St Pauls, Index

CHAPTER VI.

THE CLERGY AND THE SERVICES.

St. Paul's a Cathedral of the "Old Foundation"—The Dean—The Canons—The Prebends—Residentiaries—Treasurer—Chancellor—Archdeacons—Minor Canons—Chantries—Obits—Music in Old St. Paul's—Tallis—Redford—Byrd—Morley—Dramatic Performances—The Boy Bishop—The Gift of the Buck and Doe.

We have recorded the building of the Cathedral and some of the principal national events of which it was the scene. But it is also necessary, if our conception of its history is to aim at completeness, to consider the character of its services, of its officers, of its everyday life.

We speak of St. Paul's as "a Cathedral of the Old Foundation," and of Canterbury and Winchester as of "the New Foundation." What is the difference? The two last named, along with seven others, had monasteries attached to them. Of such monasteries the Bishop was the Abbot, and the cathedral was immediately ruled by his subordinate, who was the Prior. Other monasteries also had Priors, namely, those which were attached to greater ones. Thus the "Alien" houses belonged to great monasteries at a distance, some of them even across the sea, in Normandy. These houses became very unpopular, as being colonies of foreigners whose interests were not those of England, and they were abolished in the reign of Henry V. When Henry VIII. went further and dissolved the monasteries altogether, it became needful to reconstitute those cathedrals which were administered by monks. St. Paul's not being such, remained on the old foundation; Winchester, of which the Bishop was Abbot of the Monastery of St. Swithun, was placed under a Dean and Canons, as was the great Monastery of Christchurch, Canterbury. The last Prior of Winchester became the first Dean. It is clear, therefore, that the Dean of Winchester stands on a somewhat different historical footing from the Dean of St. Paul's,[page 53] and it becomes necessary to say something about the latter.

The word Dean belongs to the ancient Roman law, Decanus, lit. one who has authority over ten, as a centurion was one who had authority over a hundred. The Deans seem originally to have been especially concerned with the management of funerals. Presently the name became adopted to Christian use, and was applied in monasteries to those who had charge of the discipline of every ten monks. When the Abbot was absent the senior Dean undertook the government; and thus it was that in cathedral churches which were monastic it gradually became the custom to have one who acted as Dean, and this system was gradually adopted in secular cathedrals, like St. Paul's. In monasteries, however, the Dean was so far subordinate to the Prior that he had charge of the music and ritual, while the Prior had a general superintendence.

The clergy of St. Paul's then were seculars. There were thirty of them, called Canons, as being entered on the list (κανών) of ecclesiastics serving the church. Each man was entitled to a portion of the income of the cathedral, and therefore was a "Prebendary," the name being derived from the daily rations (præbenda) served out to soldiers. There were thirty Canons or Prebendaries attached to St. Paul's, and these with the Bishop and Dean formed the Great Chapter. To them in theory belonged the right of electing the Bishop; but it was only theory, as it is still. The real nominator was the Pope or the King, whichever happened at the crisis to be in the ascendant.

In early days the Bishop was the ruling power inside the cathedral. At its first foundation, as we have seen, it was the Bishops who exerted themselves to raise the money for the building. But as time went on the Bishops, finding their hands full of affairs of state, stood aside in great measure, retired to their pleasant home at Fulham, and left to the Dean greater power. And thus it was that, as we have already told, Dean Ralph de Diceto built the Deanery. And thus gradually the Dean became practical ruler of the cathedral—the Bishop had no voice in affairs of the Chapter, except on appeal. And it is a curious fact that the Canons attempted to exclude the Dean from the managing body, as having no Prebend. He could expel from the choir, and punish the contumacious, but they contended that he had no power[page 54] to touch the revenues. It was because of this that Bishop Sudbury (1370), in order to prevent the scandal of the Dean being excluded when the Chapter were discussing business, attached a prebendal stall to the Deanery, and thereby enabled him to preside, without possibility of cavil, at all meetings of the Chapter.

As the Canons, or at any rate many of them, had other churches, they had each his deputy, who said the service in the Cathedral. Each Prebendary had his own manor, and there were other manors which belonged to the common stock, and supplied the means of carrying on the services and paying the humbler officials. The Canons, it will be remembered, were secular, not monks; but they had a common "College," with a refectory, kitchen, brewhouse, bakehouse, and mill. Archdeacon Hale computed that the manors comprised in all about 24,000 acres, three-eighths of which were managed by the cathedral body, and the rest let to tenants, who had protecting rights of their own. In addition to these were the estates attached to the Deanery.

But with the changes which Time is always bringing, it came to pass that some of the Canons, who held other benefices (and the number increased as the years went on), preferred to live on their prebendal manors, or in their parishes; to follow, in short, the Bishop's example of non-attendance at the cathedral. And thus the services devolved on a few men who stayed on and were styled Residentiaries. These clerics not only had their keep at the common College, which increased in comfort and luxury, but also came in for large incomes from oblations, obits, and other privileges. At first it seemed irksome to be tied down to residence, but as time went on this became a privilege eagerly sought after; and thus grew up, what continues still, a chapter within the chapter, and the management of the cathedral fell into the hands of the Residentiaries.

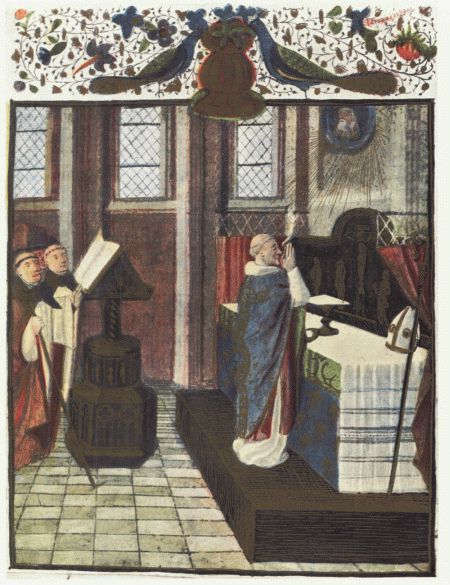

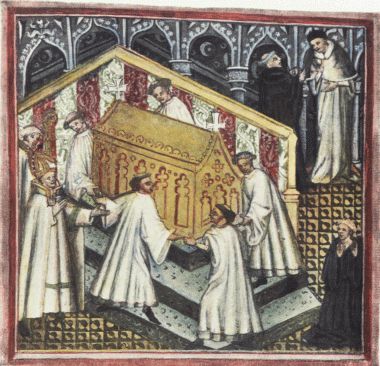

[plate 22]

A PONTIFICAL

MASS.

'Ad te levavi animam meam.'

From a Missal of the Fifteenth Century. British Museum, 19897.

The Treasurer was a canon of very great importance; the tithes of four churches came to him. He was entrusted with the duty of providing the lighting of the cathedral, and had charge of the relics, the books, the sacred vessels, crosses, curtains, and palls. The Sacrist had to superintend the tolling of the bells, to see that the church was opened at the appointed times, that it was kept clean, and that reverence was maintained at times of service. Under him were four[page 55] Vergers (wand-bearers), who enforced the Sacrist's rules, and took care that bad characters were not harboured in the church, and that burden-bearers were kept out. We have seen that these duties fell largely into abeyance at certain times. Every Michaelmas Day the Verger appeared before the Dean to give up his wand, and to receive it back if his character was satisfactory. The Verger was bound to be a bachelor, because, said the statute, "having a wife is a troublesome and disturbing affair, and husbands are apt to study the wishes of their wives or their mistresses, and no man can serve two masters."

The Chancellor kept charge of the correspondence of the Chapter, and also superintended the schools belonging to the cathedral.

The Archdeacons of London, Middlesex, and Colchester had their own stalls in the cathedral, but had no voice in the Chapter.

The Minor Canons, twelve in number, formed a separate college, founded in the time of Richard II. They were, of course, under the authority of the cathedral, though they had independent estates of their own.

The Scriptorium of St. Paul's was an important department, and was well managed. Much of the work produced in it perished in the fire; but there are some of its manuscripts still happily preserved, notably the Majora Statuta of the cathedral, in the Library there, and a magnificent folio of Diceto's History, now in Lambeth Library.

Incidental notice has been taken in the preceding pages of Chantries in St. Paul's, but we have to speak more fully of these, for they formed a very large source of income, especially to the Residentiary Canons. These Chantries were founded for saying masses for the souls of the departed, even to the end of the world. St. Paul's was almost beyond measure rich in them. The oldest was founded in the reign of Henry II., after which time they multiplied so fast that it would be impossible to enumerate them all here. There is a return of them (quoted at length by Dugdale), which was made by order of King Edward VI. Take the description of the second of them as he gives it. "The next was ordained by Richard, surnamed Nigell [Fitzneal], Bishop of London in King Richard I.'s time, who having built two altars in this cathedral, the one dedicated to St. Thomas the Martyr, and the other to St. Dionis, assigned eight marks yearly rent, to[page 56] be received out of the church of Cestreheart, for the maintaining of two priests celebrating every day thereat; viz., one for the good estate of the King of England and Bishop of London for the time being; as also for all the congregation of this church, and the faithful parishioners belonging thereto, and the other for the souls of the Kings of England and Bishops of London, and all the faithful deceased: which grant was confirmed by the Chapter." This is a fair specimen; they go on page after page in Dugdale's folio. William de Sanctæ Mariæ ecclesia (he was Dean 1241-1243) leaves 120 marks for bread and beer yearly to a priest who shall celebrate for his soul and for the souls of his predecessors, successors, parents, and benefactors. Sometimes special altars are named at which the Mass is to be said, "St. Chad, St. Nicholas, St. Ethelbert the King, St. Radegund, St. James, the twelve Apostles, St. John the Evangelist, St. John Baptist, St. Erkenwald, St. Sylvester, St. Michael, St. Katharine." I take them as they come in the successive testaments. The following passage is worth quoting:—"In 19 Ed. II. Roger de Waltham, a Canon of this church, enfeoft the Dean and Chapter of certain messuages and shops lying within the city of London, for the support of two priests to pray perpetually for his soul, and for the souls of his parents and benefactors, within the chapel of St. John the Baptist in the south part of this cathedral; as also for the soul of Antony Beck, Patriarch of Jerusalem, and Bishop of Durham. And further directed that out of the revenue of these messuages, &c., there should be a yearly allowance to the said Dean and Chapter, to keep solemn processions in this church on the several days of the invention and exaltation of the Holy Cross, as also of St. John Baptist; wearing their copes at those times in such sort as they used on all the great festivals; and likewise out of his high devotion to the service of God, and that it should be the more venerably performed therein, he gave divers costly vestments thereto, some whereof were set with precious stones, expressly directing that in all masses wherein himself by particular name was to be commended, as also at his anniversary, and in those festivals of the Holy Cross, St. John Baptist, and St. Laurence the Deacon, they should be used. And, moreover, out of his abundant piety he founded a certain Oratory on the south side of the Choir in this cathedral, towards the upper end thereof, to the honour of God,[page 57] our Lady, St. Laurence, and All Saints, and adorned it with the images of our blessed Saviour, St. John Baptist, St. Laurence, and St. Mary Magdalene; so likewise with the pictures of the celestial Hierarchy, the joys of the blessed Virgin, and others, both in the roof about the altar, and other places within and without; in which Oratory the chantry before mentioned was placed, and the said anniversary to be kept. And, lastly, in the south wall, opposite to the said Oratory, erected a glorious tabernacle, which contained the image of the said blessed Virgin, sitting as it were in childbed; as also of our Saviour, in swaddling clothes, lying between the ox and the ass, and St. Joseph at her feet; above which was another image of her, standing with the child in her arms. And on the beam, thwarting from the upper end of the Oratory to the before-specified childbed, placed the crowned images of our Saviour and his mother sitting in one tabernacle; as also the images of St. Katharine and St. Margaret, virgins and martyrs; neither was there any part of the said Oratory, or roof thereof, but he caused it to be beautified with comely pictures and images, to the end that the memory of our blessed Saviour and His saints, especially of the glorious Virgin, His mother, might be always the more famous: in which Oratory he designed that his sepulture should be."

[plate 23]

JOHN

FISHER,

BISHOP OF

ROCHESTER.

After Holbein.

British Museum.

[plate 24]

ST.

MATTHEW.

View of a Mediæval Scriptorium.

From a MS. of a Book of Prayers. 15th Century. British Museum, Slo. 2468.

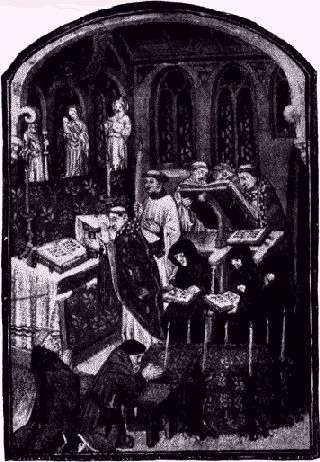

[plate 25]

A

REQUIEM

MASS.

From a MS. of a Book of Prayers, 15th Century.

British Museum, Slo. 2468.

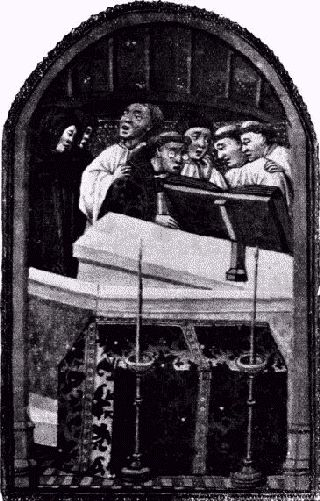

[plate 26]

SINGING THE

PLACEBO.

From a MS. of the Hours of the Virgin, &c. Fifteenth Century.

British Museum, Harl. 2971.

[plate 27]

SEALS OF THE

DEAN AND

CHAPTER.

From Casts in the Library of St. Paul's Cathedral.

[plate 28]

ORGAN AND

TRUMPETS.

From a Collection of Miniatures from Choral Service Books. Fourteenth Century.

British Museum, 29902.

Bishop Richard of Gravesend (d. at Fulham, 1306) made his will at his Manor House of Haringay, in 1302. It is written with his own hand, and the opening words are: "Imprimis, Tibi, o pie Redemptor, et potens Salvator animarum, Domine Jesu Christe, animam meam commendo; Tibi etiam, o summe Sacerdos et vere Pontifex animarum, commendo universam plebem Londonensis civitatis et diocæsis; obsecrans te, per medicinam vulnerum tuorum, qui in cruce pependisti, ut mihi et ipsis, concessa perfecta venia peccatorum, concedas nos ad tuam misericordiam pervenire, et frui beatitudine, tuis electis perenniter repromissâ." After which he goes on to direct that he shall be buried close to his predecessor, Henry de Sandwiche, whom he calls his special benefactor, and that the marble covering his grave shall not rise higher than the pavement; that out of his personal estate, consisting of books, household goods, corn and cattle, which together is valued at 2000 marks, 140l. shall be given to the poor, 100 marks to the new fabric of the cathedral, and that lands of the value of 10l. a year shall be[page 58] bought for the founding of a chantry here for his soul, and for the keeping of his anniversary.

In the Inventory of his goods we have interesting information about values: wheat is reckoned at 4s. the quarter, peas at 2s. 6d., and oats at 2s. Bulls are worth 7s. 4d. each, kine 6s., fat muttons 1s., ewes 8d., capons 2d., cocks and hens 1d. His nephew, Stephen, who succeeded him thirteen years later, allows only 100 marks for the expenses of his funeral, quoting St. Augustine that funeral parade may be a certain comfort to the living, but is of no advantage to the dead. He disposes of 140l. to the poor tenants on his manors. Bishop Michael Northburgh (d. 1362) left the rents of certain houses which he had built at Fulham for a chantry priest, who was to be appointed by the Bishop of London. He also desired to be buried on the same day he died, with his face exposed to view, outside the west door of the cathedral. His endowment of the chantry being judged to be insufficient, one of the nominated chantry priests gave a further endowment for it. This Bishop Northburgh left 2000l. for the completion of the house of the Carthusians (Charter House) in co-operation with Sir Walter Manny. He also left 1000 marks to be put into a chest in the Cathedral Treasury, out of which any poor layman might, for a sufficient pledge, borrow 10l., the Dean and principal Canons 20l. upon the like pledge; the Bishop 40l.; other noblemen or citizens 20l. for the term of a year. If at the year's end the money was not repaid, the preacher at Paul's Cross was to notify the fact, and to announce that the pledge would be sold within fourteen days if it were not redeemed, and any surplus from the sale would be handed to the borrower, or his executors. If there were no executors then the money was to go back to the chest, and be spent for the health of his soul. There were three keys to the chest, one was kept by the Dean, another by the oldest Canon-resident, and the third by a Warden appointed by the Chapter.

One keeps on finding benefactions of this sort. In 1370 one John Hiltoft's executors handed over some money which the Chapter employed in repairing some ruined houses; but they took care to establish a chantry of one chaplain to celebrate Divine service daily in St. Dunstan's Chapel for the soul of the said John.

We have already made mention of the chantry which Henry IV.[page 59] founded to the memory of his father and mother. Bishop Braybrooke on that occasion gave a piece of ground, part of his palace, 36 feet by 19 feet, for the habitation of the priests attached to this chantry. And King Henry, we are told, "gave to the Dean and Chapter, and their successors, for ever, divers messuages and lands, lying within the City of London, for the anniversary of the said John, Duke of Lancaster, his father, on the 4th day of February, and of Blanch, his mother, on the 12th day of September yearly in this church, with Placebo and Dirige, nine Antiphons, nine Psalms, and nine Lessons, in the exequies of either of them; as also Mass of Requiem, with note, on the morrow to be performed at the high altar for ever; and moreover to distribute unto the said Dean and Chapter these several sums, viz., to the Dean, as often as he shall be present, three shillings and fourpence; to the principal canons, twenty pence (to the sum of 16s. 8d.); to the petty canons, ten shillings; to the chaplains, twenty shillings; to the vicars, four shillings and eightpence; to the choristers, two shillings and sixpence; to the vergers, twelvepence; to the bell-ringers, fourpence; to the keeper of the lamps about the tomb of the said duke and duchess, at each of their said anniversaries, sixpence; to the Mayor of London for the time being, in respect of his presence at the said anniversaries, three shillings and fourpence; to the Bishop of London, for the rent of the house where the said chantry priests did reside, ten shillings; and for to find eight great tapers to burn about that tomb on the day of the said anniversaries, at the exequies, and mass on the morrow, and likewise at the processions, masses, and vespers on every great festival, and upon Sundays at the procession, mass, and second vespers for ever. And lastly, to provide for those priests belonging to that chapel on the north part of the said tomb, a certain chalice, missal, and portvoise [Breviary] according to the Ordinale Sarum; as also vestments, bread, wine, wax, and glasses, and other ornaments and necessaries for the same, and repairs of their mansion." A few years later another chantry was founded at the same altar for the soul of Henry IV. himself.

As years went on, the provision for all these Chantries being found inadequate to maintain them, some were united together, and thus, at their dissolution in the first year of Edward VI., it was found that there were only thirty-five, to which belonged fifty-four[page 60] priests.

In addition to the Chantries were the Obits held by the Dean and Canons, particular anniversaries of deaths. They varied in value according to the donors' endowment from 4l. to 10s. Dugdale gives a long list of them.

This cathedral was wonderfully rich in plate and jewels, so much so that, as Dugdale says, the very inventory would fill a volume. To take only one illustration: King John of France when he was brought here by the Black Prince "gave an oblation of twelve nobles at the shrine of St. Erkenwald, the same at that of the Annunciation, twenty-six floren nobles at the Crucifix by the north door, four basins of gold at the high altar; and, at the hearing of Mass, after the Offertory, gave to the Dean then officiating, five floren nobles, which the said Dean and John Lyllington (the weekly petty canon), his assistant, had. All which being performed, he gave, moreover, in the chapter-house, fifty floren nobles to be distributed amongst the officers of the church."

With regard to the character of the services before the Reformation, we have but few data to go upon. In 1414 Bishop Richard Clifford, with the consent of the Dean and Chapter, ordained that from the first day of December following, the use of Sarum should be observed. Up to that time there had been a special "Usus Sancti Pauli."

There was an organ in the church, or rather, to use the old phrase, a "pair of organs," for the instrument had a plural name like "a pair of bellows." Organs were in use in the church at any rate in the fourth century, and were introduced into England by Archbishop Theodore. In old times there was no official organist; the duty was taken by the master of the choristers or one of the gentlemen of the choir. In churches of the regular foundation a monk played.

English Church music, in its proper sense, began with the Reformation. In the Roman Church, the great genius of Palestrina had produced nothing less than a revolution as regards the ancient Plain Song; and with the English Liturgy we associate the honoured names of Tallis, Merbecke, Byrd, Farrant in the early days, and a splendid list of successors right down to our time, wherein is still no falling off. Tallis is supposed by Rimbault to have been a pupil of Mulliner, the organist of St. Paul's, but there is no evidence to support[page 61] this. It must be confessed that his service in the Dorian mode, which heads the collection in Boyce's Cathedral Music, and which is indeed the first harmonised setting of the Canticles ever composed for the English Liturgy, is very dull, but his harmony of the Litany and of the Versicles after the Creed, has never been equalled for beauty. His Canon tune, to which we sing Ken's Evening Hymn, is also unsurpassed, and his anthem, "If ye love Me," is one of wonderful sweetness and devout feeling. John Redford was his contemporary, and was organist of St. Paul's, 1530-1540. His anthem, "Rejoice in the Lord," is as impressive and stately as Tallis's that I have just named. It is frequently sung at St. Paul's still. William Byrd was senior chorister of St. Paul's in 1554. I hold his service in D minor to be the finest which had as yet been set to the Reformed Liturgy—the Nicene Creed in particular is of marvellous beauty. Tallis had not attempted "expression" in his setting of the Canticles. The meaning seems to breathe all through Byrd's harmonies. I did not know until I read Sir George Grove's article upon him, that Byrd secretly remained a Roman Catholic, but I long ago made up my mind, on my own judgment, that his most pathetic anthem, "Bow thine ear," was a wail over the iconoclasm in St. Paul's. He died in extreme old age in 1623. Morley was another organist of St. Paul's, the author of a fine setting of the Burial Service. Paul Hentzner, who visited St. Paul's in 1598, says in his Itinerary, "It has a very fine organ, which at evensong, accompanied with other instruments, makes excellent music."

Concerning the dramatic performances which went on in the cathedral at certain times, there is nothing peculiar to St. Paul's that I know of to mention. These performances were originally intended for instruction, pictorial representations of scenes from the Bible and Church History, but often degenerating into coarse buffoonery and horseplay. The "Boy Bishop" was for many generations an established institution. One ceremony there was, peculiar to St. Paul's, namely, "The Offering of a Buck and Doe." Sir William le Baud in 1328 made a yearly grant to the Dean and Canons of a doe to be presented on the Feast of the Conversion of St. Paul, and of a fat buck to be offered at the midsummer commemoration of the same Apostle.

These were to be offered at the high altar by Sir William and his[page 62] descendants, and afterwards to be distributed among the Canons resident. This gift was in acknowledgment of a grant which they had made him of twenty-two acres of land adjoining his park in Essex. There was a grand ceremonial on each occasion, the Canons wore their best vestments and garlands of flowers, and there was a procession round the church, with the horns of the buck carried on a spear, and a great noise of horn-blowers. Camden describes it all, as an eye-witness. This festivity came to an end in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

[plate 29]

BISHOP AND

CANONS IN THE

CHURCH OF

ST.

GREGORY-BY-ST.

PAUL.

From a MS. of Lydgate's Life of St. Edmund.

British Museum, Harl. 2278.

Our illustration, showing the costume of the clergy of St. Paul's, is taken from a MS. of Lydgate's Life of St. Edmund, written in the fifteenth century, and decorated with many miniatures. It represents the coffin of St. Edmund temporarily deposited in the church of St. Gregory-by-St. Paul's (having been brought up from Bury for safety during an incursion of the Danes), and an attempt by the Bishop and Canons to secure so precious a relic for the cathedral. Here is Lydgate's metrical version of the story, telling how the attempt was frustrated by the Saint himself.

He cam to Londene toward eve late,

At whos komyng blynde men kauhte syht.

And whan he was entred Crepylgate

They that were lame be grace they goon upryht,

Thouhtful peeple were maad glad and lyht;

And ther a woman contrauct al hir lyve,

Crying for helpe, was maad hool as blyve.

Thre yeer the martir heeld ther resydence,

Tyl Ayllewyn be revelacion

Took off the Bysshop upon a day licence

To leede Kyng Edmund ageyn to Bury town.

But by a maner symulacion

The bysshop granteth, and under that gan werche

Hym to translate into Powlys cherche;

Upon a day took with hym clerkis thre,

Entreth the cherche off seyn Gregory,

In purpose fully, yiff it wolde be,[page 63]

To karye the martir fro thenys prevyly.

But whan the bysshop was therto most besy

With the body to Poulis forto gon,

Yt stood as fyx as a gret hill off ston.

Multitude ther myhte noon avayle,

Al be they dyde ther fforce and besy peyne;

For but in ydel they spent ther travayle.

The peple lefte, the bysshop gan dysdeyne:

Drauht off corde nor off no myhty chayne

Halp lyte or nouht—this myracle is no fable—

For lik a mount it stood ylyche stable.

Wherupon the bysshop gan mervaylle,

Fully diffraudyd off his entencion.

And whan ther power and fforce gan to faylle,

Ayllewyn kam neer with humble affeccion,

Meekly knelyng sayde his orysoun:

The kyng requeryng lowly for Crystes sake

His owyn contre he sholde not forsake.

With this praier Ayllewyn aroos,

Gan ley to hand: fond no resistence,

Took the chest wher the kyng lay cloos,

Leffte hym up withoute violence.

The bysshop thanne with dreed and reverence

Conveyed hym forth with processioun,

Till he was passid the subarbis off the toun.

[page 64]

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:15:35 GMT