MAPS

OF OLD LONDON

| I. | WYNGAERDE (IN THREE SECTIONS) |

| II. | AGAS |

| III. | SECTION OF AGAS |

| IV. | HOEFNAGEL |

| V. | NORDEN LONDON |

| VI. | NORDEN WESTMINSTER |

| VII. | FAITHORNE. |

| VIII. | OGILBY. |

| IX. | ROCQUE |

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1908

|

EDWARD STANFORD, Geographer to the King, 12, 13, and 14, Long Acre, London, W.C. |

EDITOR'S NOTE

An atlas of Old London maps, showing the growth of the City throughout successive centuries, is now issued for the first time. Up to a recent date the maps here represented had not been reproduced in any form, and the originals were beyond the reach of all but the few. The London Topographical Society has done admirable work in hunting out and publishing most of them; but these reproductions are, as nearly as possible, facsimiles of the originals as regards size, as well as everything else. It is not every one who can afford to belong to the society, or who wishes to handle the maps in large sheets. In the present form they are brought within such handy compass that they will form a useful reference-book even to those who already own the large-scale ones, and, to the many who do not, they will be invaluable.

The maps here given are the best examples of those extant, and are chosen as each being representative of a special period. All but one have appeared in the volumes of Sir Walter Besant's great and exhaustive "Survey of London," for which they were prepared, and the publishers believe that in offering them separately from the books in this handy form they are consulting the interests of a very large number of readers.

The exception above noted is the map known as Faithorne's, showing London as it was before the Great Fire; this is added for purposes of comparison with that of Ogilby, which shows London rebuilt afterwards. Besides the maps properly so called, there are some smaller views of parts of London, all of which are included in the Survey.

The atlas does not presume in any way to be exhaustive, but is representative of the different periods through which London passed, and shows most strikingly the development of the City.

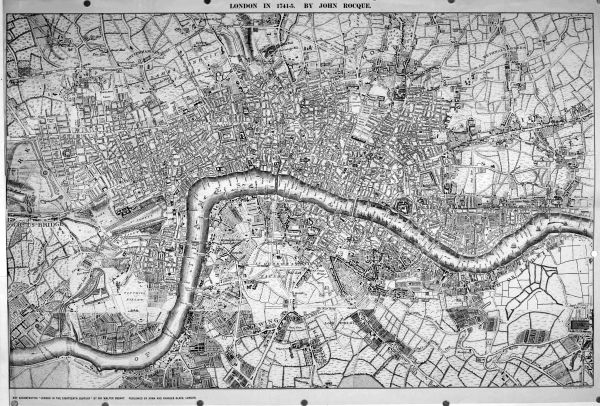

LONDON IN 1741-45

By JOHN ROCQUE

Description.—In some ways this map is the most interesting of the whole series, for it comes nearest to our own times, and yet by studying it we can infer the remarkable changes that have taken place within the memory of man. It is much more comprehensive than Ogilby's, including the whole of the outlying suburbs, and even going as far as Edgware and Tottenham, which are still no part even of Greater London.

Designer.—Very little is known about John Rocque. He was probably a native of France, but was residing in England about 1750. He engraved maps and a few views from his own designs.

Original.—The original is in twenty-four sheets, and is 13 feet in length and 6¾ feet in depth. It can be seen at the British Museum. That which is here presented is the central part of this, not reduced, but on the same scale. Its interest is greatly increased by the fact that the names are printed on the map, and are not given separately as in other instances. To facilitate this Rocque has marked the houses bordering streets in white, and only blocked them in black where they line market-gardens and other parts indicated by a light surface. The map is a model of care and comprehensive detail.

Detail.—Beginning in the lower left-hand corner, we have the Royal Hospital, with its neatly-laid-out grounds. Close to it the Westbourne, whose irregular line determined the boundaries of Chelsea, falls into the Thames; higher up its course is through the Five Fields, now one of the most wealthy and popular districts of London—namely, Belgravia. St. George's Hospital is already standing at Hyde Park Corner, and a fringe of houses lines the road to Knightsbridge. Westminster is still largely open in the west by Tothill Fields, scene of so many tournaments and jousts, and the curve of the river encloses innumerable market-gardens. In St. James's Park the stiff canal, memento of Dutch influence, has not yet been transformed into the more attractive ornamental water. Carlton House Terrace has not come into existence. Here Carlton House, which does not appear to be marked, was standing, and was occupied by Frederick, Prince of Wales, father of George III. North of this, with the omission of Regent Street, made in 1813-20, the streets are pretty much as we know them. It is beyond Oxford Street northward that the difference is striking. This district was only just being built upon, and the well-laid-out streets soon run off into open country. "Marybone" Gardens, a favourite tea-garden, and the church, and a few houses, form a little hamlet just connected with the other part of London by a single street, and further westward, north of Berkeley Square, are fields. In the midst of these is the "Yorkshire Stingo," the public-house from which the first omnibus in the Metropolis began to run in 1829. The Tyburn Gallows still had much work to do; it was fifty years later that the last execution took place here. Just within the Hyde Park is the gruesome record, "where soldiers are shot." If we follow Oxford Street eastward to Tottenham Court Road, we find that it is only connected with High Holborn by the curve through High and Broad Streets at St. Giles's. To the south is the star of Seven Dials, and all the district so completely altered by the cutting through of Charing Cross Road, and then Shaftesbury Avenue in modern times. To the north, Montagu House occupies the site the British Museum was destined to fill; it was purchased by the Government in 1753, and pulled down about a hundred years later. Bedford House, the town residence of the Dukes of Bedford, stood until 1800. Behind, Lamb's Conduit Fields run up to Battle Bridge, where one of the early British battles was fought; this is now the site of King's Cross Station. Not far off Bagnigge Wells and Sadler's Wells are in the heyday of their prosperity. The Fleet or River of Wells may be traced passing through the former, but further south it is covered in, and does not appear in the open again until below Fleet Bridge, when it is ignominiously called Fleet Ditch.

Thames side is still fringed with "stairs to take water at" leading from the great houses on the margin, and there is as yet no embankment. Westminster and Blackfriars Bridges, however, afford easy access to the southern side. The labyrinth of the City is not seriously different from that of the present day except in the omission of Cannon Street. Bethlehem Hospital is still conspicuous, and the City wall has vanished strangely. What we now call Finsbury Square is marked as Upper Moorfields. We have to go far before we clear the houses to the east. Stepney and Bethnal Green are fairly thickly populated, and though surrounded by open ground, are connected by houses all the way from the City. But in the bend of the river by Wapping the chief area is occupied by market-gardens. Crossing over to the other side, we find the market-gardens very prominent; as London grows larger she thrusts her sources of supply further from her. The central ganglion of the Borough Road and its ray-like connections are marked out. At one end is the "King's Bench," which was close to the Marshalsea, associated with "Little Dorrit." The Marshalsea itself is not marked. Dickens was yet to come, and it was only through his writings that it gained a sentimental interest. A great part of the Borough is very marshy indeed, and we note frequent ponds. The "Dog and Duck," otherwise "St. George's Spaw," is almost surrounded by them.

To sum up in Sir Walter Besant's words:

"London, then, in the eighteenth century consisted first of the City, nearly the whole of which had been rebuilt after the Fire, only a small portion in the east and north containing the older buildings; a workmen's quarter at Whitechapel; a lawyer's quarter from Gray's Inn to the Temple, both inclusive; a quarter north of the Strand occupied by coffee-houses, taverns, theatres, a great market, and the people belonging to these places; an aristocratic quarter lying east of Hyde Park; and Westminster, with its Houses of Parliament, its Abbey, and the worst slums in the whole City. On the other side of the river, between London Bridge and St. George's, was a busy High Street with streets to right and left; the river bank was lined with houses from Paris Gardens to Rotherhithe; there were streets at the back of St. Thomas's and Guy's; Lambeth Marsh lay in open fields, and gardens intersected by sluggish streams and ditches; and Rotherhithe Marsh lay equally open in meadows and gardens, with ponds and ditches in the east....

"From any part of London it was possible to get into the country in a quarter of an hour. One realizes the rural surroundings of the City by considering that north of Gray's Inn was open country with fields; that Queen Square, Bloomsbury, had its north side left purposely open in order that the residents might enjoy the view of the Highgate and Hampstead Hills. On the south side of the river Camberwell was a leafy grove; Herne Hill was a park set with stately trees; Denmark Hill was a wooded wild; the hanging woods of Penge and Norwood were as lovely as those that one can now see at Cliveden or on the banks of the Wye" (London in the Eighteenth Century, pp. 77-79).