Project Gutenberg's Mediæval London, v. 1-2, by Walter (Sir) Besant Produced by Chris Curnow, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The Survey of London

MEDIÆVAL

LONDON

ECCLESIASTICAL

MEDIÆVAL

LONDON

VOL. II

ECCLESIASTICAL

BY

SIR WALTER BESANT

LONDON

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK

1906

v

CONTENTS

| PART I | ||

| THE GOVERNMENT OF LONDON | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| 1. | The Records | 3 |

| 2. | The Charter of Henry the Second | 8 |

| 3. | The Commune | 11 |

| 4. | The Wards | 24 |

| 5. | The Factions of the City | 35 |

| 6. | The Century of Uncertain Steps | 66 |

| 7. | After the Commune | 72 |

| 8. | The City Companies | 108 |

| PART II | ||

| ECCLESIASTICAL LONDON | ||

| 1. | The Religious Life | 127 |

| 2. | Church Furniture | 159 |

| 3. | The Calendar of the Year | 164 |

| 4. | Hermits and Anchorites | 170 |

| 5. | Pilgrimage | 179 |

| 6. | Ordeal | 191 |

| 7. | Sanctuary | 201 |

| 8. | Miracle and Mystery Plays | 213 |

| 9. | Superstitions, etc. | 218 |

| 10. | Order of Burial | 223 |

| PART III | ||

| RELIGIOUS HOUSES | ||

| 1. | General | 227 |

| 2. | St. Martin’s-le-Grand | 234 |

| 3. | The Priory of the Holy Trinity, or Christ Church Priory | 241 |

| 4. | The Charter House | 245 vi |

| 5. | Elsyng Spital | 248 |

| 6. | St. Bartholomew | 250 |

| 7. | St. Thomas of Acon | 263 |

| 8. | St. Anthony’s | 268 |

| 9. | The Priory of St. John of Jerusalem | 270 |

| 10. | The Clerkenwell Nunnery | 284 |

| 11. | St. John the Baptist, or Holiwell Nunnery | 286 |

| 12. | Bermondsey Abbey | 288 |

| 13. | St. Mary Overies | 297 |

| 14. | St. Thomas’s Hospital | 309 |

| 15. | St. Giles-in-the-Fields | 311 |

| 16. | St. Helen’s | 313 |

| 17. | St. Mary Spital | 322 |

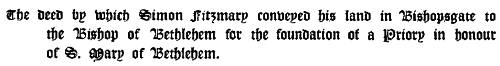

| 18. | St. Mary of Bethlehem | 325 |

| 19. | The Clares | 329 |

| 20. | St. Katherine’s by the Tower | 334 |

| 21. | Crutched Friars | 342 |

| 22. | Austin Friars | 344 |

| 23. | Grey Friars | 348 |

| 24. | The Dominicans | 354 |

| 25. | Whitefriars | 360 |

| 26. | St. Mary of Graces | 363 |

| 27. | The Smaller Foundations | 365 |

| 28. | Fraternities | 382 |

| 29. | Hospitals | 385 |

| APPENDICES | ||

| 1. | List of Wards of London | 391 |

| 2. | List of Aldermen | 393 |

| 3. | Alphabetical List of Aldermen whose Names are affixed to Deeds in the Thirteenth Century | 395 |

| 4. | List of Parishes | 397 |

| 5. | Patronage of City Churches | 400 |

| 6. | Festivals | 401 |

| 7. | An Anchorite’s Cell | 404 |

| 8. | The Monastic Houses | 406 |

| 9. | A Dominican House | 407 |

| 10. | The Papey | 411 |

| 11. | Charitable Endowment | 413 |

| 12. | Fraternities | 420 |

| INDEX | 423 | |

vii

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | ||

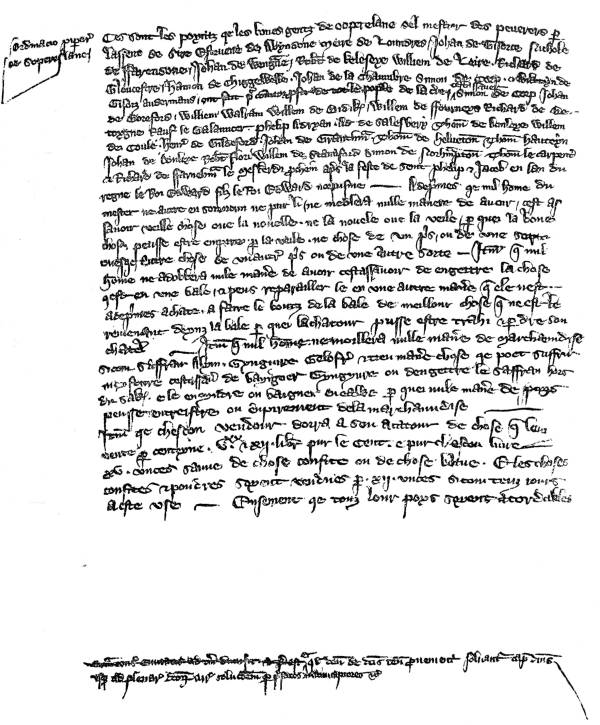

| Extract from Letter-Book E, dated 1316, relating to the Grocers’ Company | 5 | |

| Obverse and Original Reverse of the Seal of the City of London, showing Figure of St. Thomas à Becket | 13 | |

| Old Mayoralty Seal, Thirteenth Century | 15 | |

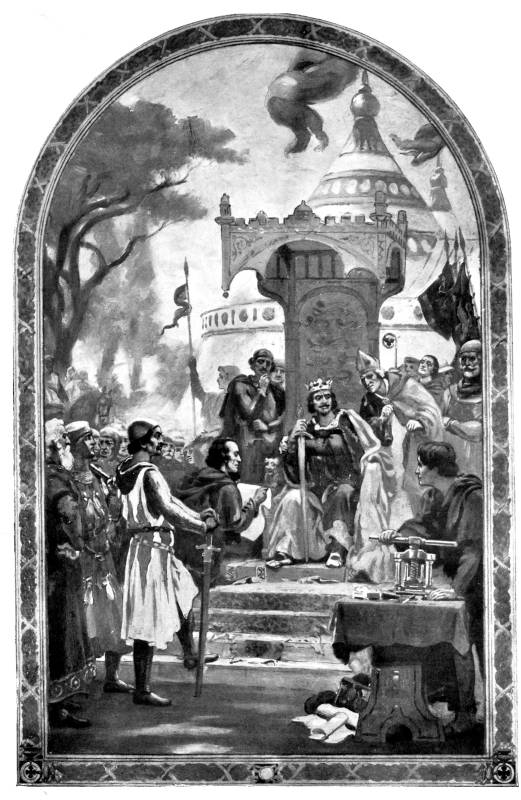

| King John signing Magna Charta | Facing 20 | |

| Aldgate House, Bethnal Green | 25 | |

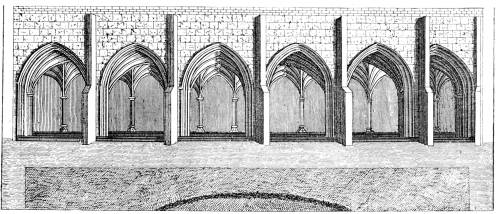

| Parts of the South and West Walls of a Convent | 30 | |

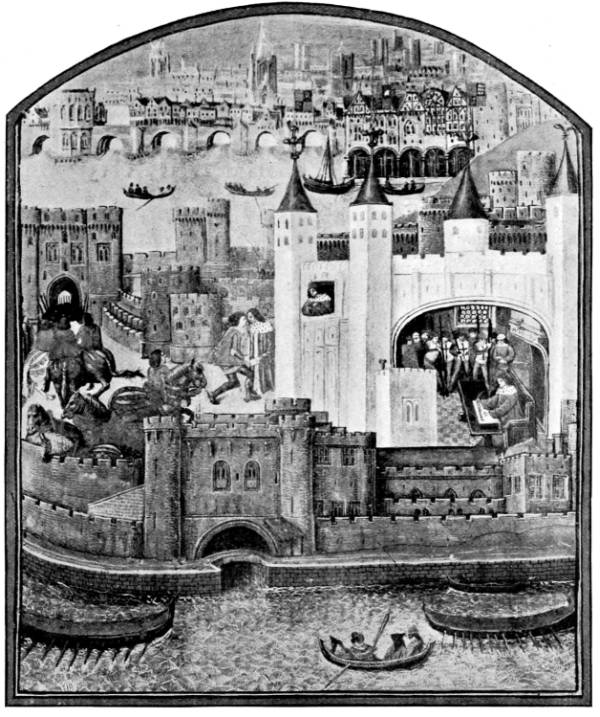

| The Tower of London about 1480 | 39 | |

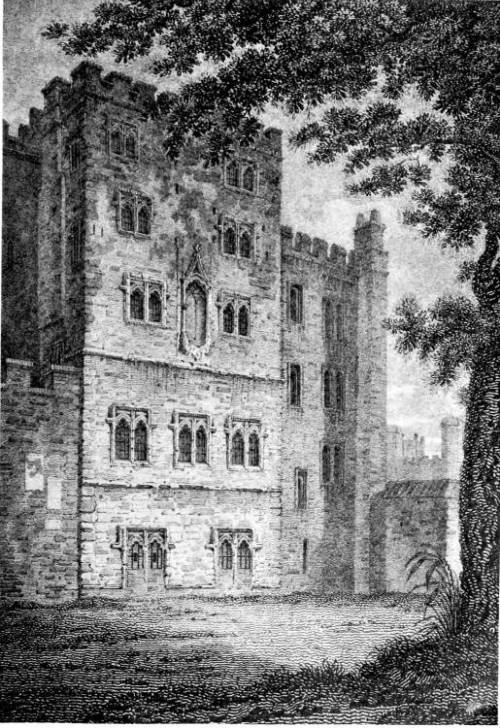

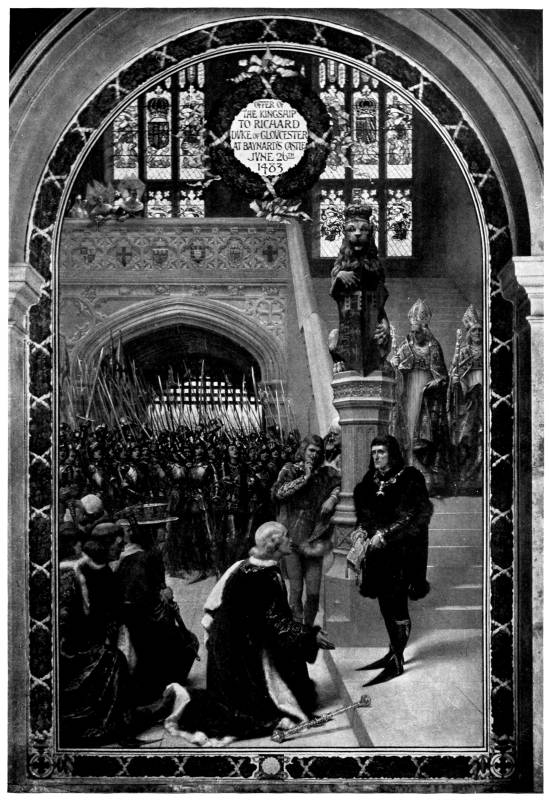

| The Crown offered to Richard III. at Baynard’s Castle | Facing 56 | |

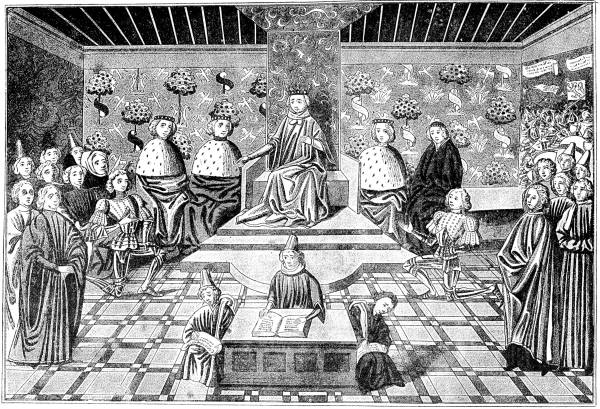

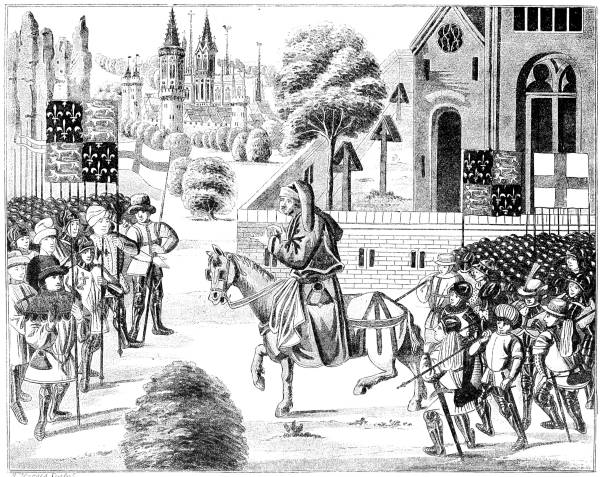

| King Richard holding a Council of Nobles and Prelates | 61 | |

| Henry of Bolingbroke challenges the Crown | 62 | |

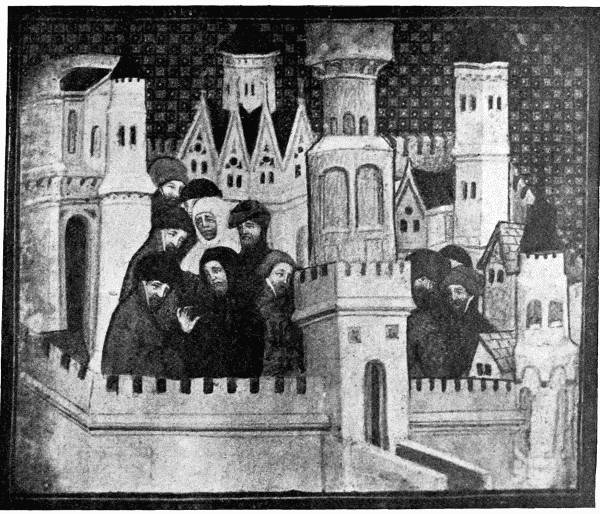

| Richard II. consulting with his Friends in Conway Castle | 63 | |

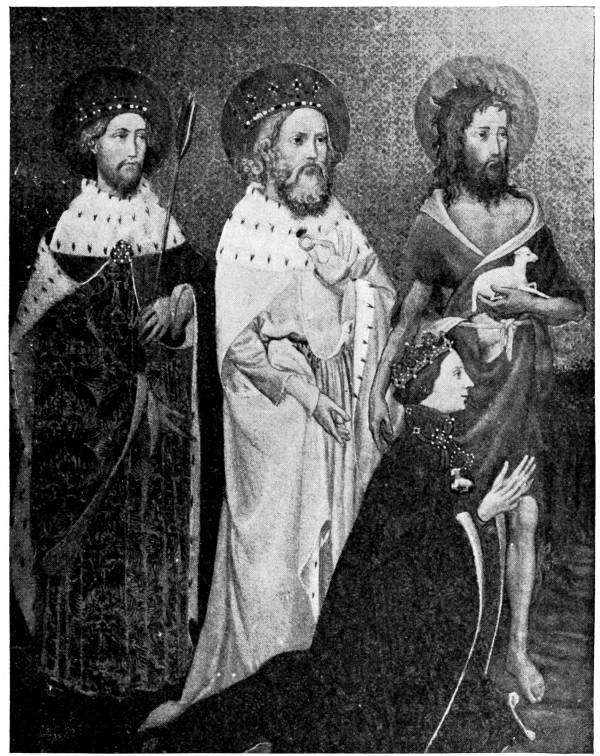

| Richard II. and his Patron Saints | 69 | |

| Whittington and his Cat | 73 | |

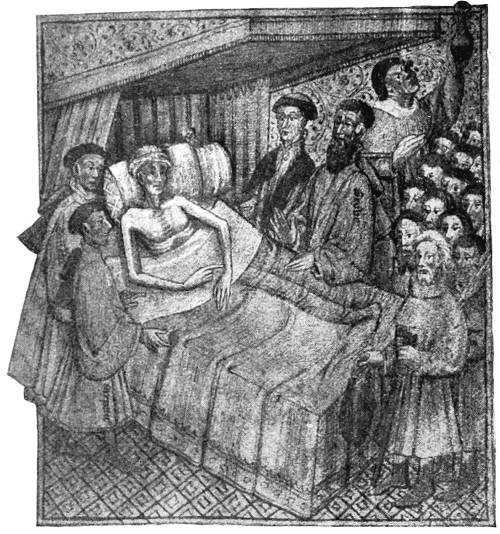

| Death of Whittington | 74 | |

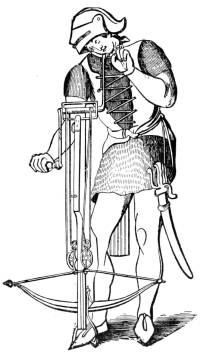

| Crossbowman | 77 | |

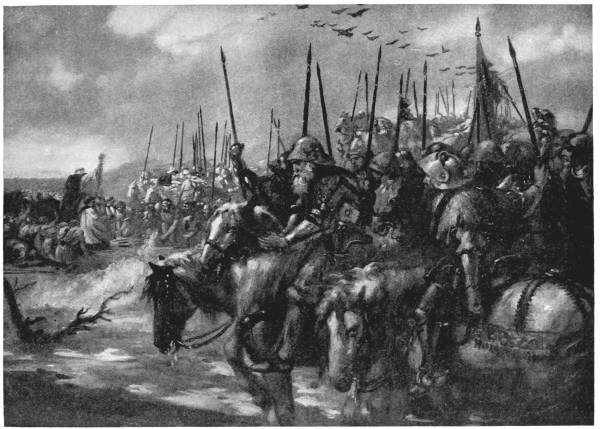

| The Morning of Agincourt | 81 | |

| Facsimile of Heading of Account, 1575-1576, showing Cooper at Work | 85 | |

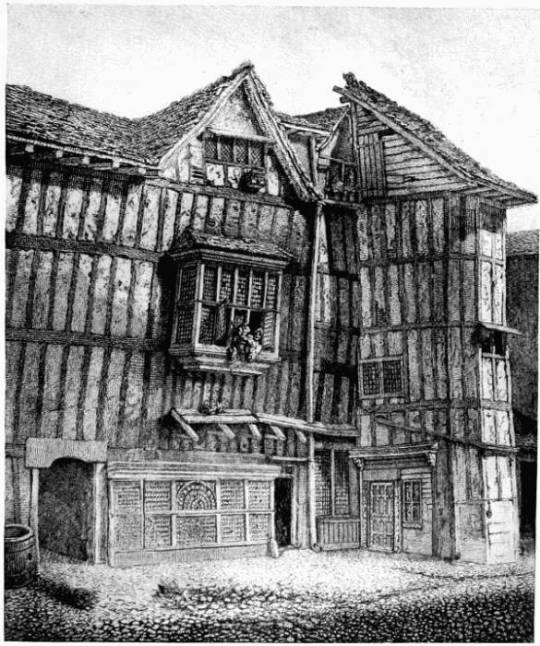

| South-East View of the Old House lately standing in Sweedon’s Passage, Grub Street | 91 | |

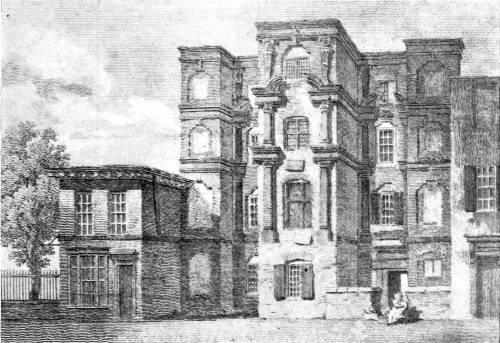

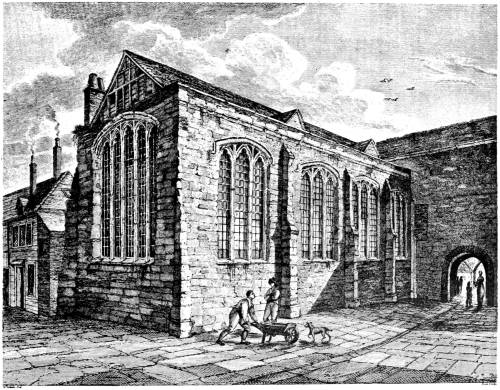

| South-West View of Gerrard’s Hall | Facing 100 | |

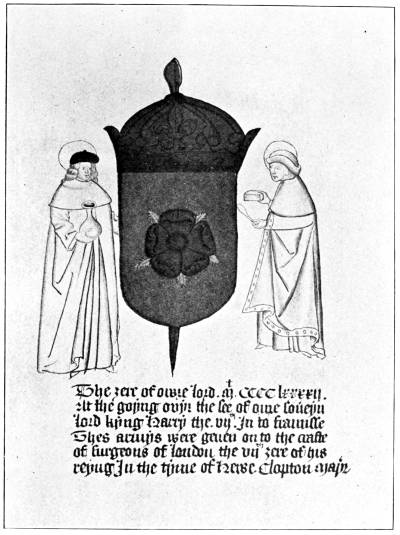

| Facsimile of Surgeons’ Arms, 1492, with St. Cosmo and St. Damian supporting | 101 | |

| Interior of the Guildhall | 103 | |

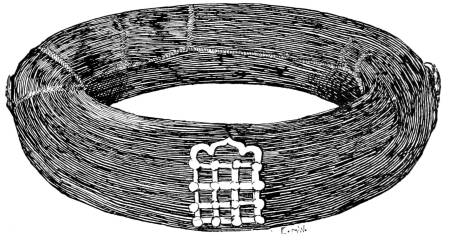

| A Tally for 6s. 8d. issued by Edward I.’s Treasurer to the Sheriff of Lincolnshire | 105 | |

| Election Garland given by Robert and Cicely Chamberlayn, 1463 | 105 | |

| A Bagpipe-Player | 110 | |

| Illustration from Zeller’s La France Anglaise et Charles VII. | 111 | |

| The Seal of the Vintners’ Company, 1437 | 112 | |

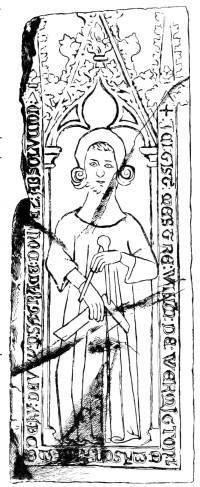

| Tombstone of William Warrington, Master Mason, at Croyland Abbey, 1427 | 113 | |

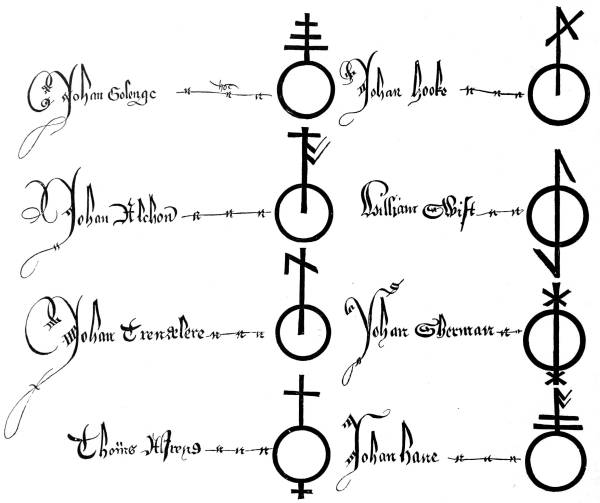

| Coopers’ Marks, A.D. 1420 | 114 | |

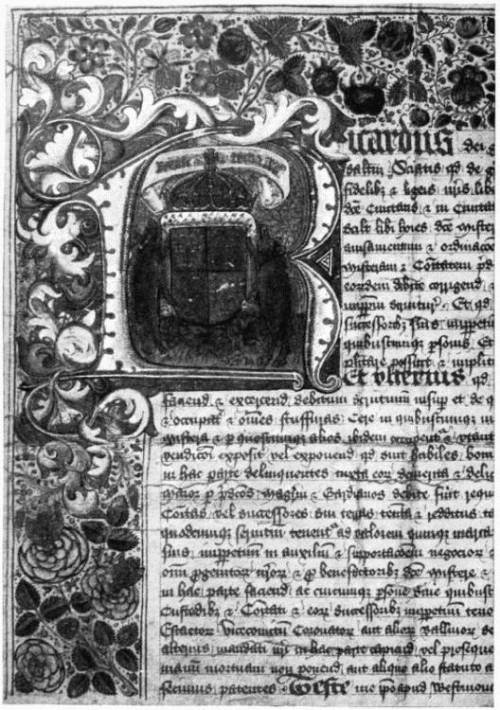

| Part of Facsimile of the Original Charter granted by King Richard III. to the Worshipful Company of Wax Chandlers of the City of London (16th February, 1 Richard III.) | 116 | |

| Liverymen of London | 117 | |

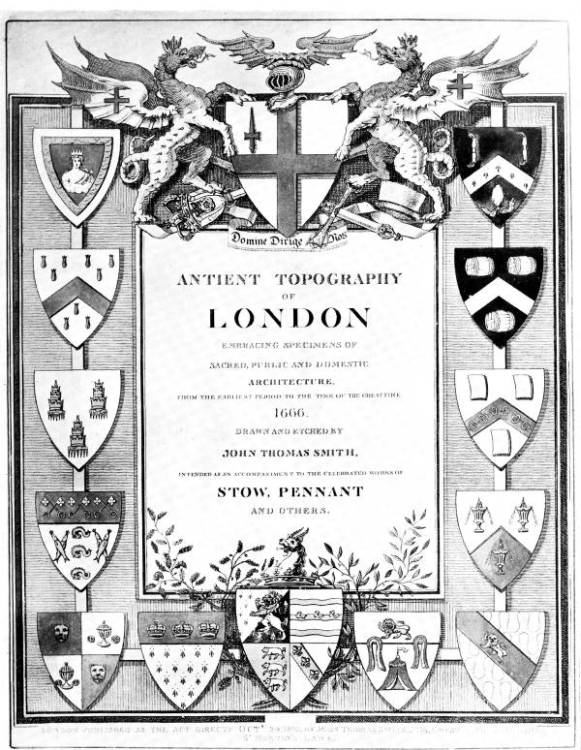

| Frontispiece to the Grangerised Edition of Brayley’s London and Middlesex | Facing 118 | |

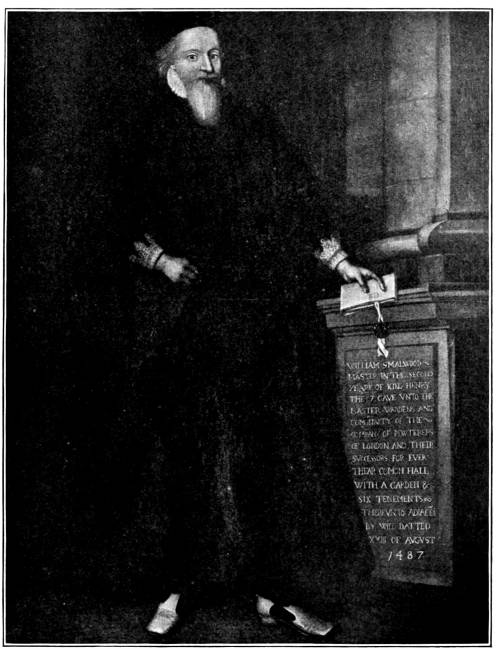

| William Smallwood, Master of the Pewterers’ Company | 121 | |

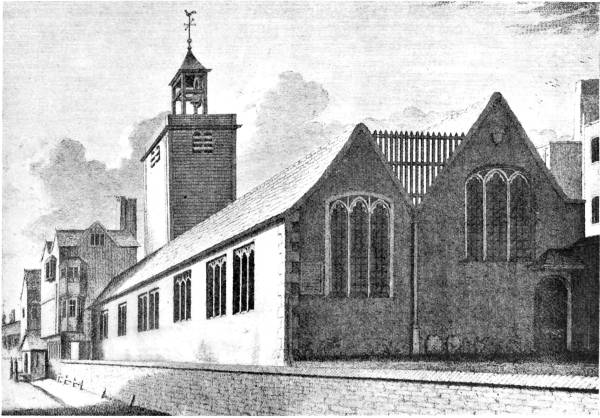

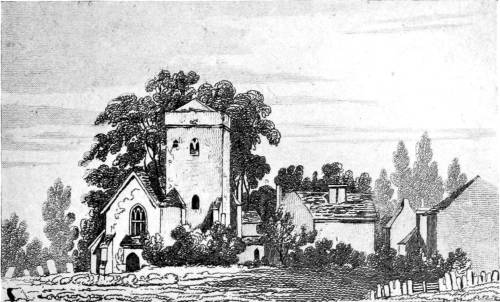

| St. Ethelburga’s Church, Bishopsgate Street | 129 | |

| The Prioress | 131 | |

| The Monk and his Greyhounds | 131 | |

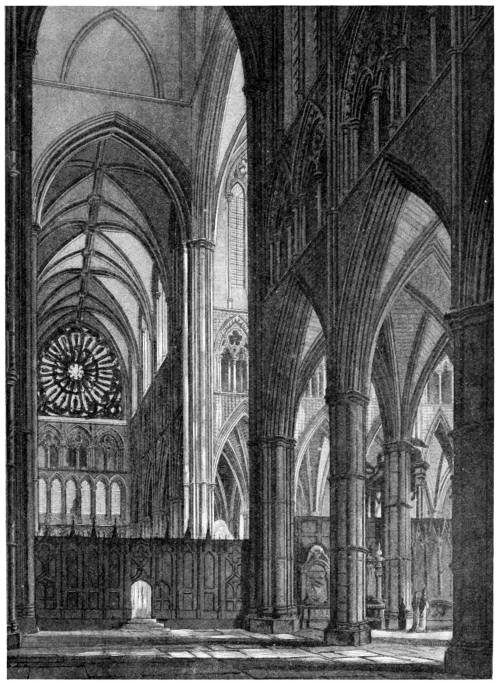

| Chantry Chapel of Henry V. in Westminster Abbey | 133viii | |

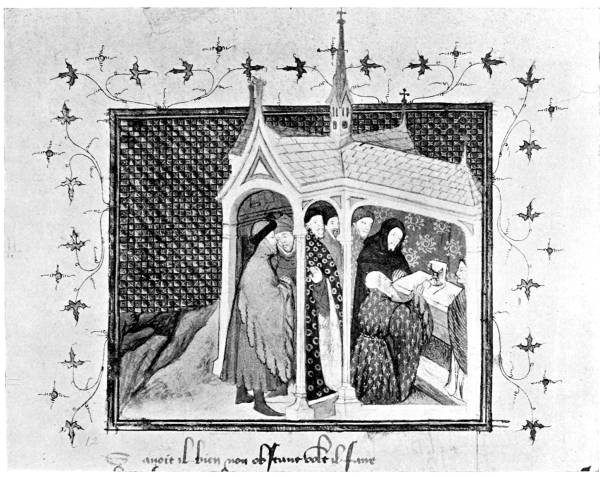

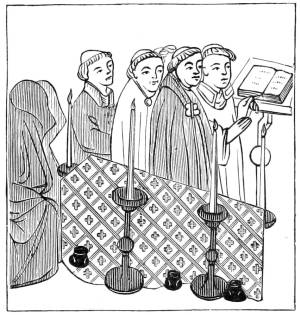

| Earl of Northumberland receiving Mass | 135 | |

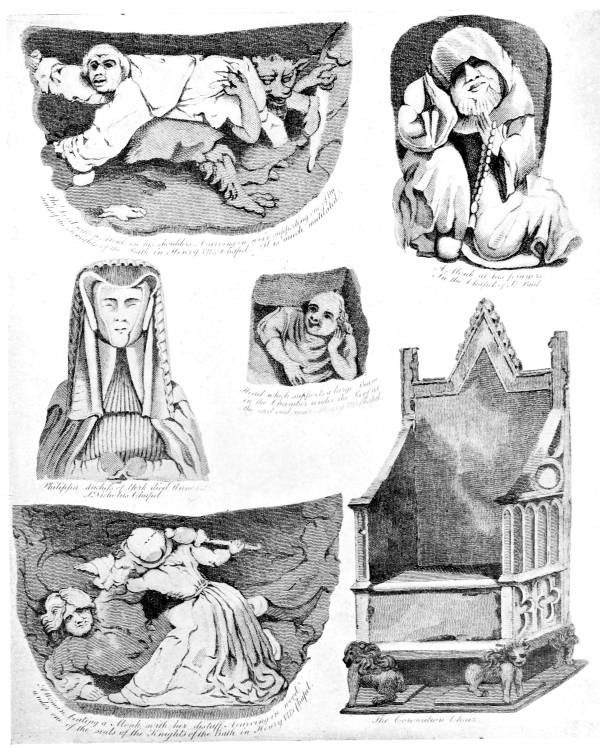

| Interesting Antiquities in Westminster Abbey | Facing 138 | |

| Savoy Chapel and Palace | 141 | |

| The Lollard’s Tower, Lambeth Palace | 149 | |

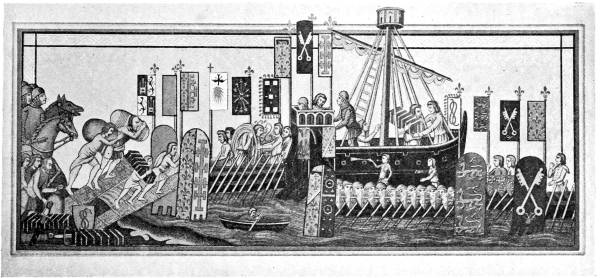

| Knights of the Holy Ghost embarking for the Crusades | 151 | |

| A Priest called John Ball stirs up great Commotion in England | 155 | |

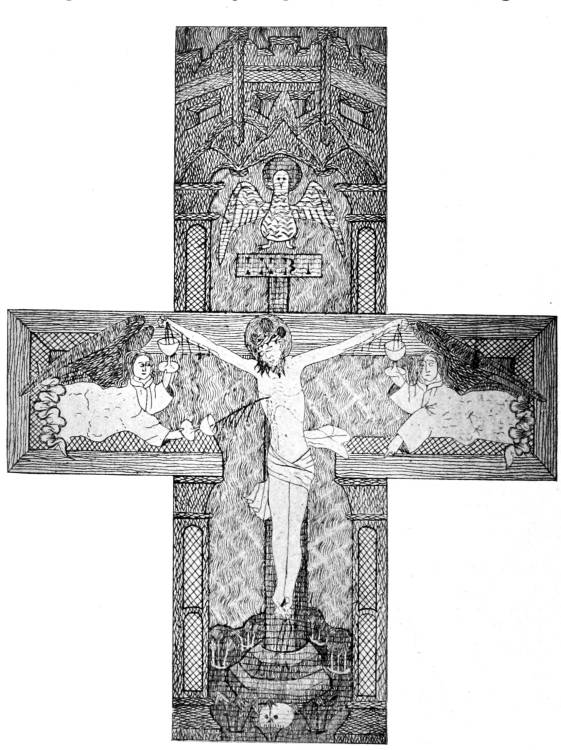

| Embroidery of the Fourteenth Century, supposed to be part of a Frontal or Antependium | 160 | |

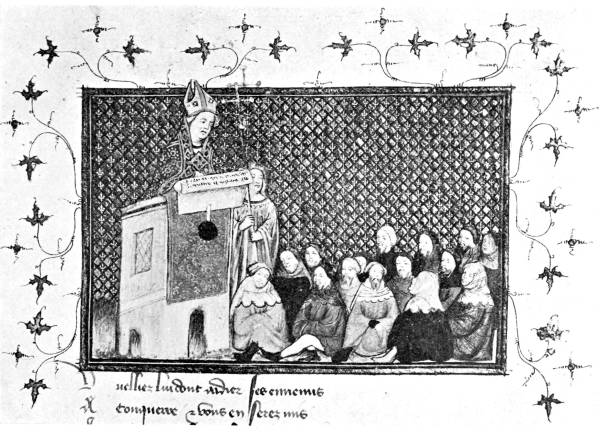

| Archbishop of Canterbury preaching on behalf of Henry, Duke of Lancaster | 161 | |

| Queen Margaret, Wife of Henry VI., at Prayers | 168 | |

| All Hallows, London Wall | 175 | |

| Wilsdon, Middlesex | 181 | |

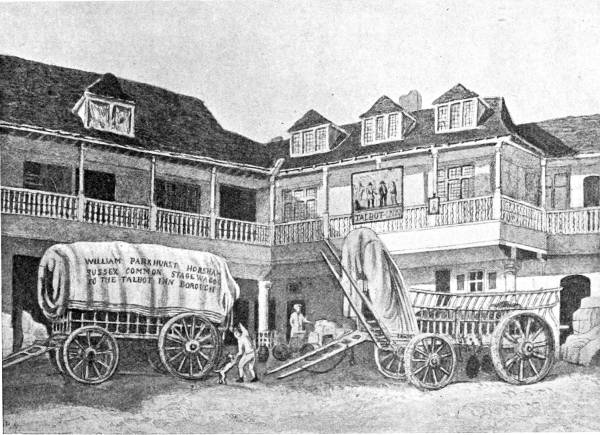

| The Tabard Inn, Borough | 187 | |

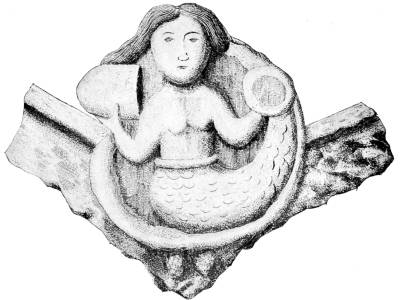

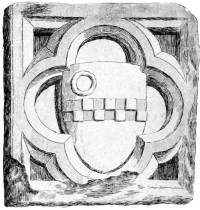

| Boss from the Ruins of the East Cloister of St. Bartholomew’s Priory | 195 | |

| Sanctuary Knocker, Durham Cathedral | 202 | |

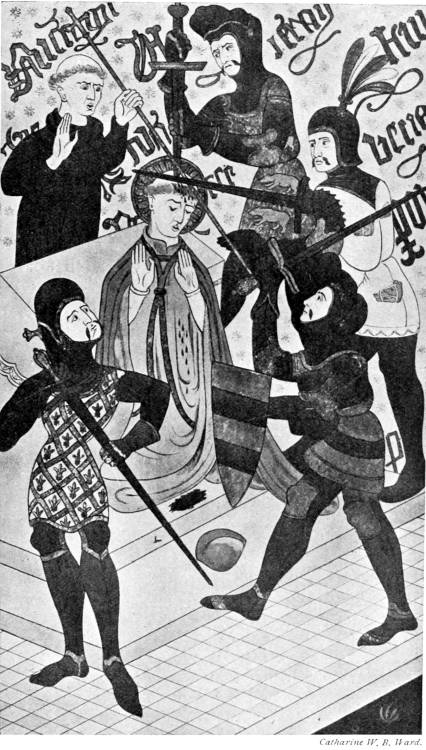

| The Martyrdom of St. Thomas | 203 | |

| Brasses in St. Bartholomew the Less, Smithfield | 207 | |

| The Sanctuary Church at Westminster | 209 | |

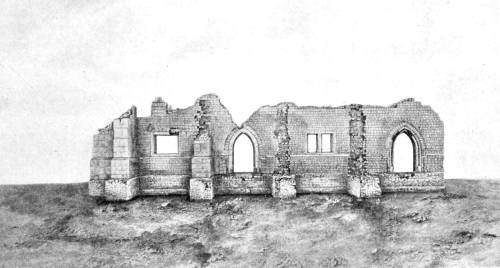

| North-West View of the Ruins of the Bishop of Winchester’s Palace, Southwark | 215 | |

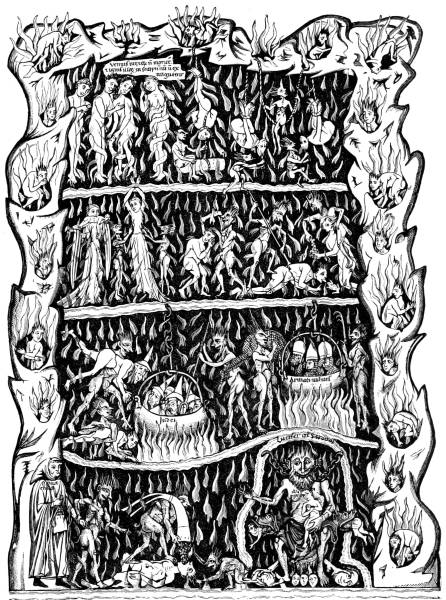

| Torments of Hell | 219 | |

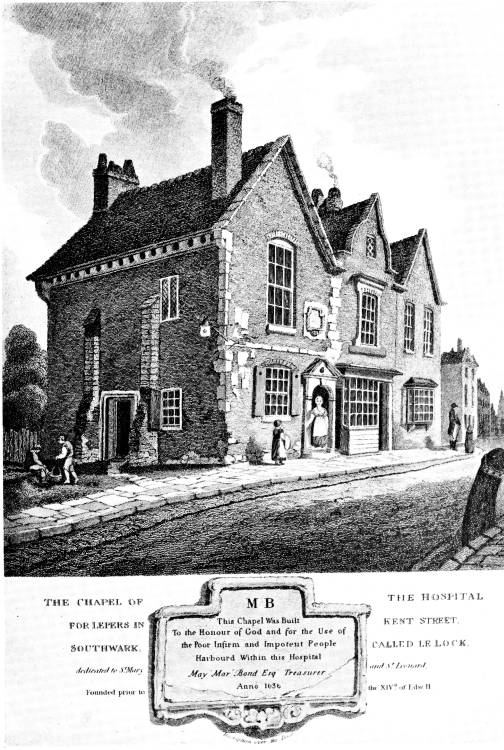

| The Chapel of the Hospital for Lepers in Kent Street, Southwark, called Le Lock | Facing 220 | |

| Funeral Service | 223 | |

| North View of the Oratory of the Ancient Inn situated in Tooley Street, Southwark, and formerly belonging to the Priors of Lewes in Sussex | 229 | |

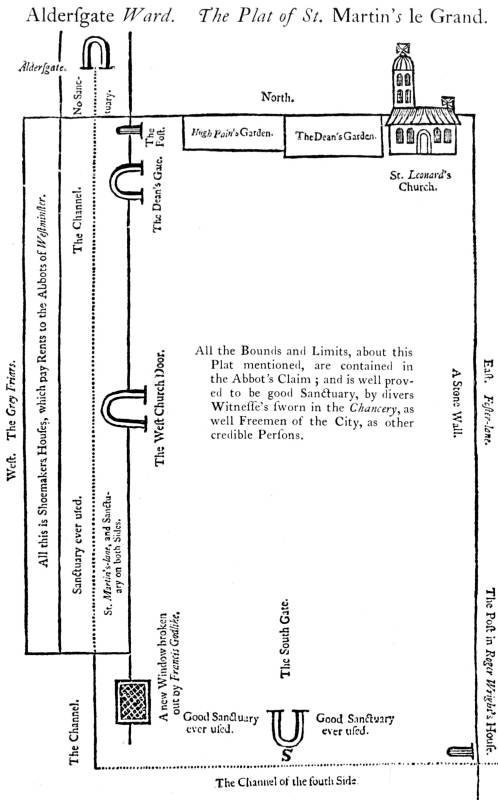

| The Sanctuary of St. Martin’s-le-Grand | 235 | |

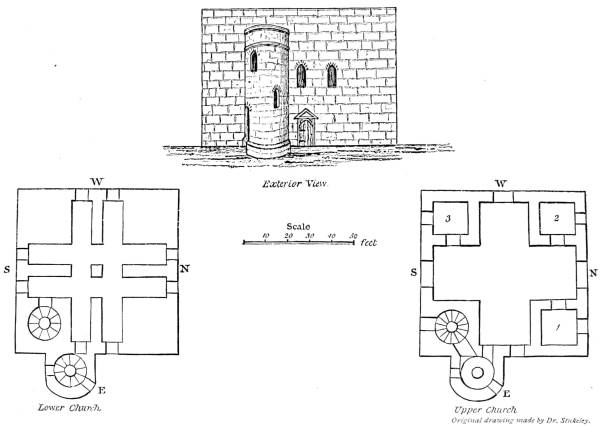

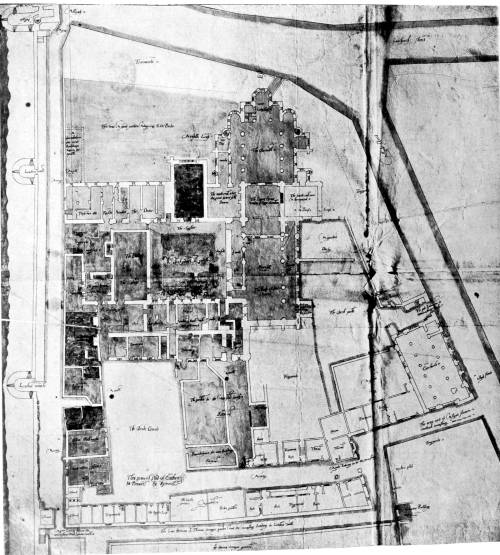

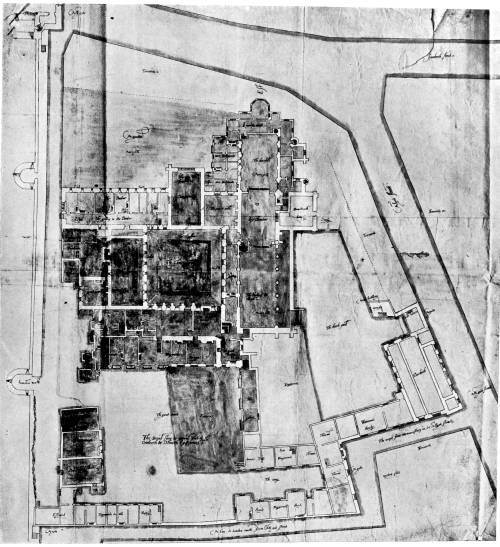

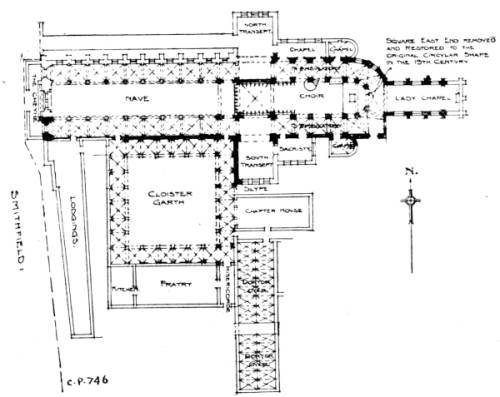

| Plan of Holy Trinity Priory (Ground Floor Story) |  |

Between 244 and245 |

| Plan of Holy Trinity Priory (Second Floor Story) | ||

| The Charter House | 246 | |

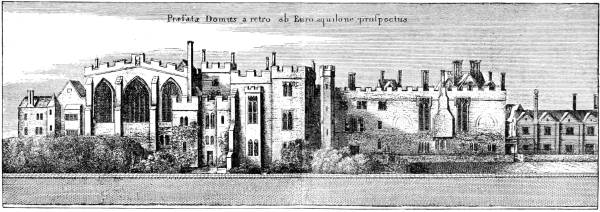

| Conjectural Restoration of the Buildings of the Priory Church of St. Bartholomew the Great as existing in Prior Bolton’s time (about A.D. 1530) | 251 | |

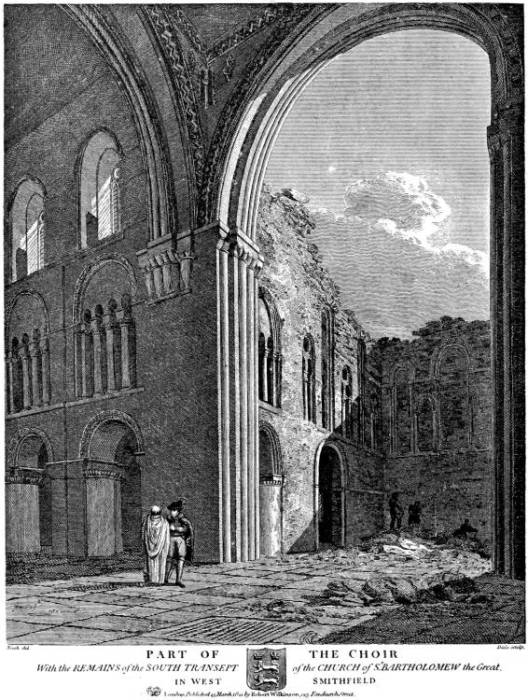

| Part of the Choir, with the Remains of the South Transept, of the Church of St. Bartholomew the Great | 252 | |

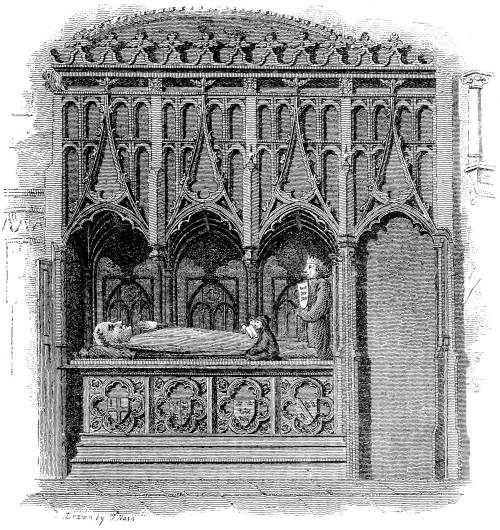

| Tomb of Prior Rahere | 253 | |

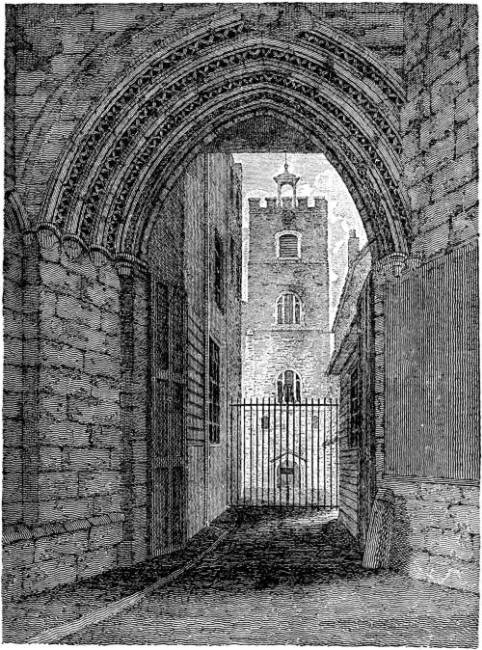

| The Gate of St. Bartholomew’s Priory | 255 | |

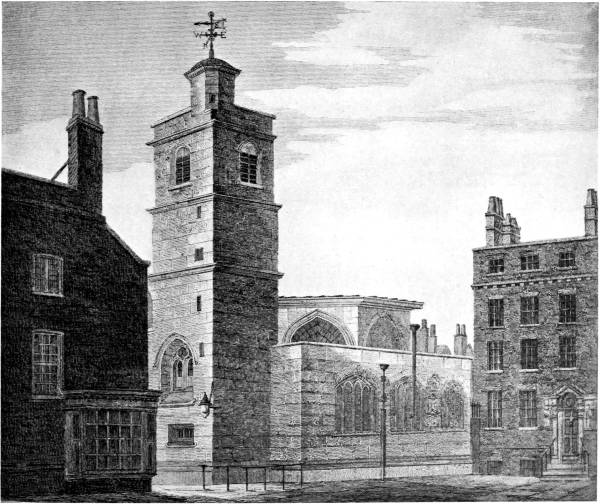

| St. Bartholomew the Less | 257 | |

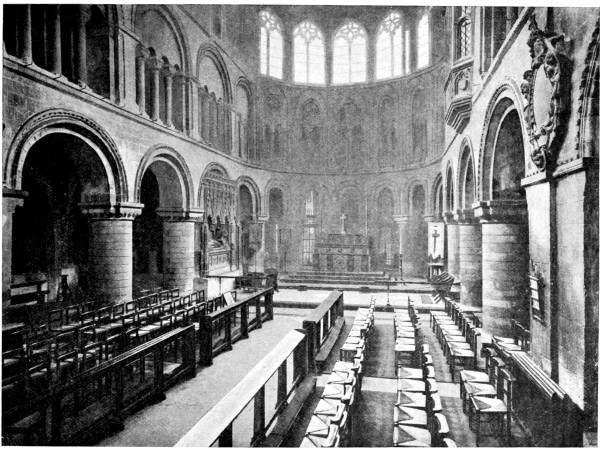

| Interior of St. Bartholomew the Great | 259 | |

| Eastern Cloister of St. Bartholomew’s Priory | 261 | |

| Seal of the Hospital of St. Thomas of Acon | 263 | |

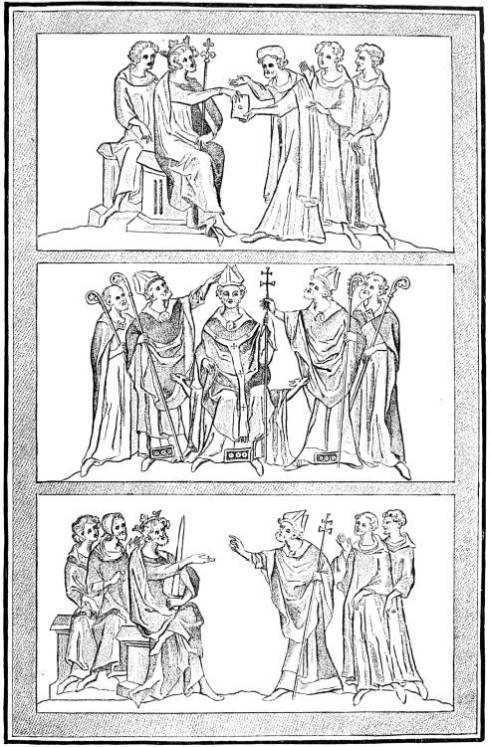

| Becket receiving a letter from Henry II. constituting him Chancellor. Consecration of Becket to the See of Canterbury. Becket approaching the King with Disapprobation | 265 | |

| The Priory of St. John of Jerusalem, London | 271 | |

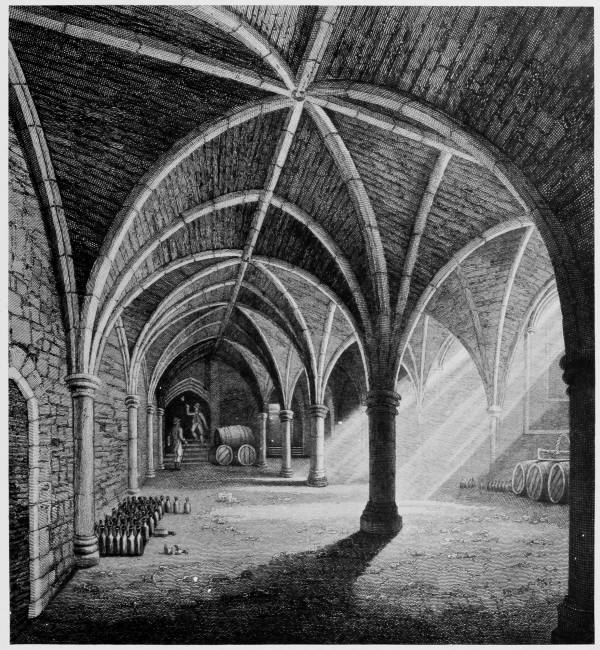

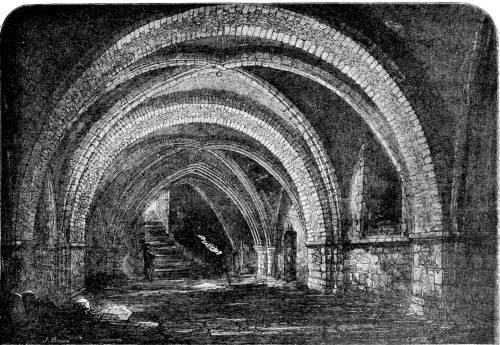

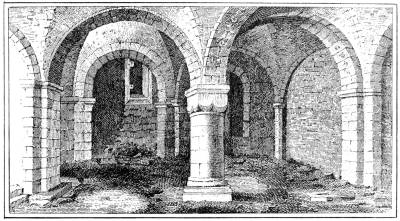

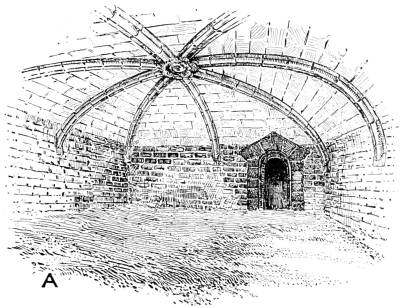

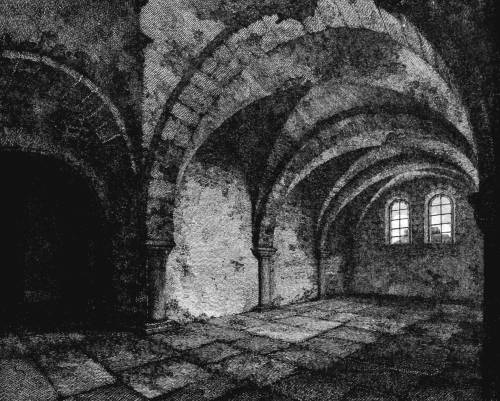

| Crypt of St. John’s Church, Clerkenwell | 273 | |

| “The Templars”: an Ancient House at Hackney | 275 | |

| Knight Templar | 276 | |

| Knight Templar: Temple Church | 276 | |

| An Effigy at the Temple Church, erroneously described as that of Sir Geoffrey de Mandeville | 277 | |

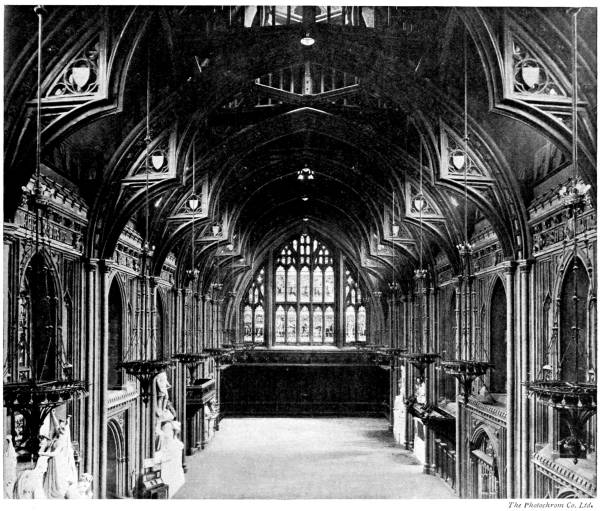

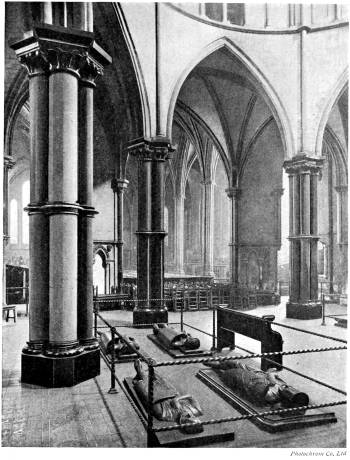

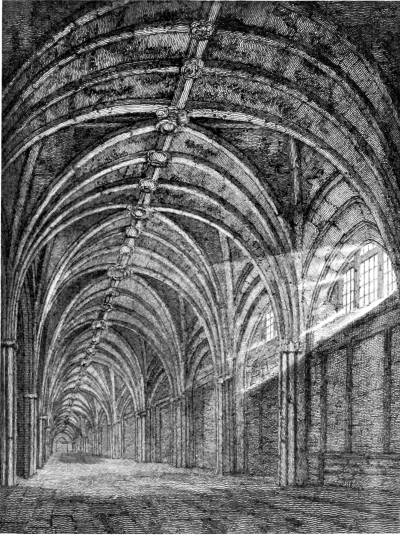

| Interior of the Temple Church | 279ix | |

| Ancient Cloisters in Clerkenwell | 285 | |

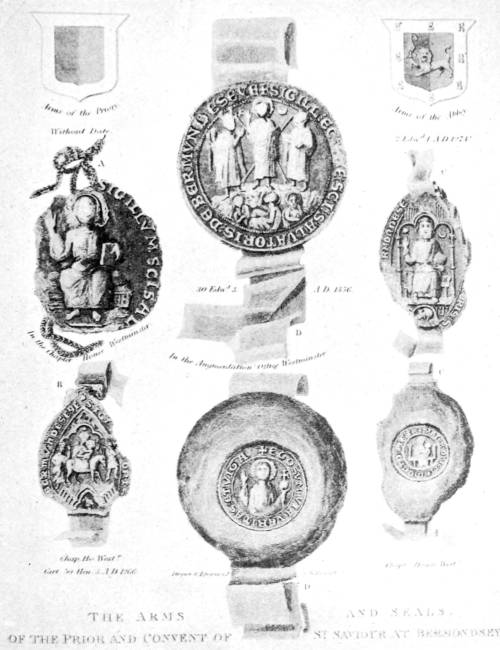

| The Arms and Seals of the Prior and Convent of St. Saviour at Bermondsey | 289 | |

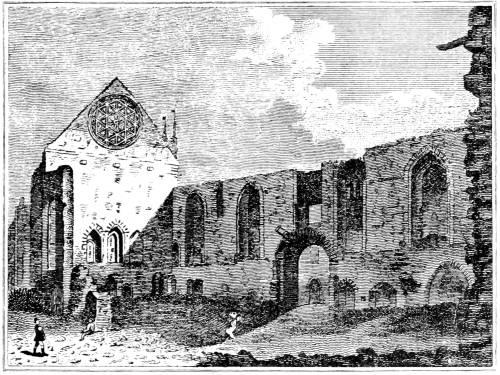

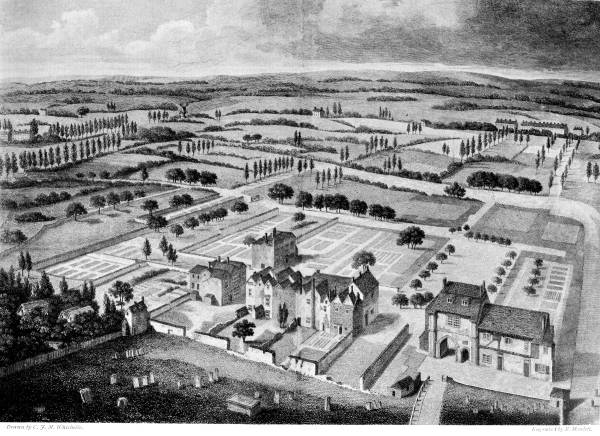

| Bermondsey Abbey | 293 | |

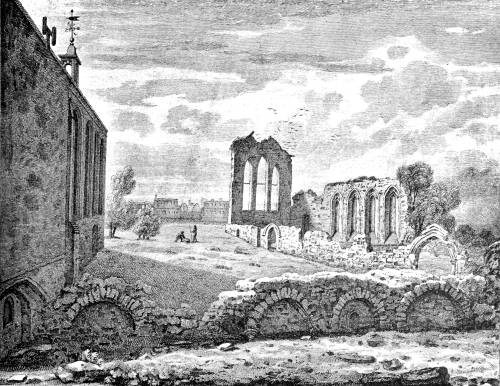

| A General View of the Remains of Bermondsey Abbey, Surrey | Facing 294 | |

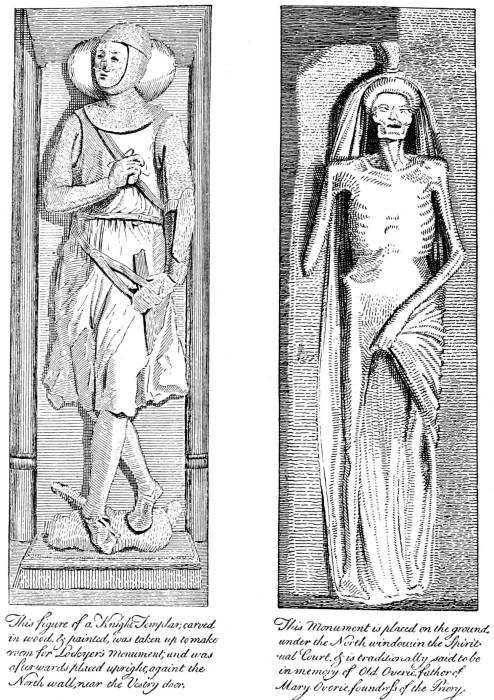

| Figure of a Knight Templar |  |

298 |

| Traditional Figure of Old Overie | ||

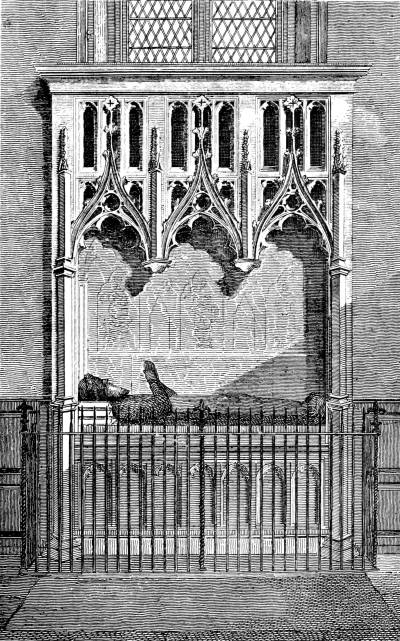

| Gower’s Monument, St. Mary Overies | 299 | |

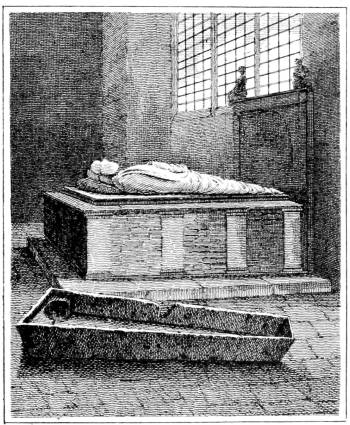

| Bishop Andrewes’ Tomb, St. Mary Overies | 301 | |

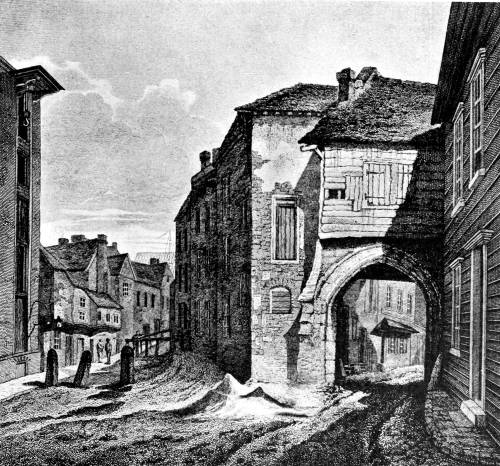

| Gateway of St. Mary’s Priory, Southwark | 303 | |

| Ancient Crypt, Southwark | 305 | |

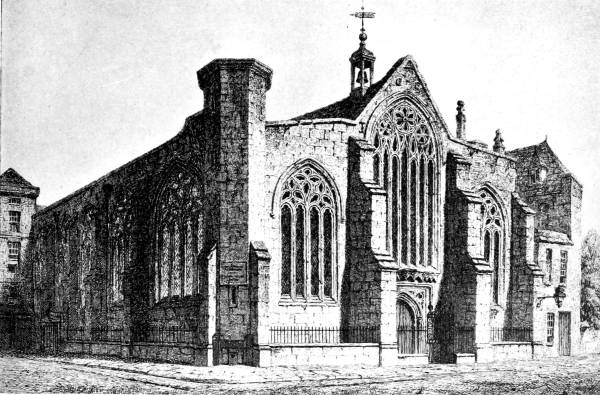

| North-East View of St. Saviour’s Church | 307 | |

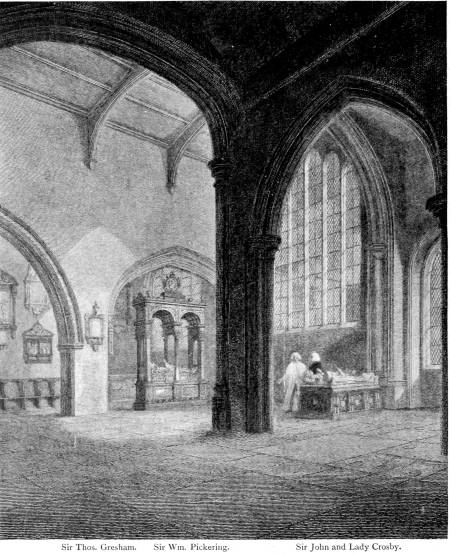

| South-West View of the Interior of the Church of St. Helen, Bishopsgate Street | 314 | |

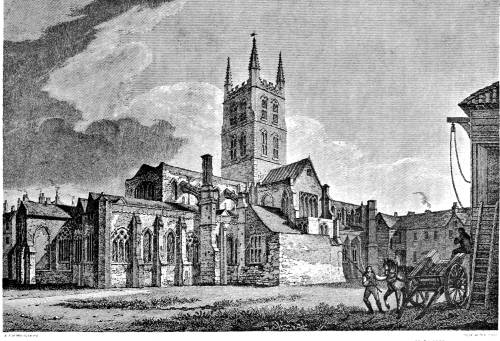

| South-East View of the Nunnery of St. Helen, Bishopsgate Street | 315 | |

| The Crypt of the Nunnery of St. Helen, in Bishopsgate Street | 317 | |

| Seals of St. Helen’s Nunnery | 319 | |

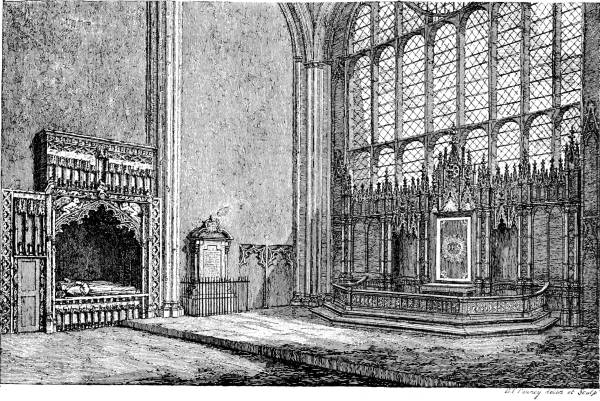

| The Gothic Altar-piece in the Collegiate Church of St. Katherine, with the Monuments of the Duke of Exeter and of the Hon. G. Montague | 335 | |

| The Church of Austin Friars | 345 | |

| Arms of Sir R. Whittington, Grey Friars, now Christ’s Hospital | 348 | |

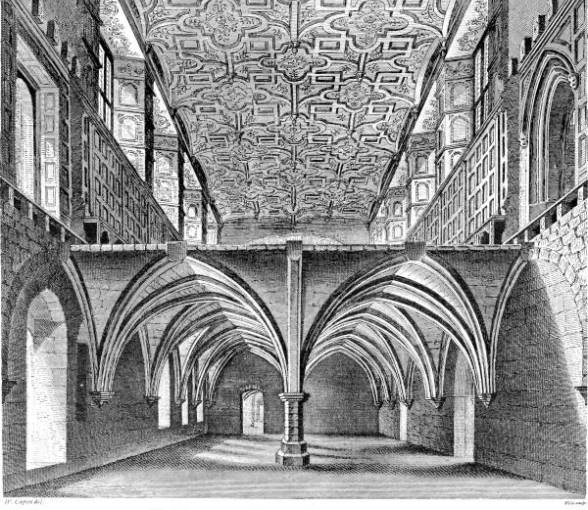

| Christ’s Hospital, from the Cloisters | 349 | |

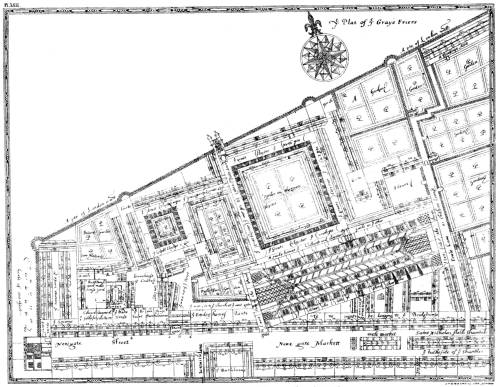

| “Ye Plat of Ye Graye Friers,” A.D. 1617 | 351 | |

| Blackfriars’ Priory | 355 | |

| A Column of the Hall of Blackfriars’ Priory | 357 | |

| Crypt of Old Whitefriars’ Priory | 361 | |

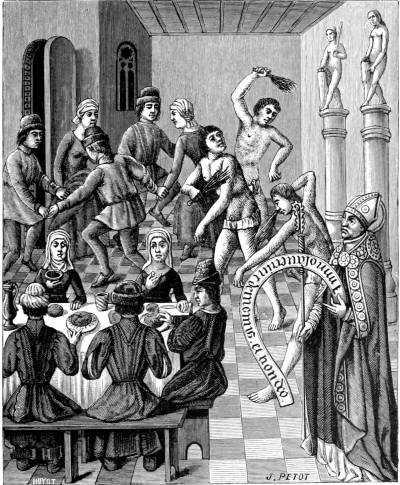

| Flagellants | 367 | |

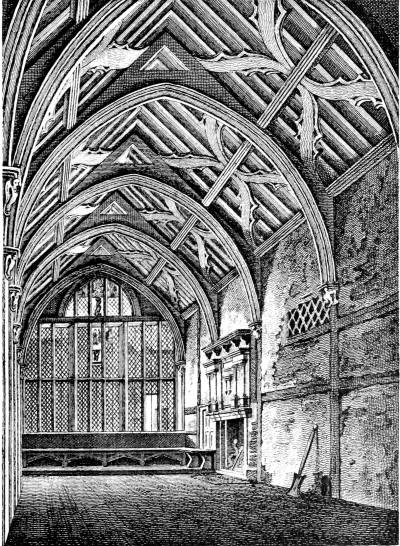

| Interior of Old Lambe’s Chapel, Monkwell Street | 369 | |

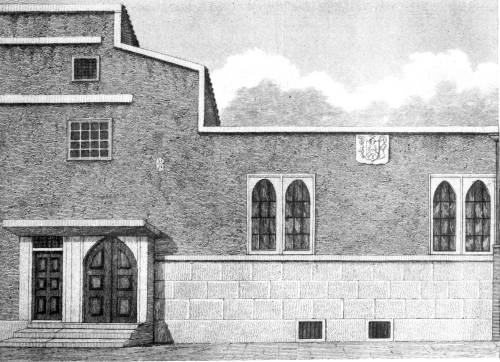

| Exterior of the South Side of Old Lambe’s Chapel | 371 | |

| North-East View of the Chapel of the Holy Trinity, Leadenhall, in the Parish of St. Peter-upon-Cornhill, London | 375 | |

| Hall of the Brotherhood of the Holy Trinity | 383 | |

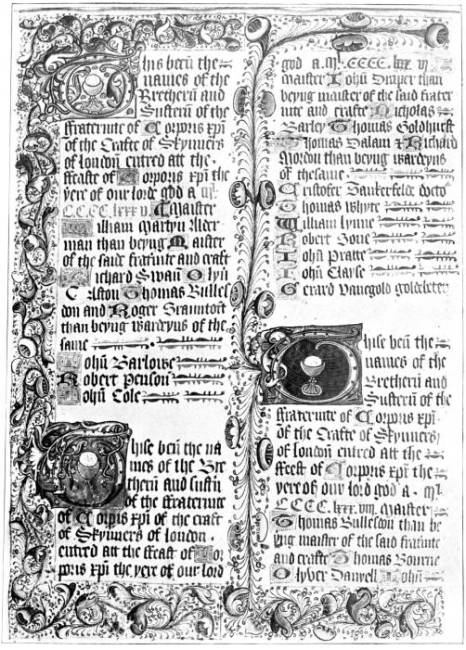

| Page of the Roll containing the names of the “Brethren and Sisters” of the Guild of Fraternity of Corpus Christi, 1485, 1486, 1488 | Facing 384 | |

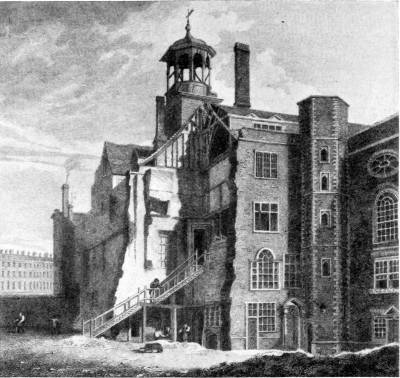

| North-West View of the Chapel and Part of the Great Staircase leading to the Hall of Bridewell Hospital, London | 386 | |

PART I

THE GOVERNMENT OF LONDON

3

CHAPTER I

THE RECORDS

Before entering upon the government of London under the Plantagenet Kings, let us first ask what are the documents in which we shall find information at first hand.

No city in the world possesses a collection of archives so ancient and so complete as the collection at the Guildhall. Riley, in his Introduction to the Liber Albus, begins his list of those who have consulted the archives with John Stow. Surely, however, the compiler of the Liber Albus itself, John Carpenter, also consulted archives even in his day valuable and ancient. Strype, in the preparation of his Edition of Stow, also consulted the City archives:—

“Again,” he says, “another Thing, that Labour and Diligence hath been bestowed in, relates to the Laws, Customs and Usages of the City. Wherein the Liberties and Privileges, as well as the Duties of the Citizens, are contained. And therefore ought to be known by them, and in that regard necessary to be set down, as accurately and largely as might be; being Things so material for them to be advised of. This was laudably begun by A. M. in the last Edition: but very much improved and enlarged in this. And to enable me the better in the doing the same, it was not only necessary to gather up, and present the many and most important Acts of Parliament and Common Council, relating to the City and its Affairs; but also to have recourse to the authentick Books and Records belonging to the Chamber of London: Where many ancient and curious Matters of this nature might be found. But this seemed to be somewhat difficult to be obtained. Yet by the Help of some friends of Quality and good Account, and making the Court of Aldermen acquainted with my Design, and requesting their Leave and Licence, I obtained an Order from them to Mr. Ashhurst, then Town Clerk, to give me Access to some of their Books, that might be most to my Purpose, and their Allowance to transcribe what I thought convenient out of them: but withal I was enjoined by the Court to leave in Mr. Town Clerk’s hands all my Notes that I should so collect thence, to be reviewed and examined; lest some things published from them might seem prejudicial some way or other to the City, or be judged not so convenient to be known; or lest any Mistakes might4 be made by me in transcribing. Which (as was fit), I readily complied with. Many Remarks I took out thence, respecting both the ancient State of the City, and also of the Courts, the Customs, the Magistrates, the Officers, &c. The Chief Books I conversed with, were those two famous ancient Volumes, the one called Liber Horne, from the Writer, the other called Liber Albus, i.e. the White Book. Both so often made use of and cited by Mr. Stow. This last mentioned Book was composed in Latin, An. 1419. 7. H. 5. mense Novembris. And what it contains is known by what is writ in one of the First Pages, viz. Continens tam laudabiles Observantias, non scriptas, in dict. Civitate fieri solitas, quam notabilia memoranda, &c., sparsim et inordinate scripta. That is, ‘Containing as well laudable Customs, not written, wont to be observed in the said City, as other notable things worthy remembering, here and there scatteringly, not in any Order written.’ The Compiler of this White Book was one Carpenter: whose Name fairly and largely writ fronts the first page. Who I suppose may be that J. Carpenter, sometime Town Clark in the Reign of Henry V., mentioned by Stow in his Survey among the worthy Benefactors of the City: and whose Gifts are there set down. In this Volume are inserted Memorials of the Maiors, Sheriffs, Recorders, Chamberlains, and the other chief officers of the City: likewise all the Charters granted by the several Kings of England from William the Conqueror: and the Confirmations thereof. There is also a Tract of the Manner and Order, ‘How Barones & Universitas Civitat. London, &c. That is, the Barons (i.e. the Freemen) and Commonality of the City of London, ought to behave and carry themselves towards the King and his Justitiaries Itinerants in the Time it pleaseth the King to hold Pleas of the Crown at the Tower of London: Together with many other Matters and Subjects, contained in this Choice MS.’

The other Book, which I had also the favour of perusing, namely Horne, was near an Hundred Years older, so named from Andrew Horne, sometime Chamberlain of the City, viz. in the time of King Edward the Second. What this Book contains, is told by this Inscription in one place of it, viz. ‘Iste Liber restat Andreae Horne Piscenario London, de Breggestrete. In quo continentur Cartae, & aliae Consuetudines predict. Civitat. Angliae & Statuta per Henricum Regem, & Edwardum Regem fil. predict. Regis Henrici edita.’ And again, ‘In isto Libro continentur tota Statuta, & Ordinationes & Cartae & Libertates, & Consuetudines Civitat. London & Ordo Justitiorum itinerantium apud Turrim Lond. & ipsum iter.’

5

A larger image is available here.

Another Book also there was in the Chamber, which I also perused for the same purpose, called Liber Custumarum. The First Tract whereof is, de Laudibus Nobilitatis Insulae Britanniae. It is in old French, and consisteth of thirteen chapters; Beginning thus—

6

‘De Britaigne, que ore est appele Engleterre, & qui est si benure sur toutes autres Isles; & qui est si plentiuous de blez & des arbres, & large de boys & de rivers & de veneisons & de oisiaus convenables, et noble de mout de maneres bons chiens. Citees y ad mont belles et bien assises, & belles guameries de terre amyable; close de mere & de douces Ewes delitables: ceo est asavoir, de fluvies, de beaus undes, de clers fountaynes & de douces, &c.’

The writer then applies himself to treat of London; as, the several Charters, the Wards, and the Streets, Passages, and Places there, Privileges of Maiors, &c.

To which I add the Calendarium Cameræ, London, which was also another Book in the Chamber, of use to me also in my searches.”

During the eighteenth century, except for Strype, the archives appear to have been unmolested. Early last century Sir Francis Palgrave made many extracts from this treasury. More recently, M. Auguste Thierry published certain treaties of commerce of the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, between the citizens of London and the merchants of Amiens. In 1843 M. Jules Delpit spent some time at the Guildhall collecting from copies of documents relating to the connections between France and England. Since then the work of publishing and annotating these papers has gone on with great diligence.

A list of the items which comprise the City archives is given by Riley:—

“In addition to the early Registers, or Letter-Books, from A to K inclusive (the respective dates of which are given at the conclusion of this volume), the Record-room at Guildhall contains the following compilations:—Journals and Repertories of the Courts of Aldermen and Common Council from A.D. 1417 down to the present time. Liber de Antiquis Legibus, a Latin Chronicle of the City transactions from A.D. 1178 to 1274, the only one of the records hitherto published. Liber Horn, a miscellaneous collection, date 1311, and compiled probably by its original owner, Andrew Horn. Liber Custumarum, a compilation of a similar nature, date about 1320, and put together probably under the supervision of the same Andrew Horn. Liber Albus. Liber Dunthorn, a compilation in Latin, Anglo-French, and English, prepared between A.D. 1461 and 1490. Liber Legum, a collection of laws from A.D. 1342 to 1590. Liber Ordinationum de Itinere, compiled temp. Edward I.: in addition to which, there are the Assisa Panis, commencing in 1284; Liber Memorandorum, date 1298, and several other manuscript volumes of inferior note and value.

Among the books which are known to have formerly belonged to the Corporation of London, but are now lost, are the following:—Liber Niger Major, and Liber Niger Minor, both quoted in Liber Albus, Speculum, Recordatorium, possibly identical with the Liber Regum Antiquorum, also lost; Magnus Liber de Chartis et Libertatibus Civitatis; Liber Rubeus, and Liber de Heretochiis,7 both mentioned in the Letter-Books, according to M. Delpit, as formerly in existence. It is not improbable that these volumes may have disappeared on the disastrous occasion when, in the reign of Edward VI., the Lord Protector Somerset borrowed three cartloads of books from the Library at Guildhall, none of which were ever returned.”—Riley’s Introduction to Liber Albus.

Since this list was prepared, the Corporation have undertaken the publication of Riley’s Memorials of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Centuries; Sharpe’s Calendar of Wills; the Calendar of Letters; Sharpe’s London and the Kingdom; Price’s Descriptive Account of the Guildhall; Agas’s “Map of London”; Riley’s Chronicles of Old London. In addition to these volumes, one must not omit Arnold’s Chronicle of Customs, published in 1811; the publications of the Camden Society, which include many documents invaluable to the student of City history; other Chronicles translation has made accessible, such as the “Dialogue de Scaccario,” published in full in Stubbs’s Select Charters.

8

CHAPTER II

THE CHARTER OF HENRY THE SECOND

The Charter granted by Henry the Second, though apparently full, contained certain omissions which are significant and important. Round has arranged this Charter side by side with that of Henry the First, dividing their contents into numbered clauses, italicising the points of difference (Geoffrey de Mandeville, pp. 368-369).

| Henry the First | Henry the Second |

|---|---|

| (1) Cives non placitabunt extra muros civitatis pro ullo placito. | (1) Nullus eorum placitet extra muros civitatis Londoniarum de ullo placito praeter placita de tenuris exterioribus, exceptis monetariis et ministris meis. |

| (2) Sint quieti de schot et de loth de Danegildo et de murdro, et nullus eorum faciat bellum. | (2) Concessi etiam eis quietanciam murdri, [et] infra urbem et Portsokna, et quod nullus faciat bellum. |

| (3) Et si quis civium de placitis coronæ implacitatus fuerit, per sacramentum quod judicatum fuerit in civitate, se disrationet homo Londoniarum. | (3) De placitis ad coronam [spectantibus] se possunt disrationare secundum antiquam consuetudinem civitatis. |

| (4) Et infra muros civitatis nullus hospitetur, neque de mea familia, neque de alia, nisi alicui hospitium liberetur. | (4) Infra muros nemo capiat hospitium per vim vel per liberationem Marescalli. |

| (5) Et omnes homines Londoniarum sint quieti et liberi, et omnes res eorum, et per totam Angliam et per portus maris, de thelonio et passagio et lestagio et omnibus aliis consuetudinibus. | (5) Omnes cives Londoniarum sint quieti de theloneo et lestagio per totam Angliam et per portum maris. |

| (6) Et ecclesiæ et barones et cives teneant et habeant bene et in pace socnas suas cum omnibus consuetudinibus ita quod hospites qui in soccis suis hospitantur nulli dent consuetudines suas, nisi illi cujus socca fuerit, vel ministro suo quem ibi posuerit. | (This clause is wholly omitted). |

| (7) Et homo Londoniarum non judicetur in misericordia pecuniæ nisi ad suam were, scilicet ad c solidos, dico de placito quod ad pecuniam pertineat. | (7) Nullus de misericordia pecuniæ judicetur nisi secundum legem civitatis quam habuerunt tempore Henrici regis avi mei. 9 |

| (8) Et amplius non sit miskenninga in hustenge, neque in folkesmote, neque in aliis placitis infra civitatem; et husteng sedeat semel in hebdomada, videlicet die Lunae. | (8) In civitate in nullo placito sit miskenninga; et quod Hustengus semel tantum in hebdomada teneatur. |

| (9) Et terras suas et wardemotum et debita civibus meis habere faciam infra civitatem et extra. | (9) Terras suas et tenuras et vadimonia et debita omnia juste habeant, quicunque eis debeat. |

| (10) Et de terris de quibus ad me clamaverint rectum eis tenebo lege civitatis. | (10) De terris suis et tenuris quæ infra urbem sunt, rectum eis teneatur secundum legem civitatis; et de omnibus debitis suis quae accomodata fuerint apud Londonias, et de vadimoniis ibidem factis, placita [? sint] apud Londoniam. |

| (11) Et si quis thelonium vel consuetudinem a civibus Londoniarum ceperit, cives Londoniarum capiant de burgo vel de villa ubi theloneum vel consuetudo capta fuit, quantam homo Londoniarum pro theloneo dedit, et proinde de damno caperit. | (11) Et si quis in tota Anglia theloneum et consuetudinem ab hominibus Londoniarum ceperit, postquam ipse a recto defecerit Vicecomes Londoniarum namium inde apud Londonias capiat. |

| (12) Et omnes debitores qui civibus debita debent eis reddant vel in Londoniis se disrationent quod non debent. Quod si reddere noluerint, neque ad disrationandum venire, tunc cives quibus debita sua debent capiant intra civitatem namia sua, vel de comitatu in quo manet qui debitum debet. | (12) Habeant fugationes suas, ubicumque habuerunt tempore Regis Henrici avi mei. |

| (13) Et cives habeant fugationes suas ad fugandum sicut melius et plenius habuerunt antecessores eorum, scilicet Chiltre et Middlesex et Sureie. | (13) Insuper etiam, ad emendationem civitatis, eis concessi quod sint quieti de Brudtolle, et de Childewite, et de Yaresive, et de Scotale; ita quod Vicecomes meus (sic) London[iarum] vel aliquis alius ballivus Scotalla non faciat. |

The text of the first is that of Stubbs’s Select Charters; that of the second is taken from the transcript in the Liber Custumarum (collated with the Liber Rubeus).

One very curious mistake was discovered by Round in the first. In clause 9 the word wardemotum is used. This, by comparison with the corresponding clause in the second Henry’s Charter, should be vadimonia: in other words, both Charters confirmed to the citizens “the property mortgaged to them and the debts due to them.”

To consider the differences:—

(1) No citizens are to plead without the walls. The second Charter adds “except in pleas for exterior tenures, my moneyers and servants excepted.”

By the second clause the citizens are freed from Scot and Lot and Danegeld and Murder. Henry the Second substitutes acquittance of murder within the City and Portsoken.

(6) Clause 6 is omitted in the second Charter.

10

(9) Clause 9. I have already shown the error discovered by Round in the word wardemotum.

(10) Here is a limitation, “quæ infra urbem sunt,” which are within the City.

(11) The clause concerning debtors omitted in the second Charter.

(12) About taking toll or any other custom from the citizens: for the “citizens” is substituted the Sheriff.

(13) Observe that Henry the Second does not speak of the Sheriff of London, but of my Sheriff.

The most important omission, however, in the second Charter is that which gives the citizens the right to hold Middlesex on the firma of £300 a year, and the right to elect their own Justiciar and Sheriff.

11

CHAPTER III

THE COMMUNE

We are now in a position to proceed to the establishment of the Commune. The stages of any important reform are, first, the right understanding of the facts; then a tentative discussion of the facts; then an animated discussion of the facts; next, an angry denial of the facts; then a refusal to consider the question of reform at all; finally, the unwilling acceptance of reform with gloomy prophecies of disaster and ruin. One knows nothing about these preliminary stages as regards the great Civic Revolution of 1191. But I am quite sure that, just as it was with the Reform Bill of 1832, so it was with the creation of a Mayor in 1191. There were no newspapers, no pamphlets, and no means of united action except the Folk Mote at Paul’s Cross—which would clearly be of no use on such a point—and the casual meeting day by day of the merchants by the riverside. There was no Royal Exchange; there were no Companies’ Halls for them to meet in; we have no record of any meeting; but we may be sure that the inconvenience of the situation was discussed whenever two or three were gathered together. We may be equally sure that there were Conservatives, those who loved the old days, and dreaded the power of a central authority. Opinion as regards reform has always been divided, and always will be divided; there are always those who would rather endure the ills that exist than meet unknown ills which may be brought upon them by change. I do not know how long the discussions continued and the discontent was endured. On this subject history is dumb. One or two points, however, are certain. The first is that all the great towns of Western Europe were eager for the Commune; the next is the model which they proposed to copy.

It must have been well known to our Kings throughout the twelfth century that the creation of the Commune in the great trading cities of Western Europe was not only ardently desired by the citizens, but had been actually achieved by many. What they desired was a Corporation, a municipality, self-government within their own walls. It is certain that London looked with eyes of envy upon Rouen, a City with which it was closely connected by ties of relationship, as well as those of trade, because Rouen obtained her Commune fifteen years before London obtained the mere shadow of one. It was, in fact, from Normandy that the City derived her12 desire to possess a Commune. The connection between London and Rouen was much closer than we are generally willing to recognise. Communication was easy, the Channel could be crossed whenever the wind was favourable, the Englishman was on a friendly soil when he landed in Normandy, a country ruled by his own Prince. The Normans found themselves also among a friendly people on the soil of England. They came over in great numbers, especially to London. The merchants of Rouen had their port at Dowgate from the days of Edward the Confessor. Many of the leading London merchants came from Rouen and Caen. Therefore, whatever went on in Rouen was known in London. Now, in the year 1145, great and startling news arrived. It was heard that the City of Rouen had obtained a Commune, that is to say, a municipality, with a Mayor for a central authority, and powers of government over the whole City. Further news came that the Commune was established in other parts of France and in the Netherlands, and that everywhere the cities were forming themselves into municipalities, breaking away from the old traditions and organising themselves. This was not done without considerable opposition. The rights of the Church, the rights of the Barons, the rights of the King, were all invaded by the creation of the Commune. It was, however, a great popular movement, irresistible. It succeeded for a time, but in one city after another it fell to pieces. In England it succeeded greatly, and it continued to extend and to flourish. Meanwhile the merchants of London understood very well that, in this respect, what suited the people of Rouen would suit them. Indeed, the conditions were very similar in the two Cities.1

Then began a serious agitation—but not after the modern fashion—among the London citizens in favour of the new civic organisation. Henry the Second would have none of it. In his jealousy of any transfer of power to the people, he allowed no guilds to be formed save with his consent; at one blow he suppressed eighteen “Adulterine” guilds which had thus been created. But he could not suppress the ardent desire of the people for the Commune.

Had the successor of Henry been as wise a King and as clear-sighted as his father, the desire of the City might have been staved off for another generation. But Richard was not Henry. When he was gone upon his crusade, the government was left in the hands of his Chancellor, William Longchamp. And then follows one of those episodes in which the history of London becomes actually the history of the whole country.

Longchamp had become unpopular with all classes. The barons felt the power of his hand and resented it; the merchants found themselves continually subject to extortionate fines, the clergy to exactions. He held all the13 Royal Castles; he was attended by a guard of a thousand horsemen; he affected the parade of royalty. In considering this personage, it must be remembered that he had many enemies in all ranks, and that his character has been chiefly drawn by his enemies. It was, of course, a great point against him—and always hurled in his teeth—that he was of humble origin; he was also, as a matter of course, charged with every kind of immorality. His haughtiness, which might be excused in his position of Viceroy, was undoubted; it was called by his enemies insolence; and there could be no doubt as to the taxes which he imposed. In the letter written by Hugh, Bishop of Coventry, after Longchamp’s deposition, even ecclesiastical invective seems to have done its very worst. The real reason of the deadly hatred is summed up in the following:—

“To omit other matters, he and his revellers had so exhausted the whole kingdom, that they did not leave a man his belt, a woman her necklace, a nobleman his ring, or anything of value even to a Jew. He had likewise so utterly emptied the King’s treasury, that in all the coffers and bags therein, nothing but the keys could be met with, after the lapse of these last two years.” (Roger de Hoveden, Riley’s trans., vol. ii. p. 235.)

From a wax cast in the Guildhall Museum.

On the other hand, Peter of Blois replied to the gentle Bishop of Coventry with a letter which must have awakened in the mind of that prelate something of the ungovernable wrath which belonged to his time. He says:14 “The Bishop of Ely [Longchamp], one beloved by God and men, a man amiable, wise, generous, kind, and meek, bounteous and liberal to the highest degree, had by the dispensations of the Divine favour, and in accordance with the requirements of his own manners and merits, been honoured with the administration of the State, and had thus gained the supreme authority. With feelings of anger you beheld this, and forthwith he became the object of your envy. Accordingly, your envy conceived vexation and brought forth iniquity; whereas he, walking in the simplicity of his mind, received you into the hallowed precincts of his acquaintanceship, and with singleness of heart, and into the bonds of friendship and strict alliance. His entire spirit reposed upon you, and all your thoughts unto him were for evil.” (Roger de Hoveden, Riley’s trans., vol. ii. p. 238.)

We have not to determine the guilt or the innocence of the Chancellor; it is enough to learn that there were opposite views.

The Barons and Bishops were headed by John, Earl of Mortain,2 brother of the King.

It was notorious that of all those who went out to fight the Saracen, few returned. Richard, in the Holy Land, was not sparing himself; it was therefore quite likely that he would meet his death upon the battlefield. Then, as the heir to the crown was a child, and as a man, and not a child, was wanted on the throne, John had certainly every reason to believe that his own accession would be welcomed. He prepared the way, therefore, by joining the popular cause, and put himself at the head of the malcontents.

And now, at last, the citizens saw their chance. They offered to use the whole power of the City for John and the barons, but on conditions. J. H. Round, in his Origin of the Mayoralty of London, p. 3, says:—

“It was at about the same time that the ‘Commune’ and its ‘Maire’ were triumphantly reaching Dijon in one direction, and Bordeaux in another, that they took a northern flight and descended upon London. Not for the first time in her history, the Crown’s difficulty was London’s opportunity, and when in October, 1191, the administration found itself paralysed by the conflict between the King’s brother John, and the King’s representative, the famous Longchamp, London, finding that she held the scales, promptly named the concession of a ‘Commune’ as the price of her support. The chroniclers of the day enable us to picture to ourselves the scene, as the excited citizens who had poured forth overnight, with lanterns and torches, to welcome John to the capital, streamed together on the morning, of the eventful 8th October, at the well-known summons of the great bell, swinging out from its campanile in St. Paul’s Churchyard. There they heard John take the oath to the ‘Commune,’ like a French King or Lord, and then London for the first time had a municipality of her own. What the English and territorial organisation could never have brought about, the foreign Commune, with its commercial basis, could and did accomplish.

And as London alone had her ‘Commune,’ so London alone had her Mayor. The ‘Maire’ was unquestionably imported with the ‘Commune,’ although it is not till the spring of 1193 that the Mayor of London is first mentioned. But already in 1194 we find a citizen accused of boasting that ‘come what may the Londoners shall never have any King but their Mayor.’”

“Not for the first time.” Remember that in 1066, after the battle of Hastings, London only admitted William as King on conditions. London elected Henry the First King on conditions. London made Stephen King on conditions. London received the Empress on conditions; a week later the Queen also on conditions;15 and now, once more, London saw its chance—such a chance as might never occur again—for getting what it wanted—on conditions.

Let us, however, enter more fully into the details of this victory, and into the causes which led to concession.

Longchamp gave the barons an opening by his attempted exclusion of Geoffrey, Archbishop of York (natural brother of the King), from the kingdom, and his forcible seizure of the Archbishop from the very horns of the Altar. Geoffrey complained to John, who gave orders that the Chancellor should stand his trial for the injury he had done to the Archbishop. Remembering the position of Longchamp, as the actual representative of the King, this summons was in the nature of an ultimatum. As regards the City, Longchamp had alienated many of the citizens by his exactions and by the great works which he carried on at the Tower, a point on which the citizens were always extremely jealous.

A day was named for the hearing of the case. The Court, or the Council, sat at Reading. There were present: John, Earl of Mortain; the Archbishop of York as plaintiff; the Archbishop of Rouen—his appearance is most significant, with the bishops and the principal barons of the realm.

But no Chancellor appeared, nor did any message or reply come from him.

The Court being broken up, the barons marched from Reading to Windsor, while the Chancellor retired from Windsor to the Tower of London.

On the day following, the barons marched from Windsor into London. By this statement we may clearly understand that everything had already been arranged with the citizens, otherwise the gates would have been shut. The barons, with their following, were admitted into the City; they held another meeting at the Chapter House of St. Paul’s; and here John, the Archbishops of York and Rouen, and nearly all the bishops and barons of the realm, received the principal citizens, and solemnly granted to the City of London its long-sought Commune, and swore to maintain it firmly so long as it should please the King.

The words of Roger of Hoveden are quite clear; it is extraordinary that there could be any doubt about what was done:

16

“On the same day, also, the Earl of Mortaigne, the Archbishop of Rouen, and the other justiciaries of the King, granted to the citizens of London the privilege of their commonalty; and, during the same year, the Earl of Mortaigne, the Archbishop of Rouen, and the other justiciaries of the King, made oath that they would solemnly and inviolably observe the said privilege, so long as the same should please their lord the King. The citizens of London also made oath that they would faithfully serve their lord King Richard, and his heirs, and would, if he should die without issue, receive Earl John, the brother of King Richard, as their King and Lord.” (Roger de Hoveden, Riley’s trans., vol. ii. p. 230.)

This done, they proceeded without any trouble to depose the Chancellor, who fled, and, after many adventures, got across to Normandy in safety.

Observe the very great importance attached to this step. It was the condition in return for which London joined the barons in getting rid of a rapacious Viceroy; the concession was not lightly, but solemnly, granted, as a measure of the greatest weight, in presence of the chief persons of the kingdom; all present set their hands to the Act; all present swore to maintain it.

One of the chroniclers, Richard of Devizes, a very strong Conservative, shows us what was thought of the step by his party:

“On that very day,” he says, “was granted and instituted the Commune of the Londoners, and the magnates of the whole realm, even the Bishops of the province itself, were compelled to swear to it. London learned now for the first time, in obtaining the Commune, that the realm had no King, for neither Richard nor his father Henry would ever have allowed this to be done, even for a million marks of silver. How great those evils are which spring from a Commune may be understood from the common saying that it puffs up the people and it terrifies the King.”

Ralph de Diceto says more succinctly, “All the before-mentioned magnates [i.e. John, the archbishop, the bishops, earls, and barons] swore [that they would maintain] the Commune of London.” It is he who tells us what the others do not tell us, that this parliament was holden in the Chapter House of Saint Paul, London.

Giraldus Cambrensis says:—

“In crastino vero convocatis in unum civibus, communione, vel ut Latine minus vulgariter magis loquamur, commune seu communia eis concessa et communiter jurata.”

It is therefore abundantly plain that the citizens desired, and obtained from John, the concession of the Commune.

Another chronicler informs us that the Commune was granted to the whole body of citizens gathered together. This means that it was announced at a Folk Mote specially summoned at Paul’s Cross. I cannot but think that the importance of the concession called for the assemblage of the whole people. Mr. Round must be right in his picture. After the meeting in the Chapter House, the Great Bell of St. Paul’s was rung; the people flocked together; the bishop stood up at Paul’s Cross and told them the great news: that they had at last won their community; that for the first time they were one City; that they had for the first time their leader and their speaker.

The City got its Commune. The first Mayor, Henry FitzAylwin, or Henry of London Stone, was elected. Two years afterwards, he is spoken of as the Mayor of London. He held the office for five-and-twenty years: it was twenty-four years after his election that he was recognised by the King. John’s recognition, when17 he was no more than Earl of Mortain, heir to the Crown, was not official. As we have heard already, Richard never recognised either the Commune or the Mayor.

Mr. H. C. Coote, in a paper published by the London and Middlesex Archæological Society, argues that so great a change as that from the former to the later constitution demanded a Charter; that therefore this Charter must have been granted; and that it must have been lost. It is sufficient to note the fact that there is no such Charter. Considering the circumstances, it does not seem as if a Charter could have been granted. The Commune was conferred so long as it should please the King. It did not please the King, who never recognised the Commune. Therefore, one would infer there was no Charter.

In 1215 the citizens obtained from John their right to elect their own Mayor.

As for the meaning of the Commune, Stubbs says:—

“The establishment of the ‘Communa’ of the citizens of London which is recorded by the historians to have been specially confirmed by the Barons and Justiciar on the occasion of Longchamp’s deposition from the Justiciarship is a matter of some difficulty as the word ‘Communa’ is not found in English town-charters, and no formal record of the act of confirmation is now preserved. Interpreted, however, by foreign usage and by the later meaning of the word ‘Communitas’ it must be understood to signify a corporate identity of the municipality which it may have claimed before and which may even have been occasionally recognised but was now firmly established: a sort of consolidation into a single organised body of the variety of franchises, guilds, and other departments of local jurisdiction. It was probably connected with, and perhaps implied by, the nomination of a Mayor who now appears for the first time. It cannot, however, be defined with certainty.” (Stubbs’s Select Charters.)

Now Round3 points out that the words “concessa est communæ Londinensium,” agree exactly with the granting of the French Communes. The same words were used for the Communes of Senlis, of Compiègne, of Abbeville, and of Poitiers. The Commune again, in France, did not necessarily imply the election of a Mayor. At Beauvais and Compiègne at first there was no Mayor.

Round next shows, which is very remarkable, that the long struggle of the citizens to hold the City and County at the firma of £300, which the Crown persistently strove to raise to £500 and more, was terminated in 1191, the year when the Commune was granted, by a return to the old sum of £300. This is a very important fact. Entries of the years 1192 and 1197 show that this yearly sum was maintained at the lower figure. Three points, therefore, are certain:—

1. A Commune was granted to London in 1191.

2. The Firma of City and County was simultaneously lowered from over £500 to the old sum of £300.

3. The Mayor of London first appears in 1193.

It is at this point that an almost contemporary document, discovered by Mr. Round, in the British Museum, which is nothing less than the oath of the Commune, throws a flood of light on the situation.

18

“Sacramentum commune tempore regis Ricardi quando detentus erat Alemaniam (sic).

Quod fidem portabunt domino regi Ricardo de vita sua et de membris et de terreno honore suo contra omnes homines et feminas qui vivere possunt aut mori et quod pacem suam servabunt et adjuvabunt servare, et quod communam tenebunt et obedientes erunt maiori civitatis Lond[onie] et skivin[is] ejusdem commune in fide regis et quod sequentur et tenebunt considerationem maioris et skivinorum et aliorum proborum hominum qui cum illis erunt salvo honore dei et sancte ecclesie et fide domini regis Ricardi et salvis per omnia libertatibus civitatis Lond[onie]. Et quod pro mercede nec pro parentela nec pro aliqua re omittent quin jus in omnibus rebus p[ro]sequentur et teneant pro posse suo et scientia et quod ipsi communiter in fide domini regis Ricardi sustinebunt bonum et malum et ad vitam et ad mortem. Et si quis presumeret pacem domini regis et regni perturbare ipsi consilio domine et domini Rothomagensis et aliorum justiciarum domini regis juvabunt fideles domini regis et illos qui pacem servare volunt pro posse suo et pro scientia sua salvis semper in omnibus libertatibus Lond[onie].” (Round, p. 235.)

Compare this oath with that of a freeman of the present day:—

“I solemnly declare that I will be good and true to our Sovereign Lord King Edward, that I will be obedient to the Mayor of this City, that I will maintain the franchises and customs thereof, and will keep this City harmless in that which in me is; that I will also keep the King’s peace in my own person, that I will know no gatherings nor conspiracies made against the King’s peace, but I will warn the Mayor thereof or hinder it to my power; and that all these points and articles I will well and truly keep according to the laws and customs of this City to my power.”

Again, to quote from Round:—

“For the first time we learn that the government of the City was then in the hands of a Mayor and échevins (skevini). Of these latter officers no one, hitherto, had even suspected the existence. Dr. Gross, indeed, the chief specialist on English municipal institutions, appears to consider these officers a purely continental institution. But in this document the Mayor and échevins do not exhaust the governing body. Of Aldermen, indeed, we hear nothing; but we read of ‘alii probi homines’ as associated with the Mayor and échevins. For these we may turn to another document, fortunately preserved in this volume, which shows us a body of ‘twenty-four’ connected with the government of London some twelve years later (1205-6).

Sacramentum xxiiijor factum anno regni regis Johannis vijo.

Quod legaliter intendent ad consulendum secundum suam consuetudinem juri domini regis quod ad illos spectat in civitate Lond[onie] salva libertate civitatis et quod de nullo homine qui in placito sit ad civitatem spectante aliquod premium ad suam conscientiam reciperent. Et si aliquis illorum donum aut promissum dum in placitum fatiat illud nunquam recipient, neque aliquis per ipsos vel pro ipsis. Et quod illi nullum modum premii accipient, nec aliquis per ipsos vel pro ipsis, pro injuria allevanda vel pro jure sternendo. Et concessum est inter ipsos quod si aliquis inde attinctus vel convictus fuerit, libertatem civitatis et eorum societatem amittet.” (Round, pp. 237-238.)

“Of a body of twenty-four councillors, nothing has hitherto been known. To a body of twenty-five there is this one reference (Liber de Antiq. Leg. Camden Soc. p. 2):

Hoc anno fuerunt xxv electi de discretioribus civitatis, et jurati pro consulendo civitatem una cum Maiore.

The year is Mich. 1200-Mich. 1201; but the authority is not first-rate. Standing alone as it does, the passage has been much discussed. The latest exposition is that of Dr. Sharpe, Records Clerk to the City Corporation (London and the Kingdom, i. 72):

Soon after John’s accession we find what appears to be the first mention of a court of Aldermen as a deliberate body. In the year 1200, writes Thedmar (himself an Alderman), ‘were chosen five-and-twenty of19 the more discreet men of the City and sworn to take counsel on behalf of the City, together with the Mayor. Just as, in the constitution of the realm, the House of Lords can claim a greater antiquity than the House of Commons, so in the City—described by Lord Coke as epitome totius regni—the establishment of a Court of Aldermen preceded that of a Common Council.’”

But they could not have been Aldermen of the wards, simply because the number do not agree.

To find out who they were, we must turn to the foreign evidence. At Rouen the advisers of the Mayor were a body of twenty-four annually elected.

This oath on election was as follows. It will be seen how closely it resembles that of the English Commune—

“(II). De centum vero paribus eligentur viginti quatuor, assensu centum parium, qui singulis annis removebuntur: quorum duodecim eschevini vocabuntur, et alii duodecim consultores. Isti viginti quatuor, in principio sui anni, jurabunt se servaturos jura sancte ecclesie et fidelitatem domini regis atque justiciam quod et ipse recte judicabunt secundum suam conscienciam, etc.

LIV. Iterum, major et eschevini et pares, in principio sui eschevinatus, jurabunt eque judicare, nec pro inimicitia nec pro amicitia injuste judicabunt. Iterum, jurabunt se nullos denarios nec premia capturos, quod et eque judicabunt secundum suam conscienciam.

LV. Si aliquis juratorum possit comperi accepisse premium pro aliqua questione de qua aliquis trahatur in eschevinagio, domus ejus ... prosternatur, nec amplius ille qui super hoc deliraverit, nec ipse, nec heres ejus dominatum in communia habebit.

The three salient features in common are (1) the oath to administer justice fairly; (2) the special provisions against bribery; (3) the expulsion of any member of the body convicted of receiving a bribe.

If we had only ‘the oath of the Commune,’ we might have remained in doubt as to the nature of the administrative body; but we can now assert, on continental analogy, that its twenty-four members comprised twelve ‘skevini’ and an equal number of councillors. We can also assert that it administered justice, even though this has been unsuspected, and may, indeed, at first arouse question.” (Round, p. 240.)

We conclude, therefore, from continental analogy, that the twenty-four of London comprised twelve “skevini” and an equal number of Councillors. What became of this Council?

Round is of opinion, in which most will agree, that this Council was the germ of the Common Council, and he points out that the oath of a member of the Common Council, like that of the ancient Council of twenty-four, still binds him—(1) not to be influenced by private favour; (2) not to leave the Council without the Mayor’s permission; (3) to keep the proceedings secret.

Now the oath of an Alderman (Liber Albus, Riley’s translation, p. 267) is quite different. It is the oath of a Magistrate and superintendent of a ward—

“You shall swear, that well and lawfully you shall serve our lord the King in the City of London, in the office of Alderman in the Ward of N, wherein you are chosen Alderman, and shall lawfully treat and inform the people of the same Ward of such things as unto them pertain to do, for keeping the City, and for maintaining the peace within the City; and that the laws, usages, and franchises of the said City you shall keep and maintain, within town and without, according to your wit and power. And that attentive you shall be to save and maintain the rights of orphans, according to the laws and usages of the said City. And that ready you shall be, and readily shall come, at the summons and warning of the Mayor and ministers of the said City, for the time being, to speed the Assizes, Pleas, and judgments of the Hustings, and other needs of the said City, if you be not hindered by the needs of our lord the King, or by other reasonable cause; and that good lawful counsel you shall give for such things as touch the common profit20 in the same City. And that you shall sell no manner of victuals by retail; that is to say, bread, ale, wine, fish, or flesh, by you, your apprentices, hired persons, servants, or by any other; nor profit shall you take of any such manner of victuals sold during your office. And that well and lawfully you shall (behave) yourself in the said office, and in other things touching the City.—So God you help, and the saints.”4

Again, for English evidence. The City of Winchester shows also the existence of a Council of twenty-four, which continued until 1835:

“Il iert en la vile mere eleu par commun assentement des vint et quatre jures et de la commune ... le quel mere soit remuable de an en an.... Derechef en la cite deinent estre vint et quatre jurez esluz des plus prudeshommes e des plus sages de la ville e leaument eider e conseiller le avandit mere a franchise sauver et sustener.” (Round, p. 242.)

“There shall be in the City a Mayor elected by common consent of the twenty-four ‘Jurats’ and the Commune.... The which Mayor is to be removeable from year to year. Further, in the City there must be twenty-four ‘Jurats’ elected from the most notable and the wisest of the City, both loyally to aid and to counsel the aforesaid Mayor to protect and to maintain the franchise.”

At Winchester the twenty-four retained their distinct position, and it was not till the sixteenth century that the Aldermen were interposed between the Mayor and the Council.

Thus did London get the recognition of its Commune—its community,—and with it the Mayor. There was certainly reason for the suspicion and hostility of the old-fashioned Conservatives towards the new constitution. Some of the citizens, we are told, in the first exuberant joy over their newly-acquired liberties thought that henceforth there would be no need of a King at all. They pictured to themselves a sovereign State like that of Genoa, Pisa, or Venice, in which the City should be independent and separate from the rest of the country. I dare say there were such dreamers. Three years later, in 1194, we hear of citizens who boasted that “come what may, the Londoners shall never have any King but their Mayor.” Fortunately, the Mayor himself observed wiser counsels.

And now we may ask what it was that the City got with its new form of government. The Mayor took over the whole control of trade, which had been in the hands of the mysterious Guild Merchant; but with this vast difference, that he was provided with powers to enforce his ordinances. He took over, in addition, the administration of justice, the maintenance of order in the City, the subjection of all the various Courts and Ward Motes under one Central Court, with its Magistrates, its Bailiffs, its Officers, and its Servants. London as a corporate body actually began in 1191. The Sheriffs lost a great part of their importance; the Aldermen became, but not immediately, Magistrates of the City and not of the Wards only; the citizens themselves began to elect their representatives to rule the City; the regulations of the various crafts passed under the licensing authority of a Judge and his Assessors, who enforced their commands by penalties. In a word, the Commune abolished the ancient treatment of the21 City as an aggregate of private properties, each of which had its own Lord of the Manor, or Alderman, and substituted one great City, presided over by a representative possessed of power and authority, and backed by the strong arm of the law.

After the painting by Ernest Normand in the Royal Exchange, London. By permission of the Artist.

The step, in fact, made the future development of London possible and natural. Wherever there is self-government there is the power of adjusting laws and customs to meet changed conditions. Where there is no self-government there is no such power. A long succession of the wisest and most benevolent Kings would never have done for London what London was thus enabled to do for herself, because, to use the familiar illustration, it is only the foot which knows where the shoe pinches.

We must not claim for the wisdom of our ancestors that London advanced at once, and by a single step, to the full recognition of the possibilities before her. I admit that there were many failures; we know that there were jealousies and animosities; that there were times when the Mayor was unable to cope with the difficulties of the situation—for example, when Edward the First suppressed the Mayoralty altogether, and for eleven years ruled the City strongly and wisely,—but we can claim for the City that there was continuous and steady advance in the direction of orderly and just administration, and that the unity of the City, thus recognised and conceded, became a most powerful factor in the extension and expansion of the City and its trade.

To return to the changes made possible. The chief officer of the City was called a Mayor, after French custom; the Mayor was not appointed by the King; he was elected by the citizens from their own body; his powers were at first indefinite and uncertain; thus, the first act of Edward the Third, a hundred years later, was to make the Mayor one of the Judges of Oyer and Terminer for the trials of criminals in Newgate; the citizens’ right of electing the Mayor was always grudgingly conceded and continually violated. I suppose, next, that the practice of electing the Aldermen, which came in gradually, was accelerated by the natural desire of the citizens to elect all their officers. Another cause was undoubtedly the fact that the manors, or wards, of the City did not continue in the hands of the original families. The holders parted with their property; perhaps they retained certain manorial rights, which were afterwards bought out. The wards in which this happened began to elect their Aldermen; by the year 1290 there were only four wards still named after the Lords of the Manor. And it seems reasonable that, as soon as the City had a recognised head and chief under the King, he would be considered first, so that the Bishop’s Aldermanry naturally fell into abeyance. Certainly we find no more Charters addressed to the Bishop. The first Mayor remained Mayor for twenty-five years; that is to say, for life. It is natural to suppose that he was at first put22 forward on occasion as the City’s spokesman, as well as its chief officer. It is not absolutely certain that the Mayor was first appointed in 1191, when John granted the “Commune.” In some French towns the Mayor, as we have seen, came after the Commune, but he is mentioned in 1193. In 1194 Richard’s Charter makes no mention of the Mayor; he existed, certainly, but he was not yet acknowledged. In 1215—May 8th—John conceded the citizens the privilege of electing their Mayor.

This concession to London was followed by the same concession to other cities and towns of England. The Commune or municipality of London became the model for all other municipalities granted to other towns. It is also the model for all municipalities created wherever our race settles itself, and wherever an English-speaking town is founded. This fact makes the history we have just considered of the most vital interest and importance to every citizen or burgess in whatever town is governed by Mayor, Aldermen, and the Court of Common Council.

I cannot do better than sum up these notes on the changes effected by the Commune with another quotation from Dean Stubbs:—

“The Communa of London, and of those other English towns which in the twelfth century aimed at such a constitution, was the old English guild in a new French garb; it was the ancient association, but directed to the attainment of municipal rather than mercantile privileges; like the French communa, it was united and sustained by the oaths of its members and of those whom it could compel to support it. The mayor and the jurati, the mayor and jurats, were the framework of the communa, as the aldermen and brethren constituted the guild, and the reeve and good-men the magistracy of the township. And the system which resulted from the combination of these elements, the history of which lies outside our present period and scope, testifies to their existence in a continued life of their own. London, and the municipal system generally, has in the mayor a relic of the communal idea, in the alderman the representative of the guild, and in the councillors of the wards, the successors to the rights of the most ancient township system. The jurati of the Commune, the brethren of the guild, the reeve of the ward, have either disappeared altogether, or taken forms in which they can scarcely be identified.”

We have spoken of the first Mayor of London, and what we know about him has been summed up by Round for the Dictionary of National Biography. We do not know his parentage. It has been conjectured that he was the grandson of Leofstan, Portreeve of London before the Conquest. But there were three or four Leofstans. It is suggested by Stubbs that he was descended from Ailwin Child, who founded or endowed Bermondsey Abbey in 1082. It is also suggested that he was an hereditary Baron of London. In the “Pipe Roll” of 1165, a Henry FitzAylwin, Fitz Leofstan, with Alan his brother, pay for succeeding to land in Essex or Hertfordshire. Now FitzAylwin the Mayor did hold land in Hertfordshire by tenure of serjeantry. The name appears in four documents as Henry Fitz Ailwin, or Æthelwine, before he was Mayor, and in many documents after he was Mayor. In the former name the latest date is 30th November 1191,23 and under the latter the first is April 1193. It would therefore seem as if the Mayoralty was not established at first on the concession of the grant. It may well be that it took time for the citizens to assume their full organisation. We may fairly assume that his office, if not his election, dates from the day of that concession.

FitzAylwin was one of the Treasurers for the King’s ransom in 1194. He was also called Henry of London Stone, because his house stood on the north side of Candlewick Street, near St. Swithin’s Church, over against London Stone. He presided over a meeting of citizens on 24th July 1212, and died a few weeks later. He left children from whom many persons can still trace descent. Among them, as the two living representatives of the first Mayor, are, I believe, Lady Beaumont and the Earl of Abingdon. Fifty years ago a learned antiquary, Stapleton, drew up a list of all the descendants of Henry FitzAylwin.

King Richard took no hostile proceedings against the Mayoralty. He never recognised it; but he never tried to abolish it, and as the enemies of the Commune observed that nothing disloyal to the King, nothing dangerous to the Church, was set up in the City, they learned to regard the institution without disfavour or suspicion, so that when the Mayoralty was at last recognised by King John, there was no longer any hostility, or even any misgiving. The old order had passed, giving way to the new. How necessary this new order was; how it fitted in with the old order, so that there was revolution without dislocation, is proved by its adoption in all our towns and cities, by its long continuance, and by its present vitality.

24

CHAPTER IV

THE WARDS

The large area included by the Roman Wall was parcelled out, after the Saxon occupation, into manors, socs, or estates, held by private persons. Some of them passed into the possession of the Church; some into possession of the City; some changed hands. That these manors included the most densely populated parts of the City, or Thames Street, and the streets north of that main artery, proves that the first allotment took place very early in the Saxon occupation, when the City was still deserted; this fact, indeed, affords another proof of that desertion, because we cannot believe that a populous quarter, covered with warehouses and merchants’ residences, should have been assigned to one man or to a dozen men. The value of the manor, comprising gardens lying among ruined foundations, shut off from the river and its fish by a high and thick stone wall, could have been no more than that of a manor lying beside the north wall, on which corn was growing and orchards were planted. Just as the Bedford Estate in London began with the fields of Bloomsbury; just as the Westminster Estate began with the marshes round Thorney Island, so the original manors of London, at first gardens and wastes, became built over or sold for building purposes. What, then, were manorial rights? Let us read the instructions of Archdeacon Hall on this point. He says:—

25

“Manorial property was a possession differing in many respects from what is now called landed estate. It was not a breadth of land, which the lord might cultivate or not as he pleased, suffer it to be inhabited, or reduce it to solitude and waste; but it was a dominion or empire, within which the lord was the superior over subjects of different ranks, his power over them not being absolute, but limited by law and custom. The lord of a manor, who had received by grant from the crown, saca and soca, tol and team, was not merely a proprietor, but a prince; and his courts were not only courts of law, but frequently of criminal justice. The demesne, the assised, and the waste lands were his; but the usufruct of the assised land belonged, on conditions, to the tenants, and the waste lands were not so entirely his, that he could exclude the tenants from the use of them. It was this double capacity, in which the lord stood, to his tenants, as the arbiter of their rights, as well as the owner of the land, which rendered it necessary to the due discharge of the duty of his station, that the lord of a manor should be such a person as Fleta describes: Truthful in his words, faithful in his actions, a lover of justice and of God, a hater of fraud and wrong, since it most concerns him not to act with violence, or according to his own will, but to follow advice, not being guided by some young hanger-on, some jester or flatterer, but by the opinion of persons learned in the law, men faithful and honest, and of much experience. Manors were petty royalties; the court and household of the lord resembling in some degree that of the King. In Fleta an account is given of the officers of the royal household, the Senescallus Hospitii Regis, who held his court in the palace; the Marescallus, the Camerarius, the Clericus panetarii; but in the latter part of the book, which treats of the management of manors, we find the lord of the manor attended by the Senescallus, who held his courts, by the Marescallus, who had the charge of his stud, and by the Coquus, who rendered an account of the daily expenditure to the Senescallus.”

Drawn by Schnebbelie and engraved by Warren for Dr. Hughson’s Description of London.

Some of these manors belonged to the Bishop or to a Church or to a religious foundation, but the rights and the government and the management of all were alike. Again to quote Archdeacon Hall:—

“Manors, whether royal and baronial, or episcopal and ecclesiastical, were to their owners sources of wealth, derived from two distinct sources—the exercise of a legal jurisdiction and the rent of cultivation26 of land. The Ecclesiastical Manors differed in no respect from those which were in lay hands. They were the sources of income, not the field of spiritual labour. They contributed to the support of the Bishop or of the Chapter, and of the religious household of the Cathedral, by profits and revenues no way different from those derived by the Sovereign and the Lords from other Manors. It is remarkable that neither the Exchequer Domesday, nor the Domesday of St. Paul’s contains any evidence, that the Ecclesiastical Manors had any superior religious privileges, or were the centres from which religious knowledge was diffused to the neighbourhood. The Manors of the religious houses were in reality secular possessions; and their history, as shown in the Domesday of St. Paul’s, is valuable as illustrating the social, rather than the religious, condition of the time.”

It must be noted, however, that none of the City manors were royal; nor did any of their manors at any time belong to any noble great or small. The nobles had their town houses, many of them large and stately palaces covering a broad area, but they were never Lords of any London Manor. And the Church property in the City included, after a time, only the site of the various religious foundations and the house property which they happened to possess. The Ward of Portsoken, of which mention has already been made, is the only exception to this rule.

The manors, then, became the wards of the City.

The earliest list of the wards is contained in a document found among the archives of St. Paul’s, entitled: “The measurements of the land of St. Paul’s within the City of London.” The date is early in the twelfth century.

The list is not, unfortunately, complete; nor can all the wards be identified. But it is most valuable for what it does contain. A facsimile is published in J. E. Price’s Guildhall. Thus, the first ward is “Warda Episcopi,” the Bishop’s Ward, Cornhill. Then we have Warda Haco, i.e. of St. Nicholas of Acon, in Lombard Street; Warda Alwold (Cripplegate); Warda Fori—of the Market-place—Chepe; Warda Ralph, son of Algod; Warda Osbert Dringepinne; Warda Hugh, son of Ulgar; Warda Brocesgange; Warda Liured; Warda Reimund; Warda Herbert; Warda Edward, son of Wizel; Warda Sperling; Warda Brichmar the Moneyer; Warda Brichmar the Cottager; Warda Godwin, son of Esgar; Warda Alegate; Warda Rolf, son of Liviva; Warda Algar Manningestepsunne; Warda Edward Parole.5

There are twenty wards in all. It will be observed that they are all named after single persons except the Ward of the Market Place and the Ward of Alegate. These single persons were the proprietors, the barons, the owners of the land; the wards were the private manors into which the City was divided. (See Appendix I.)

27

It is impossible to say how many wards there were in the whole City. The owners were barons of right, a rank which afterwards descended to their successors, the elected Aldermen. The first governing body of London consisted of the owners of these estates, to whom were added the more important merchants. In the changes and chances of fortune, the estates changed hands; families died out and were replaced; we find, in the fourteenth century, for instance, that all the old families, whose names we know, had by that time disappeared, left the City, or become merged in the general population. But the manors themselves seem to have remained for the most part unbroken. It is difficult even at the present day to cut up a manor. The Lord of the Manor, called the Alderman, formed part of the ruling body by virtue of possession. In other words, the government of London, despite the survival of the Folk Mote, was a territorial aristocracy. In the Liber Albus (p. 30), Carpenter calls attention to the fact that although in his day—the beginning of the fifteenth century—the wards were known by their own names, they had formerly borne the names of their Aldermen. Thus, he says that the Ward of Candelwyk Street was formerly the Ward of Thomas Basyng; the Ward of Castle Baynard was the Ward of Simon Hadestok; Tower Ward was the Ward of Henry le Frowyk; Vintry Ward was the Ward of Henry le Covyntre; Farringdon Ward Without was the Ward of Anketill de Auvern. So also, as W. J. Loftie points out, the Ward of the Bridge was at one time that of John Horn; the Cordwainers’ Ward was that of Henry le Waleys; Langbourne Ward that of Nicolas de Winton; Aldgate that of John of Northampton; Walbrook of John Adrian; Broad Street of William Bukerel; Aldersgate of Wolman de Essex; Bread Street of William de Denham. Not one of these names can be found in the list just quoted.

By the time of Carpenter, the wards were clearly defined. Up to the reign of Edward the First their boundaries were unsettled.

The Ward Mote has been held from time immemorial, according to Stow. That is to say, whenever a manor became settled and populated, it was the interest of the Alderman to have a court of Assistants who could act as his Police, his Constables, his Detectives.

At what period the Aldermen ceased to be hereditary and were elected by the citizens, I know not. The election of Aldermen is not contemplated in the Charters of Henry the First, Henry the Second, Richard the First, or John. In the second Charter of Henry the Third, the Barons (i.e. Aldermen) of the City are appointed to elect the Mayor. In the Charter of Edward the Second it is provided that the Aldermen shall be “removable yearly and be removed on the day of St. Gregory (the 12th of March) and in the year following shall not be re-elected, but others shall be elected in their stead.” (Liber Albus.)

In the year 1354 the old order was restored, and the Aldermen remained in office for life.

28

The following is a list of the twenty-four wards into which London was divided before the end of the thirteenth century, with the names of the respective Aldermen:—

| Warda | Fori | Alderman. | Stephen Aswy. |

| „ | Ludgate and Newgate | „ | William de Farndon. |

| „ | Castle Baynard | „ | Richard Aswy. |

| „ | Aldersgate | „ | William le Mazener. |

| „ | Bredstrete | „ | Ducan de Botevile. |

| „ | Quenehythe | „ | Simon de Hadestucke. |

| „ | Vintry | „ | John de Gisors. |

| „ | Dougate | „ | Gregory de Rockesley. |

| „ | Walbrook | „ | Thomas Box. |

| „ | Coleman Street | „ | John Fitz Peter. |

| „ | Bassishaw | „ | Radulpus le Blound. |

| „ | Cripplegate | „ | Henry Frowick. |

| „ | Candlewyk Street | „ | Robert de Basing. |

| „ | Langeford | „ | Nicholas de Winton. |

| „ | Cordewene Street | „ | Henry le Waleys. |

| „ | Cornhill | „ | Martin Box. |

| „ | Lime Street | „ | Robert de Rockesley. |

| „ | Bishopsgate | „ | Philip le Taylour. |

| „ | Alegate | „ | John de Northampton. |

| „ | Tower | „ | William de Hadestock. |

| „ | Billingsgate | „ | Wolman de Essex. |

| „ | Bridge | „ | Joseph de Achatur. |

| „ | Lodyngebery | „ | Robert de Arras. |

| „ | Portsoken | „ | Trinity. |

In this list we observe that Cheap Ward is still called Ward Fori; Langbourne Ward appears as Langeford; Broad Street Ward is Lodyngebery; Farringdon is Ludgate and Newgate Ward; Aldgate is Alegate. Forty years later there is found another list of wards in which the modern names appear with the exception of Alegate which is written Algate. The names of the wards are in four cases derived from the trades carried on in them: in four cases from the chief families in them: in the rest from buildings or monuments belonging to them. The names of the Aldermen show sixteen belonging to the old ruling families: seven belonging to new families or to trades, and one, the Prior of Holy Trinity, as an official Alderman.

The date of this list of wards and Aldermen is probably somewhere about 1290, nearly two hundred years after the first list. We have, then, the old City families still represented among the Aldermen. Were they elected? It is impossible to say how long the hereditary system was maintained, and when it was replaced by the elective system. The revolution was a peaceful and bloodless one, since there is no record of it. William Farringdon, who bought his ward, and his son Nicholas, were successive Aldermen of the ward for no less than eighty-two years.

29

The change of the names in the wards seems to have been carried out between the year 1272, when Riley’s Memorials begin, and 1314, when a list of wards appears with the names that belong to the street or quarter.

Thus we have6:—

| 1272. | Ward of Thomas de Basinge (Bridge Ward). |

| 1276. | „ „ Castle Baynard. |

| 1277. | „ „ William de Hadestok (Tower Ward). |

| „ | „ „ Portsoken. |

| „ | „ „ Henry de Coventre (Vintry Ward). |

| „ | „ „ Anketill de Auverne (Farringdon Ward Without). |

| „ | „ „ Henry le Waleys (Cordwainers’ Ward). |

| 1278. | „ „ John Adrien (Walbrook Ward). |

| „ | „ „ Chepe. |

| „ | „ „ William Bukerel (Broad Street Ward). |

| „ | „ „ John de Blakethorn (Aldersgate Ward). |

| „ | „ „ Henry de Frowyk (Cripplegate Ward). |

| „ | „ „ Ralph le Fever (Farringdon Within). |

| 1283. | „ „ William de Farndon (Farringdon Within).7 |

| 1291. | „ „ Walbrook (see above). |

| „ | „ „ Cornhill. |

| 1295. | „ „ Broad Street (see above). |

| „ | „ „ Bishopsgate. |

| 1300. | „ „ Bassieshaw. |

| „ | „ „ Coleman Street. |

| 1303. | „ „ Crepelgate. |

| „ | „ „ Langeburne. |

| „ | „ „ Tower Ward (see above). |

| 1310. | „ „ Without Ludgate (Farringdon Without). |

| 1311. | „ „ Dowgate. |

| „ | „ „ Vintry (see above). |

| „ | „ „ Aldersgate. |

| „ | „ „ Cordwainer Street (see above). |

| „ | „ „ Bread Street. |

| „ | „ „ Lyme Street. |

| „ | „ „ Candelwick Street. |

| „ | „ „ Bridge Ward (see above). |

| 1312. | „ „ Queen Hythe. |

From this list, it appears that between 1272 and 1283, of fourteen wards named in the Memorials, three only have the name of their street or quarter, the rest being all named after their Aldermen. But from 1283 to 1314 there are nineteen wards mentioned, and they are all named after their street or district. It is therefore safe to conclude that within these forty years the aldermanry had ceased to be proprietary or hereditary. We may connect this fact with the story of Walter Hervey’s election in 1272 (see p. 52), which proves that the oligarchy had already lost much of their power.

30