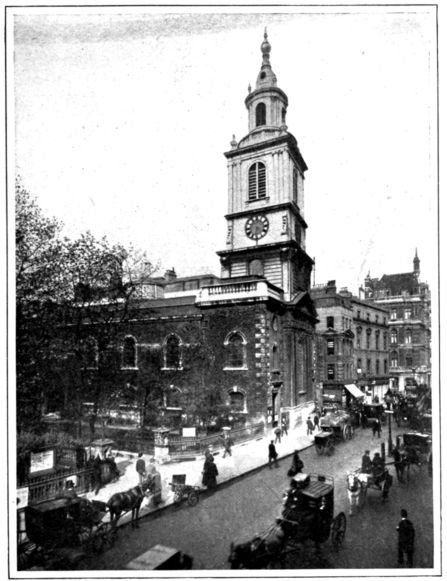

| St. Botolph, Bishopsgate | 187 | |

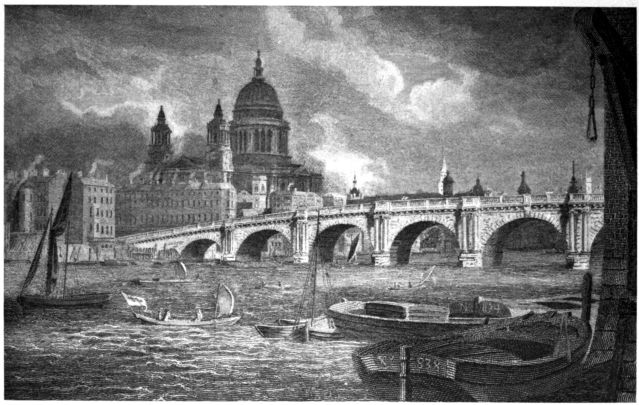

| Blackfriars Bridge, 1796 | 193 | |

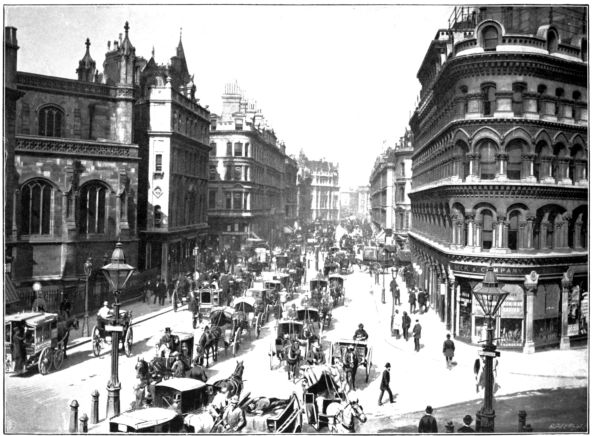

| Ludgate Circus and Ludgate Hill | 198 | |

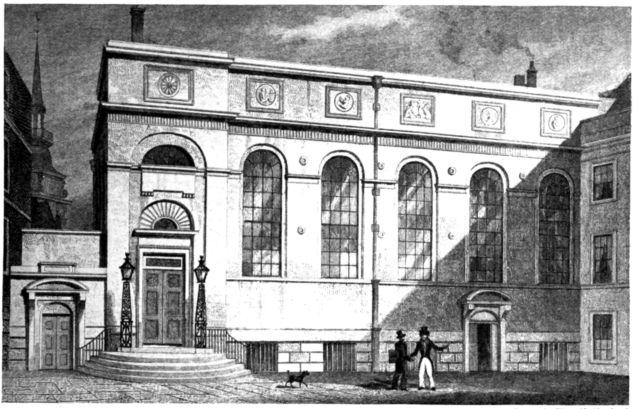

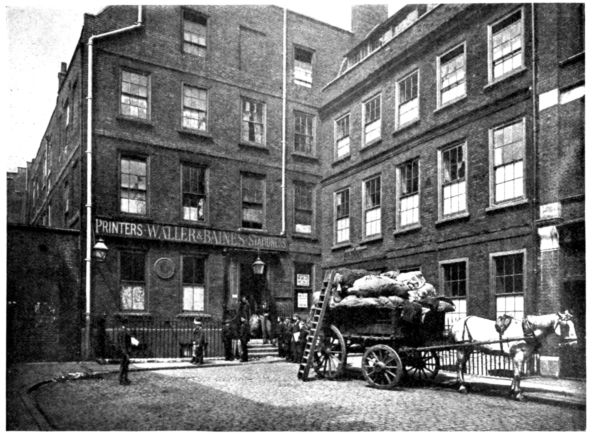

| Stationers’ Hall in 1830 | 199 | |

| Stationers’ Hall (Interior) | 201 | |

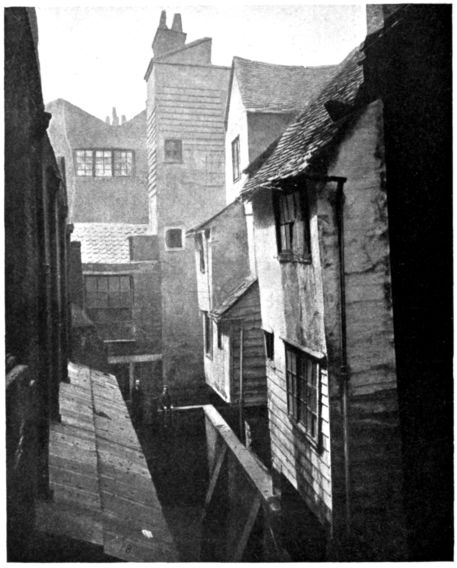

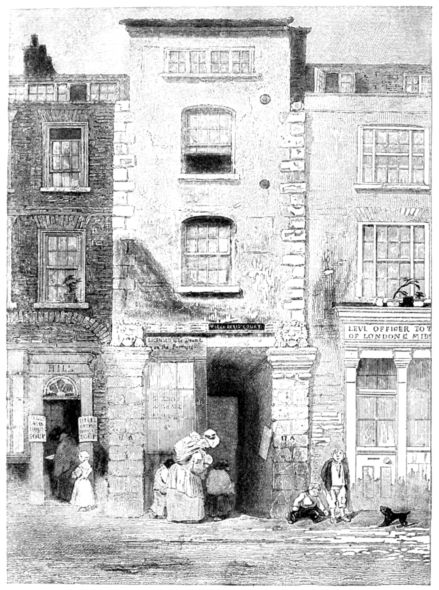

| Fleur-de-lys Court | 203 | |

| British and Foreign Bible Society House | Facing | 206 |

| The College of Arms | 209 | |

| Doctors’ Commons, 1808 | 211 | |

| Queen Victoria Street | Facing | 214 |

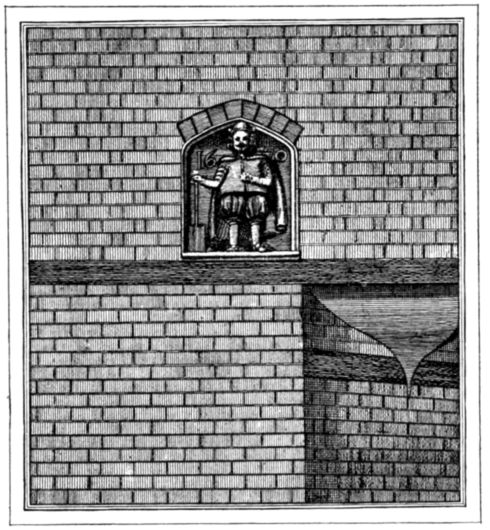

| A Bas-relief of a Gardener, Gardeners’ Lane, 1791 | 219 | |

| Council Chambers, Vintners’ Hall | 230 | |

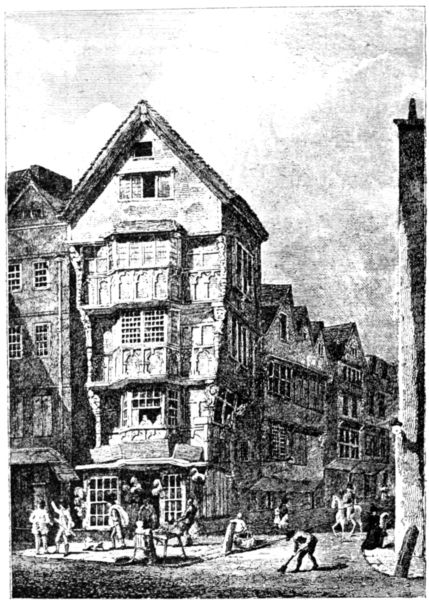

| Whittington’s House | 236 | |

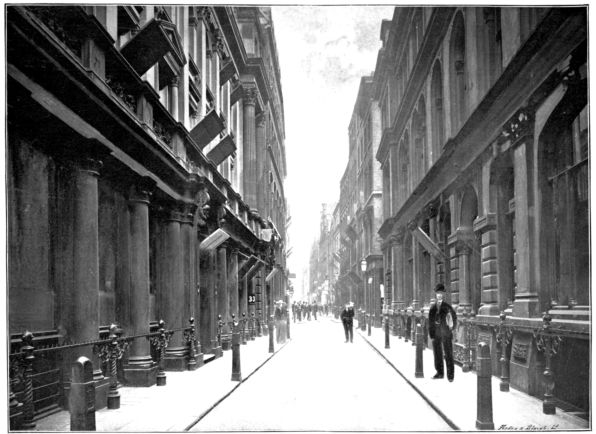

| Cannon Street, looking West | Facing | 250 |

| Old Merchant Taylors’ School, Suffolk Lane, Cannon Street | 254 | |

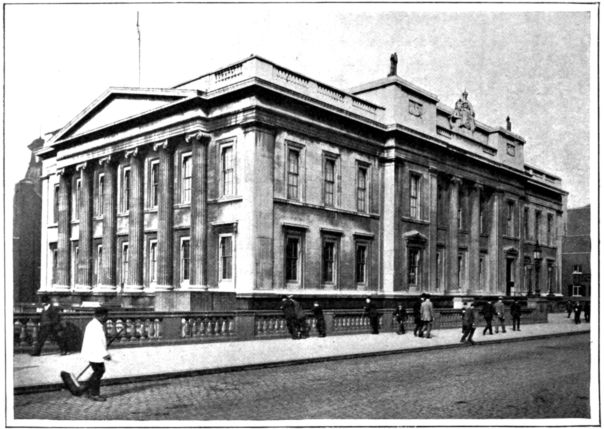

| Fishmongers’ Hall, present day | 260 | |

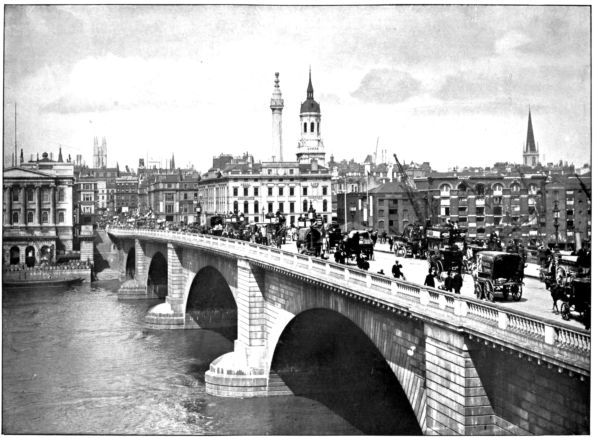

| London Bridge | Facing | 260 |

| Fishmongers’ Hall in 1811 | 261 | |

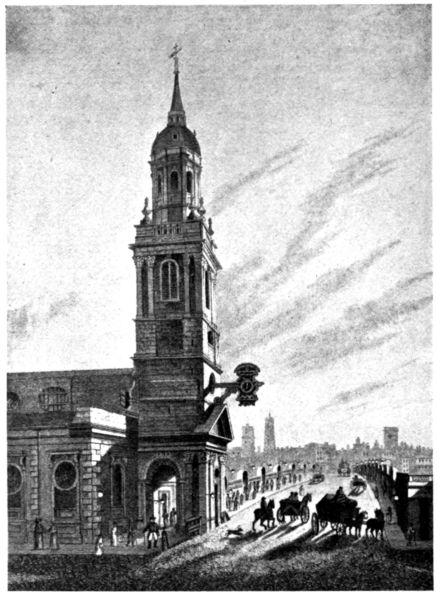

| St. Magnus | 262 | |

| The Monument in 1752 | 265 | |

| The Coal Exchange | 271 | |

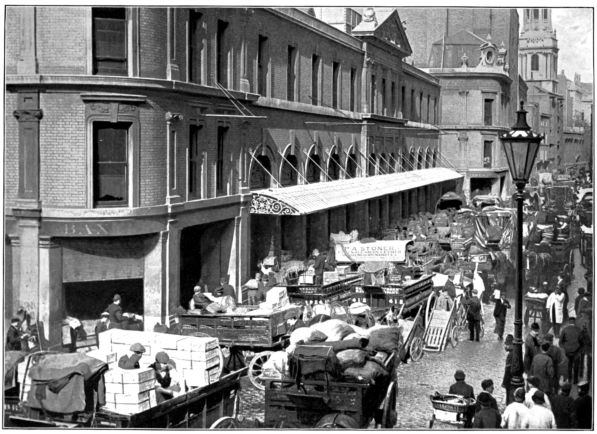

| Billingsgate Market | Facing | 272 |

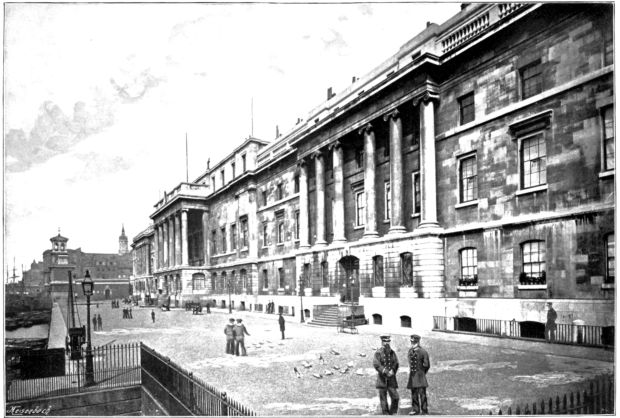

| Custom House | Facing | 274 |

| Clothworkers’ Hall | 277 | |

| Whittington’s House, Crutched Friars, 1796 | 279 | |

| Pepys’ Church (St. Olave, Hart Street) | 281 | |

| xiTrinity House, Tower Hill | 284 | |

| Remains of London Wall, Tower Hill, 1818 | 285 | |

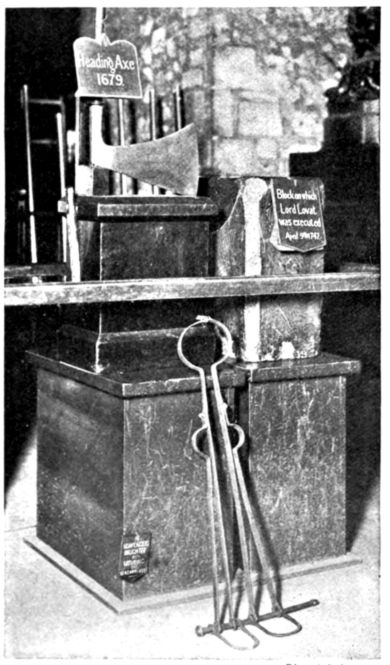

| Block, Axe, and Scavenger’s Daughter | 288 | |

| Newgate Market, 1856 | 304 | |

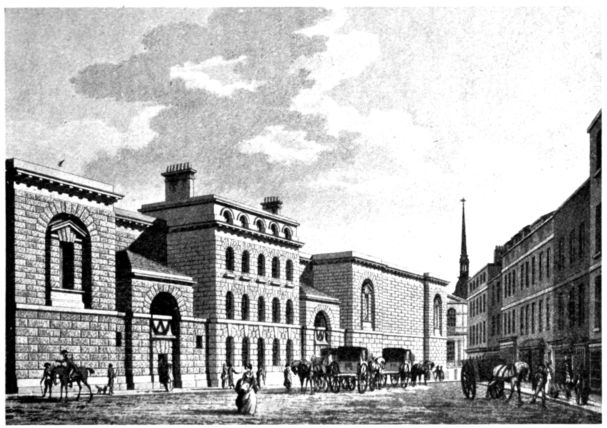

| Newgate, 1799 | 305 | |

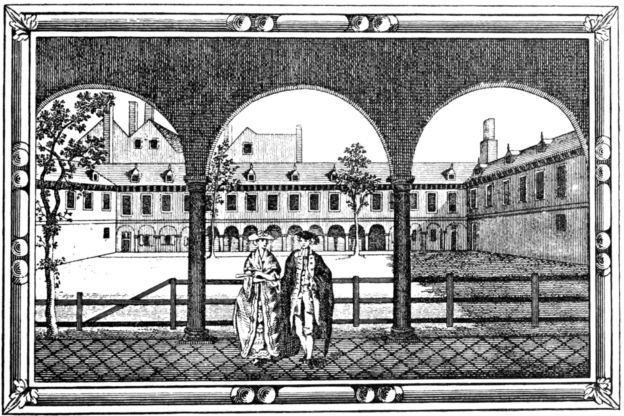

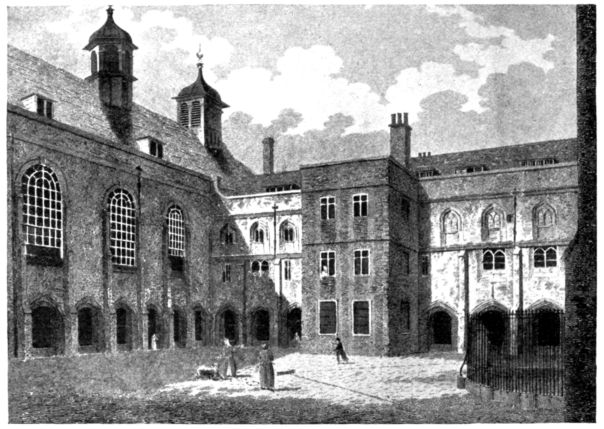

| Christ’s Hospital, from the Cloisters, 1804 | 308 | |

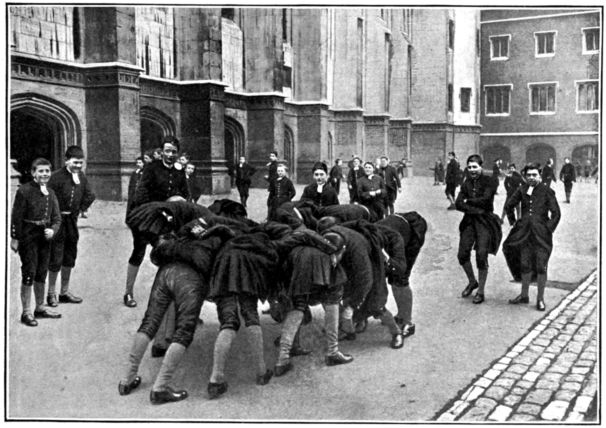

| An Exciting Game, Christ’s Hospital | 319 | |

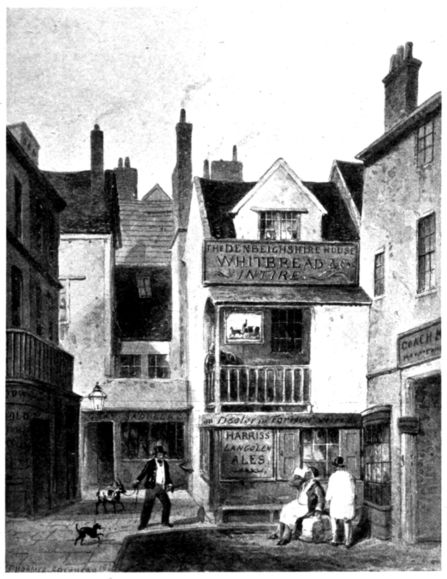

| The Oxford Arms, Warwick Lane | 323 | |

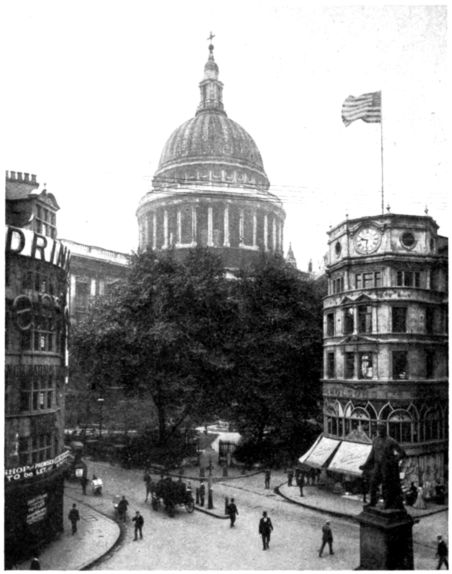

| The Post Office, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and Bull and Mouth Inn, London | 329 | |

| St. Paul’s Cathedral | 334 | |

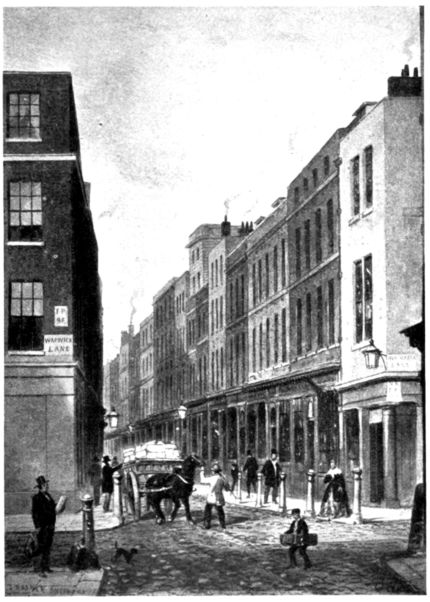

| Paternoster Row (as it was) | 343 | |

| Paternoster Row | Facing | 346 |

| The City Boundary, Aldersgate | 349 | |

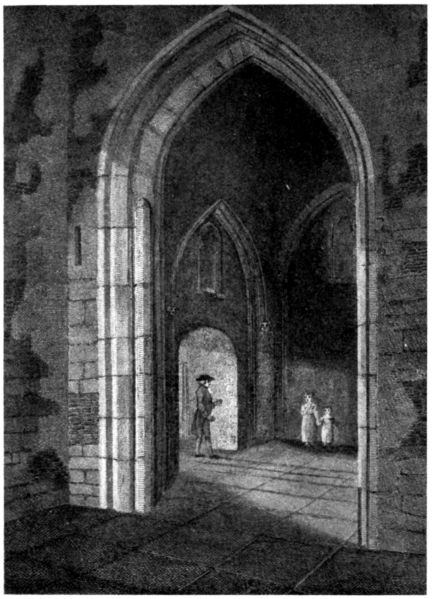

| St. Bartholomew the Great | 353 | |

| General Post Office | Facing | 354 |

| Cloth Fair | 356 | |

| Old Coach and Horses, Cloth Fair | 357 | |

| Long Lane, Smithfield, 1810 | 358 | |

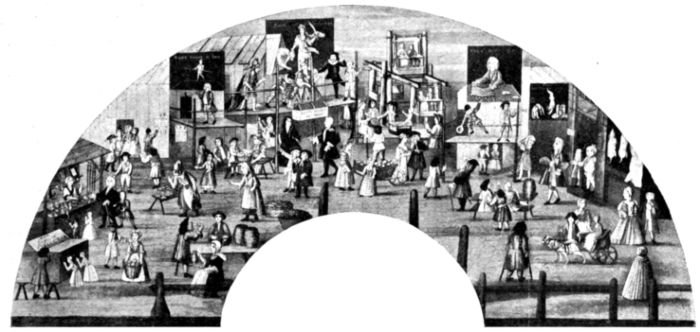

| Bartholomew Fair, 1721 | 359 | |

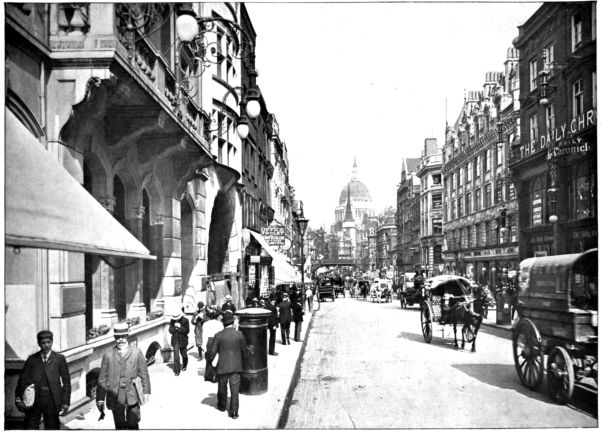

| Fleet Street | Facing | 364 |

| Izaak Walton’s House in Fleet Street | 366 | |

| St. Dunstan in the West (Old Church) | 368 | |

| Inner Temple Gate House | Facing | 374 |

| Supposed House of Dryden, Fetter Lane | 380 | |

| Dr. Johnson’s House | 381 | |

| Fleet Ditch, West Street, Smithfield, as it was in 1844 | 383 | |

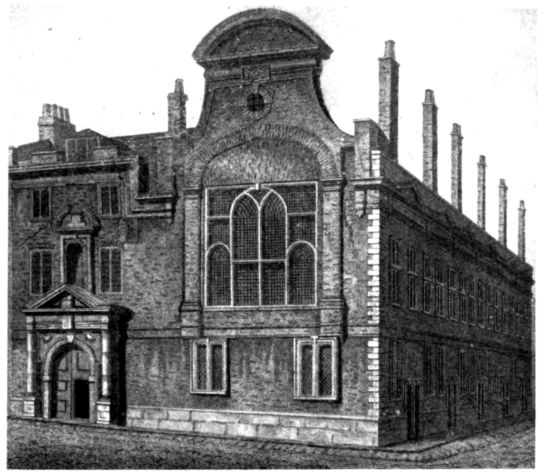

| St. Paul’s School (before its removal to Hammersmith) | 402 |

It seems convenient in treating of the history and archæology of the City to take the streets in groups, each group being in connection with the main street to which it belongs. We may in this fashion conveniently arrange the streets as follows:—

| (1) | Those north and south of Cheapside and the Poultry. |

| (2) | Those north of Gresham Street and west of Moorgate Street. |

| (3) | Those between Moorgate and Bishopsgate Streets. |

| (4) | Those between Fenchurch and Bishopsgate Streets. |

| (5) | Thames Street and the streets north and south of it. |

| (6) | Newgate Street and the streets north and south of it. |

| (7) | Fleet Street and the adjacent Courts (including the Temple and the Rolls). |

GROUP I

Cheapside.—We begin with the true heart of London, West Chepe, as it was formerly called, and the streets lying north and south of this marketplace. St. Paul’s Churchyard and Foster Lane mark our western boundary; Princes Street and Walbrook, our eastern; Gresham Street (formerly Cateaton Street) is on the north, and Cannon Street on the south.

By the time of Queen Elizabeth we find the West Chepe, with its streets north and south, laid out with something like the modern regularity. We must therefore go back to earlier centuries to discover its origin.

West Chepe, from time immemorial, has been the most important market of the City. It was formerly, say in the twelfth century, a large open area. This area contained no fewer than twenty-five churches, of which nine still exist. The churches are dotted about in apparent disorder, which can be partly explained. For the market of Chepe was extended in fact from the Church of St. Michael le Querne on the west, to that of St. Christopher le Stock on the east, and lay between the modern Gresham Street in the north and Watling Street in the south.

It is ordered in Liber Albus that all manner of victuals are to be sold between the kennels of the streets. The so-called streets were narrow lanes, many of which remain to the present day.

2There was, however, a principal way, not a street in our sense of the word, on either side of which, on the north and on the south, as well as along the middle, were stalls and shops. These stalls were at first mere wooden sheds; the goods were exposed by day and removed at night; in course of time they became permanent shops with living rooms at the back and an upper chamber. Among the sheds stood “selds.” The seld was a building not unlike the present Covent Garden Market, being roofed over and containing shops and store-houses. Several “selds” are mentioned in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. These were the “great-seld” in the Mercery, called after the Lady Roisia de Coventre. This was near the house of St. Thomas of Acon, where now stands the Mercers’ Hall. There was also the “great seld of London,” in the ancient parish of St. Pancras, therefore on the south side of Cheapside. There was again the “seld of Fryday Street serving for foreign tanners, and time out of mind occupied with these wares”; and there was a seld held in 1304 by John de Stanes, mercer.

In the Liber Albus the seld is distinguished from the “shop, the cellar or solar.” It is also alluded to in the same book as the place where wool and other commodities are sold. Bakers were forbidden to store their bread in selds longer than one night. The seld was therefore a warehouse, a weighing place, as well as a shop. Since we hear nothing about selds in the Calendar of Wills after the fourteenth century, we may infer that a change had been made in the methods of the market. The change in fact was this. North and south of what is now Cheapside were arranged in order the stalls of those who sold everything; these stalls were protected from the weather; the various branches or departments of the market were separated by narrow lanes. It is impossible at this time to assign all the various trades accurately each to its own place—in fact, they always overlapped; but we can do so approximately. The names of the streets belonging to Cheapside are a guide. For instance, Wood Street, Milk Street, Honey Lane, Ironmonger Street, Old Jewry, the Poultry, Scalding Alley, Soper Street, Bread Street, Friday Street, Old Change, explain a great part of the disposition of the ancient market.

When we consider that twenty-five churches stood in or about the great market, and that they were all presumably more ancient than the Conquest, we may deduce the fact that the stalls very early became closed shops, and in many cases permanent houses of residence, and that the market contained a large resident population by which industries were carried on as well as shops. With certain wares, such as milk, honey, wood, spices, mercery, salt-fish, poultry, meat, and herbs, there was no other industry than that of receiving, packing, and distributing. We therefore find few churches between Wood Street and Ironmonger Lane, the chief seat of these branches; while on the south side, for the same reason, there are still fewer churches.

3The South Chepe was occupied by money-changers, salt-fish dealers, leather-sellers, bakers, mercers, pepperers, and herb-sellers. Soap-makers were there also at one time, but they were banished to another part of the City before the time of Edward the Second. “Melters,” i.e. of lard and tallow, were also forbidden to carry on their evil-smelling trade in West Chepe so far back as 1203.

A brief study, therefore, enables us to understand, first, why the churches stand thickly in one part and thinly in another; next, that West Chepe was a vast open market containing a resident population, crowded where industries were carried on, and sparse where the goods were simply exposed for sale; and, thirdly, that the place could be easily converted into a tilting ground, as was done on many occasions, by clearing away the “stationers,” that is to say, the people who held stalls or stations about the crosses in Cheapside. On one occasion, at least, this was done, to the great indignation of the people.

There are certain places in the country, and on the Continent, where the mediæval market is still preserved in its most important features. For instance, there is the market-place of Peterborough, which is still divided by lanes, and which has areas allotted to the different trades; and that of Rheims, where the ancient usages are preserved and followed, even to the appearance of Autolycus, the Cheap Jack, and the Quack, who may be seen and heard on every market day.

We may take Stow’s description of the Elizabethan Chepe:

“At the West end of this Poultrie, and also of Bucklesbury, beginneth the large street of West Cheaping, a market place so called, which street stretcheth west till ye come to the little conduit by Paule’s gate, but not all of Cheape ward. In the east part of this street standeth the great conduit of sweet water, conveyed by pipes of lead underground from Paddington for the service of this city, castellated with stone, and cisterned in lead, about the year 1285, and again new built and enlarged by Thomas Ilam, one of the sheriffs 1479.

“About the midst of this street is the Standard in Cheape, of what antiquity the first foundation I have not read. But Henry VI., by his patent dated at Windsor the 21st of his reign, which patent was confirmed by parliament 1442, granted license to Thomas Knolles, John Chichele, and other, executors to John Wells, grocer, sometime mayor of London, with his goods to make new the highway which leadeth from the city of London towards the palace of Westminster, before and nigh the manor of Savoy, parcel of the Duchy of Lancaster, a way then very ruinous, and the pavement broken, to the hurt and mischief of the subjects, which old pavement then remaining in that way within the length of five hundred feet, and all the breadth of the same before and nigh the site of the manor aforesaid, they to break up, and with stone, gravel, and other stuff, one other good and sufficient way there to make for the commodity of the subjects.

4“And further, that the Standard in Cheape, where divers executions of the law beforetime had been performed, which standard at the present was very ruinous with age, in which there was a conduit, should be taken down, and another competent standard of stone, together with a conduit in the same, of new, strongly to be built, for the commodity and honour of the city, with the goods of the said testator, without interruption, etc.

“Of executions at the Standard in Cheape, we read, that in the year 1293 three men had their right hands smitten off there, for rescuing of a prisoner arrested by an officer of the city. In the year 1326, the burgesses of London caused Walter Stapleton, Bishop of Exceter, treasurer to Edward II., and other, to be beheaded at the standard in Cheape (but this was by Paule’s gate); in the year 1351, the 26th of Edward III., two fishmongers were beheaded at the standard in Cheape, but I read not of their offence; 1381, Wat Tyler beheaded Richard Lions and other there. In the year 1399, Henry IV. caused the blank charters made by Richard II. to be burnt there. In the year 1450, Jack Cade, captain of the Kentish rebels, beheaded the Lord Say there. In the year 1461, John Davy had his hand stricken off there, because he had stricken a man before the judges at Westminster, etc.

“Then next is a great cross in West Cheape, which cross was there erected in the year 1290 by Edward I. upon occasion thus:—Queen Elianor his wife died at Hardeby (a town near unto the city of Lincoln), her body was brought from thence to Westminster; and the king, in memory of her, caused in every place where her body rested by the way, a stately cross of stone to be erected, with the queen’s image and arms upon it, as at Grantham, Woborne, Northampton, Stony Stratford, Dunstable, St. Albones, Waltham, West Cheape, and at Charing, from whence she was conveyed to Westminster, and there buried.

“This cross in West Cheape being like to those other which remain to this day, and being by length of time decayed, John Hatherle, mayor of London, procured, in the year 1441, license of King Henry VI. to re-edify the same in more beautiful manner for the honour of the city, and had license also to take up two hundred fodder of lead for the building thereof of certain conduits, and a common granary. This cross was then curiously wrought at the charges of divers citizens: John Fisher, mercer, gave six hundred marks toward it; the same was begun to be set up 1484, and finished 1486, the 2nd of Henry VII.

“In the year 1599, the timber of the cross at the top being rotted within the lead, the arms thereof bending, were feared to have fallen to the harming of some people, and therefore the whole body of the cross was scaffolded about, and the top thereof taken down, meaning in place thereof to have set up a piramis; but some of her majesty’s honourable councillors directed their letters to Sir Nicholas Mosley, then mayor, by her highness’ express commandment concerning the cross, forthwith 5to be repaired, and placed again as it formerly stood, etc., notwithstanding the said cross stood headless more than a year after. After this (1600) a cross of timber was framed, set up, covered with lead, and gilded, the body of the cross downward cleansed of dust, the scaffold carried thence. About twelve nights following, the image of Our Lady was again defaced, by plucking off her crown, and almost her head, taking from her her naked child, and stabbing her in the breast, etc. Thus much for the cross in West Cheape” (Stow’s Survey, 1633, pp. 278-80).

CHEAPSIDE CROSS (AS IT APPEARED ON ITS ERECTION IN 1606).

From an original Drawing in the Pepysian Library, Cambridge.

The cross was the object of much abuse by the Puritans, who at last succeeded in getting it pulled down. “On May 2nd, 1643, the Cross of Cheapside was pulled down. A troop of horse and two companies of foot waited to guard it; and, at the fall of the top cross, drums beat, trumpets blew, and multitudes of caps were thrown 6into the air.... And the same day, at night was the leaden popes[1] burnt in the place where it stood, with ringing of bells and a great acclamation” (Wilkinson’s Londina Illustrata).

To continue Stow’s account:

“Then at the west end of West Cheape Street, was sometime a cross of stone, called the Old Cross. Ralph Higden, in his Policronicon, saith, that Walter Stapleton, Bishop of Exceter, treasurer to Edward II., was by the burgesses of London beheaded at this cross called the Standard, without the north door of St. Paul’s church; and so is it noted in other writers that then lived. This old cross stood and remained at the east end of the parish church called St. Michael in the Corne by Paule’s gate, near to the north end of the old Exchange, till the year 1390, the 13th of Richard II., in place of which old cross then taken down, the said church of St. Michael was enlarged, and also a fair water conduit built about the 9th of Henry VI.

“In the reign of Edward III., divers joustings were made in this street, betwixt Sopers lane and the great cross, namely, one in the year 1331, the 21st of September, as I find noted by divers writers of that time.

“In the middle of the city of London (say they), in a street called Cheape, the stone pavement being covered with sand, that the horses might not slide when they strongly set their feet to the ground, the king held a tournament three days together, with the nobility, valiant men of the realm, and other some strange knights. And to the end the beholders might with the better ease see the same, there was a wooden scaffold erected across the street, like unto a tower, wherein Queen Philippa, and many other ladies, richly attired, and assembled from all parts of the realm, did stand to behold the jousts; but the higher frame, in which the ladies were placed, brake in sunder, whereby they were with some shame forced to fall down, by reason whereof the knights and such as were underneath, were grievously hurt; wherefore the queen took great care to save the carpenters from punishment, and through her prayers (which she made upon her knees) pacified the king and council, and thereby purchased great love of the people. After which time the king caused a shed to be strongly made of stone, for himself, the queen, and other estates to stand on, and there to behold the joustings, and other shows, at their pleasure, by the church of St. Mary Bow, as is showed in Cordwainer street ward” (ibid.).

In 1754 Strype writes:

“Cheapside is a very stately spacious street, adorned with lofty buildings; well inhabited by Goldsmiths, Linen-Drapers, Haberdashers, and other great dealers. The street, which is throughout of an equal breadth, begins westward at Paternoster Row, and, in a straight line, runs to the Poultry, and from thence to the Royal exchange in Cornhill. And, as this Street is yet esteemed the principal high street 7in the City, so it was formerly graced with a great Conduit, a Standard, and a stately Cross; which last was pulled down in the Civil Wars. In the last Part, almost over-against Mercers Chapel, stood a great Conduit; but this Conduit, standing almost in the Middle of the street, being incommodious for Coaches and Carts, was thought fit by the Magistracy, after the great Fire, to be taken down, and built no more.”

The great Conduit of Chepe, commenced in 1285, brought the water from Paddington, a distance of 3½ miles. It stood opposite Mercers’ Hall and Chapel. It was a stone building long and low, battlemented, enclosing a leaden cistern. In the year 1441 at the west end of Chepe and in the east end of the Church of St. Michael le Querne, the smaller conduit was erected. Both conduits were destroyed in the Great Fire—the larger one was not rebuilt. The Standard opposite Honey Lane was in later years fitted with a water cock always running. At the Standard many public executions took place (Strype, vol. 1. p. 566).

Hardly any street of London is more frequently mentioned in annual documents than Chepe. There are many ancient deeds of sale and conveyances still preserved at the Guildhall, relating to property in Chepe. In the Calendar of Wills, houses, etc., in Chepe are bequeathed in more than two hundred wills there quoted; many ordinances concerning Chepe are recorded in Riley’s Memorials.

Stow has given some of the history of Chepe. His account may be supplemented by a few notes on other events and persons connected with the street.

The antiquity of the street is proved by the discovery of Roman coins, Roman tesserae, Romano-British remains of various kinds, and Saxon jewels. It is not, however, until the thirteenth century that we find historical events other than the conveyance, etc., of land and tenements in Cheapside.

In the thirteenth century a part of Cheapside, if not the whole, was called the Crown Field; the part so called was probably confined to a space on the east of Bow Church.

In the year 1232 we find the citizens mustering in arms at Mile End and “well arrayed” in Chepe.

In 1269 it is recorded that the pillory in Chepe was broken, and so remained for a whole year by the negligence of the bailiffs, so that nobody could be put in pillory for that time. The bakers seized the opportunity for selling loaves of short weight—even a third part short. But in 1270, on the Feast of St. Michael, the sheriffs had a new pillory made and erected on the site of the old one. Then the hearts of the bakers failed them for fear, and the weight of the loaves increased.

In 1273 the Mayor removed from Chepe all the stalls of the butchers and fishmongers, together with the stalls which had been let and granted by the preceding sheriffs, although the persons occupying them had taken them for life and had paid large sums for their leases. This was a political move, the intention being to deprive the stall-keepers of their votes. The Mayor, however, defended the 8action on the ground that the King was about to visit the City, and that it behoved him to clear the way of refuse and encumbrances.

In the year 1326 a letter was sent by the Queen and her son Edward calling upon the citizens of London to aid with all their power in destroying the enemies of the land, and Hugh le Despenser in especial. Wherefore, when the head of Hugh was carried in triumph through Chepe, with trumpets sounding, the citizens rejoiced.

In October of the same year when the Bishop of Exeter, Walter de Stapleton, was on his way to his house in “Elde Dean’s Lane” to dine there, he was met by the mob, dragged into Chepe with one of his esquires, and there beheaded. Another of the Bishop’s servants was beheaded in Chepe the same day.

On the birth of Edward III. on November 13, 1312, the people of London made great rejoicings, holding carols, i.e. dances and songs, in Chepe for a fortnight, while the conduits ran wine.

In 1482 a grocer’s shop in Cheapside with a “hall” over it—perhaps a warehouse—was let for the rental of £4 : 6 : 8 per annum. The owner of the shop was Lord Howard, created Duke of Norfolk in 1483.

References to Cheapside multiply as we approach more modern times. In 1522, when Charles V. came to England, lodgings were appointed for his retinue. Among them was a house in Cheapside, a goldsmith’s. It contained one parlour, one kitchen, one chamber, and one bed. The murder of Dr. Lambe in 1631, the execution of William Hacket in 1591, the burning of the Solemn Covenant in 1661,—these are incidents in the history of Cheapside. Many other events belonging either to the history of the City or of the realm have been mentioned elsewhere.

In the sixteenth century one of the sights of London was the Goldsmiths’ Row, built in 1491 on the site of certain shops and selds. Stow calls the Row “a most beautiful frame of faire houses and shops consisting of ten faire dwellinghouses and fourteen shops, all in one frame, builded foure stories high, beautified towards the street with the Goldsmith’s Arms and the likeness of woodmen, in memory of his name, riding on monstrous beasts all richly painted and gilt.” Maitland, who certainly could not remember it, says that it was “beautiful to behold the glorious appearance of the Goldsmith’s shops in the South row of Cheapside, which in a course reached from the Old Change of Bucklersbury exclusive of four shops only, of three trades, in all that space.”

Coming now to a description of Cheapside as it is at present, we find a statue of Sir Robert Peel standing on a block of granite. The whole is more than 20 feet in height. The statue was put up in 1855, and on the pedestal is the inscription of Peel’s birth and death. On the north of Cheapside is a large stone block of building in one uniform style with shops on the ground floor. This contains the Saddlers’ Hall, and in the middle is the great entrance way solidly carried out in stone.

THE SADDLERS COMPANY

The date of the formation of the Company, and the circumstances under which it was founded, are unknown. It existed at a very remote period. There is now preserved in the archives of the Collegiate Church of Saint Martin’s-le-Grand a parchment containing a letter from that foundation, in which reference is made to the then ancient customs of the Guild. This document is believed to have been written about the time of Henry II., Richard I., or John, most probably in the first of these reigns. In this letter reference is made to “Ernaldus, the Alderman of the Guild.” This Ernaldus is stated by Mr. Alfred John Kempe, in his work Historical Notices of the Collegiate Church of Saint Martin’s-le-Grand, to have lived before the Conquest, by which it may be inferred that the Company is of Anglo-Saxon origin.

King Edward I., A.D. 1272, granted a charter. King Edward III., by his charter 1st December, 37 Edward III., A.D. 1363, granted that as well in the City of London as in every other city, borough, or town where the art of Saddlers is exercised, one or two honest and faithful men of the craft should be chosen and appointed by the Saddlers there dwelling to superintend and survey the craft. This charter was exemplified and confirmed by Henry VI., Henry VII., and Henry VIII.

Richard II., by charter 20th March, 18 Richard II., A.D. 1374, granted to the men of the mystery of Saddlers of the City of London, that for the good government of the mystery they may have one commonalty of themselves for ever, and that the men of the same mystery and commonalty may choose and appoint every year four keepers of the men of the commonalty to survey, rule, and duly govern the same. Furthermore, that the keepers and commonalty, and their successors, may purchase lands, to the yearly value of twenty pounds, for the sustentation of the poor, old, weak and decayed persons of the mystery, and this charter was exemplified, ratified, and confirmed by Edward IV.

Queen Elizabeth, by charter 9th November, 1 Elizabeth, A.D. 1558, exemplifies, ratifies, and confirms the previous charters, and reincorporates the Company by the name of the wardens or keepers and commonalty of the mystery or art of Saddlers of the City of London. The charter names and appoints four wardens to hold office from the date of the charter until the 14th August then following, and authorises them to keep within their common hall an assembly of the wardens or keepers or freemen of the same mystery, or the greater part of them, or of the wardens, and of eight of the most ancient and worthy freemen, being of the assistants of the mystery, and that the wardens and eight of the assistants at least being present shall have full power to treat, consult, and agree upon the articles and ordinances touching the mystery or art aforesaid, and the good rule, state, and government of the same. Power is given to elect four wardens on the 14th August yearly. Power of giving two votes is given to the master at doubtful elections. Powers are also given for the government and regulation of the trade.

This is one of the most ancient, as it is also one of the most interesting, of the City Companies. Their original quarter was at St. Martin’s-le-Grand. The saddle played an important part in every man’s life at a time when riding was the only method of travelling.

The saddlers were connected with the Church of St. Martin’s-le-Grand and made some kind of convention with the Canons, the nature of which is uncertain. Probably the Canons promised them their aid in support of their rights and privileges, in return for which their religious gifts and fees were paid to the Church of St. Martin. The mystery of saddlery, like all others, overlapped, and encroached upon, other mysteries and crafts. Then there followed quarrels. Thus in 1307 (Riley, Memorials, p. 156) there was an affray between the saddlers on one side and the loriners, joiners, and painters on the other, on account of such encroachments. The quarrel was adjusted by the Mayor and Aldermen. Another trouble to which so great a trade was liable, was the desire of the journeymen to break off into fraternities of their own. This pretension was seriously taken in hand in 1796, and such fraternities were strictly forbidden.

The Company has had three halls, all on the same site. The first was burned in the Great Fire; the second in 1822; the present hall was built after the second fire, and is at No. 141 Cheapside.

At the corner of Wood Street is what remains of the churchyard of St. Peter’s, Westcheap, the building of which was destroyed in the Great Fire: a railed-in 10space, gravel covered and uninteresting, except for the magnificent plane-tree which spreads its branches protectingly over the low roofs in front. On the walls of the old houses near are fixed two monuments, and a little stone tablet rather high up, with the inscription:

followed by the names of the churchwardens.

The Church of St. Peter, Westcheap, was also called SS. Peter and Paul. After the Great Fire its parish was annexed to that of St. Matthew, Friday Street. The earliest date of an incumbent is 1302.

The patronage of the church was in the hands of the Abbot of St. Alban’s before 1302. Henry VIII. seized it and granted it in 1545 to the Earl of Southampton, in whose successors it continued up to 1666.

Houseling people in 1548 were 360.

A chantry was founded here at the Altar of the Blessed Virgin Mary by Nicholas de Faringdon, Mayor of London, 1313 and 1320, for himself and Rose his wife, to which Lawrence Bretham de Faversham was admitted chaplain, October 24, 1361; the endowment fetched £29 : 3 : 4 in 1548, when Sir W. Alee was priest. There was another at the Altar of the Holy Cross.

Sir John Munday, goldsmith, Mayor, was buried here in 1527; also Sir Alexander Avenon, Mayor in 1569; and Augustine Hind, clothworker, Alderman, and Sheriff of London, who died in 1554.

The only charitable gifts recorded by Stow are: £2 : 4 : 4, the gift of Sir Lionel Ducket; 3s. 4d., the gift of Lady Read; 7s. 6d., the gift of Mr. Walton.

John Gwynneth, Mus. Doc. and author, was rector here in 1545; also Richard Gwent, D.D., and William Boleyn, Archdeacon of Winchester.

ST. MARY-LE-BOW

But the ornament of Cheapside is St. Mary-le-Bow, which derived its additional name from its stone “bows” or arches. The date of its foundation is not known, but it appears to have been during or before the reign of William the Conqueror. The court of the Archbishop of Canterbury was held here before the Great Fire; and though the connection between the church and the ecclesiastical courts has ceased, it is still used for the confirmation of the election of bishops. The “Court of Arches” owes its name to the fact that it was held in the beautiful Norman crypt which still survives. The church has been made famous, Stow observes, as the scene of various calamities, of which he records details. In 1469 the Common Council ordained the ringing of Bow Bell every evening at nine o’clock, but the practice had existed for already more than a century; in 1515 the largest of the five bells was presented by William Copland. The church was totally destroyed in 1666, as well as those of St. Pancras, Soper Lane and Allhallows, Honey Lane; the two last were not rebuilt, their parishes being annexed to St. Mary’s. Wren began building the present church in 1671 and completed it in 1680. The cost was greater than any other of Wren’s parish churches by £3000, £2000 of which was contributed by Dame Williamson. The steeple was repaired by Sir William Staines in the eighteenth century, and again in 1820 by Mr. George Gwilt. In 1758, seven of the bells were recast, new ones were added, and the ten were first rung in 1762 in honour of George III.’s birthday; the full number now is twelve. In 1786 the parish of Allhallows, Bread Street, was united with this.

The earliest date of an incumbent is 1242.

The patronage of the church has always been in the hands of the Archbishop of Canterbury and his successors, but Henry III. presented to it in 1242.

Houseling people in 1548 were 300.

The church measures 65 feet in length, 63 feet in breadth, and 38 feet in height; it contains a nave 11and two side aisles. The great feature of the building is the steeple, which is the most elaborate of all Wren’s works and only exceeded in height by St. Bride’s. It rises at the north-west end of the church and measures 32 square feet at the base. The tower contains three storeys. The highest is surmounted by a cornice and balustrade with finials and vases, and a circular dome supporting a cylinder, lantern, and spire. The weather-vane is in the form of a dragon, the City emblem. The total height is 221 feet 9 inches. The Norman crypt already mentioned still remains, consisting of three aisles formed by massive columns; it probably formed part of the building in William I.’s time.

Chantries were founded here:

By John Causton, to which John Steveyns was admitted chaplain, December 2, 1452; by John Coventry, in the chapel of St. Nicholas; by Henry Frowycke, whose endowment fetched £15 : 10s. in 1548; by John de Holleghe, whose endowment produced £7 in 1548; by Dame Eleanor, Prioress of Winchester, whose endowment yielded £4 in 1548.

The original church does not appear to have contained many monuments of note. Among the civic dignitaries buried here was Nicholas Alwine, Lord Mayor in 1499, whose name is familiar to readers of The Last of the Barons.

Sir John Coventry, Mayor in 1425, was also buried here.

There is a tablet fixed over the vestry-room door, commemorating Dame Dionis Williamson, who gave £2000 towards the building of the church. On the west wall a sarcophagus commemorates Bishop Newton, rector, who won celebrity by his edition of Milton first published in 1749.

The parish possessed a considerable number of charities and gifts:

George Palin was donor of £100, to be devoted to the maintenance of a weekly lecture.

Mr. Banton, of £50 for the same purpose. There were others, to the total amount of £60.

There was one Charity School belonging to Cordwainer and Bread Street Wards for fifty boys and thirty girls, who were put to employments and trades when fit.

The following are among the notable rectors:

Martin Fotherby (d. 1619), Bishop of Salisbury; Samuel Bradford (1652-1731), Bishop of Gloucester; Samuel Lisle (1683-1749), Bishop of Norwich; Nicholas Felton (1556-1626), Bishop of Bristol; Thomas Newton (1704-1782), Bishop of Bristol; and William Van Mildert (1765-1836), Bishop of Llandaff, and later the last Prince-Bishop of Durham.

Quaint sayings and traditions have gathered more thickly about St. Mary’s than about any of the City churches. Dick Whittington’s story has made the name familiar to every British child; while to be born “within sound of Bow Bells” is more dignified than to own oneself a Cockney. In sooth-saying we have the prophecy of Mother Shipton that when the Grasshopper on the Exchange and the Dragon on Bow Church should meet, the streets should be deluged with blood. They did so meet, being sent to the same yard for repair at the same time, but the prophecy was not fulfilled.

The ringing of the Bow bells in the Middle Ages signified closing-time for shops, and the ringer incurred the wrath of the apprentices of Chepe if he failed to be punctual to the second.

We now proceed to the Poultry.

Stow thus describes the place:

“Now to begin again on the bank of the said Walbrooke, at the east end of the high street called the Poultrie, on the north side thereof, is the proper parish church of St. Mildred, which church was new built upon Walbrooke in the year 121457. John Saxton their parson gave thirty-two pounds towards the building of the new choir, which now standeth upon the course of Walbrooke.”

Strype says of it:

“The Poultry, a good large and broad Street, and a very great thoroughfare for Coaches, Carts, and foot-passengers, being seated in the Heart of the City, and leading to and from the Royal Exchange; and from thence to Fleet Street, the Strand, Westminster, and the western parts: and therefore so well inhabited by great tradesmen. It begins in the West, by the old Jewry, where Cheapside ends, and reaches the Stocks market by Cornhill. On the North side is Scalding Alley; a large place, containing two or three Alleys, and a square Court with good buildings, and well inhabited; but the greatest part is in Bread Street Ward, where it is mentioned.”

Roman knives and weapons have been found in the Poultry. The valley of the Walbrook, 130 feet in width, began its slope here. Nearly opposite Princes Street, a modern street, there was anciently a bridge over the stream. We find in the thirteenth century an inquest held here over the body of one Agnes de Golden Lane, who was found starved to death, a rare circumstance at that time, and only possible, one would think, considering the charity of the monastic houses, in the case of a bedridden person forgotten or deserted by her own people. In the fourteenth century there are various bequests of shops and tenements in the Poultry. In the fifteenth century we find that there was a brewery here, near the Compter; how did the brewer get his water? In the same century the Compter—which was one of the two sheriffs’ prisons—seems to belong to one Walter Hunt, a grocer. In the sixteenth century one of the rioters of 1517 was hanged in the Poultry; there was trouble about the pavements and complaints were made of obstructions by butchers, poulterers, and the ancestors of the modern coster, who sold things from barrows, stopping up the road and refusing to move on. Before the Fire there were many taverns in the Poultry; some of them had the signs which have been found belonging to the Poultry.

The later associations of the place have been detailed by Cunningham:

“Lubbock’s Banking-house is leased of the Goldsmiths, being part of Sir Martin Bowes’s bequest to the Company in Queen Elizabeth’s time. The King’s Head Tavern, No. 25, was kept in Charles II.’s time by William King. His wife happening to be in labour on the day of the King’s restoration, was anxious to see the returning monarch, and Charles, in passing through Poultry, was told of her inclination, and stopped at the tavern to salute her. No. 22 was Dilly, the bookseller’s. Here Dr. Johnson met John Wilkes at dinner; and here Boswell’s life of Johnson was first published. Dilly sold his business to Mawman. No. 31 was the shop of Vernor and Hood, booksellers. Hood of this firm was father of the facetious Tom Hood, and here Tom was born in 1798” (Hand-book of London).

13Here is a little story. It happened in 1318. One John de Caxtone, furbisher by trade, going along the Poultry—one charitably hopes that he was in liquor—met a certain valet of the Dean of Arches who was carrying a sword under his arm, thinking no evil. Thereupon John assaulted him, apparently without provocation, and drawing out the sword, wounded the said valet with his own weapon. This done, he refused to surrender to the Mayor’s sergeant, nor would he give himself up till the Mayor himself appeared on the spot. We see the crowd—all the butchers in the Poultry collected together: on the ground lies the wounded valet, bleeding, beside him is the sword, the assailant blusters and swears that he will not surrender, the Mayor’s sergeant remonstrates, the crowd increases, then the Mayor himself appears followed by other sergeants, a lane is made, and at sight of that authority the man gives in. The sergeants march him off to Newgate, the crowd disperses, the butchers go back to their stalls, the women to their baskets, the costers to their barrows. For five days the offender cools his heels at Newgate. Then he is brought before the Mayor. He throws himself on the mercy of the judge, sureties are found for him that he will keep the peace, and he consents to compensate the wounded man.

For Stocks Market, St. Mary Woolchurch Haw, on the site of which the Mansion House stands, and the vicinity, formerly included in the Poultry, see Group III.

At the east end of the Poultry is Grocers’ Alley, formerly Conyhope Lane, of which Stow says:

“Then is Conyhope Lane, of old time so called of such a sign of three conies hanging over a poulterer’s stall at the lane’s end. Within this lane standeth the Grocers’ hall, which company being of old time called Pepperers, were first incorporated by the name of Grocers in the year 1345.” The Grocers’ Hall really opens into Princes Street.

THE GROCERS COMPANY

The Company’s records begin partly in Norman-French, partly in Old English, as follows: “To the honour of God, the Virgin Mary, St. Anthony and All Saints, the 9th day of May 1345, a Fraternity was founded of the Company of Pepperers of Soper’s Lane for love and unity to maintain and keep themselves together, of which Fraternity are sundry beginners, founders, and donors to preserve the said Fraternity.”

(Here follow twenty-two names.)

The same twenty-two persons “accorded to be together at a dinner in the Abbot’s Place of Bury on the 12th of June following, and then were chosen two the first Wardens that ever were of our Fraternity,” and certain ordinances were agreed to by assent among the Fraternity, providing that no person should be of the Fraternity “if not of good condition and of this craft, that is to say, a Pepperer of Soper’s Lane or a Spicer in the ward of Cheap, or other people of their mystery, wherever they reside”; for contributions among the members, for the purposes of the Fraternity, including the maintenance of a priest; the wearing of a livery; arbitration by the Wardens upon disputes between members; attendance at Mass at the Monastery of St. Anthony on St. Anthony’s Day, and at a feast on that day or within the octave, at which feast the Wardens should come with chaplets and choose and crown two other Wardens for the year ensuing; attendance at the funerals of members; the taking of apprentices; assistance of unfortunate 14members out of the common stock; and that “any of the Fraternity may according to his circumstance and free will devise what he chooses to the common box for the better supporting the Fraternity and their alms.”

From external evidence it appears that for two centuries at least before 1345 there had existed a Guild of Pepperers, who had superseded the Soapers in Soper’s Lane, and probably absorbed them. The twenty-two Pepperers, who in 1345 founded the social, benevolent, and religious fraternity of St. Anthony, were of “good condition,” probably the most influential and wealthy men in the Pepperers’ guild; in founding the new brotherhood “for greater love and unity” and “to maintain and assist one another,” they did not desert their old guild, but formed a new fraternity within it. They did not seek, apparently, to alter the institution of the Guild of Pepperers, nor did they adopt a distinctive title for themselves; but the movement was obviously an important one, and attracted notice and jealousy, which was perhaps increased by the foreign connections of some of the members. So rapidly did the Company gain favour and strength that in 1383, not forty years after its foundation, there were one hundred and twenty-nine liverymen of whom not less than sixteen were Aldermen. At that time, no doubt, the Company exercised a preponderating influence in the City of London.

The new brotherhood was styled the Fraternity of St. Anthony from 1348 to 1357. After this year there is an hiatus in the Company’s records, and when these recommence in 1373 the title is “company” or “fraternity” of “gossers,” “grosers,” “groscers,” or “grocers.”

The origin of the term “grocer” and its application to the Company are involved in considerable obscurity. As far as can be ascertained, the first use of the word, officially, is against the Company from without, and in an aspect of reproach. It occurs in a petition to the King and Parliament in 1363, against the new fraternity that “les Marchantz nomez Grossers engrossent toutes maneres de marchandises vendables.”

It is by no means improbable that the term, first suggested by less successful rivals in trade, was adopted by the leading dealers “en gros” for the name of the company, which formed round the Fraternity of St. Anthony, and probably absorbed the whole Guild of Pepperers.

From this time forward the Company began to act with energy in the interests of trade. In 1394 we find them, together with some Italian merchants, presenting a petition to the Corporation complaining of the unjust mode of “garbling,” i.e. cleansing or purifying spices and other “sotill wares.” The petition was entertained, and the Company were requested to recommend a member of their own body to fill the office, and on their nomination Thomas Halfmark was chosen and sworn garbeller of “spices and sotill ware.”

The fraternity, after holding their meetings for three years at the Abbot of Bury’s, assembled in 1348 at Fulsham’s house at the Rynged Hall, in St. Thomas Apostle, close to St. Anthony’s Church in Budge Row, Watling Street, where they at this time obtained permission to erect a chantry, etc., and called themselves the Fraternity of St. Anthony. They ultimately collected at Bucklersbury (“Bokerellesbury”), at the Cornet’s Tower, which had been used by Edward III. at the beginning of his reign as his exchange of money and exchequer. Here the Company began to exercise the functions entrusted to them of superintending the public weighing of merchandise.

In 1411 a descendant of Lord FitzWalter, who, in the reign of Henry III., had obtained possession of the chapel of St. Edmund which adjoined his family mansion, sold the chapel to the Company for 320 marks, and in the next reign the Company purchased the family mansion and built their Hall upon the site. The foundation stone was laid in 1427 and the building was completed in the following year. The expenses were defrayed by the contributions of members. Five years later the garden was added.

In 1428 the Company’s first charter of incorporation was granted by King Henry VI., and they became a body politic by the name of “Custodes et Communitas Mysterii Groceriæ Londini.” Nineteen years later the same king granted to the Company the exclusive right of garbling throughout all places in the kingdom of England, except the City of London.

In 1453 the Company, having the charge and management of the public scale or King’s Beam, made a regular tariff of charges. It appears that to John Churchman, grocer, who served the office of sheriff in 1385, the trade of London is indebted for the establishment of the first Custom House. 15Churchman, in the sixth year of Richard II., built a house on Woolwharf Key, in Tower Street Ward, for the tronage or weighing of wools in the port of London, and a grant of the right of tronage was made by the King to Churchman for life. It is probable that Churchman, being unable of himself to manage so considerable a concern as the public scale, obtained the assistance of his Company, and thus the management of the weigh-house and the appointment of the officers belonging to it came into the hands of the Grocers Company.

Henry VIII. granted to the City of London the Beam with all appurtenances, and directed its management to be committed to some expert in weights. The City thereupon gave the management to the Company, only requiring one-third of the profits. The Company enjoyed, uninterruptedly, these privileges up to 1625, when a dispute arose with the City, and an agreement was made whereby the Company were to appoint four under-porters, and present four candidates for Master Porter, the Lord Mayor to choose one of them. Several disputes followed with the Corporation, who in 1700 ejected the officers appointed by the Company, and tried their right at law. No result is reported, but the Company filled up vacancies after that date, and up to 1797, when a Bill was passed for making Wet Docks at Wapping, and this appears to have had the effect of depriving the Company of their privileges.

The Company throughout this period kept, in common with others, a store of corn, according to ancient custom, for the supply of the poor at reasonable prices when bread was dear.

The Company was also bound to maintain an armoury at their Hall.

At the time of the Great Plague in 1665 the Company were assessed in various sums of money for the relief of the poor, and they also provided a large quantity of coals.

The next year the Great Fire of London inflicted losses on the Company from which it did not recover for nearly a century. The Company’s Hall and all the adjacent buildings (save the turret in the garden, which fortunately contained the records and muniments of the Company) and almost all the Company’s houses were destroyed. The silver recovered from the ruins of the Hall was remelted and produced nearly 200 lbs. weight of metal; this was sold for the Company’s urgent present necessities. In 1668 Sir John Cutler came forward and proposed to rebuild the parlour and dining-room at his own charge. In the same year ninety-four members were added to the Livery. The next year a petition was presented to Parliament praying for leave to bring in a Bill to raise £20,000 by an equal assessment upon the members of the Company of ability. The application to Parliament failed, and an effort was then made to raise the £20,000 among the members, but only £6000 was subscribed.

In January 1671 a Special Court was summoned to consider a Bill exhibited in Parliament by some of the Company’s creditors, praying for an Act for the sale of the Company’s Hall, lands, and estates to satisfy debts; and to make members of the Court liable for debts incurred. A Committee was appointed and in 1672 the Hall was, at the instance of the Governors of Christ’s Hospital, sequestered, and the Company ejected till 1679, when, after great difficulties and impediments, money was borrowed to pay off the debts and get rid of the intruders. In 1680 the Court of Assistants agreed that the most effectual way of regaining public confidence was to rebuild the Hall.

In order to prevent a second sequestration an Inquisition was taken in 1680 before Commissioners for Charitable Uses, and, pursuant to a decree made by those Commissioners, a period of twenty years was allowed to the Company to discharge their debts. The next year, to secure an accession of influence and talent for the support of the Company, sixty-five members were added to the Court, and a number of Freemen were summoned, and eighty-one members added to the Livery.

In 1683 the Company arranged, by arbitration, their difficulties with the Governors of Christ’s Hospital, and their prospects appeared more hopeful when the celebrated Writ of Quo Warranto was issued by King Charles II. against the City charters and liberties. The Company, with the view of propitiating the King, by deed under seal, voluntarily surrendered the powers, franchises, privileges, liberties, and authorities granted or to be used or exercised by the Wardens and Commonalty, and the right of electing and nominating to the several offices of Wardens, Assistants, and Clerk of the Company, and besought his Majesty to accept their surrender. Charles II. obtained judgment upon the Quo Warranto against the City, and all the redress that the Company could obtain was the grant of another 16charter under such restrictions as the King should think fit. His successor, James II., with a view to secure the goodwill and support of the City, sent for the Lord Mayor and Aldermen, and voluntarily declared his determination to restore the City charters and liberties as they existed before the issuing of the Writ of Quo Warranto; and subsequently Judge Jeffreys came to Guildhall and delivered the charters with two grants of restoration to the Court of Aldermen.

The history of the Company during the eighteenth century is an account of pecuniary difficulties and the gradual extrication by the public spirit and foresight of the members.

As regards the profession or trade of the members, a return exists of the whole numbers for the year 1795 when the Court contained 32, the livery numbered 81, and the freemen 228. Of these, 40 were Grocers.

The number of the Livery returned in 1898 was 183. The Corporate Income was £37,500; the Trust Income was £500.

The advantages of being a member of the Company are as follows:

(1) Freemen are entitled to apply on behalf of their children for the Company’s presentations (six in number) to Christ’s Hospital; for the Company’s Scholarships for free education at the City of London School. The orphan children of freemen are alone eligible for the three presentations to the London Orphan Asylum.

Freemen are entitled to take apprentices.

Freemen, and widows and daughters of freemen, in needy circumstances may apply for relief, either temporary or permanent. Loans to freemen are practically abolished.

(2) Twelve months after a liveryman has been elected he is entitled, provided he live within twenty-five miles of the polling place, Guildhall, to be put upon the Register of Voters for the City, which entitles him to a vote at the election of Members of Parliament for the City; a liveryman is also entitled to vote at the election of the Lord Mayor and Sheriffs of London. The livery receive invitations from the Master and Wardens to the four public dinners in the months of November, February, May, and July, in each year, and at every fifth dinner an invitation for a friend as well.

In some years when the honorary freedom of the Company is bestowed on distinguished personages, there is an extra public dinner to which the livery are invited. At the public dinner in May, called the Restoration Feast, a box of sweetmeats is presented to every guest. Liverymen, and the widows and daughters of liverymen in needy circumstances may apply for relief, either temporary or permanent.

The Hall of the Company has always occupied the same site since the first erection in 1427, when the Wardens bought part of the demesne of Lord FitzWalter in Conyhope Lane.

This building perished in the Great Fire of 1666. A new hall was built, but in 1798-1802 this building was pulled down and rebuilt. Alterations and additions were made in 1827, when the present entrance into Princes Street was constructed. There were formerly three ways of access to the hall—one from the Old Jewry; one by the lane called Grocers’ Alley; and one by Scalding Lane from St. Mildred, Poultry, of which a scrap of the churchyard still remains. The two lanes opened on a small Place on the north side of which was Grocers’ Hall and on the south side the Poultry Compter.

The hall destroyed in 1666 would have become by this time historical as the place to which the Houses removed from Westminster in 1642 after the attempt to seize the five members on 4th January of that year. The Committee appointed by both Houses met first at Guildhall and adjourned to Grocers’ Hall to “treat of the safety of the Kingdoms of England and Ireland.” It was in this hall that the City entertained the Houses, June 17, 1645, in the midst of the Civil War, and on June 7, 1649, when the Civil War was over. For forty years, 1694-1734, the Grocers’ Hall was rented and occupied by the Governors and Company of the Bank of England.

The Company numbered among its members Charles II., James II., William III., the Earl of Chatham, William Pitt, George Canning, and many others.

In the eighteenth century, the “Lane” was chiefly occupied by houses called spunging houses; here persons were confined by the sergeants belonging to the 17Poultry Compter, so that they might come to some compromise with their creditors, and not be taken into prison. Hawkesworth, essayist and man of letters, was originally clerk to an attorney in this court. Boyse, the ragged poet, was confined in one of the spunging houses. Here he wrote the Latin letter to Cave:

The Alley led to an open court. In this open place in 1688 a cart-load of seditious books was burned.

The east side of the Place is at present occupied by one wall of the Gresham Life Assurance Society, a magnificent building facing Poultry. It has finely proportioned polished granite columns with Corinthian capitals adding strength to the frontage, and a balcony with parapet running horizontally across the front. This was rebuilt in 1879. It stands on the site of St. Mildred, Poultry.

The Church of St. Mildred, Poultry, was situated on the north side of the Poultry. It was rebuilt in 1456, and, after being destroyed by the Great Fire, again rebuilt in 1676, when the parish of St. Mary Colechurch was annexed. In 1872 it was taken down, and the parish joined to St. Olave, Jewry. The earliest date of an incumbent is 1247. The patronage of the church was in the hands of the Prior and Convent of St. Mary Overy, Southwark, 1325; Henry VIII., 1541, and so continued in the Crown.

Houseling people in 1548 were 277.

Chantries were founded here by Solomon Lanfare or Le Boteler, citizen and cutler, at the Altar of Blessed Virgin Mary, to which Wm. de Farnbergh was admitted chaplain, October 4, 1337; by Hugh Game, poulterer, who endowed it with rents, which fetched £10 in 1548, when John Mobe was priest; by John Brown, for himself, his wife, Margaret his daughter, and Giles Walden, etc., to which John de Cotyngham was admitted chaplain, April 6, 1366. One John Mymmes had licence from Richard II. to found the Guild of Fraternity of Corpus Christi here; the endowment fetched £10 : 8 : 8 in 1548, when John Wotton was priest thereof. Here was a “Little Chapell” valued at 60s. in 1548.

Thomas Ashehill was buried here; he gave great help in rebuilding the church about 1450; also Thomas Morstead, chirurgeon to Henry IV., V., and VI., and one of the sheriffs of London. In more recent times, Wm. Cronne was commemorated; he was a Fellow of the Royal Society and of the College of Physicians, and died in 1706.

A great number of benefactors are recorded by Stow, of which the most notable are: William Watson, of £100, whereof £65 was received; William Tudman, of £247 in all, for various charities; Sarah Tudman, of £80; Lady Elizabeth Allington, £200, towards rebuilding.

One free school is recorded, called Mercers’ School (Stow).

18John Williams (d. 1709), Bishop of Chichester, 1696, was rector here; also Benjamin Newcome, D.D., Dean of Rochester.

On the east side of Grocers’ Hall Court stood the Poultry Compter.

Strype describes the place and its government.

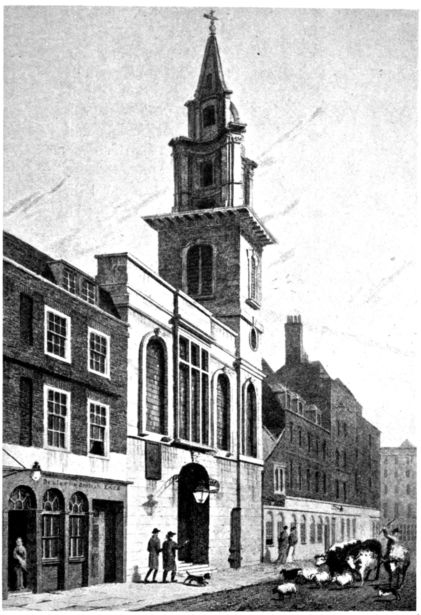

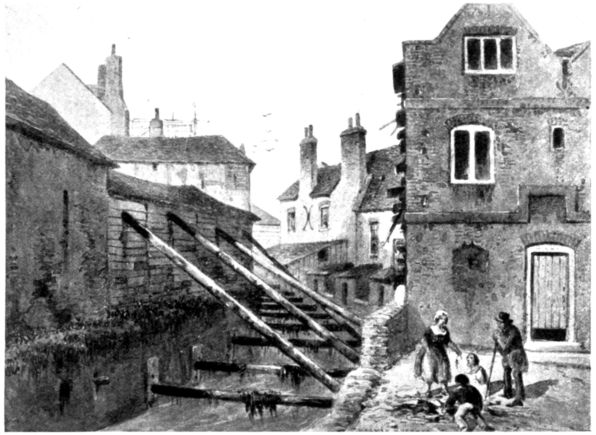

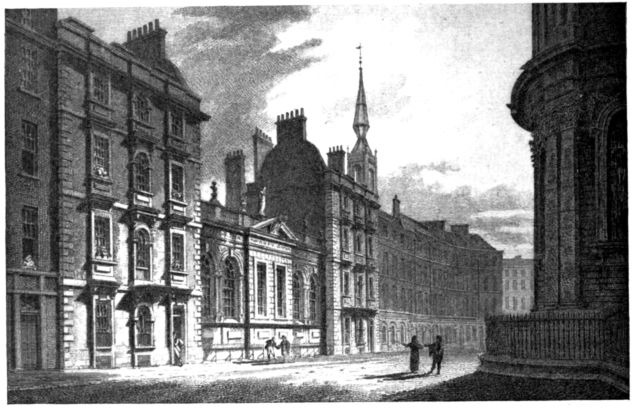

ST. MILDRED, POULTRY

“Somewhat west to this Church is the Poultry Compter, being the Prison belonging to one of the Sheriffs of London, for all such as are arrested within the City and liberties thereof. And, besides this Prison, there is another of the same Nature in Wood Street for the other Sheriff; both being of the same nature, and have the like officers for the Execution of the concerns belonging thereunto, as shall be here taken notice of. So that what is said here for Poultry Compter, belongs also to Wood Street Compter.

19“The Charge of those prisons is committed to the Sheriffs.

“Unto each Compter also belongs a Master Keeper; and under him two Turnkeys, and other servitors.

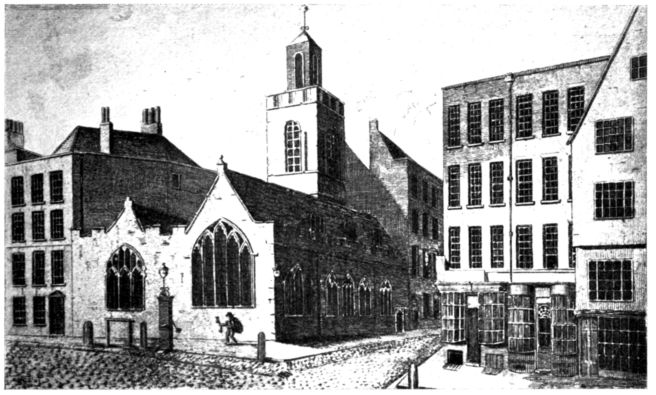

INSIDE THE POULTRY COMPTER

“The poorer sort of prisoners, as well in this Compter, as in that in Wood Street, receive daily relief from the sheriff’s table, of all the broken meat and bread. And there are divers gifts given by several well disposed people, towards their subsistence. Besides which, there are other benevolences frequently sent to all the prisons by charitable persons; many of which do conceal their names, doing it only for charity sake. And there are other gifts, some for the releasement of such 20as lie in only for prison fees; and others, for the release of such, whose debts amount not to above such or such a sum” (Strype, vol. i. p. 567).

This was the only prison in London with a ward set apart for Jews. “Here died Lamb, the conjuror (commonly called Dr. Lamb), of the injuries he had received from the mob, who pelted him (June 13, 1628), from Moorgate to the Windmill in the Old Jewry, where he was felled to the ground with a stone, and was thence carried to the Poultry Compter, where he died the same night. The rabble believed that the doctor dealt with the devil, and assisted the Duke of Buckingham in misleading the king. The last slave imprisoned in England was confined (1772) in the Poultry Compter. This was Somerset, a negro, the particulars of whose case excited Sharpe and Clarkson in their useful and successful labour in the cause of negro emancipation” (Cunningham’s Hand-book of London).

When Whitecross Street Prison (1815-1870) was erected, the prisoners were removed there from the Poultry, and the site of the Compter was built upon partly by a Congregational Chapel, the congregation of which removed to the Holborn Viaduct when the City Temple was built.

The prison was burned down in the Fire, whereupon the prisoners were taken to Aldgate until it was rebuilt. It was an ill-kept, unventilated, noisome place.

It is worthy of note that the earliest bequest to the Compter mentioned in the Calendar of Wills belongs to the fifteenth century, and that most of the legacies to the prisoners were made after the Reformation and in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. In some of them we find mention of the “Hole” and of the “Twopenny Ward.”

In 1378 there was an altercation between the Mayor and one of the sheriffs. Allusion is made to that sheriff’s “own compter” in Milk Street, which may be taken for that of Wood Street, as the Compter lay between the two, though it stood in Bread Street until the year 1555. In the year 1382 a sumptuary law was issued restricting the dress of women of loose life, and those who offended were to be taken to one of the Compters. In 1388 we find the porter of a Compter insulting Adam Bamme, alderman, for which he was removed from his office. We find also a householder taken to the Compter for refusing to pay his rates and abusing the collector. In 1413, an old man named John Arkwythe, a scrivener, was summoned by Alderman Sevenoke for allowing the escape of a certain priest caught in adultery in St. Bride’s Church. John Arkwythe lost his temper, clutched the Alderman by the breast and threatened him. They sent him to Newgate, but, considering his age, they let him go, only depriving him of the freedom of the City. In 1418, one William Foucher, for contempt of Court, was sent to solitary imprisonment in the Compter, and prohibited from speaking to any one except those who should counsel him repentance and amendment.

From these cases it would appear that the Compters were used partly as 21houses of detention before trial, and that trial was frequently deferred in order that the offender might endure a term of imprisonment in addition to the pillory, or the release on finding security, which would follow.

West of Grocers’ Alley is the Old Jewry, one of the most interesting places in the whole of London on account of its having been the Ghetto, though not a place of humiliation, for the Jews of London. When they came to London they received this quarter for their residence; why this place, so central, so convenient for the despatch of business, was assigned to them, no one has been able to discover. In the learned work of Mr. Joseph Jacobs (The Jews of Angevin England) he shows that Jews were in Oxford and Cambridge as well as in London in the time of the Normans.

The older name of the street was Colechurch Street. In the Receipts and Perquisites of the Tower from the Jews of London are found the following:

| For two pounds found in the Jewry for forfeit | 60s. |

[The sense of this entry is doubtful. Perhaps the two pounds were forfeited and 60 is wrongly transcribed for 40 (lx. for xl.).] (Guildhall MS. 129, vol. ii. p. 95a.)

| From a certain Christian woman found in the Jewry for the purpose of making an exchange. She fled and threw away the money | 100s. | (ibid. p. 97). |

| From a certain goldsmith fighting in the Jewry, of a fine | 21s. | (ibid. p. 96). |

| From Nicholas, the convert, goldsmith of London, for his boys fighting in the Jewry | 100s. | (ibid. p. 97). |

| From a certain Christian found in the Jewry by night | 7s. 11½d. | (ibid. p. 97). |

| From a certain boy coming into the Jewry | 66s. 8d. | (ibid. p. 97). |

| From John of Lincoln because he was found in the Jewry by night | £6 | (ibid. p. 97). |

| From a certain Christian woman in the Jewry by night | 18s. | (ibid. p. 97). |

It thus appears that the Jewry was walled in with gates. Had it been a simple street, a thoroughfare, there could have been no objection to any one passing through. As for the teaching of the Church respecting Jews, these extracts from Mr. Jacob’s book will show the hatred which was inculcated towards them.

“If any Christian woman takes gifts from the infidel Jews or of her own will commits sin with them, let her be separated from the church a whole year and live in much tribulation, and then let her repent for nine years. But if with a pagan let her repent seven years.

“If any Christian accepts from the infidel Jews their unleavened cakes or any other meat or drink and share in their impieties, he shall do penance with bread and water for forty days; because it is written ‘to the pure all things are pure.’

“It is allowable to celebrate mass in a church where faithful and pious ones have been buried. But if infidels or heretics or faithless Jews be buried, it is 22not allowed to sanctify or celebrate mass; but if it seem suitable for consecration, tearing thence the bodies or scraping or washing the walls, let it be consecrated if it has not been so previously.”

The earliest mention of the Jews occurs in the Terrier of St. Paul’s, 1115:

“In the ward of Haco ... in the Jew’s street (?Old Jewry) the land of Lusbert, in the front on the west side, is 32 feet in breadth. Towards St. Olave’s is fourscore and fifteen feet; again towards St. Olave’s is 65 feet, and in the front 13 feet. The land in the front is 73 feet, and in depth 41 feet, and pays 10s.”

In 1264, and again in 1267, the popular hatred of the Jews broke out with unmistakable violence. They fled to the Tower, while the mob destroyed and sacked their buildings.

In 1290 they were banished.

Their synagogue, which stood in the north-east corner of the present street, was given to the Fratres de Saccâ (see Mediæval London, vol. ii. p. 365), and on their dissolution it was ceded to Robert FitzWalter and converted into a merchant’s residence. Here lived and died Robert Large to whom Caxton was apprenticed.

The later history of the street may be quoted from Cunningham:

“The last turning but two on the east side (walking towards Cateaton Street) was called Windmill Court, from the Windmill Tavern, mentioned in the curious inventory of ‘Innes for Horses seen and viewed,’ preparatory to the visit of Charles V. of Spain to Henry VIII., in the year 1522. ‘From the Windmill,’ in the old Jewry, Master Wellbred writes to Master Knowell, in Ben Jonson’s play of Every Man in his Humour. Kitely, in the same play, was a merchant in the Old Jewry. The house or palace of Sir Robert Clayton (of the time of Charles II.), on the east side, was long a magnificent example of a merchant’s residence, containing a superb banquetting-room, wainscotted with cedar, and adorned with battles of gods and giants. Here the London Institution was first lodged; and here, in the rooms he occupied as librarian, Professor Porson died (1808). Dr. James Foster, Pope’s ‘modest Foster’—

was a preacher in the Old Jewry for more than twenty years. He first became popular from Lord Chancellor Hardwicke stopping in the porch of his chapel in the Old Jewry, to escape from a shower of rain. Thinking he might as well hear what was going on, he went in, and was so well pleased that he sent all his great acquaintances to hear Foster.”

Alexander Brown, the cavalier song-writer, was an attorney in the Lord Mayor’s Court in this street, and Bancroft, who built the almshouses of Mile End, was an officer in the court. Sir Jeffrey Bullen, Lord Mayor, 1457, lived in this street, where he was a mercer.

23In the fifteenth century there was standing in Old Jewry, north of St. Olave’s Church, and extending to the north end of Ironmonger Lane and down the lane as far as St. Martin’s Church, a large building of stone “very ancient,” the history and purpose of which were unknown except that Henry VI. appointed one John Stert, keeper of the place, which he called his principal palace in the Old Jewry. It was standing when Stow was a boy, but he says the outward stone-work was little by little taken down, and houses built upon the site. It was known as the Old Wardrobe. I know of no other reference to this place, but one would like to learn more. The taking away of the stone “little by little” accounts in like manner for the gradual disappearance of the ruins of the monastic houses.

The modern street is not of much interest. The City Police Office is in a court of some size near the north end. The Old King’s Head is in an elaborate building faced with red sandstone, and a grimy blackened old brick house close by contains the Italian Consulate.

In Frederick Place are two rows of Georgian houses in dull brick, varying only slightly in detail. The iron link-holders of a past fashion still survive on the railings before some of the houses. No. 8, at the south-eastern corner, contains some curious and interesting mantels. One of these has a central panel representing a boar hunt; this is in relief enclosed in a large oval. There are fine details also in other fireplaces in the house.

But these are not the only objects of interest in Frederick Place, for in exactly the opposite corner, the north-west, in a house numbered 4, are one or two fireplaces which surpass these in beauty if not in quaintness. In one of the rooms there is a very high and well-proportioned white marble mantelpiece, with singularly little decoration, which is yet most effective. All these houses are now used as offices by business men, and the evidences of bygone domestic occupation add a human interest to the daily routine.

St. Mary Colechurch was situated in the Poultry at the south-west corner of the Old Jewry. It was burnt down in the Great Fire, and not rebuilt, its parish being annexed to that of St. Mildred, Poultry. The earliest date of an incumbent is 1252.

The patronage of the church was in the hands of Henry III., who presented to it one Roger de Messendene, April 21, 1252; then the Master and Brethren of St. Thomas de Acon; afterwards Henry VIII., who granted it to the Mercer’s Company, April 21, 1542.

Houseling people in 1548 were 220.

Chantries were founded here by Thomas de Cavendish, late citizen and mercer, at the Altar of St. Katherine, to which Roger de Elton was instituted chaplain, March 15, 1362-63; Agnes Fenne, who left by Will, dated March 28, 1541, £140 to maintain a priest for twenty years; Henry IV. granted a licence to William Marechalcap and others to found a Fraternity in honour of St. Katherine, February 19, 1399-1400; a further licence was granted by Henry VI., June 19, 1447, the endowment of which fetched £9 in 1548, when Robert Evans was Chaplain.

No monuments are recorded by Stow. In this church St. Thomas à Becket and St. Edmund were baptized. The parish had one gift-sermon, but no other gifts or legacies are recorded.

Thomas Horton (d. 1673), Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge, 1649, was a rector here.

24The Church of St. Olave, Jewry, stood on the west side, near the middle of Old Jewry, and was sometimes called St. Olave, Upwell. It was destroyed in the Great Fire and rebuilt in 1673. It was subsequently taken down. The tower, which alone was left, is now part of a dwelling-house. The earliest date of an incumbent is 1252.

The patronage of the church was in the hands of the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s, who granted it in 1171 to the Prior and Convent of Butley, Suffolk, when it became a vicarage. Henry VIII. seized it, and so it continues in the Crown.

Houseling people in 1548 were 198.

The open space, belonging to the ancient graveyard, abuts on Ironmonger Lane.

A chantry was founded here by John Brian, rector, who died in 1322, and a licence was granted by the King, August 20, 1323; Robert de Burton, chaplain, exchanged with William de Aynho, June 15, 1327. In 1548 the endowment fetched £13 : 1 : 4.

Robert Large, Mayor in 1440, and donor of £200 to the church, was buried here. Among the later monuments is one in memory of Sir Nathaniel Herne, Governor of the East India Company; he died 1679.