St Pauls, Index

CHAPTER IV.

HISTORICAL MEMORIES TO THE ACCESSION OF THE TUDORS.

The First Cathedral—Mellitus and his Troubles—Erkenwald—Theodred "the Good"—William the Norman, his Epitaph—The Second Cathedral—Lanfranc and Anselm hold Councils in it—Bishop Foliot and Dean Diceto—FitzOsbert—King John's Evil Reign, his Vassalage—Henry III.'s Weak and Mischievous Reign—The Cardinal Legate in St. Paul's—Bishop Roger "the Black"—The three Edwards, Importance of the Cathedral in their Times—Alderman Sely's Irregularity—Wyclif at St. Paul's—Time of the Wars of the Roses—Marriage of Prince Arthur.

I have already said that the buildings of the ancient cathedral, with a special exception to be considered hereafter, were completed before the great ecclesiastical changes of the sixteenth century.

Our next subject will be some history of the events which the cathedral witnessed from time to time during its existence, and for this we have to go back to the very beginning, to the first simple building, whatever it was, in which the first bishop, Mellitus, began his ministry. He founded the church in 604, and he had troubled times. The sons of his patron, King Sebert, relapsed into paganism, indeed they had never forsaken it, though so long as their father lived they had abstained from heathen rites. One day, entering the church, they saw the bishop celebrating the Sacrament, and said, "Give us some of that white bread which you gave our father." Mellitus replied that they could not receive it before they were baptized; whereupon they furiously exclaimed that he should not stay among them. In terror he fled abroad, as did Justus from Rochester, and as Laurence would have done from Canterbury, had he not received a Divine warning. Kent soon returned to the faith which it had abandoned; but Essex for a while remained heathen, and when Mellitus wished to return they refused him, and he succeeded Laurence at Canterbury. Other bishops ministered to the Christians as well as they could; but the authority of the See and the services of the cathedral were restored by Erkenwald, one of the noblest[page 24] of English prelates, son of Offa, King of East Anglia. He founded the two great monasteries of Chertsey and Barking, ruled the first himself, and set his sister Ethelburga over the other. In 675 he was taken from his abbey and consecrated fourth Bishop of London by Archbishop Theodore, and held the See until 693. He was a man, by universal consent, of saintly life and vast energy. He left his mark by strengthening the city wall and building the gate, which is called after him Bishopsgate. Close by is the church which bears the name of his sister, St. Ethelburga. He converted King Sebba to the faith; but it was probably because of his beneficent deeds to the Londoners that he was second only to Becket in the popular estimate, all over southern England. There were pilgrimages from the country around to his shrine in the cathedral, special services on his day, and special hymns. In fact, as in the case of St. Edward, there were two days dedicated to him, that of his death, April 30, and that of his translation, November 14, and these days were classed in London among the high festivals. His costly shrine was at the back of the screen behind the high altar. The inscription upon it, besides enumerating the good deeds we have named, said that he added largely to the noble buildings of the cathedral, greatly enriched its revenues, and obtained for it many privileges from kings. His name, so far as its etymology is concerned, found its repetition in Archibald, Bishop of London, 1856-1868, the founder of the "Bishop of London's Fund."

Another bishop of these early times was Theodred, who was named "the Good." We cannot give the exact dates of his episcopate, further than that he was in the See in the middle of the tenth century, as is shown by some charters that he witnessed. There is a pathetic story told of him that on his way from London to join King Athelstan in the north he came to St. Edmund's Bury, and found some men who were charged with robbing the shrine of St. Edmund, and were detected by the Saint's miraculous interference. The bishop ordered them to be hanged; but the uncanonical act weighed so heavily on his conscience that he performed a lifelong penance, and as an expiation reared a splendid shrine over the saint's body. And further, he persuaded the King to decree, in a Witanagemote, that no one younger than fifteen should be put to death for theft. The bishop was buried in the crypt of St. Paul's,[page 25] and the story was often told at his tomb, which was much frequented by the citizens, of his error and his life-long sorrow.

Another bishop who had been placed in the See by Edward the Confessor, who, it will be remembered, greatly favoured Normans, to the indignation of the English people, was known as "William the Norman," and, unpopular as the appointment may have been, it did the English good service. For when the Norman Conquest came the Londoners, for a while, were in fierce antagonism, and it might have gone hard with them. But Bishop William was known to the Conqueror, and had, in fact, been his chaplain, and it was by his intercession that he not only made friends with them, but gave them the charter still to be seen at the Guildhall. His monument was in the nave, towards the west end, and told that he was "vir sapientia et vitæ sanctitate clarus." He was bishop for twenty years, and died in 1075. The following tribute on the stone is worth preserving:—

"Hæc tibi, clare Pater, posuerunt marmora cives,

Præmia non meritis æquiparanda tuis:

Namque sibi populus te Londoniensis amicum

Sensit, et huic urbi non leve presidium:

Reddita Libertas, duce te, donataque multis,

Te duce, res fuerat publica muneribus.

Divitias, genus, et formam brevis opprimat hora,

Hæc tua sed pietas et benefacta manent."1

To his shrine also an annual pilgrimage was made, and Lord Mayor Barkham, on renewing the above inscription A.D. 1622, puts in a word for himself:

"This being by Barkham's thankful mind renewed,

Call it the monument of gratitude."

We pass on to the time of the "second church," the Old[page 26] St. Paul's which is the subject of this monograph.

The importance of London had been growing without interruption ever since its restoration by King Alfred, and it had risen to its position as the capital city. This largely showed itself when Archbishop Lanfranc, in 1075, held a great council in St. Paul's, "the first full Ecclesiastical Parliament of England," Dean Milman calls it. Up to that time, secular and Church matters had been settled in the same assembly, but this meeting, held with the King's sanction, and simultaneously with the Witan, or Parliament, established distinct courts for the trial of ecclesiastical causes. It decreed that no bishop or archdeacon should sit in the shiremote or hundred-mote, and that no layman should try causes pertaining to the cure of souls. The same council removed some episcopal sees from villages to towns, Selsey to Chichester, Elmham first to Thetford, then to Norwich, Sherburn to Old Sarum, Dorchester-on-Thame to Lincoln.

Another council of the great men met in St. Paul's in the course of the dispute between Henry I. and Anselm about the investitures, but it ended in a deadlock, and a fresh appeal to the Pope.

In the fierce struggle between Henry II. and Archbishop Becket, Gilbert Foliot, Bishop of London, while apparently quite honest in his desire to uphold the rights of the Church, also remained in favour with the King, and hoped to bring about peace. Becket regarded Foliot as his bitter enemy, and, whilst the latter was engaged in the most solemn service in St. Paul's (on St. Paul's Day, 1167), an emissary from the Archbishop, who was then in self-imposed exile abroad, came up to the altar, thrust a sentence of excommunication into his hands, and exclaimed aloud, "Know all men that Gilbert, Bishop of London, is excommunicated by Thomas, Archbishop of Canterbury." When Becket returned to England, December 1st, 1170, after a hollow reconciliation with the King, he was asked to remove his sentence of excommunication on Foliot and the Bishops of Salisbury and York, who had, as he held, usurped his authority. He refused, unless they made acknowledgment of their errors. The sequel we know. The King's hasty exclamation on hearing of this brought about the Archbishop's murder on the 29th of the same month. During the excommunication, Foliot seems to have behaved wisely and[page 27] well. He refused to accept it as valid, but stayed away from the cathedral to avoid giving offence to sensitive consciences. After Becket's murder, he declared his innocence of any share in it, and the Bishop of Nevers removed the sentence of excommunication.

It was at this period that the Deanery was occupied by the first man of letters it had yet possessed, Ralph de Diceto. His name is a puzzle; no one has as yet ascertained the place from which it is taken. Very probably he was of foreign birth. When Belmeis was made Bishop of London in 1152, Diceto succeeded him as Archdeacon of Middlesex. His learning was great, and his chronicles (which have been edited by Bishop Stubbs) are of great historical value. In the Becket quarrel Diceto was loyal to Foliot, but he also remained friendly with Becket. In 1180, he became Dean of St. Paul's. Here he displayed great and most valuable energy; made a survey of the capitular property (printed by the Camden Society under the editorship of Archdeacon Hale), collected many books, which he presented to the Chapter, built a Deanery House, and established a "fratery," or guild for the ministration to the spiritual and bodily wants of the sick and poor. He died in 1202. He wrote against the strict views concerning the celibacy of the clergy promulgated by Pope Gregory VII., and declared that the doctrine and the actual practice made a great scandal to the laity. Dean Milman suspects that he was much moved herein by the condition of his own Chapter.

In 1191, whilst King Richard I. was in Palestine, his brother John summoned a council to St. Paul's to denounce William de Longchamp, Bishop of Ely, to whom Richard had entrusted the affairs of government, of high crimes and misdemeanours. The result was that Longchamp had to escape across sea. At length the King returned, but the Londoners were deeply disaffected. William FitzOsbert, popularly known as "Longbeard," poured forth impassioned harangues from Paul's Cross against the oppression of the poor, and the cathedral was invaded by rioters. Fifty-two thousand persons bound themselves to follow him, but Hubert, Archbishop of Canterbury, met the citizens in the cathedral, and by his mild and persuasive eloquence persuaded them to preserve the peace. FitzOsbert, finding himself deserted, clove the head of the man sent to arrest him, and shut himself up in the[page 28] church of St. Mary-le-Bow. His followers kept aloof, and a three-days' siege was ended by the church being set on fire. On his attempt to escape he was severely wounded by the son of the man he had killed, was dragged away, and burned alive. But his memory was long cherished by the poor. Paul's Cross was silent for many years from that time.

In 1213, a great meeting of bishops, abbots, and barons met at St. Paul's to consider the misgovernment and illegal acts of King John. Archbishop Langton laid before the assembly the charter of Henry I., and commented on its provisions. The result was an oath, taken with acclamation, that they would, if necessary, die for their liberties. And this led up to Magna Charta. But it was a scene as ignominious as the first surrender before Pandulf, when Pope Innocent accepted the homage of King John as the price of supporting him against his barons, and the wretched King, before the altar of St. Paul, ceded his kingdom as a fief of the Holy See. The Archbishop of Canterbury protested both privately and publicly against it.

Henry III. succeeded, at the age of ten years, to a crown which his father had degraded. The Pope addressed him as "Vassallus Noster," and sent his legates, one after another, to maintain his authority. It was in St. Paul's Cathedral that this authority was most conspicuously asserted. Before the high altar these legates took their seat, issued canons of doctrine and discipline, and assessed the tribute which clergy and laity were to pay to the liege lord enthroned at the Vatican. But the indignation of the nation had been waxing hotter and hotter ever since King John's shameful surrender. Nevertheless, in the first days of the boy King's reign, the Papal pretensions did good service. The barons, in wrath at John's falseness, had invited the intervention of France, and the Dauphin was now in power. In St. Paul's Cathedral, half England swore allegiance to him. The Papal legate, Gualo, by his indignant remonstrance, awoke in them the sense of shame, and the evil was averted. Then another council was held in the same cathedral, and the King ratified the Great Charter.

Henry III. grew to manhood, and gave himself up to the management of foreign favourites, and in 1237, instigated by these, who were led by Peter de la Roche, Bishop of Winchester, he invited Pope Gregory IX. to[page 29] send a Legate (Cardinal Otho "the White") to arrange certain matters concerning English benefices, as well as some fresh tribute. They called it "promoting reforms." Their object was to support him in filling all the rich preferments with the Poitevins and Gascons whom he was bringing over in swarms. The Cardinal took his lofty seat before the altar of S. Paul's, and the King bowed before him "until his head almost touched his knees." The Cardinal "lifted up his voice like a trumpet" and preached the first sermon of which we have any report in St. Paul's. His text was Rev. iv. 6, and he interpreted "the living creatures" as the bishops who surrounded his legatine throne, whose eyes were to be everywhere and on all sides. The chroniclers tell how a terrific storm burst over the cathedral at this moment, to the terror of the whole congregation, including the Legate, and lasted for fifteen days. It did much harm to the building. The bishop, Roger Niger, exerted himself strenuously in repairing this. Edmund Rich, the Archbishop of Canterbury, indignantly protested against the intrusion of foreign authority, and was joined by Walter de Cantelupe, the saintly Bishop of Worcester, but for a long time they were powerless. Besides direct taxation, wealth raised from the appropriation of rich canonries was drained away from church and state into the Papal treasury. The Legate remained for four years in power. The Archbishop, in despair, retired abroad, and died as a simple monk at Pontigny. The Bishop of London, Roger Niger, was so called from his dark complexion, and people whimsically noted his being confronted with the Cardinal Otto Albus. Bishop Roger, before his episcopate, was Archdeacon of Rochester, a very wise and energetic administrator. He was now on the side of Rich, bent on defending his clergy from being over-ridden by the foreigners. He exerted himself as bishop not only to repair the mischief done by the storm, but to enlarge and beautify the still unfinished structure. Fourteen years later King Henry was offering devotion at the shrine of Rich, for he had been canonised, and that on the strength of his having resisted the King's criminal folly in betraying the rights of his people; for by this time the nation was aroused. The Londoners rose and burned the houses of the foreigners. Bishop Roger, though he, of course, declared against the scenes of violence, let it be seen that he was determined, by constitutional methods, to defend his clergy from being plundered.[page 30] On his death, in 1241, there was a long vacancy, the King wanting one man and the canons determined on another, and they carried their man, Fulk Bassett, though he was not consecrated for three years. Pope Innocent IV., in 1246, sent a demand of one-third of their income from the resident clergy, and half from non-resident. Bishop Fulk indignantly called a council at St. Paul's, which declared a refusal, and even the King supported him. The remonstrance ended significantly with a call for a General Council. But he was presently engaged in a more serious quarrel. The King forced the monks of Canterbury, on the death of Edmund Rich, to elect the queen's uncle, Boniface of Savoy, to the primacy. He came and at once began to enrich himself, went "on visitation" through the country demanding money. The Dean of St. Paul's, Henry of Cornhill, shut the door in his face, Bishop Fulk approving. The old Prior of the Monastery of St. Bartholomew, Smithfield, protested, and the Archbishop, who travelled with a cuirass under his pontifical robe, knocked him down with his fist.2 Two canons, whom he forced into St. Paul's chapter, were killed by the indignant populace. The same year (1259) brave Bishop Fulk died of the plague. For years the unholy exactions went on, and again and again one has records of meetings in St. Paul's to resist them.

When Simon de Montfort rose up against the evil rule of Henry III. the Londoners met in folkmote, summoned by the great bell of St. Paul's, and declared themselves on the side of the great patriot. They are said to have tried to sink the queen's barge when she was escaping from London to join the King at Windsor.

King Edward I. demanded a moiety of the clerical incomes for his war with Scotland. The Dean of St. Paul's (Montfort) rose to protest against the exaction, and fell dead as he was speaking. Two years later, the King more imperiously demanded it, and Archbishop Winchelsey wrote to the Bishop of London (Gravesend) commanding him to summon the whole of the London clergy to St. Paul's to protest, and to publish the famous Bull, "clericis laicos," of Pope Boniface VIII., which forbade any emperor, king, or prince to tax the clergy without express leave of the Pope. Any layman who exacted, or any cleric who paid, was at once excommunicate. Boniface, who had been pope two years, put[page 31] forward far more arrogant pretensions than Gregory or Innocent had done, but times were changed. The Kings of England and France were at once in opposition. The latter (Philip IV.) was more cautious than his English neighbour, and in the uncompromising struggle between king and pope, the latter died of grief at defeat, and his successor was compelled, besides making other concessions, to remove the papal residence from Rome to Avignon, where it continued for seventy years, the popes being French nominees. King Edward, with some trouble, got his money, but promised to repay it when the war was over, and the clergy succeeded in wresting some additional privileges from him, which they afterwards used to advantage.

We pass over the unhappy reign of Edward II., only noting that the Bishop of Exeter, Stapylton, who was ruling for him in London, was dragged out of St. Paul's, where he had taken sanctuary, and beheaded in Cheapside. He was the founder of Exeter College, Oxford.

The exile of the popes to Avignon, so far from diminishing their rapacity, increased it, if possible, and Green shows that the immense outlay on their grand palace there caused the passing of the Statute of Provisors in 1350, for the purpose of stopping the incessant draining away of English wealth to the papacy. During that "seventy years' captivity," as it was called, Italy and Rome were revolutionised, and when at length the popes returned to their ancient city (1376) the great "papal schism" began, which did so much to bring on the Reformation. It arose out of the Roman people's determination to have an Italian pope, and the struggle of the French cardinals to keep the dignity for Frenchmen. The momentous results of that fierce conflict only concern us here indirectly. We simply note now that the year following the return to Rome saw John Wyclif brought to account at St. Paul's.

But before following that history, it will not be out of place to take another survey of our cathedral during these years, apart from fightings and controversies. St. Paul's had been most closely connected with the continually growing prosperity of the city. The Lord Mayor was constantly worshipping there in state with his officers. On the 29th of October each year (the morrow of SS. Simon and Jude) he took his oath of office at the Court of Exchequer, dined in public, and, with the aldermen, proceeded from the church of St. Thomas Acons (where the[page 32] Mercers' Chapel now is) to the cathedral. There a requiem was said for Bishop William, as already described,3 then they went on to the tomb of Thomas Becket's parents, and the requiem was again said. This done they returned by Cheapside to the Church of St. Thomas Acons, where each man offered a penny. On All Saints' Day (three days later) they went to St. Paul's again for Vespers, and again at Christmas, on the Epiphany, and on Candlemas Day (Purification). On Whitsun Monday they met at St. Peter's, Cornhill, and on this occasion the City clergy all joined the procession, and again they assembled in the cathedral nave, while the Veni Creator Spiritus was sung antiphonally, and a chorister, robed as an angel, waved incense from the rood screen above.4 Next day the same ceremony was repeated, but this time it was "the common folk" who joined in the procession, which returned by Newgate, and finished at the Church of St. Michael le Querne.5 And once more they went through the ceremony, the "common folk of Essex" this time assisting. There could not be fuller proof of the sense of religious duty in civil and commercial life. The history of the City Guilds is full of the same interweaving of the life of the people with the duties of religion. There is an amusing incident recorded of one of these Pentecostal functions. On Whitsun Monday, 1382, John Sely, Alderman of Walbrook, wore a cloak without a lining. It ought to have been lined with green taffeta. There was a meeting of the Council about this, and they gave sentence that the mayor and aldermen should dine with the offender at his cost on the following Thursday, and that he should line his cloak. "And so it was done."

At one of these Whitsun festivals (it was in 1327) another procession was held, no doubt to the delight of many spectators. A roguish baker had a hole made in his table with a door to it, which could be opened and shut at pleasure. When his customers brought dough to be baked he had a confederate under the table who craftily withdrew great pieces. He and some other roguish bakers were tried at the Guildhall, and ordered to be set in the pillory, in Cheapside, with lumps[page 33] of dough round their necks, and there to remain till vespers at St. Paul's were ended.

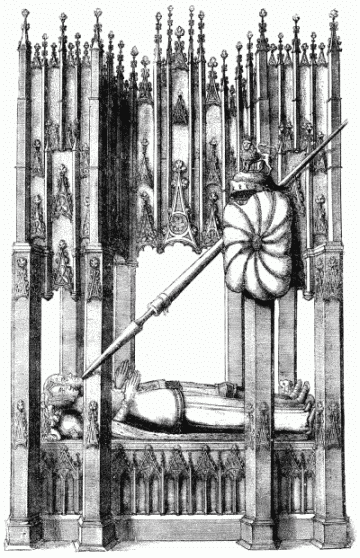

[plate 17]

MONUMENT OF

JOHN OF

GAUNT AND

BLANCHE OF

LANCASTER.

After W. Hollar.

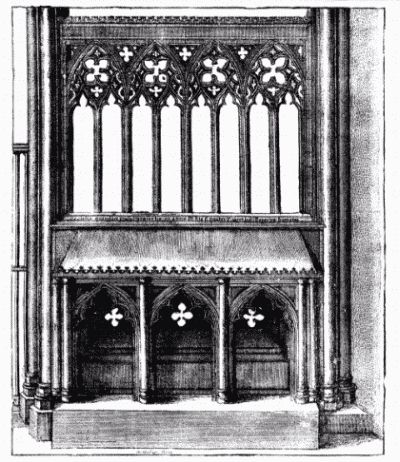

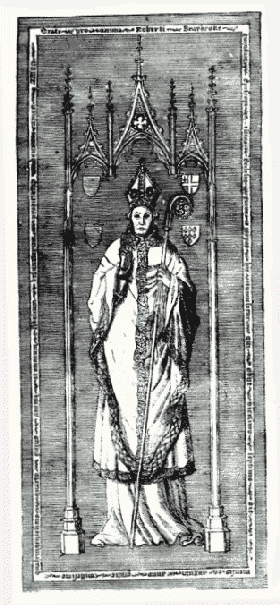

[plate 18]

THE

MONUMENT OF

BISHOP

ROGER

NIGER.

After W. Hollar.

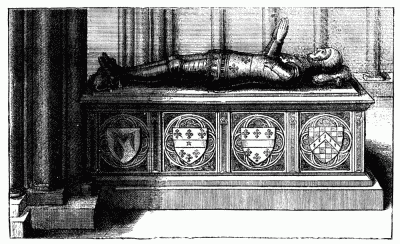

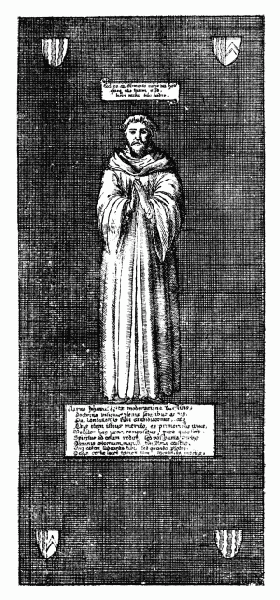

[plate 19]

THE

MONUMENT OF

SIR

JOHN

BEAUCHAMP, POPULARLY KNOWN AS

DUKE

HUMPHREY'S.

After W. Hollar.

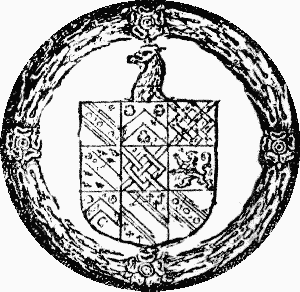

[plate 20a]

BRASS OF

BISHOP

BRAYBROOKE.

After W. Hollar.

[plate 20b]

BRASS OF

JOHN

MOLINS.

After W. Hollar.

[plate 20c]

BRASS OF

RALPH DE

HENGHAM.

After W. Hollar.

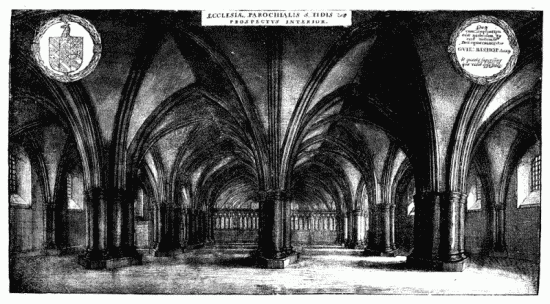

[plate 21]

ST.

FAITH'S

CHURCH IN THE

CRYPT OF

ST.

PAUL'S.

After W. Hollar.

[plate 21a]

ST.

FAITH'S

CHURCH IN THE

CRYPT OF

ST.

PAUL'S.

After W. Hollar. Detail of Arms.

[plate 21b]

ST.

FAITH'S

CHURCH IN THE

CRYPT OF

ST.

PAUL'S.

After W. Hollar. Detail of Inscription.

We return to the religious history, in which we left off with the name[page 33] of Wyclif. The Norman despotism of the Crown was crumbling away, so was the Latin despotism of the Church. On both sides there was evident change at hand, and Wiclif gave form to the new movement. He was born about 1324, educated at Oxford, where he won high distinction, not only by his learning, but by his holiness of life. The unparalleled ravages of the plague known as the "black death," not only in England but on the Continent, affected him so deeply that he was possessed by the absolute conviction that the wrath of God was upon the land for the sins of the nation at large, and especially of the Church, and he began his work as a preacher against the abuses. His first assault was upon the Mendicant Friars, whom he held up, as did his contemporary, Chaucer, to the scorn of the world. Then he passed on to the luxury in which some of the prelates were living, and to their overweening influence in the Councils of State. Edward III., after a reign of great splendour, had sunk into dotage. John of Gaunt had been striving for mastery against the Black Prince, but the latter was dying, July, 1376, and Gaunt was now supreme. He hated good William of Wykeham, who had possessed enormous influence with the old king, and he was bent generally on curbing the power of the higher clergy. At this juncture Wyclif was summoned to appear at St. Paul's to answer for certain opinions which he had uttered. It is not clear what these opinions were, further than that they were mainly against clerical powers and assumptions; questions of doctrine had not yet shaped themselves. He appeared before the tribunal, but not alone. Gaunt stood by his side. And here, for a while, the position of parties becomes somewhat complicated. Gaunt was at this moment very unpopular. The Black Prince was the favourite hero of the multitude, an unworthy one indeed, as Dean Kitchin has abundantly shown, but he had won great victories, and had been handsome and gracious in manners. He was now at the point of death, and Gaunt was believed to be aiming at the succession, to the exclusion of the Black Prince's son, and was associated in the popular mind with the King's mistress, Alice Ferrers, as taking every sort of mean and wicked advantage of the old man's dotage.[page 34] Added to this the Londoners were on the side of their Bishop (Courtenay) in defence, as they held, of the rights of the City. So on the day of Wyclif's appearance the cathedral and streets surrounding it were crowded, to such an extent indeed that Wyclif had much trouble in getting through, and when Gaunt was seen, accompanied by his large body of retainers, a wild tumult ensued; the mob attacked Gaunt's noble mansion, the Savoy Palace, and had not Courtenay intervened, would have burnt it down. The Black Prince's widow was at her palace at Kennington, with her son, the future Richard II., and her great influence was able to pacify the rioters.

Soon came an overwhelming change. The succession of the Black Prince's son was secured, and then public opinion was directed to the other question, Wyclif's denunciation of the Papal abuses. Relieved from Gaunt's partisanship, he sprang at once into unbounded popularity. His learning, his piety of life, were fully recognised, and the Londoners were now on his side. He had preached at the very beginning of the new reign that a great amount of treasure, in the hands of the Pope's agent, ought not to pass out of England. Archbishop Sudbury summoned him not to St. Paul's, but to Lambeth. But the favour with which he was now regarded was so manifest that he was allowed to depart from the assembly a free man, only with an injunction to keep silence "lest he should mislead the ignorant." He went back to Lutterworth, where he occupied himself in preaching and translating the Bible. He died in 1384. A wonderful impetus was, however, given to the spread of his opinions by the schism in the Papacy which was filling Europe with horrified amazement.

From that time till the accession of the Tudors, two subjects are prominent in English history: the spread of Lollardism, i.e., the Wycliffite doctrines, and the Wars of the Roses. Both topics have some place in the history of Old St. Paul's.

Richard II. on his accession came in great pomp hither, and never again alive. But his body was shown in the cathedral by his victorious successor, Henry IV., who had a few days before buried his father, John of Gaunt, there, who died at Ely House, Holborn, February 3rd, 1399, and whose tomb was one of the finest in the cathedral, as sumptuous as those of his father, Edward III., at Westminster, and his son, Henry [page 35] IV., at Canterbury.

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the youngest son of Henry IV., was appointed guardian of his infant nephew, Henry VI., on his father's death; but partly though the intrigues and squabbles of the royal family, partly by his own mismanagement, he lost the confidence of the nation. His wife, Jacqueline, had been persuaded by a sorcerer that her husband would be king, and she joined him in acts of witchcraft in order to bring this about. She was condemned (October, 1441) to do penance by walking three successive days in a white sheet and carrying a lighted taper, starting each day from St. Paul's and visiting certain churches. Her husband, says the chronicler Grafton, "took all patiently and said little." Still retaining some power in the Council, he lived until 1447, when he died and was buried at St. Albans. He was an unprincipled man, but a generous patron of letters and a persecutor of Lollards; and hence, in after years, he got the name of "the good Duke Humphrey," which was hardly a greater delusion than that which afterwards identified the tomb of Sir John Beauchamp in St. Paul's as Duke Humphrey's. But the strange error was accepted, and the aisle in which the said tomb lay was commonly known as "Duke Humphrey's Walk," and it was a favourite resort of insolvent debtors and beggars, who loitered about it dinnerless and in hope of alms. And thus arose the phrase of "Dining with Duke Humphrey," i.e., going without; a phrase, it will be seen, founded on a strange blunder. The real grave is on the south side of the shrine of St. Alban's.

Richard, Duke of York, swore fealty in most express terms to Henry VI. at St. Paul's in March, 1452. He had been suspected of aiming at the crown. But the government grew so unpopular, partly through the disasters in France, partly through the King's incapacity, that York levied an army and demanded "reformation of the Government." And on May 23rd, 1455, was fought the battle of St. Albans, the first of twelve pitched battles, the first blood spilt in a fierce contest which lasted for thirty years, and almost destroyed the ancient nobility of England. York himself was killed at Wakefield, December 23rd, 1460. On the following 3rd of March his son was proclaimed King Edward IV. in London, and on the 29th (Palm Sunday) he defeated Henry's Queen Margaret at Towton, the bloodiest battle ever fought on English[page 36] ground. A complicated struggle followed, during which there was much changing of sides. Once King Henry, who had been imprisoned in the Tower, was brought out by the Earl of Warwick, who had changed sides, and conducted to St. Paul's in state. But the Londoners showed that they had no sympathy; they were on the Yorkist side in the interest of strong government. Hall the chronicler makes an amusing remark on Warwick's parading of King Henry in the streets. "It no more moved the Londoners," he says, "than the fire painted on the wall warmed the old woman." That is worthy of Sam Weller. In May, 1470, Henry died in the Tower, and his corpse was exhibited in St. Paul's. It was alleged that as it lay there blood flowed from the nose as Richard Crookback entered, witnessing that he was the murderer. Richard afterwards came again to offer his devotions after the death of his brother, Edward IV., and all the while he was planning the murder of his young nephews.

Arthur, Prince of Wales, son of Henry VII., married Catharine of Aragon in St. Paul's, November 14th, 1501. He died five months later, at the age of 15. The chroniclers are profuse in their descriptions of the decorations of the cathedral and city on that occasion. The body of Henry VII. lay in state at St. Paul's before it was buried in Westminster Abbey.

This brings us to a new epoch altogether in our history. The stirring events now to be noted do not so much concern the material fabric of the cathedral as in the past, but they were of the most momentous interest, and St. Paul's took more part in them than did any other cathedral.

[page 37]

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:15:35 GMT