St Pauls, Index

CHAPTER VII.

FROM THE ACCESSION OF THE STUARTS TILL THE DESTRUCTION OF THE CATHEDRAL.

Fresh signs of Decay and Neglect—Visit of James I.—Bishop Earle's Account of Paul's Walk—Laud's Letter to the Citizens—Sir Paul Pindar's Munificence—The Rebellion—Monuments of the Stuart Period: Carey, Donne, Stokesley, Ravis, King, Vandyke—Attempts at Restoration: Inigo Jones, Wren—The Great Fire: Accounts of Pepys and Evelyn, Eye-witnesses—Sancroft's desire to Restore the Old Cathedral found quite impossible—Final Decision to Build a New One.

We saw how, in the reign of Elizabeth, a great calamity befell the cathedral in the falling of the spire, and through this the great injury to the roof, and further how the Queen, as well as the citizens, endeavoured to repair the damage. The spire was not rebuilt, but the roof was renewed. But fifty years later it was discovered that the work had been fraudulently done, and the church was falling to pieces. James I. came with much ceremony, in consequence of the importunities which he received, to survey the cathedral,1 and in consequence of what he saw he appointed a commission to consider what steps should be taken. At the head of it was the Lord Mayor, and amongst the names is that of "Inigo Jones, Esquire, Surveyor to his Majesty's Works." This remarkable man, though he was born in the parish of St. Bartholomew the Less, Smithfield, was educated in Italy, through the generosity of Herbert, third Earl of Pembroke.

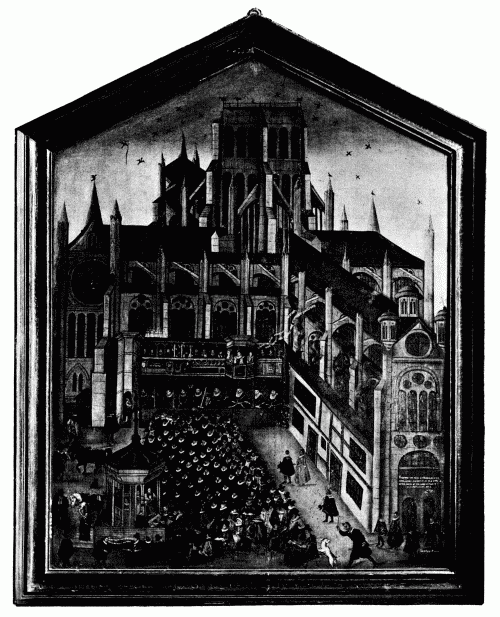

[plate 30]

MONUMENT OF

DR.

DONNE.

After W. Hollar.

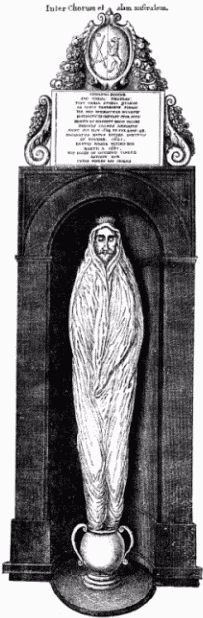

[plate 30a]

MONUMENT OF

DR.

DONNE.

Inscription

After W. Hollar.

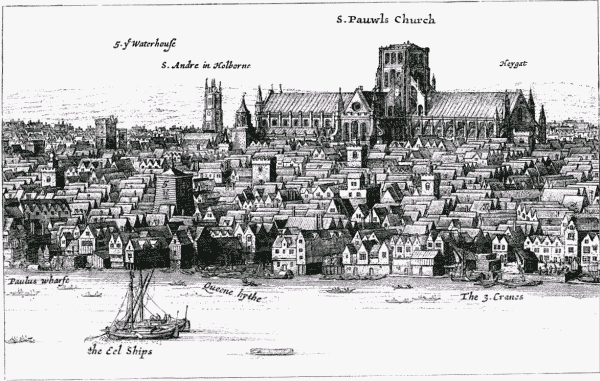

[plate 31]

PREACHING AT

PAUL'S

CROSS BEFORE

JAMES

I.

From a Picture by H. Farley. Collection of the Society of Antiquaries.

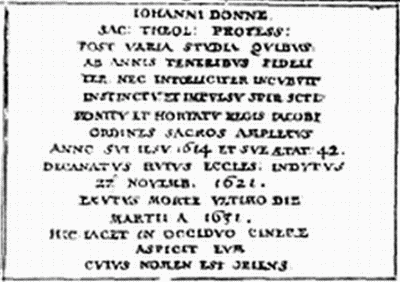

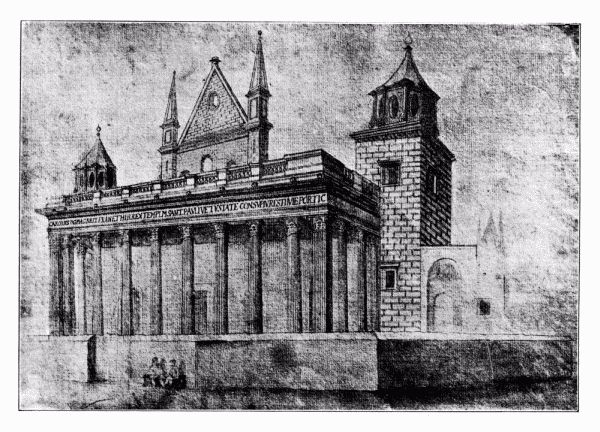

[plate 32]

OLD

ST.

PAUL'S FROM THE

THAMES.

After W. Hollar..

[plate 33]

WEST

FRONT AFTER THE

FIRE.

From a Drawing in the Library of St. Paul's Cathedral.

He now took the lead in the restoration of St. Paul's. It must[page 65] be acknowledged that after the first outburst of zeal following the fire of 1561, St. Paul's was much neglected for many long years. The authorities were lukewarm, the services were dead and unattractive, and all manner of irreverence was seen there daily. Bishop Earle's Microcosmography (1628) often gets quoted, but his description of "Paule's Walke" ought to find place here. I take it from a contemporary MS. copy. Paul's Walk was the whole nave of the cathedral:—"Paule's Walke is the lande's epitomy, or you may call it, the lesser Ile [Aisle] of Greate Brittayne. It is more than this, the whole woorlde's map, which you may here discerne in its perfect motion, justling and turning. It is an heape of stones and men, with a vast confusion of languages, and were the steeple not sanctified, nothing liker Babell. The noyse of it is like that of bees, an humming buzze mixed with walking tongues, and feet. It is a kind of still rore, or loude whisper. It is the greate exchange of all discourse, and noe business whatsoever but it is here stirring and on foote. It is the Synode of all pates politicke, jointed and layed together in most serious postures; and they are not halfe soe busy at the Parliament. It is the anticke of tayles to tayles, and backes to backes, and for vizzards you neede goe noe further than faces. Tis the market of young lecturers, which you may cheapen at all rates and sizes. It is the generall mint of famous lyes, which are here (like the legendes of Popery) first coyned, and stamped in the church. All inventions are emptied here, and not few pockettes. The best signe of a temple in it, is that it is the thieves' sanctuary, whoe rob here more safely in a crowde than in a wildernesse, whilst every searcher is a bush to hide them in. It is the other expence of a day after playes and the taverne ... and men have still some othes left to swear here.... The visitants are all men without exception, but the principall inhabitants are stale knights and captains out of servis, men with long rapiers and breeches, who after all turne merchant here, and trafficke for news. Some make it a preface to dinner and travell for a stomache, but thriftier men make it their ordinary, and boarde here very cheape. Of all such places it is least troubled with hobgoblins, for if a ghost would walk here he could not." Of "the singing men" he draws a most unfavourable picture, accuses them of drunkenness and shameful looseness of life; says that they are earnest in evil deeds and[page 66] that their work in the cathedral is their recreation. Bishop Pilkington also speaks of the profanity and worldliness of the daily frequenters. The carrying merchandise into the building seems to have been the custom in many of the cathedrals, and so it is not wonderful that the building went to ruin. The Bishop of London, Laud, sent round exhortations to the City Companies to contribute to the restoration. Here is his letter to the Barber Surgeons, dated January 30th, 1632:—

"To the right worshipful my very worthy friends the Master Wardens and Assistants of the Company of Barber Surgeons, London, these:

"Salus in Christo. After my very hearty commendations you cannot but take notice of his Majesty's most honest and pious intention for the repair of the decay of Saint Paul's Church here in London, being the mother church of this City and Diocese, and the great Cathedral of this Kingdom. A great dishonour it is, not only to this City, but to the whole state to see that ancient and goodly pile of building so decayed as it is, but it will be a far greater if care should not be taken to prevent the fall of it into ruin. And it would be no less disgrace to religion, happily established in this kingdom, if it should have so little power over the minds of men as not to prevail with them to keep those eminent places of God's service in due and decent repair, which their forefathers built in times, by their own confession, not so full of the knowledge of God's truth as this present age is. I am not ignorant how many worthy works have been done of late in and about this City towards the building and repairing of churches, which makes me hope that every man's purse will open to this great and necessary work (according to God's blessing upon him), so much tending to the service of God and the honour of this nation. The general body of this City have done very worthily in their bounty already, also the Lord Mayor, Aldermen and Sheriffs severally, for their own persons. These are, therefore, according to their examples, heartily to pray and desire you, the Master Warden and other assistants of the worthy Company of Barber Surgeons to contribute out of your public stock to the work aforesaid, what you out of your charity and devotion shall think fit, and to pay the sum resolved on by you into the Chamber of London at or before our Lady Day next, praying you that I may receive by any servant of your Company a[page 67] note what the sum is which you resolve to give. And for this charity of yours, whatever it shall prove to be, I shall not only give you hearty thanks, but be as ready to serve you, and every of you, as you are to serve God and His Church. So, not doubting of your love and forwarding to this great work, I leave you to the grace of God, and shall so rest,

"Your very loving Friend,

"GUL:

LONDON."

The Court considered this letter on the 9th of April following, and agreed to pay £10 down, and the same sum each year for the next nine years.

We must not omit one munificent donor who came forward now: Sir Paul Pindar, who had made a large fortune as a Turkey merchant, and had been sent by King James as Ambassador to Constantinople, gave over £10,000 to the restoration of the cathedral. He died in 1650, and his beautifully picturesque house remained in Bishopsgate Street (it had been turned, like Crosby Hall, into a tavern) until 1890, when it was pulled down. Some of the most striking portions of its architecture are preserved in the Kensington Museum.

That the alterations and additions of Inigo Jones, under King James, were altogether incongruous with the old building everybody will admit. But there are excuses to be made. He knew very little about Gothic architecture. The only example now remaining of his attempts in this style is the Chapel of Lincoln's Inn. St. Katharine Cree in the City has been attributed to him, but with little probability. And if he had essayed to work in Gothic at St. Paul's, it would not have been in accordance with precedent. Nearly all our great cathedrals display endless varieties of style, because it was the universal practice of our forefathers to work in the style current in their own time. We rejoice to see Norman and Perpendicular under one roof, though they represent periods 400 years apart. In the case before us Gothic architecture had died out for the time being. Not only our Reformers, who did not require aisles for processions nor rich choirs, but the Jesuits also, who had sprung suddenly into mighty power on the Continent, repudiated mediæval art, and strove to adapt the classical reaction in Europe to their own tenets. Nearly all the Jesuit churches abroad are classical.

It was, no doubt, fortunate that Inigo Jones confined his work at St.[page 68] Paul's to some very poor additions to the transepts, and to a portico, very magnificent in its way, at the west end. He would have destroyed, doubtless, much of the noble nave in time; but his work was abruptly brought to an end by the outbreak of the Civil War. The work had languished for some years, under the continuance of causes which I have already adduced. But Laud, as Bishop of London, had displayed most praiseworthy zeal, and King Charles had supported him generously. When the troubles began, the funds ceased. In 1640 there had been contributions amounting to £10,000. In 1641 they fell to less than £2000; in 1643 to £15. In 1642 Paul's Cross had been pulled down, and in the following March Parliament seized on the revenues of the cathedral.

With the Rebellion the history of the cathedral may be said to be a blank. It would have been troublesome and expensive to pull it down, so it was left to decay; the revenues were seized for military uses, and the sacred vessels sold. There is a doubtful tradition that Cromwell tried to sell the building to the Jews for a stately synagogue. Inigo Jones's portico was let out for shops, the nave was turned into cavalry barracks. An order, quoted by Sir Henry Ellis, of which there is a copy in the British Museum, came out in 1651 prohibiting the soldiers from playing at ninepins from nine p.m. till six a.m., as the noise disturbs the residents in the neighbourhood, and they are also forbidden to disturb the peaceable passers by. At the Church of St. Gregory by St. Paul, towards the latter part of Cromwell's life, it is said that the liturgy of the Church was regularly used, through the influence of his daughter, Elizabeth Claypole, and not only so, but that he used sometimes to attend it under the same auspices.

Once more before the catastrophe let us pause and see what monuments had been erected in the Cathedral since the Stuarts mounted the throne. Dean VALENTINE CAREY was also Bishop of Exeter, d. 1626, a High Churchman, He "imprudently commended the soul of a dead person to the mercies of God, which he was forced to retract." There was a brass to him with mitre and his arms, but no figure.

Then we come to a monument which has a very great and unique interest, that of Dr. John Donne, who was Dean from 1621 to 1631. It is hardly needful to say that his life is the first in the beautiful set of[page 69] biographies by his friend, Izaak Walton. But it seems only right to quote Walton's account of this monument. The Dean knew that he was dying, and his friends expressed their desire to know his wishes. He sent for a carver to make for him in wood the figure of an urn, giving him directions for the compass and height of it, and to bring with it a board, of the just height of his body. "These being got, then without delay a choice painter was got to be in readiness to draw his picture, which was taken as followeth:—Several charcoal fires being first made in his large study, he brought with him into that place his winding-sheet in his hand, and, having put off all his clothes, had this sheet put on him, and so tied with knots at his head and feet, and his hands so placed as dead bodies are usually fitted to be shrouded and put into their coffin or grave. Upon this urn he thus stood, with his eyes shut, and with so much of the sheet turned aside as might show his lean, pale, and death-like face, which was purposely turned towards the East, from whence he expected the second coming of his and our Saviour Jesus." In this posture he was drawn at his just height; and when the picture was fully finished, he caused it to be set by his bedside, where it continued, and became his hourly object till his death, and was then given to his dearest friend and executor, Dr. Henry King, then chief Residentiary of St. Paul's, who caused him to be thus carved in one entire piece of white marble, as it now stands in that church; and, by Dr. Donne's own appointment, these words were affixed to it as an epitaph:—

JOHANNES

DONNE

Sac. Theol. Profess.

Post varia studia, quibus ab annis

Tenerrimis fideliter, nec infeliciter

incubuit;

Instinctu et impulsu Spiritus Sancti, monitu

et hortatu

Regis Jacobi, ordines sacros amplexus

Anno sui Jesu, MDCXIV. et suæ ætatis XLII

Decanatu hujus ecclesiæ indutus,

XXVII. Novembris, MDCXXI.

Exutus morte ultimo die Martii MDCXXXI.

Hic, licet in occiduo cinere, aspicit eum

Cujus nomen est oriens.

The unique interest attaching to this monument is in the fact that [page 70] it was saved from the ruins of the old cathedral and now adorns the wall of the south choir aisle.

There are three more Bishops of this later period.

JOHN STOKESLEY (1530-1539) distinguished himself by his zeal in burning Bibles, and using all his influence on the side of Henry VIII. on the divorce, by his burning of heretics, and by his desire to burn Latimer. Froude tells the whole story with vivid pen. Stokesley was buried in St. George's Chapel in the N.E. corner of the cathedral. He was the last of the pre-Reformation bishops buried in St. Paul's.

THOMAS RAVIS (1607-1610) was buried in the N. Aisle, with simply a plain grave-stone telling that he was born at Malden in Surrey, educated at Westminster and Oxford, Dean of Christ Church and Bishop of Gloucester. But a most vigorous epitaph of him was written by his friend and successor at Christ Church, Bishop Corbet, namely, a poem in which extolling his virtues and his piety, he declares that it is better to keep silence over his grave, considering the profanation which is daily going on in the cathedral, the "hardy ruffians, bankrupts, vicious youths," who daily go up and down Paul's Walk, swearing, cheating, and slandering. And he sums up thus:—

"And wisely do thy grievèd friends forbear

Bubbles and alabaster boys to rear

On thy religious dust, for men did know

Thy life, which such illusions cannot show."

JOHN KING (1611-1621) was the last bishop buried in Old St. Paul's.

Some of the greatest English painters are buried in the present cathedral. In Old St. Paul's rested the bones of Van Dyck, who may almost be called the founder of English portrait painting, though he was a foreigner by birth, and only an adopted Englishman. He was born in Antwerp in 1599, became a pupil of Rubens, and, by general consent, surpassed him in portrait painting. In this branch of art he is probably unrivalled. He took up his residence in England in 1632, and was knighted by Charles I. He died at a house which that King had given him at Blackfriars, December 9th,[page 71] 1641, and was buried close by John of Gaunt.

We must not omit mention of John Tomkins, Organist of the Cathedral. He died in 1638. His epitaph says that he was the most celebrated organist of his time. He succeeded Orlando Gibbons at King's College, Cambridge, in 1606, and came to St. Paul's in 1619. His compositions, though good, are not numerous, but he is said to have been a wonderful executant.

But we must now approach the final scenes of Old St. Paul's. At the Restoration, Sheldon was made Bishop of London, and two years later, on his translation to Canterbury, was succeeded by Humphrey Henchman, a highly respectable man, who owed his elevation to his loyalty to the Stuarts during the Commonwealth. He took no part in public affairs, but was a liberal contributor to the funds of the cathedral. The Dean, John Barwick, was a good musician, and restored the choir of the cathedral to decent and orderly condition. But it was soon found that the building was in an insecure, indeed dangerous condition, and it became a pressing duty to put it in safe order. Inigo Jones had died in 1652, and the Dean, Sancroft, who had succeeded Barwick in 1664, called on Dr. Christopher Wren to survey the cathedral and report upon it.

This famous man was the son of the Rector of East Knoyle, in Wilts, and was born in 1632. His father had some skill in architecture, for he put a new roof to his church, and he taught his son to draw, an art in which he displayed extraordinary skill and taste. He was sent to Westminster School, and, under the famous Busby, became a good scholar. Then he went to Wadham College, Oxford, the Master of which, Wilkins, aftewards (sic) Bishop of Chester, was a great master of science. Wren took advantage of his opportunities, and became so well known for his acquirements in mathematics and his successful experiments in natural science that he was elected to a Fellowship at All Souls'. A few years later he was appointed to the Professorship of Astronomy at Gresham College, and his brilliant reputation made his rooms a meeting-place of the men who subsequently founded the Royal Society. A fresh preferment, that to the Chair of Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, did not hinder him from pursuing a fresh line. His father, as we have said,[page 72] taught him to draw, his mathematical skill guided his judgment in construction, and these two acquirements turned him more and more towards architecture, though even now he was held second only to Newton as a philosopher. His first appearance as an architect was his acceptance of the post of Surveyor of King Charles II.'s public works. This was in 1661. He lost no time in starting in his new profession, for in 1663 he designed the chapel of Pembroke College, Cambridge, which his uncle Matthew gave, and the Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford. This, then, brings him down to the survey of St. Paul's above named. It was carefully made, and presented in May, 1666. How he designed to rebuild some portions which were decayed, to introduce more light, to cut off the corners of the cross and erect a central dome—all this boots not now to tell. The plans were drawn, and estimates were ordered on Monday, August 27th, 1666.

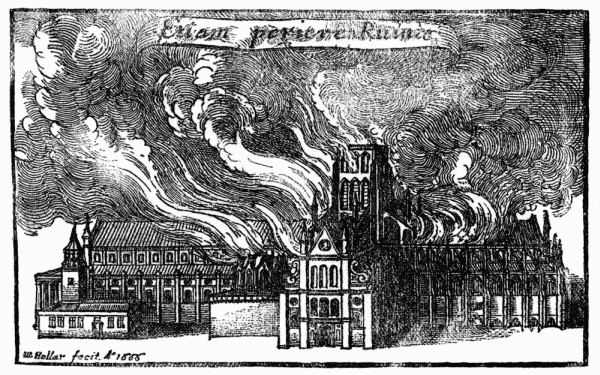

But before another week had passed an effectual end was put for many a day to all plans for the "repair of the cathedral." Pepys begins his diary of September 2nd with the following words:—"Lord's Day.—Some of our maids sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast to-day, Jane calls us up about three in the morning to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City; so I rose and slipped on my night-gown and went to her window, and thought it to be on the back of Mark Lane at the farthest." He thought this was far enough off and went to bed again. But next day he realises that it is all a terrible business, and so he goes on to tell how he walked about the streets and in some places burned his shoes; went on the river, where the hot fiery flakes pursued him; went to the King and gave advice and received instructions; met the Lord Mayor who seemed out of his senses. So he goes on with his well-known description until September 7th, when he was "Up by five o'clock, and blessed be God! find all well, and by water to Paul's Wharf. Walked thence and saw all the town burned, and a miserable sight of Paul's Church, with all the roof fallen, and the body of the choir fallen into St. Faith's; Paul's School also, Ludgate, and Fleet Street."

Evelyn's note of the disaster is written in a higher key. "September 3rd ... I went and saw the whole south part of the City burning from Cheapeside to the Thames, and all along Cornehill (for it[page 73] likewise kindl'd back against the wind as well as forward), Tower Streete, Fen-church Streete, Gracious Streete, and so along to Bainard's Castle, and was now taking hold of St. Paule's Church, to which the scaffolds contributed exceedingly. The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonish'd, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, they hardly stirr'd to quench it, so that there was nothing heard or seene but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures, without at all attempting to save even their goods—such a strange consternation there was upon them, so as it burned both in breadth and length, the churches, public halls, Exchange, hospitals, monuments, and ornaments, leaping after a prodigious manner from house to house and streete to streete, at greate distances one from the other; for the heate, with a long set of faire and warme weather, had even ignited the aire and prepar'd the materials to conceive the fire, which devoured after an incredible manner, houses, furniture, and everything. Here we saw the Thames cover'd with goods floating, all the barges and boates laden with what some had time and courage to save, as, on the other, the carts, &c., carrying out to the fields, which for many miles were strew'd with moveables of all sorts, and tents erecting to shelter both people and what goods they could get away. Oh, the miserable and calamitous spectacle, such as haply the world had not seene the like since the foundation of it, nor be outdone till the universal conflagration of it. All the skie was of a fiery aspect, like the top of a burning oven, and the light seene above forty miles round about for many nights. God grant mine eyes may never behold the like, who now saw above 10,000 houses all in one flame; the noise and crackling and thunder of the impetuous flames, the shreiking (sic) of women and children, the hurry of people, the fall of Towers, Houses, and Churches, was like an hideous storme, and the aire all about so hot and inflam'd that, at the last, one was not able to approach it, so that they were forc'd to stand still and let the flames burn on, which they did for neere two miles in length and one in bredth. The clowds also of smoke were dismall, and reach'd, upon computation, neer fifty-six miles in length. Thus I left it this afternoone burning, a resemblance of Sodom or the last day. It forcibly call'd to my mind that passage—non[page 74] enim hic habemus stabilem civitatem: the ruines resembling the picture of Troy—London was, but is no more! Thus I returned home.

"September 7th.—I went this morning on foote from White-hall as far as London Bridge, thro' the late Fleete-streete, Ludgate Hill, by St. Paules, Cheapeside, Exchange, Bishopsgate, Aldersgate, and on to Moorefields, thence thro' Cornehill, &c., with extraordinary difficulty, clambering over heaps of yet smoking rubbish, and frequently mistaking where I was....

"At my returne I was infinitely concern'd to find that goodly Church St. Paules now a sad ruine, and that beautifull portico (for structure comparable to any in Europe, as not long before repair'd by the late King) now rent in pieces, flakes of vast stone split asunder, and nothing now remaining intire but the inscription in the architrave, shewing by whom it was built, which had not one letter of it defac'd. It was astonishing to see what immense stones the heate had in a manner calcin'd, so that all the ornaments, columns, freezes, capitals, and projectures of massie Portland-stone flew off, even to the very roofe, where a sheet of lead covering a great space (no less than six akers by measure) was totally mealted; the ruines of the vaulted roofe falling broke into St. Faith's, which being fill'd with the magazines of bookes belonging to the Stationers, and carried thither for safety, they were all consum'd, burning for a weeke following. It is also observable that the lead over the altar at the East end was untouch'd, and among the divers monuments, the body of one Bishop remain'd intire. Thus lay in ashes that most venerable Church, one of the most antient pieces of early piety in the Christian world."

Sancroft, who was Dean at the time of the fire, and who afterwards became Archbishop, was anxious to restore the cathedral on the old lines. Henchman was Bishop, but he left the matter for the Dean to deal with, though he not only rebuilt the Bishop's Palace at his own expense but contributed munificently to the new building. Sancroft preached within the ruined building before the King on October 10th, 1667, from the text, "His compassions fail not," and the sermon is really eloquent. The congregation was gathered at the west end, which had been hastily fitted up. The east end was absolute ruin.

Wren had already declared that it was impossible to restore the old[page 75] building, and in the following April, Sancroft wrote to him that he had been right in so judging. "Our work at the west end," he wrote, "has fallen about our ears." Two pillars had come down with a crash, and the rest was so unsafe that men were afraid to go near, even to pull it down. He added, "You are so absolutely necessary to us that we can do nothing, resolve on nothing without you." This settled the question.

There is a little difficulty with regard to the drawing, preserved in the library of the cathedral, of the West Front after the Fire. Evelyn, as we have seen, seems to describe it as far more ruinous than the picture before us shows. Perhaps the artist filled up some of the details from his memory, for the drawing hardly looks so desolate a ruin as Evelyn implies. The gable of the nave roof is striking enough, and evidently exactly according to fact; and the tower of St. Gregory's preserves its external form, though it is inwardly consumed, as is the whole nave. I am inclined to judge that this is substantially the appearance of the porch after the west end had been fitted up for worship as Sancroft described. However, Wren had condemned the structure as unsafe, and the Dean had acquiesced, and the new cathedral was resolved upon.

There was delay, which was inevitable. Not only was the whole city paralysed with the awful extent of the ruin, but there were questions which had to be referred to Parliament, as to the method of raising the funds. Happily the whole voice of the people was of one accord in recognising that it was a paramount duty for the nation to build a splendid cathedral, worthy of England and of her capital city. It was not until November 1673 that the announcement was made of the determination of the King and his Parliament to rebuild St. Paul's. The history of that rebuilding belongs to New St. Paul's. The King wanted to employ a French architect, Claude Perrault, who had built the new front of the Louvre, but this was objected to. Then Denham, whose life may be read in Johnson's Poets, and who wrote one poem which may still be met with, Cooper's Hill, was appointed the King's Surveyor, with Wren for his "Coadjutor." Denham held the title to his death, but had nothing to do with the work. He died next year, and Wren then held unquestioned possession. His account of the old building, the principal features of which have been borrowed[page 76] in the foregoing paper, is given in his son's book entitled Parentalia. Our plan shows a change which Wren made as to the orientation. In all probability this arose out of his scrupulous care as to the nature of the foundation. The clearing away was most difficult. Parts had to be blown up with gunpowder. It is said that when he was giving instructions to the builders on clearing away the ruins, he called on a workman to bring a great flat stone, which he might use as a centre in marking out on the ground the circle of the dome. The man took out of the rubbish the first large stone that came to hand, which was a piece of gravestone, and, when it was laid down, it was found to have on it the single word "RESURGAM." He took this, and there was no superstition in such an idea, as a promise from God.

[plate 34]

OLD

ST.

PAUL'S IN

FLAMES.

Etiam periere ruinæ.

W. Hollar fecit. A° 1666.

[page 77]

And Last updated on: Thursday, 09-Jan-2025 14:15:35 GMT